Holocaust literature and ancient Greek tragedy

Comparing the role of the ‘witness’ portrayed in a Holocaust novel by Imre Kertész with Iphigenia’s role of the ‘tragic heroine’

Both the witness-role of Gyuri Koves in Kertész’s novel Fatelessness (1975) and Iphigenia’s role as tragic hero in Euripidean Greek tragedy share elements of victims and survivors abandoned to their fate. However, is it possible for a witness of the Holocaust to position himself as a tragic hero at the same time, or are these roles incompatible?

Introducing Kertész: the Holocaust as subculture and the link to ancient Greek tragedy

About the author

It has been little over a year ago since Hungarian author and Holocaust survivor Imre Kertész (November 1929 – March 2016) passed away. His oeuvre consists mainly of novels (as well as speeches, articles and translations) that deal with themes of dictatorship, personal freedom and the Holocaust. For this body of work he was awarded the Nobel Prize of Literature in 2002, for “writing that upholds the fragile experience of the individual against the barbaric arbitrariness of history” (Nobel Media AB, 2014).

Ever since the Second World War, we have been grappling with difficulties and questions surrounding the representation of the Holocaust through art and literature. Imre Kertész found a way of connecting (fictional) Holocaust literature to ancient Greek tragedy through his novels. Kertész (1929-2016), born of Jewish descent in Budapest, was deported to Auschwitz in 1944. From there he was transported to the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany, where he remained until the camp was liberated in 1945. Afterwards, Kertész moved back to Budapest to graduate high school and work as a journalist, translator and novelist.

On Holocaust literature and ancient Greek tragedy

Considering that the Holocaust has become an ever-present part of the world’s cultural memory, Kertész regarded the crucial functions of literature and art as the vessels of this memory. This is why he spoke of the Holocaust as a subculture, which he defined as a spiritual and emotional community, bound by a certain cult-like mentality (Kertész, 2011, p. 60). In this case, the mentality would be a passionate resistance to forgetting: “if the living memory of the events survives then it will survive not because of the official orations but, rather, through the lives of those who bore evidence” (Kertész, 2011, p. 59).

One of the questions that Kertész struggled with was whether the Holocaust could give rise to morality. Kertész argued for an affirmative answer to this question: “the Holocaust is a value, because through immeasurable sufferings it has led to immeasurable knowledge, and thereby [the Holocaust] contains immeasurable moral reserves” (Kertész, 2011, p. 77). The Holocaust was not just a historical event, but it cast an entirely different light on all our ideas about ethics and morality; it became a turning point in European history, against which would be measured all that happened before and after it. What is interesting about this line of thought, is that Kertész used the idea of the Holocaust as a moral reserve to create a link between the Holocaust and ancient Greek tragedy. He stated that, if preserved

“the tragic insight into the world of the morality that survived the Holocaust may yet enrich European consciousness (…), much as the Greek genius (…) created the antique tragedies that serve as an eternal model. If the Holocaust today has created a culture, as it undeniably has and continues to do, its literature may draw inspiration from the two sources of European culture, the Bible and Greek tragedy, so that irredeemable reality may give rise to redemption: the spirit, catharsis.” (Kertész, 2011, p. 77-78).

If it can indeed be said that Holocaust literature is capable of bringing forth morals and values like ancient Greek tragedy, it might be interesting to dive deeper into the similarities and differences between aspects of the two. Not just to see whether there are indeed concrete moral lessons to be learned from Holocaust stories, but to find out if it could provide new insights and opportunities in dealing with the inadequacies and risks of Holocaust representation.

This distinction between the externalized self and the internalized self as two perspectives from which Kertész’s novel can be viewed, complicates the role that he ascribes to the protagonist.

This paper is an initial attempt to look at a Holocaust novel through its connection to ancient Greek tragedy. Imre Kertész’s first Holocaust novel Fatelessness, which deals with his personal experiences regarding deportation and concentration camps, is analysed in the light of the Euripidean tragedies of Iphigenia at Aulis and Iphigenia in Tauris. Kertész already wrote about Goethe’s adaptation of Iphigenia in Tauris in one of his other Holocaust novels, called The Pathseeker, in 1977. Furthermore, Edith Hall (a British scholar of classics with a specialization in Ancient Greek Literature and cultural history) has written a very interesting article on Kertész’s novel The Pathseeker in connection to Iphigenia in Tauris titled ‘Greek tragedy and the politics of subjectivity in recent fiction’ (2009). This means that there might well be a deeper connection between the fictional Holocaust literature of Kertész and the story of Iphigenia written down in tragic plays by Aeschylus, Euripides and Goethe.

The first part of this paper will dive deeper into the concept of life-narrative and will examine the different roles that Imre Kertész assigned to himself when writing Fatelessness. From what perspective did he choose to write his novel and why did he choose that particular perspective over others? The second part of the paper will focus on the differences between four versions of tragic plays on Iphigenia. Aeschylus’s Agamemnon will briefly be discussed, as well as Iphigenia at Aulis and Iphigenia in Tauris by Euripides and the German adaptation Iphigenie auf Tauris by Goethe – which will prove to be useful for the comparison and analysis of Fatelessness and Euripidean tragedy in the third part of this paper. The paper ends with a conclusive part, focussing on Edith Hall’s notions of narrative control and narrative authority, in combination with the roles of victim, survivor, witness and tragic hero. It will show what similarities and tensions there are to be found when comparing ancient Greek tragedy to fictional Holocaust literature, based on the different roles ascribed to the protagonists of both stories. In particular, it will provide insight in whether a witness can also position himself as a tragic hero.

Fatelessness: Imre Kertész as life-narrator, from the role of victim to a witness position

About the novel and life-narrative

Several years after his liberation from Buchenwald, Kertész wrote down some of his personal experiences from the Second World War and tried to get it published as a novel. As for many Holocaust survivors, writing down experiences and memories served as a personal way of dealing with trauma: writing in order to try and understand what had happened during the Holocaust, and how it came about. The novel, which has now become Kertész’s best-known work Fatelessness (1975), was initially rejected for publication by the communist regime in Hungary, as it portrayed the suffering of a deported Jew in concentration camps in an unconventional way.

Fatelessness was written from the perspective of the 14-year-old Gyuri Koves, who is deported to Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Zeitz and survives these camps eventually. In his ‘The Holocaust as Culture’ (1992) symposium talk in Vienna, Kertész explains how writing from the perspective of a young boy helped him estrange himself from the narrative, which provided him with a perspective of observation (Kertész, 2011, p. 29-30). According to Smith and Watson this can be regarded as an example of life-narrative, which is characterized by the fact that the author writes about his own life (his memory is his primary source of inspiration) and does so from both an externalized and internalized point of view (Smith & Watson, 2001, p. 5). The writer then becomes both the observing subject and the object of observation, remembrance and contemplation – which results in the life-narrator confronting two lives: “one is the self that others can see (…), [but] there is also the self experienced only by that person, the self felt from the inside that the writer can never get ‘outside of’” (Smith & Watson, 2001, p. 5).

That his novel is absolutely authentic, that every aspect of the story is based on documented facts, is not something the author finds inconsistent with fiction.

This distinction between the externalized self and the internalized self as two perspectives from which Kertész’s story can be viewed, complicates the role that he ascribes to himself. The ‘inside self’, from which Kertész relives his personal experiences of his deportation to Auschwitz and Buchenwald through his fictional character Gyuri Koves in Fatelessness, is portrayed in the role of a ‘victim’. Kertész, as well as the fictional Gyuri Koves, is a victim of the Nazi regime that is picked up by the local authorities in Budapest. They are innocent protagonists of their stories, descending into the madness of a system in which they are caught. They are pulled into the reality of the deportations and concentration camps, and they are forced to give up their side-line position in exchange for a position as powerless prisoner. Because of the perspective of the ‘inside self’ in the novel, the first-person narrative is used: the main character of the story refers to himself as “I” in the book. This makes the events recounted and described by the narrator of the story highly subjective: since the narrator is in the story, he can only speak to his experience within it. This subjectivity in retelling an event is generally considered unreliable, because it lacks the insight into the larger whole in which the event and the victim are embedded: there is no helicopter view that puts the subjective experiences of the narrator into a wider perspective. In an effort of countering the possible side-effect of unreliability, and to gain an additional observatory perspective on his experiences and memories, Kertész employed two literary strategies.

A matter of perspective: literary strategies

First, he relocated the focus of his written work from his ‘internal self’ to an ‘external self’. By creating the fictional character Gyuri Koves, Kertész was able to distance himself from his own subjective experience by becoming the observer of what happened to Gyuri Koves in the novel (which indirectly means that he attempted to look from an outsiders’ perspective at what had happened to himself when he was deported and imprisoned in his youth). The protagonist of the story was no longer Kertész himself; the author purposely made it Gyuri instead. This observatory perspective – to which can be added that it was formulated years after Kertész’s own experiences with deportation and the camps, which left room for reflection over the years – provides the author with the needed helicopter view to put the events of the Holocaust into perspective and assign some kind of meaning to them. Apart from a subjective victim role, Kertész put on a more objective role as witness in writing Fatelessness: being able to watch events unfold from a side-line position, without intensely experiencing the emotions of the victim of the story to whom bad things happen. This translates into stylistic patterns in Kertész’s writing in Fatelessness: readers experience Gyuri’s story as distant and detached. In the novel, Gyuri automatically seems to rationalize everything that is going on around him and he barely passes (negative) judgment on the atrocities he encounters in concentration camps.

The second strategy Kertész employed to counter the subjective connotation to his written work is by turning an autobiographical story into fiction: Fatelessness is defined by him as a novel. Even though Fatelessness relies for a great part on his personal experiences of the Holocaust, Kertész has always denied it was an autobiography. In an interview with himself, which Kertész wrote down in what he referred to as a memoir, he both asked questions about his written works and he answered those questions himself as well. In this memoir, called Dossier K. (2006), Kertész explained how he did not consider Fatelessness to be an autobiography, since he did not “try as scrupulously as possible to stick to [his] recollections” (Kertész, 2006, p. 7). Where in an autobiography it would be most important to write everything down exactly as it happened, without varnishing the facts or purposely leaving things out, in a novel he found that the facts were not what mattered most – but precisely that what one added to these facts. That his novel is absolutely authentic, that every aspect of the story is based on documented facts, is not something the author finds inconsistent with fiction (Kertész, 2006, p. 8).

Fatelessness: the roles of victim, witness and survivor in protagonist Gyuri Koves

Deportation and honour

As I stated before, in general terms Fatelessness deals with the story of the Hungarian Gyuri Koves who survived his deportation to Auschwitz, Buchenwald and Zeitz. Gyuri was 14 years old and lived with his father and step-mother in a Jewish quarter of Budapest, when his father received a letter ordering him to be sent off to a labour camp. One morning, when Gyuri and his fellow workers were on their way to Csepel, their bus was pulled over by the Hungarian police. All Jews were taken apart and the bus was to continue to Csepel without the Jewish workers. More groups of Jewish workers were collected, and together they were locked into an empty building, before they were forced to march through the streets flanked by men in tight uniforms. Some workers tried to flee, but Gyuri did not consider that to be honest:

“But there was also something else that I felt, a sense of happy surprise I might call it, at the simplicity of an action; indeed, I saw one or two enterprising spirits then immediately make a break for it in his wake, right up ahead. I myself took a look around, though more for the fun of it, if I may put it that way, since I saw no other reason to bolt, though I believe there would have been time to do so; nevertheless, my sense of honour proved the stronger.” (Kertész, 1975, p. 55-56).

This fragment is illustrative of Gyuri’s complete lack of a sense of danger. While other workers who were rounded up tried to escape, Gyuri seemed completely unaware of what was going on. This was probably due to the fact that he was only a teenager, and not at all familiar with labour camps and concentration camps. This fragment also shows that Gyuri valued a sense of honour, even in situations that were out of the ordinary.

The character’s feelings of nostalgia or homesickness to the days he spent in the camps were what made the novel so unconventional that Fatelessness was initially rejected for publication.

After this incident, the workers were transported to Budakalász Brick Works, where they were sent to work for the Germans. This was no problem to Gyuri at all, as he saw the Germans as tidy, honest, industrious people with an appreciation for order and punctuality (Kertész, 1975, p. 63). Then a list is made where workers could write down their names if they wanted to volunteer to work for the Germans elsewhere. Gyuri is among those with an adventurous spirit who sign up, but soon he found out that they were actually transported to Auschwitz-Birkenau.

Gyuri is soon familiarized with life inside Auschwitz, and he often marvelled, in a detached and logical manner, on the complexity and the order of the concentration camp. When learning about the chimneys and the gas chambers for the first time, he is not shocked or scared by this piece of information, but it roused in him the sense of a joke or prank. However, “[t]he commanders’ fantasy then becomes reality, and as I had witnessed, there was no room for any doubt about the stunt’s success” (Kertész, 1975, p. 111-112). Gyuri explains how most of his time in Auschwitz could be defined by the words ‘boredom’ and ‘anticipation’. While there was not much more to do than eat, sleep and work, there was always a feeling that something was bound to happen. This is the sense of contingency that is ever-present throughout Holocaust literature: there is always an underlying feeling that from one moment onto the next the entire situation you were in could change.

Gyuri does not remain in Auschwitz very long, as he is soon transported to the Buchenwald concentration camp in Germany. Here, he felt quite at ease compared to Auschwitz: it was smaller, the guards were friendlier and the food rations per inmate were slightly bigger. This stay did not last very long either, because Gyuri is transported to Zeitz, a small labour camp near Buchenwald where there were more people than the camp could handle and where the conditions were much worse. Even though here too, Gyuri wanted nothing more than to be a good prisoner (“[m]ake no mistake about it, that was in our interest, that is what the conditions called for, that is what life there, if I may put it this way, compelled us to do”), he is quickly discouraged, because of a never-ending sense of extreme hunger and infections on his thighs (Kertész, 1975, p. 143). It is around this period that thoughts of suicide first appear in his mind:

“(…) and who has not felt that temptation, if only the once, a single time at least; who could remain unfalteringly steadfast (…): I, for one, could not, and I would undoubtedly have made an attempt, had [my friend] Bandi Citrom not prevented me from doing so time after time.” (Kertész, 1975, p. 158).

It is at this moment in his life that Gyuri’s rationalizing attitude is replaced with experiences of hopelessness and sadness. It was painful and disheartening for him to see his body deteriorate so quickly in a matter of months, and after carrying on for so long there came a day where he could take it no longer. “[B]y the end of the day I felt that something within me had broken down irreparably; from then on every morning I believed that would be the last morning I would get up” (Kertész, 1975, p. 170). Nevertheless, this had a peaceful impact on him. He lost all the importance and significance that he attributed to things before, and his daily activities were carried out mechanically. Being physically and mentally exhausted, Gyuri no longer cared about the consequences of his actions and in a way he just gave up.

Bandi Citrom is one of the inmates that helped carry Gyuri to the hospital wing of the camp. Gyuri was in a very bad state, but, little as they could do for him, at least he did not have to work anymore. The infections in his thigh were poorly treated, but it took much more to even remotely nurse him back to health. He was transported back to Buchenwald, where he ended up in a relatively more luxury hospital wing, where the staff treated their patients much better than in Zeitz. It is here that Gyuri spends his last days in the camp, before Buchenwald is liberated and Gyuri gets to travel back to Budapest, in search of his step-mother. The rationalizing mind of the main character of the novel, his reflection on moments of happiness experienced in the camps, and his final feelings of nostalgia or homesickness to the days he spent in the camps were what made the novel so unconventional that Fatelessness was initially rejected for publication.

Iphigenia in ancient Greek, and adapted tragedies: Aeschylus, Euripides and Goethe

The context of Iphigenia’s sacrifice in Aeschylus’s Agamemnon

While Kertész referred to Euripides’ Iphigenia in Tauris in particular in one of his novels, it would do well to explain Iphigenia’s story. In Aeschylus’ Agamemnon (Morshead, 2015) we learn about her father, king Agamemnon, who is readying his fleet with Menelaus in order to sail to Troy, to take part in what is now known as the Trojan War. When Agamemnon kills a sacred deer in one of the groves of Artemis and boasts about it, the goddess of wild animals and the protector of young women punishes him by calming the winds, to keep Agamemnon’s fleet from commencing its journey to Troy. Through Calchas, the well-known seer, Artemis reveals that Agamemnon needs to sacrifice his daughter Iphigenia, in order to soften her spirit and be able to set sail. Even though it breaks Agamemnon’s heart to think about killing his own daughter, Menelaus convinces him of the necessity of the sacrifice for the sake of the Trojan War. Agamemnon and Menelaus trick Iphigenia and her mother (Agamemnon’s wife) Clytemnestra into believing that Iphigenia will be married to Achilles at Aulis, after which Iphigenia is brought to the altar alone, where Agamemnon kills her to fulfil his sacrifice to Artemis. It is in Euripides’ Iphigenia at Aulis (Coleridge, 2014) that this story receives a different ending.

Iphigenia willingly consents to her sacrifice, declaring that she would rather die heroically and become renowned as the saviour of Greece, than to be dragged unwillingly to the altar.

According to the play by Euripides, while the sacrifice by Agamemnon is still required and Iphigenia is still tricked into coming to Aulis in order to marry Achilles, she and her mother meet Achilles before the supposed wedding. This is when they find out that they have been misled by Agamemnon and Menelaus, and Achilles confronts Agamemnon about this. As Agamemnon and all the Greeks present still think the sacrifice is necessary, and as Achilles appears on the brink of physically defending Iphigenia, the young woman realizes there is no hope of escaping her death. She gives in to the situation and willingly consents to her sacrifice, declaring that she would rather die heroically and become renowned as the saviour of Greece, than to be dragged unwillingly to the altar. At the very moment Agamemnon’s sword is to touch her skin, the goddess Artemis whisks Iphigenia from the altar and replaces her with a deer. Without anyone’s knowledge, Iphigenia is brought to Tauris where she is to spend the rest of her life serving king Thoas and fulfilling her duty as priestess of Artemis’ local temple. At this point, the story is picked up in Euripides’ Iphigenia in Tauris (Potter, 2014).

Continuation of Iphigenia’s life story in Euripides’s Iphigenia in Tauris

At the temple of Artemis in Tauris, Iphigenia ponders her lost relatives, whom see has not seen in ages and of whom she does not know whether they are dead or alive. While she hadn't heard of her parents in a long while, she is under the assumption that her younger brother Orestes has died fighting in Troy. When two Greek strangers come ashore in Tauris, it is her duty appointed by king Thoas to sacrifice them to Artemis by shedding their blood in the temple. As the temple is readied by her maids, Iphigenia enters in conversation with the strangers and asks them about their homeland and families. One of the strangers admits to originate from the same place as where Iphigenia was born, which issues her to ask him about her own father and mother. The stranger reluctantly tells Iphigenia that both her parents are dead: Agamemnon was killed by his wife Clytemnestra (who conspired against him with her lover Aegisthus at the time), and in turn the stranger says he killed Clytemnestra to avenge Agamemnon. When the stranger than states that he knows that Orestes is still alive and well, Iphigenia promises to let him go if the stranger travels back to Greece to deliver a letter to Orestes. The stranger convinces Iphigenia that he should not be the one to be released, but that his loyal friend and fellow captive Pylades should gain the honour. Pylades swears to Iphigenia that he will not rest until her letter reaches Orestes, at which he hands it to the stranger – revealing his friend to be Iphigenia’s lost brother Orestes. The three of them come up with a plan to escape from the temple and from Tauris, to return to Greece, in which Iphigenia plays an important part in deceiving king Thoas to let them out of everyone’s sight. Even though the plan does not fully work out, and a messenger brings it to the king’s attention that the trio is attempting to flee by boat, the king does not set his soldiers after them. After a divine intervention by goddess Minerva, the king concedes and calls back his men to let Iphigenia, Orestes and Pylades peacefully return to their homeland. It is this ending that Johann Wolfgang von Goethe in turn changed in his adaption of Euripides’ play called Iphigenie auf Tauris (Swanwick, 2005).

Predestined death of Iphigenia in Goethe’s adaptation Iphigenie auf Tauris

Goethe reworked Iphigenia in Tauris into a celebration of how one pure woman could heal the insanity and evils of the past, symbolized by the curse laid onto Orestes and the gruesome rituals of king Thoas at the temple of Artemis in Tauris. Orestes is subjected to a curse that was laid onto Tantalus, which is passed on throughout generations. Once upon a time, Tantalus stole food from the gods at mount Olympus and tried to trick them into eating a meal made up of human flesh afterwards. Thereupon, the gods cursed him and his male posterity to kill members of their family throughout the ages. Agamemnon, who is a great-grandson of Tantalus, fulfils this unfortunate destiny by sacrificing his daughter Iphigenia, and his only son Orestes in his turn kills his mother (Clytemnestra) to avenge the death of his father. Orestes is then chased to madness by the Furies, and begging the gods to lift Tantalus’s curse, he is ordered by Apollo to go to Tauris with his friend Pylades and bring back ‘his sister’ to Greece. Orestes, believing his own sister Iphigenia to be dead, interprets it as Apollo’s twin sister Artemis, whose wooden statue he needs to steal from her temple in Tauris and bring back to Greece. This is how Orestes and Iphigenia ended up in the same place at the same time in Tauris. Goethe highlights the madness of Orestes over killing his mother, and portrays Iphigenia as a noble-minded and sane woman that manages to calm him down. Iphigenia is also the one who stands up to the rituals of murder and bloodshed that king Thoas installed at Artemis’ temple in Tauris. Considering that she was rescued from sacrifice as well, Iphigenia appeals to Thoas’ humanity in giving up on that ritual. As the king thinks very highly of Iphigenia, and is about to ask her hand in marriage, he is inclined to concede to her wishes. By the time Iphigenia and Orestes recognize each other and decide to flee Tauris to return to Greece, she is the one who in the end calls off the planned deception of the king and tells him the truth. Goethe’s adaptation of the play ends with Iphigenia persuading the king to release her, Orestes and Pylades, and she appeals to his kindness – resulting in the three of them safely returning to Greece with Thoas’ blessing.

Comparing Greek tragedy to Holocaust fiction: sacrifice and resignation to one’s fate

On the theme of sacrifice

As I explained in the introduction, Imre Kertész referred to Goethe’s Iphigenie auf Tauris in his novel The Pathseeker (1977). This means that Kertész had a certain affinity with the Euripidean tragedy and that he believed the tragedy did not only suit the message of his novel, but also the topical content of his story. Considering that the topics of The Pathseeker and Fatelessness are the same (both refer to the Holocaust), we will be able to connect the Greek tragedies about Iphigenia to Fatelessness as well. There appear to be two main similarities between the Euripidean tragedy and Kertész’s novel, the first one of which is based on the theme of sacrifice.

How can it possibly be stated that an estimated 6 million Jews have been ‘sacrificed’ by those adhering to German Nazism or even by god?

In the tragedies concerning Iphigenia, the theme of sacrifice is very important. It is custom in Greek mythology to ‘sacrifice’ things, animals or people to the gods in order to invoke their mercy or help. This is the case for Agamemnon as well: he offends the goddess Artemis and has to win her favour again by sacrificing his own daughter Iphigenia. In a way that is regarded by most people as offensive, the Holocaust is occasionally viewed from a similar perspective. The name itself bears traces of sacrifice: ‘Holocaust’ originates from the Greek term ‘holókautos’, referring to an animal sacrifice offered to a god in which the whole (‘hólos’) animal was completely burnt (‘kautós’) (Whitney, 1904, p. 2859).

With regards to the victims of the Holocaust, the context of this term brings to mind the gas chambers and in particular the fire pits in which the bodies were burned. The trouble with this term lies in the meaning of the sacrifice for those who have been sacrificed, as well as in the goal for which the sacrifice took place. How can it possibly be stated that an estimated 6 million Jews have been ‘sacrificed’ by those adhering to German Nazism or even by god? From the viewpoint of Nazi ideology, were the Jews (and other victims of the Holocaust) ‘sacrificed’ for the benefit of the German people? How can we say that those 6 million Jews have ‘sacrificed themselves’ if there was no choice on their part to willingly let themselves be murdered under inhumane conditions in extermination camps? How can we state that Gyuri Koves in Fatelessness sacrifices himself in the way that Iphigenia resigned in her fate, accepted her own death and consented to her father sacrificing her for the sake of the Trojan War? Once again, for what purpose would the Jewish people have ‘sacrificed’ themselves? Would it have been a sacrifice in the name of their religion? A 'sacrifice' for God? A ‘sacrifice’ for mankind? A ‘sacrifice’ for Europe perhaps, as the Holocaust has been embedded in its historical, cultural, memory and is one of the few remaining things that unites Europe in contemporary times of rising populism and nationalism, and of political-economical division related to the European Union? It seems unnatural and inappropriate to think of the mass destruction of the Jewish population in terms of sacrifice, and yet the term ‘Holocaust’ seems to disagree with that statement.

On the theme of resigning to one’s fate

The second similarity between Iphigenia in Tauris and Fatelessness is a sense of resignation to one’s fate. As soon as Iphigenia finds out that she was never intended to marry Achilles, she is confronted with Agamemnon’s plan to sacrifice her for favourable winds that could lead the fleet of Greek warriors to Troy. Agamemnon and Menelaus, together with the Greek warriors present, all adhere to the necessity of the sacrifice, but counter-stories are heard as well, from Achilles in his defence of Iphigenia. Nevertheless, Iphigenia sees no hope to escape Agamemnon’s sword and therefore decides to die on her own terms: as a heroine and saviour, rather than as an unwilling and struggling victim. It was her personal decision to give in to her death, which, according to the versions of the story by Euripides and Goethe, was rewarded with her being whisked away by Artemis just in time. Iphigenia survived her sacrifice unharmed and was able to pick up a new life in a the city of Tauris, where, even though her parents had been killed, she is reunited with her brother who she thought had died.

While there is a difference between ‘giving in’ and ‘giving up’, regarding the conditions under which Iphigenia made her choice and under which Gyuri made his, both instances of accepting one’s fate in their respective situations lead to their survival.

Along similar lines, yet in a different sense, we see this resignation to one’s fate happening with Gyuri in Fatelessness. As described before, there was a moment during Gyuri’s imprisonment in Zeitz labour camp where Gyuri was so mentally and physically exhausted that he felt he could not go on anymore. In this moment, the fictional character let go of the meaning and importance he had previously attributed to being a good prisoner in the camp, which brought him a sense of peace and tranquillity. Giving up on doing your work properly meant punishment in concentration and labour camps, of which even death could be a consequence. Yet Gyuri stopped caring for what would happen to him if he failed to do his work and at that moment he gave up. While there is a difference between ‘giving in’ and ‘giving up’, regarding the conditions under which Iphigenia made her choice and under which Gyuri made his, both instances of accepting one’s fate in their respective situations lead to their survival. Where Iphigenia was saved by Artemis from the altar and brought to Tauris to build up a new life, Gyuri was carried to the hospital wing in Zeitz by some of his friends within the camp – which eventually meant that he was exempted from work and that he was more or less taken care of, before the camps were liberated and Gyuri regained his freedom, after which he could return to Budapest. However, Iphigenia seems to have been rewarded in both Euripides’ version of Iphigenia in Tauris and Goethe’s adaptation of the play, by being reunited with her brother and safely returning to Greece, thanks to her own honesty and the kindness of king Thoas in allowing them to escape. This reward seems far less visible for Holocaust survivors, or for Gyuri in particular, since victims were often traumatized to such an extent that ‘surviving their survival’ became a whole other challenge in its own right. Perhaps this is why the main character of Kertész’s The Pathseeker (1977) rewrites Goethe’s ending to Iphigenia’s tragedy in such a gruesome way: as a way to get even, or to set the record straight. According to this alternative version, king Thoas did not let the trio escape from Tauris, but instead ordered his men to attack and shackle Orestes and Pylades, while Iphigenia was sexually assaulted by various men. Thereafter, Orestes and Pylades were hacked in pieces before the eyes of Iphigenia and Iphigenia herself was murdered as well (Kertész, 1977, p. 86).

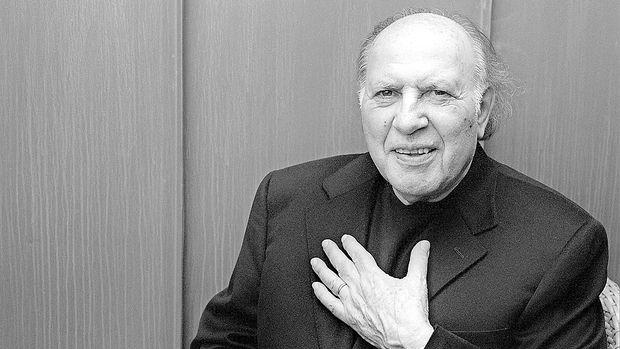

Imre Kertész in Berlin, 2009.

Fatelessness and Iphigenia’s tragedy: on narrative control, the tragic hero and the witness

Edith Hall discussed the use of Euripidean Greek tragedy in Imre Kertész novel The Pathseeker (1977) in an article titled ‘Greek tragedy and the politics of subjectivity in recent fiction’ (2009). According to Hall, Kertész referred to Iphigenia in Tauris in particular, because it draws attention to the epistemological issue of what she refers to as ‘narrative control’. She also remarks that the relationship between ancient Greek tragedy and recent fiction is heavily under-theorized, which is why she starts out in her article by exploring how Greek tragedy interacts with the question of rival subjectivities: “the radically different ways in which individual subjects can each experience the ‘same’ events” (Hall, 2009, p. 24). Through the effort of the novel’s main character (‘the Commissioner’) to rewrite Goethe’s adaptation of Iphigenia in Tauris, the narrative authority of both Euripides and Goethe is contested. Those were the versions “they want[ed] us to believe”, but ‘the Commissioner’s’ alternative version was what had “really” happened (Kertész, 1977, p. 86). Therefore there are three rival subjectivities established that all contest for narrative authority: that of Euripides, that of Goethe and that of ‘the Commissioner’. Edith Hall believes that this use of Euripidean tragedy in Kertész’s novel should be regarded as symbolizing the different rival subjectivities that exist about the narrative of the Holocaust as well. ‘The Commissioner’ tells a Buchenwald survivor he meets that he must “bear witness to everything” he has seen (Kertész, 1977, p. 80), which could point toward the different narratives about camp experiences from Holocaust survivors that were spread after the war. This does not relate to camp experiences of survivors alone, but can even be extended to narratives on the history of Nazi atrocities as established and upheld by entire governments.

The Euripidean play and its German adaptation were used by Kertész to address the issue of subjectivity and witnessing.

This is of course what links The Pathseeker (1977) to Fatelessness (1975), as the novel was purposely rejected by Hungarian Communist publishers due to its unconventional portrayal of the sufferings of a Holocaust survivor. Though fictional, Gyuri’s account of deportation and concentration camps was considered a rival subjectivity, a counter story, which the Hungarian Communist government tried to ban, as it did not fit the master narrative at the time. As reflected upon by Hall, the fact that Kertész used fiction “as a witness to real events of the twentieth century” might point to the specific way “in which this author [had been] received in central and eastern Europe” (Hall, 2009, p. 31). According to Hall, readers of Holocaust literature become “not so much a listener to a story, a memory, but a witness to ongoing acts of remembering, of reliving”, which has “profoundly influenced the representation of remembered experience and history more widely” (Hall, 2009, p. 28). Therefore, Hall claims that the Euripidean play and its German adaptation were used by Kertész to address the issue of subjectivity and witnessing (Hall, 2009, p. 30). In Fatelessness we see concrete instances of Kertész’s concern with the contested truth underlying events, which some people to this day, astonishingly, deny ever happened. As Gyuri returns to Budapest after his liberation from Buchenwald, he encounters a Holocaust-denier who asks him whether he had seen the gas chambers himself. Gyuri also meets an enthusiastic and opportunistic journalist who has already decided on his story and only hears from Gyuri what he can fit into his pre-existent narrative. Edith Hall finally reflects on how “history written by the winners can even entail wholesale extermination of the losers in order to prevent circulation of the rival narrative” (Hall, 2009, p. 32-33). This talk of winners and losers brings us back to the role of the tragic hero and the positions of the victim and the witness.

Winner nor loser

The first part of this paper has shown how Imre Kertész, in writing his novel Fatelessness, adopted two literary strategies to counter the subjectivity of his victim-role and to try and understand, from a side-line perspective, what had happened to him during the Holocaust. First of all, he turned his autobiography into fiction, while still maintaining his memory as a primary source of inspiration for the novel. Secondly, while deriving from his own personal (authentic) experiences, he created the fictional character of Gyuri Koves, through whose eyes we read about deportations and camp experiences in the novel. By positioning himself outside of the novel, with both a side-line position and a helicopter view on the story, he presented his ‘external self’, rather than his ‘internal self’, through the novel. Thereby he fashioned a role for himself as a witness, rather than (just) a victim, through whose experiences we learned about deportation and camp life in an emotionless and detached manner. The second part of the paper created an overview of the different rival subjectivities that all present a different view on the ancient Greek tragedy of Iphigenia. These rival subjectivities of Aeschylus, Euripides and Goethe proved of importance for questions surrounding the issue of narrative control in both The Pathseeker and Fatelessness by Imre Kertész. The third part of this paper reflected upon two main similarities between the Euripidean tragedies on Iphigenia and Kertész’s Fatelessness, which were the common themes of sacrifice and resignation in one’s fate. The latter theme clarified Iphigenia’s role as tragic heroine, because she had the courage to accept her death and consent to Agamemnon sacrificing her to Artemis for the sake of the Trojan War – which was subsequently rewarded as Artemis rescued Iphigenia from the altar and brought her to Tauris. The fourth part of the paper discussed Edith Hall’s reflection on issues of narrative control and narrative authority in Kertész’s written work. Considering that Kertész used Goethe’s adaptation to Iphigenia in Tauris to demonstrate rival subjectivities on the Holocaust, this serves as an explanation of our earlier findings on the author himself creating multiple subjectivities, through different roles, from the perspective of the victim as well as the witness.

It was impossible for me to be neither winner nor loser – I could not swallow that idiotic bitterness, that I should merely be innocent.

In conclusion, it can be stated that Kertész, from the position of the witness, can never position himself in the role of the tragic hero, because in self-fashioning (or identity subscription) the hero needs to take up an active role to establish him- or herself as a hero indeed. A witness, who is outside of the story and describes it from a side-line position, per definition attains a more passive role instead. Kertész seems to agree with this statement more or less, as he writes through Gyuri: “It was impossible, they must understand, (…) impossible for me to be neither winner nor loser, (…) that I was neither the cause nor the effect of anything; (…) that I could not swallow that idiotic bitterness, that I should merely be innocent” (Kertész, 1975, 260-261). To be unable to see himself as a victor (survivor) or as a victim, and to regard oneself as merely innocent, means that Kertész at that point identified himself more with his ‘external self’ (positioned as the witness) than with his ‘internal self’ (positioned as either victim, or survivor).

From the perspective of the role of the victim or survivor alone, Kertész (through his fictional character Gyuri) can most certainly be regarded a tragic hero – however not through identity subscription (self-fashioning), but through identity ascription instead (being assigned an identity from an external source). Victims, or survivors, of the Holocaust will rarely refer to themselves as a tragic hero of some kind, likely because there is often a form of ‘survivor’s guilt’ present and because the life after liberation was still very difficult to live. Nevertheless, through external sources, such as the reader of the novel, Kertész (through Gyuri) can be assigned the role of the ‘winner’; the role of the tragic hero. Gyuri’s tragedy, for instance, can be seen as his failure to accept the meaninglessness of the atrocities of the Holocaust, which is portrayed through his continuous efforts of rationalizing what is happening around him. However, this tragedy can also be interpreted as his triumph. By focussing, through Gyuri’s final reflections on nostalgia and homesickness towards his days in Buchenwald, on the moments of relative happiness in the camps – instead of on the atrocities – Gyuri claimed victory over the mind games the Nazis played in the camps.

References

“The Nobel Prize in Literature 2002 to Imre Kertész – Press Release”. (2014). Nobelprize.org. Nobel Media AB.

Aeschylus (n.d.) Agamemnon. Translated by E. D. A. Morshead. (1909). Adelaide: University of Adelaide.

Euripides (n.d.). Iphigenia at Aulis. Translated by Edward P. Coleridge. (1891). Adelaide: University of Adelaide.

Euripides. (n.d.). Iphigenia in Tauris. Translated by Robert Potter. (1781). Adelaide: University of Adelaide.

Hall, E. (2009). 'Greek tragedy and the politics of subjectivity in recent fiction'. Classical Receptions Journal, 1(1), 23-42. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kertész, I. (1975). Sorstalanság. Translated by Tim Wilkinson as Fatelessness. (2004). New York: Vintage Books – A Division of Random House, Inc.

Kertész, I. (1977). A nyomkeresõ. Translated by Tim Wilkinson as The Pathseeker. (2008). Brooklyn, New York: Melville House Publishing.

Kertész, I. (2006). Dossier K. Translated by Tim Wilkinson. (2013). Brooklyn: Melville House Publishing.

Kertész, I. (2011). A Conversation with Imre Kertész. (2010). The Holocaust as Culture. Translated and introduction by Thomas Cooper. (2011). Calcutta, India: Hyam Enterprises.

Kertész, I. (2011). A Holocaust mint kultúra. (1992). Translated by Thomas Cooper as ‘The Holocaust as Culture’. (2011). The Holocaust as Culture. Translated and introduction by Thomas Cooper. Calcutta, India: Hyam Enterprises.

Kertész, I. (2011). Imre Kertész and the Post-Auschwitz Condition. (2011). The Holocaust as Culture. Translated and introduction by Thomas Cooper. (2011). Calcutta, India: Hyam Enterprises.

Smith, S. & Watson, J. (2001). Reading autobiography. A guide for interpreting life narratives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Von Goethe, J. W. (1786). Iphigenie auf Tauris. Translated by Anna Swanwick as ‘Goethe’s Iphigenia In Tauris’. (2005). New York City: 4 Cooper Institute, Project Gutenberg.

Whitney, W. D. (1904). “Holocaust”. The Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia.