BiDil and race-based medicine: perspectives and stakeholders

The website of The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reports that African American adults aged 18-49 years old are two times as likely to die from heart disease than white adults. In this light it is not surprising that pharmaceutical companies identified African American adults with heart failure as a potentially profitable market for selling medication to. In this paper I will disentangle the emergence of the first race-based heart medication: BiDil.

BiDil: objectivity and the power of statistics

To provide a thorough understanding of the development of this controversial drug I will provide a short history of BiDil, followed by comments on the research design and ultimately this paper will shed light on the various perspectives and influences of different stakeholders. It is useful to look into this because it shows how a variety of interests and stakeholders can influence the seemingly objective and neutral process of knowledge production in medicine.

As Porter (1995) explains, the ideal of objectivity strives for the cancelling out of individuals and their biases by means of quantification and statistics. The randomized controlled trial (RCT) has become synonymous with this kind of objectivity and impersonality. An RCT tests the effectiveness of a medical intervention by randomly allocating test subjects into two groups: an intervention group and a control group receiving a placebo or the standard treatment. Ideally, this trial is blinded, which means that information about who is receiving which treatment is only revealed after completing the trial. Statistical analysis is then used to determine which medical intervention is most effective. As the gold standard, the RCT supposedly has no need for interpretation and judgement. Instead, we can rely on the numbers it produces. Evidence-based medicine prioritizes this kind of statistical evidence, ideally generated by RCTs. However, I will argue that whilst the researchers used RCTs to study the effectiveness of the race-based heart medication BiDil, this case shows that there are limits to the statistical approach.

A variety of stakeholders influenced and pushed the development of the drug into a particular direction and statistics were used in order to find a way to get the drug onto the market. Porter also emphasizes the social and political dimensions of quantification. Not only is quantification considered masculine and primarily white, the power of objectivity that is connected to numbers has the ability to create norms based on averages. I argue that the development of BiDil is also strongly connected to a social, economic and political context. If we take it at face value, by targeting the drug to African Americans the manufacturers seem to provide heart failure patients with a personalized medication that counters the predominantly white randomized controlled trial by solely enrolling black patients. However, the main reason to produce a heart medication that is primarily effective for black patients lies within the economic incentives and stakeholder interests. I will discuss this later in this paper.

Before I dive into a critique of the research methods and the different perspectives of the stakeholders I will first provide a history of how BiDil came to be. I will briefly summarize the history that is presented by Sankar and Kahn (2005) in the following sections.

A short history of BiDil

BiDil, the first heart medication that targeted a specific race, was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug administration (FDA) in 2005. It all started with the Vasodilator Heart Failure Trial (V-HeFT I). This was a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial that studied the effect of vasodilators (drugs that open or widen blood vessels) on the mortality of white and black men with heart failure. In the study that was published in 1986 they found that combining the two generic ingredients hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate (H-I) reduced the mortality rate. The researchers conducted a second trial in the late 1980s called V-HeFT II to study the effect of the angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor enalapril. ACE inhibitors lower blood pressure by relaxing veins and arteries in the body. V-HeFT II found that enalapril was even more effective than H-I in treating heart failure.

Jay Cohn, the lead cardiologist in the trials, decided to patent the H-I combination as a specific, fixed dose and for the purpose of treating heart failure. This fixed-dose pill received the name BiDil. It is important to keep in mind that at this stage the drug was not targeting a specific race. Together with the pharmaceutical company Medco he tried to get the approval of the FDA to market the new drug. In the late 1990’s, the FDA rejected BiDil, because the V-HeFT trials did not produce the statistically significant data needed to approve a new drug. The FDA recognized the positive effects of BiDil. However, the RCT was never designed to provide data for the approval of a new drug, but rather as a trial that tested a theory.

The birth of the first race-based medication

This is not where the history of BiDil ends. Cohn set his sights on getting BiDil on the market, but he needed a plan of action to achieve this. Together with another researcher of the V-HeFT trials, cardiologist Peter Carson, he re-examined the data and set out to find a statistical significance based on race. In 1999 Cohn and Carson published a retrospective study in the Journal of Cardiac Failure suggesting that H-I reduced the mortality rate of black patients with 4 percent (Carson et al., 1999).

One year later Cohn and Carson applied for a race-specific patent to use H-I to treat heart failure in African Americans. To get the approval from the FDA they had to perform a confirmatory trial in African Americans. NitroMed, the company that possessed the intellectual property rights at this point, raised a significant amount of funding and started the African American Heart Failure Trial (A-HeFT) with one thousand self-identified African Americans with heart failure. The trial found a 43 percent reduction in mortality rate and a 33 percent reduction in hospitalization. The FDA approved BiDil as a supplement to standard therapy for treating heart failure in self-identified black patients. A race-based heart medication was born.

Producing medical knowledge

During the process of getting BiDil approved some methods of producing medical knowledge were involved that I would like to comment on. First, it is difficult to base decisive conclusions on retrospective analysis of data and making new subgroups in a randomized controlled trial such as V-HeFT I. As Dorothy Roberts explains in her book 'Fatal invention: How science, politics, and big business re-create race in the twenty-first century' (Roberts, 2012) there was a numerical imbalance between the participants. In V-HeFT I only 49 black and 132 white patients received the H-I combination. It is hard to tell if a small subgroup in an RCT can produce a statistically significant difference or if any differences are due to chance.

In addition, Roberts points out that in a retrospective analysis the researchers cannot control for other factors (e.g. social economic factors and medical history) or confounds that might explain the difference between black and white patients. Bibbins-Domingo and Fernandez (2007) also argue this point, explaining how the exclusion of a broad patient population does not allow researchers to provide more complex explanations of the factors that may underlie a difference between patient groups. Furthermore, Roberts draws attention to the difficulties of applying results to other patients almost twenty years later, since treatment options for heart conditions have changed in the meantime.

BiDil de-prioritizes social, economic, political and environmental factors that influence health and illness.

There are also some issues with the A-HeFT trial that will slowly move us towards the interests of different stakeholders. As Sankar and Kahn point out, the only way of getting funding for the trial was “playing the race card” (Sankar & Kahn, 2005, p. 6). To get FDA approval they had to design a trial that would confirm the claim of race being an important biological aspect in the treatment of heart failure. The question was not whether H-I was an effective treatment, but the goal was to prove its efficacy in a way that guaranteed FDA approval. This was achieved by only enrolling black people. They were randomized into two groups: those who received BiDil along with their standard medication, and those who received the placebo along with the standard medication. To prove that BiDil worked more effectively in black patients they would have had to design a study that compared black patients with a non-black control group. It is possible that this would have proved that BiDil was effective for everybody regardless of race. This would put an FDA approval at risk. I argue that this is a form of design bias.

Bias and incentives

Stegenga (2018) defines design bias as “a bias built into the internal design of a research method” (p. 108). It was already well established that H-I was an effective treatment, so by selecting solely black patients the researchers designed the clinical trial in such a way that it improved their chances of verifying the claim that BiDil was effective in the treatment of black patients with heart failure. Although A-HeFT was an RCT, by selecting only black patients I argue that this can still be considered a form of design bias.

Furthermore, for NitroMed there was also a financial and legal incentive to design the study in this way. By not enrolling a more diverse and larger population the trial was less expensive. The race-specific patent also ensured that the intellectual property rights and its market monopoly was extended with thirteen years. Sankar and Kahn (2005) argue that these conflicts of interest influenced the research by biasing the results and by “allowing potential financial gain to distort the design and trajectory of research” (p. 7). This illustrates how the pharmaceutical industry is not a neutral partner in the development of a medication. All the effort that went into the development of BiDil was not particularly aimed at producing medical knowledge, but at creating a new and profitable market.

Race: genetic marker or socio-political construct?

Another aspect of the study that is important to mention is the use of self-identified race (a social and political construct) as a substitute for a biological or genetic marker. The use of race is a very controversial issue in medical and medicine knowledge production. As Brody and Hunt (2006) explain, genomic science has not succeeded in finding a genetic marker for the social and political construct of race. In fact, genomic science found that there is more genetic difference within one “racial” group than between different groups. Brody and Hunt argue that this does not mean that we should abandon race as a factor in medical research, because “whatever its biological basis (or lack of same), race remains a very important social construct, and as such, it has tremendous power to influence health and illness” (p. 557). Additionally, they point out that BiDil might cause a de-emphasis of research into nongenetic contributors (e.g. social and environmental factors) to illness and disease.

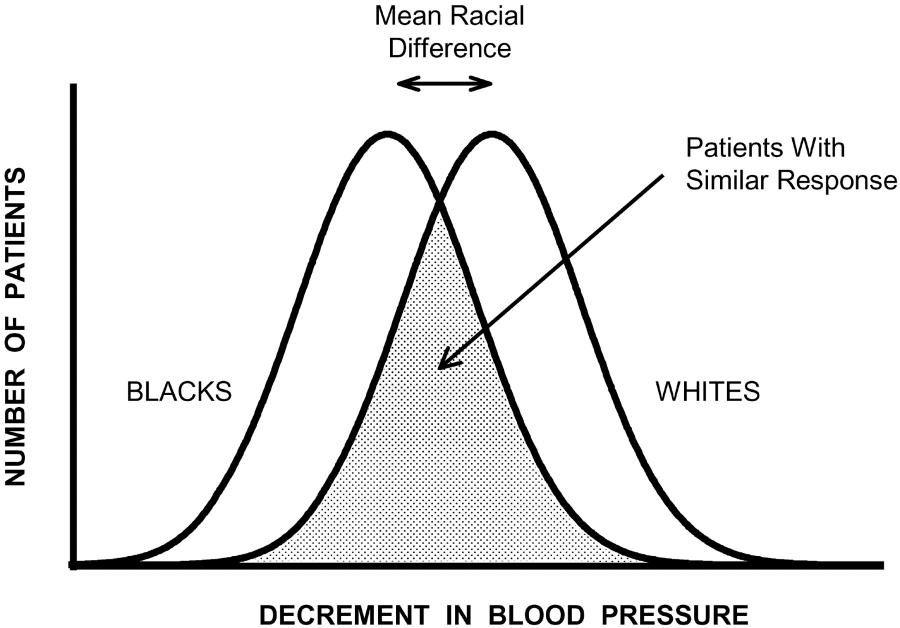

Sehgal (2004) contributes to this debate about using race as a proxy for other determinants of illness such as genetics or environmental factors. Sehgal analyzed fifteen clinical trials (most of them RCTs) to investigate whether there is a difference in drug response between white and black people. The analysis showed that many white and black people (between 80% to 95%) have similar responses to commonly used medications that treat high blood pressure. The analysis also shows that there is indeed a moderate statistically significant difference between the responses of black and white people. However, as we can see in the figure below, the majority of the patients had a similar response to the drugs (the grey or shaded area represents these similar responses). Not only does this example show how using race as a proxy is not sufficient to predict patient responses to drugs, it also shows how statistical information can be played with to find a favourable outcome.

Reduction in blood pressure among white and black people after administrating a drug to treat high blood pressure. Shaded area represents whites and blacks who have similar responses.

The quest for personalized medicine

The move towards race-based medicine fits historically into the emergence of personalized medicine in the early 2000s. As Miriam Solomon (2016) describes, the goal of personalized medicine, or precision medicine, is to discover new treatments through the use of genetic or other molecular information. Ultimately this should lead to better treatment of patient subgroups. This is something that evidence-based medicine was not able to provide, argues Solomon: “The best kind of evidence it can give is that patients with characteristics similar to the test population will have results statistically similar to the test population. It cannot predict the results for particular individuals.” (p. 290). BiDil seems to fit into the discourse of personalized medicine or at least as a stepping-stone to its goal, but ultimately it does not match the definition that Solomon provides. NitroMed marketed the drug as race-specific and personalized for African Americans, but population sample was not based on genetic or molecular information and instead the researchers used a social marker as a surrogate.

BiDil and African American interest groups

To market the drug and to recruit participants for the A-HeFT trial, NitroMed had help from multiple interest groups from the African American community such as the Association of Black Cardiologists, International Society on Hypertension in Blacks, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Congressional Black Caucus. Yu, Goering and Fullerton (2009) explain that although BiDil’s approval was criticized, advocates for African American health issues supported BiDil as “an important step toward reducing disparities in healthcare by creating medical therapies that are responsive to African American needs” (p. 57).

It is important to emphasize that the African American community was experiencing cognitive dissonance: on the one hand community leaders and health advocates saw in BiDil an opportunity to reduce health disparities, but on the other hand they rejected the concept of a race-specific drug since race is a social and political construct. For the community, supporting BiDil was a strategic move. BiDil recognized that research practices prioritized the white body and that black bodies were disproportionately affected by health problems such as heart failure. The significant media attention that was given to the first race-based drug helped in raising awareness to such disparities. Rather than completely rejecting BiDil, the African American community made the strategic decision to support the race-based drug with the hope of setting in motion a metamorphosis of future medical and pharmaceutical research.

Yu, Goering and Fullerton argue that in this light the support from the African American community should be seen in a context of fighting for justice and recognition. The approval of BiDil is then also a symbol of society’s interest in and commitment to improving African American health. However, as I mentioned before, BiDil de-prioritizes social, economic, political and environmental factors that influence health and illness.

Cardiologists' perspectives on race-based medications

To give more weight to the aforementioned concerns I will turn to the perspective of cardiologists. Callier et al. (2019) conducted eighty-one interviews with cardiologists in order to document their perspectives on prescribing a race-based drug. They focused specifically on the prescription of BiDil. More than half of the participants voiced their concern in prescribing a race-based medication and some of the cardiologists found this kind of medication to be inappropriate. An important concern is that by labelling a medication as a drug for African Americans, some cardiologists will not prescribe it to other populations that might also benefit from the drug.

Some cardiologists mention the design of the A-HeFT trial and point to the limitation of only enrolling African Americans. They argue that there are other medical factors that contribute to heart failure and that the design of the A-HeFT trial does not take this into account. Those who were in favour of prescribing BiDil mention that the trial confirms that the drug reduces the mortality rate in African Americans. Some cardiologists found that prescribing a race-based medication could be legitimized if the treatment provided positive outcomes. Additionally, they argue that the trial is an important step towards researching the needs of black patients, since most clinical trials primarily enrol white, male patients. These perspectives show that there is a need to address health disparities and diversity in medical research, but it also shows that we have to re-examine the process of knowledge production and the assumptions that underlie a race-based medication such as BiDil.

Even when an RCT is used to test drug efficacy there is no guarantee that the clinical trial design or the analysis is not biased by social, financial or political interests.

This tension between the need to address health disparities and the danger of misinterpreting the role of race in causing these disparities is also visible in how the media reported the coming into being of BiDil. In a news article published on 24 June 2005, NBC News highlights some of the concerns that experts voiced. The article points to the lack of biological meaning of the racial category used in the study, but it also acknowledges that rejecting the approval of BiDil would have raised questions, since the data showed a positive effect on patients with heart failure. The article additionally mentions the National Medical Association, which promotes the interest of African American physicians and patients. This association applauded the approval of BiDil, but also urged the researchers to conduct larger trials to establish whether BiDil would also be an effective treatment for other populations. The Guardian adds to this by pointing out the ethnic diversity within African Americans (Younge, 2005). This is what genomic research confirms: there is more genetic difference within a racial group than between them.

The end of BiDil?

The scepticism of these multiple stakeholders, including physicians and geneticists, did not help in promoting the new drug. As we can read in Race in a bottle (Kahn, 2012), BiDil failed to deliver the commercial success that NitroMed counted on. In January 2008 NitroMed decided to abandon the marketing activities of BiDil and in January 2009 NitroMed announced that the pharmaceutical company was acquired by Deerfield Capital, which had plans to continue the development of BiDil. In late 2011 Deerfield Capital sold the rights to BiDil to another pharmaceutical company: Arbor Pharmaceuticals. For a long time BiDil remained on the market with very little active marketing.

However, in 2019 Arbor Pharmaceuticals announced its partnership with former basketball player Shaquille O’Neal, who is the first spokesperson for the drug. A news article on Fierce Pharma, a website that covers news on the pharmaceutical industry, explains how marketing the drug to only healthcare providers was not enough to market BiDil. This is the reason why Arbor is starting a marketing campaign targeted at consumers and with a basketball celebrity as the face of the advertisements (Bulik, 2019). This shows how pharmaceutical companies are still trying to dominate a market that targets African American patients with heart failure, despite the various critical perspectives and profound scepticism.

Critical evaluation of knowledge production in health and medicine

In this paper I have shown how various interests and stakeholders such as community interest groups and pharmaceutical companies can influence knowledge production in medicine and the development of a new drug. A randomized controlled trial is often considered to be the gold standard of evidence-based medicine, but even when an RCT is used to test drug efficacy there is no guarantee that the clinical trial design or the analysis is not biased by social, financial or political interests. Our trust in statistical evidence can prevent us from looking behind those numbers and critically evaluate how knowledge is produced and examine whose interests are at stake. Knowledge can never be completely objective or neutral and the development of BiDil as the first race-based heart medication demonstrated this once again.

References

Experts wary over first race-based drug. (2005, June 24). MSNBC News.

Bibbins-Domingo, K., & Fernandez, A. (2007). BiDil for Heart Failure in Black Patients: Implications of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration Approval. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(1), 52.

Brody, H., & Hunt, L. M. (2006). BiDil: Assessing a Race-Based Pharmaceutical. The Annals of Family Medicine, 4(6), 556–560.

Bulik, B. S. (2019, April 4). Slam dunk? Arbor taps O’Neal for heart failure drug’s first consumer push. FiercePharma.

Callier, S. L., Cunningham, B. A., Powell, J., McDonald, M. A., & Royal, C. D. M. (2019). Cardiologists’ Perspectives on Race-Based Drug Labels and Prescribing Within the Context of Treating Heart Failure. Health Equity, 3(1), 246–253.

Carson, P., Ziesche, S., Johnson, G., & Cohn, J. N. (1999). Racial differences in response to therapy for heart failure: Analysis of the vasodilator-heart failure trials. Journal of Cardiac Failure, 5(3), 178–187.

Kahn, J. (2012). Race in a Bottle. Columbia University Press.

Porter, T. M. (1995). Trust in numbers. Princeton University Press.

Roberts, D. (2012). Fatal Invention: How Science, Politics, and Big Business Re-create Race in the Twenty-first Century. The New Press.

Sankar, P., & Kahn, J. (2005). BiDil: Race Medicine Or Race Marketing? Health Affairs, 24(Suppl1), W5-455.

Sehgal, A. R. (2004). Overlap Between Whites and Blacks in Response to Antihypertensive Drugs. Hypertension, 43(3), 566–572.

Solomon, M. (2016). On ways of knowing in medicine. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 188(4), 289–290.

Stegenga, J. (2018). Care and Cure: An Introduction to Philosophy of Medicine. University of Chicago Press.

Younge, G. (2005, June 16). Heart drug triggers race debate. The Guardian.

Yu, J., Goering, S., & Fullerton, S.M. (2009). Race-Based Medicine and Justice as Recognition: Exploring the Phenomenon of BiDil. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics, 18(1), 57–67.