The Corbyn spy hoax and the cycle of fake news

Since about a year or so, we officially live in the age of fake news, In mid-February 2018, the British tabloid The Sun published an article in which Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was accused of having been involved in espionage activities in the 1980s. According to The Sun (and quickly endorsed by The Daily Mail), Czech archives and statements by a former Czech spy confirmed that Corbyn had repeatedly met Warsaw Pact intelligence agents and had been paid for his services. In a curious return to the days of Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Sun claimed the existence of secret Stasi files, the contents of which might reveal numerous names of British traitors whose real identities, alas, "we will never know for sure". But Corbyn? Yes, they were sure of him being a traitor to his country.

A highly effective campaign was waged on social media, marginalizing the voices supporting the tabloids and their stories.

The allegations were swiftly turned into truth by hostile politicians and opinion makers. The Defence Secretary stated that Corbyn had betrayed his country, and another Cabinet member compared Corbyn to the Cold War cause célèbre Kim Philby - here is Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy once again. In the overheated atmosphere of the Brexit debates in UK politics, heavy artillery is quickly and frequently used. Evidently, the issue went trending on social media and became headline news and a major commentary topic in the mass media as well.

#CorbynSmears

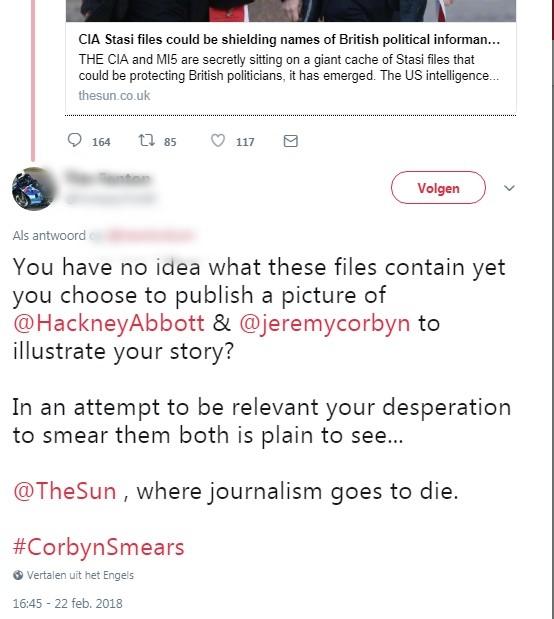

The allegations, however, were quickly debunked. Corbyn himself swiftly dismissed them as "a ridiculous smear" and ridiculed the tablois for "going a bit James Bond," probably as a sign of fear for the Labour leader whose popularity is on the rise. The real James Bonds - British intelligence officers - backed him up. There was no evidence of Corbyn performing espionage duties for the Czech secret services. On social media, hashtag activism started at once using #CorbynSmears as the thematic label for three large types of actions: direct discussion (as in Figure 1), boomerang statements pointing towards other fake news stories by these tabloids (as in Figure 2), and more broadly focused political essays on the role of media in society (as in Figure 3). A highly effective campaign was waged on social media this way, marginalizing the voices supporting the tabloids and their stories.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Battle hashtags such as #CorbynSmears went trending as well, for several days, and while the tabloids made desperate attempts to raise the "free press" flag and extend their line of revelations, they lost the day. When the facts and the backgrounds are on your side, fact checking (or better: fact reconstruction) is a devastating weapon in social media discussions. The three genres of activity shown here shaped three interlocking frames of action: (a) demanding factual evidence for claims in direct one-on-one interaction; (b) background checks disputing the overall credibility of the tabloids, and (c) pointing to broader motives of political power and influence behind such forms of media reporting. Taken together and deployed en masse, they were highly effective in silencing the opponents in the online debates. The Corbyn supporters had shown themselves to be a formidable social media force on previous occasions; they did so once more in the spy hoax case.

The Corbyn spy hoax shows us a thing or two about what we can call the contemporary cycle of (fake) news.

The mass media (who a few days earlier carried the story as headline news) turned against the spy issue - now identified as fake news - with unusual vehemence. The Independent printed a razor-sharp sarcastic commentary piece including a summary of other outrageous tabloid hoaxes about Corbyn. And BBC Daily Politics anchor Andrew Neil mercilessly pummeled a Cabinet Minister on the question of whether or not Corbyn had betrayed his country, concluding: “Surely the real scandal is not what Mr Corbyn has ..supposedly done but the outright lies and disinformation that you and fellow Tories are spreading - that’s the real scandal isn’t it?” The clip of this interview fragment went viral too, and in many ways functioned as a climax to the debate: if the BBC formulates the issue in such a categorical way - connecting "scandal", "lies" and "Tories" in one sentence - then that's it.

The cycle of fake news

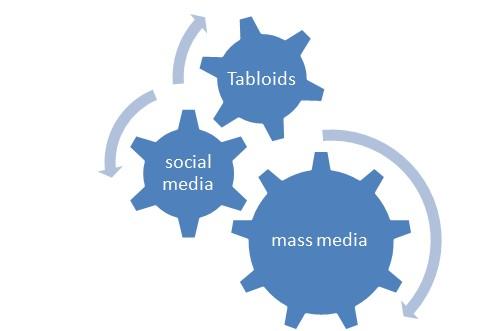

The Corbyn spy hoax of course taps into the highly complex issue of fake news - perhaps the most important new theme in media culture nowadays, certainly after the exposure of the impact of media such as Breitbart News on the election victory of Donald Trump. And in connecion to this issue, the Corbyn spy hoax shows us a thing or two about what we can call the contemporary cycle of (fake) news. In a graphic form, this cycle can be represented as such (Figure 4).

Figure 4: the cycle of (fake) news

Three wheels are constantly turning in a validation debate, in which the tabloids and the social media do most of the work, while the mass media perform a relatively passive, responsive but nevertheless decisive role. Debates about the validity of news items are hot and hectic in the first two media channels, and these validation debates are taken up by mass media at various stages of development. Thus, mass media very often make an item not just out of the facts of the case, but about the debates on the validity of these facts in other media channels.

Mass media very often make an item not just out of the "facts" of the case, but about the debates on the validity of these facts in other media channels.

What we observe here suggests a changed media environment - now called the hybrid media system - in which it would be wrong to see social media as just echo chambers for what was produced in more traditional media channels. They now must be placed alongside those more traditional channels, as echo chambers, surely, but also in two other capacities: as critical producers of news in the strict sense of the term; and as the critical producers of the criteria for "real" and "fake" news. This latter capacity is what makes their position in this new media environment inevitably controversial, but nonetheless of extreme importance for understanding the present structure and dynamics of the public sphere and public opinion - a key concept for defining democracy.