“Hey Google, is buying your smart home speaker actually that smart?”

Smart home devices, like the Google Nest speaker, have transformed the way we live our daily lives and interact with our homes. With just one simple voice command, we can control the lighting in our house, and room temperatures, make phone calls, play music and even order our weekly groceries. This way, smart home devices have undoubtedly made our lives easier, but at what cost? The results of the latest Adobe’s State of Voice Assistants report (Southern, 2018) show 71 per cent of smart speaker owners use voice commands every day, and 44 per cent multiple times a day. As we become more reliant on such devices, we are also sharing more data about ourselves and our daily routines. How harmless are these voice interactions and how much privacy do we still have in our own home? Our home is a supposedly, safe and private space, or so we thought. For that reason, this paper aims to explore what privacy issues voice interactions with the Google Nest speaker raise for its users, what happens to the data collected and why we still choose to continue to use these speakers.

Background and operation of the Google Nest speaker

The Google Nest speaker is a smart home device that allows users to control various functions in their homes with just a voice command. The device is powered by Google Assistant, which is an AI-powered virtual assistant that can answer questions, make phone calls and perform various other tasks. To set up the Google Nest audio speaker, users are required to download the Google Home app, which serves as the central hub for managing and controlling various smart devices. Like every other app, before signing up one must consent to data processing under the terms of their privacy policies. Once the app is installed, users can connect the speaker to their Wi-Fi network, customize settings, activate voice match functions and interact with other smart devices in their home. This way, it becomes an integrated part of one’s smart home ecosystem. While the setup process may seem routine, it is during this moment that the Nest speaker gains its first intimate glimpse into one’s daily life, by gaining immediate access to personal information associated with a personal Google account, such as one’s name, email, IP and billing address, terms they search for and data of any other activity while using Google services.

Additionally, the Google Nest speaker has become increasingly controversial and faced several privacy scandals over the years, following reports of their data collection methods and accusations of spying on users (Williams, 2020). Following this, the company made changes to its privacy policy and now allows users to opt out of various functions. Nevertheless, concerns remain about the privacy implications of using the Google Nest speaker.

Privacy, the expository society and the age of surveillance capitalism

There are different ways in which privacy is understood. This paper looks at this concept through the lens of McCreary (2008), who defines privacy as a form of self-possession, custody of the facts of one’s life, from strings of digits to tastes and preferences. He argues that matters like health and finance are nobody's business but our own unless we decide otherwise. This version of privacy encompasses our desire to have control over all the information we possess and manage. However, the continued collection of our digital activities, such as Google voice searches, creates a sense of uncontrollable exposure to our personal information. Furthermore, to understand why Google tracks personal information, the concept of surveillance capitalism will be applied.

According to Zuboff (2019), surveillance capitalism can be understood as “a new economic order that claims human experience as free raw material for hidden commercial practices of extraction, prediction, and sales.” In other words, companies collect and use personal data and human experiences for commercial purposes and as described by Zuboff (2019), Google was the pioneer of surveillance capitalism in thought and practice. The company has been at the forefront of developing and implementing sophisticated methods for tracking and analyzing user behavior online. Its business model relies heavily on personalized ads, utilizing vast data collected across its products to create detailed user profiles, contributing to a transformative shift in capitalism, as highlighted by Zuboff, where surveillance and personal data extraction play a central commercial role. Understanding the implications of surveillance capitalism, especially in the context of Google's pioneering role, is essential as it reveals the ethical dilemmas surrounding personal privacy and the integrity of our digital interactions. It is therefore important to critically assess the balance between technological convenience and fundamental human rights in the surveillance society we live in today.

Finally, the theory of the expository society is examined. Harcourt (2015) has argued that we have entered a society in which we increasingly exhibit ourselves online and freely give away our most personal data. With the proliferation of social media platforms, people willingly share intimate details of their lives, often without fully grasping the consequences. In doing so, individuals make it easy to be watched, monitored and tracked. This willingness to share intimate aspects of our lives raises important questions about the future of our privacy.

Methods

When using Nest devices and services with a Google account, data will be processed as described in the Google privacy policy (Nest, n.d.). Therefore, the data for this analysis was obtained by examining the general privacy policy and support page of Google. The policy was accessed through the official Google website and collected data was analyzed by connecting the identified information to the aforementioned theory and concepts. Additionally, existing research was reviewed to provide further support for the arguments presented. Although Google's full privacy policy has been reviewed, this analysis focuses on the most relevant sections related to audio- and voice data. The research phase started on May 24th, 2023 and ended on June 1, 2023.

Privacy implications of the Google Nest speaker

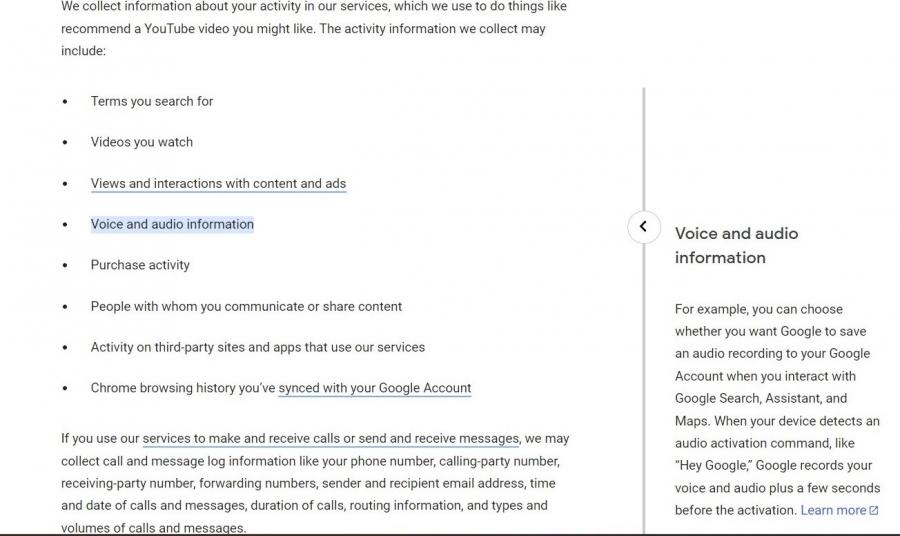

Figure 2: overview of the data Google collects

Unleashing the forbidden: eavesdropping and unintentional recordings

The privacy policy states that Google collects all activity information, including voice and audio information (figure 2). This means that users can choose whether Google saves audio recordings to their Google account when interacting with the Assistant; which is always the case with the Nest speaker. However, when taking a critical view of the privacy policy it states “Google records your voice and audio plus a few seconds before the activation” (Google, 2022). How is the speaker able to tell when someone is planning to use certain activation words? Technically, this means that the speaker is constantly listening in to catch certain commands, and once detected, it starts recording and capturing the user's voice and audio data. Thus, it can be argued that people are constantly “eavesdropped” and monitored by the Nest speaker in their private homes (Akinbi & Berry, 2020). This way, there exists a possibility of unintended activations. Google's privacy policy explains that sometimes the Google Assistant may be mistakenly activated when it misinterprets sounds or when you accidentally trigger it. Research (Manning, 2021) shows that smart speakers may be falsely triggered between 1.5 to 19 times per day. A later study observed about 0.95 misactivations per hour of audio or 1.43 misactivations per 10,000 words spoken. Thus, a device that is functioning correctly can record, save, and transmit audio that a user does not intend to direct to the device. This highlights the potential privacy implications and the need for users to be aware of the risks associated with having a smart speaker that is always eavesdropping in their homes.

Unveiling the secrets: harnessing data for voice technology advancements

Secondly, as written in their policy, personal data is also used to provide, maintain and improve Google's services (Google, 2022).

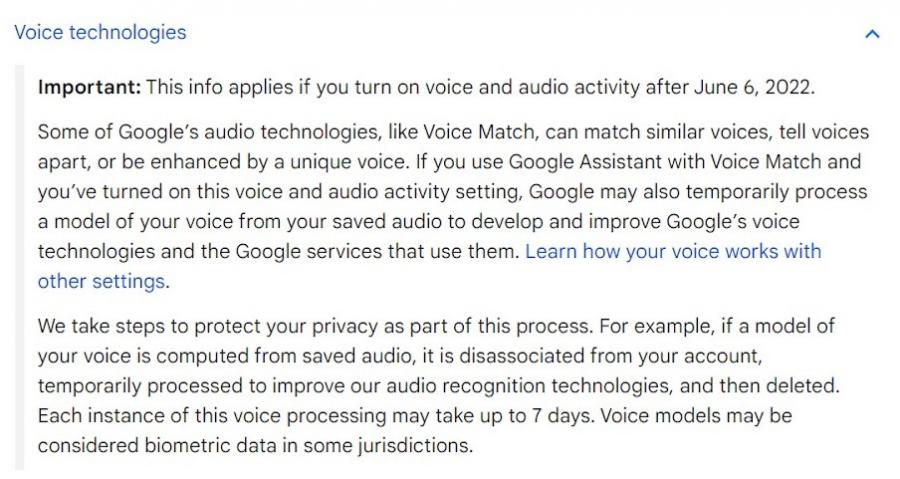

Figure 3: how audio recordings are used

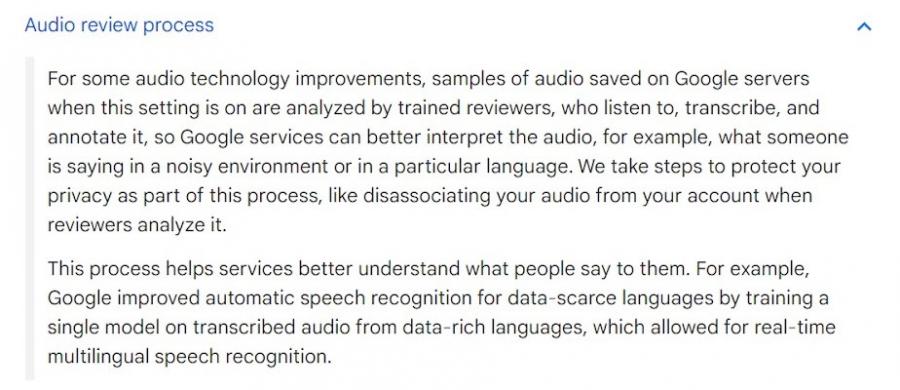

Figure 4: how audio recordings are used

There are several ways Google does this, such as temporarily modeling a user's voice (figure 3) or the audio review process (figure 4) which means that stored audio recordings are analyzed by trained reviewers. This literally means that employees will listen to one’s recordings. And even when users disable the voice & audio activity, Google is still allowed to use undeleted recordings for business purposes. In 2019, it came to light that Google employees had been listening to users' private conversations, which involved conversations that should have never been recorded in the first place. Research (Verheyden et al., 2019) found that these recordings not only contained sensitive information, such as bedroom conversations, but also professional phone calls containing private information, such as names, addresses and medical information. After this scandal, Google has adjusted its privacy policy as seen in figures 3 and 4, in which users are now informed about reviewers listening to their conversations. Google (2022) states “we take steps to protect your privacy as part of this process, for example, by disassociating your audio from your account”. But, it does not take a rocket scientist to recover someone's identity; employees simply have to listen carefully to what is being said. If they do not know how certain words are written, these employees have to look up every word, address, personal name or company name on Google. In that way, they often soon discover the identity of the person speaking (Verheyden et al., 2019).

Unmasking the dark side: exploiting data for personalized advertisements

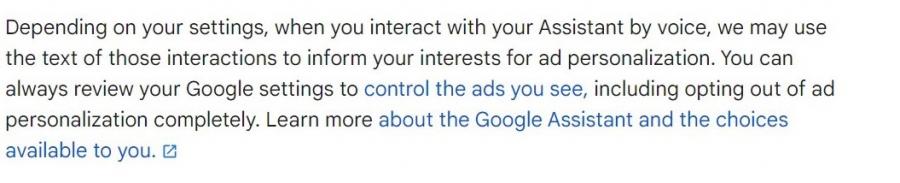

Lastly, what many people may not realize is that the voice interactions they have with their speaker influence the advertisements they subsequently encounter (figure 5).

Figure 5: how audio recordings are used for personalized ads

This means that if users have enabled certain settings, interactions with the Google Assistant can be used to personalize the ads one sees on Google. Thus, when a user interacts with the Nest speaker by voice, the text of those interactions can provide insights into their interests and preferences, which can influence the ads that Google is showing them. The usage of personal data for targeted advertising aligns with the concept of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019). By leveraging user data to deliver personalized advertisements, Google is utilizing surveillance techniques to generate revenue. The more detailed the data collected and the more effectively it can be used to target individuals, the more profitable the advertising model becomes. Although smart speakers are often used for everyday activities, they can also be used to remind users to take their medication or answer health-related questions. When (unintentional) transcripts of recordings containing sensitive information are used for personalized ads, they can be harmful and violate individuals' privacy as sensitive details are exploited for commercial purposes.

It does have to be recognized that while Google uses personal information for commercial purposes, they do give users options to control which data can or cannot be used. Users can choose to opt out of certain functions, like the storage of voice recordings. This way, the responsibility for privacy also lies with the user himself. However, companies like Google, always seem to find a way to maneuver around their own privacy policies. This has been proven by a series of scandals over the past few years. In 2022, Google was accused of still collecting location data from users even when they had explicitly turned off the location tracking setting. It was discovered that certain Google apps and services still collected location data, raising concerns about the company's compliance with user privacy preferences and the transparency of its data collection practices (Pietsch, 2022). Knowing this, there is a chance that consumers’ private information can be violated again if it has happened before.

McCreary's (2008) definition of privacy emphasizes the individual's ability to control their personal information and the decision to disclose it. When examining Google's practices, it becomes evident that they do not fully align with this concept of privacy. Yes, they changed their policy and gave users more control over their privacy. But, Google still collects big amounts of data. This data collection and the subsequent use of targeted advertising and personalized services violates the individual's control over their private information. So, do users really have full control? In the realm of privacy settings, it more seems like an illusion of control. Additionally, Google is also aware that many people do not even read privacy policies before consenting. According to a ProPrivacy.com study (Ivanfanta, 2021), 91% of consumers accept the terms of conditions of the policy without reading them. By making policies long and complex, it becomes less likely that individuals will invest the time and effort to understand the implications fully. So, how many people will actually be aware of what happens to the data they give away freely through voice interactions with their Nest speaker?

So, why do we continue to use these smart speakers? The reason for this can be explained through the eyes of the expository society. Harcourt (2015) states that “we are exhibiting ourselves through petabytes of digital traces that we leave everywhere, traces that can be collected”. By willingly adopting smart speakers and allowing them to listen and record our conversations, we contribute to the increasing expository nature of our society. The benefits they provide, such as voice-controlled assistance, entertainment, and home automation, can significantly enhance our daily lives. As a result, we may be willing to accept the trade-off of sharing private information in exchange for the convenience that smart speakers bring. This willingness to trade privacy for convenience reflects the norms and values of an expository society where personal data is willingly shared and exploited.

So, is it really just a simple voice command?

While interacting with the Google Nest speaker may seem nothing more than that, it is important to recognize that it is not as harmless as it appears. The findings of this paper shed light on the privacy concerns surrounding voice interactions with the Google Nest speaker. The analysis of Google's privacy policy reveals not only that they are continuously eavesdropped, but also that users' (unintentional) voice and audio data is collected and potentially accessed by both automated systems and human reviewers. This contradicts the concept of privacy as defined by McCreary (2008), which emphasizes individuals' control over their personal information. Moreover, transcripts of these recordings are generated and utilized to tailor advertisements specifically to us. This scenario opens the door to surveillance capitalism, where our private data becomes a commodity for exploitation. As we continue to embrace smart speakers and willingly share our personal data, we contribute to the growing expository society, where individuals are willingly sacrificing their privacy for convenience.

It is crucial to be aware of the implications of our choices as we interact with the ever-growing world of smart home devices and voice-controlled technology. Driven by convenience, we embrace the Internet of Things, without considering the risks it can entail. The convenience and efficiency these devices provide should not overshadow our right to privacy and control over our private information. Therefore, we must question the balance between the benefits and risks, as the decisions we make today will shape the future of privacy in our growingly connected world.

References

Harcourt, B. E. (2015). Exposed: Desire and Disobedience in the Digital Age. Harvard University Press.

McCreary, L. (2008). What was privacy? Harvard Business Review, 86(10), 123–130, 142.

Nest. (n.d.). Privacy Statement for Nest Products and Services. Nest.