@IamSophieScholl: Instagram meets 1942

The social media project @IchBinSophieScholl (@IamSophieScholl) innovates the German remembrance culture of Nationalist Socialist times in the 21st century. Under the slogan “Imagine its 1942 on Instagram”, the Südwestrundfunk (SWR) and Bayerischer Rundfunk (BR) launched an Instagram account that aims to bring the historical figure Sophie Scholl from the history books into the present times through the affordances of social media. In light of the resistance fighter's 100th birthday, the multimedia project presents Sophie Scholl's (political) life during the Nazi regime resistance in an “emotionally, radically subjective way in simulated real-time” (SWR, 2021). Between the 4th of May 2021 and the 18th of February 2022, Instagram followers were able to witness and engage with the last ten months of Sophie’s life starting with her move from Ulm to Munich (4th of May 1942) and ending with her arrest (18th of February 1943). The historical figure Sophie Scholl is reimagined through actress Luna Wedler, who portrays her persona. Other actors “bring back to life” brother Hans Scholl, friends, other members of the White Rose ("Weisse Rose") resistance group, and Sophie's love interest; Wehrmacht officer Fritz Hartnagel. At its peak, the account reached 930.000 followers (Korsche, 2022). The account combines documentary and fictional elements as it mixes archival material and historical facts with fiction, storytelling, and dramatizing elements. The creators of the social media project describe @IamSophieScholl as “fiction based on real events” (SWR, 2021).

This article will investigate the Instagram account’s tension between fact and fiction. The article will start off by explaining who Sophie Scholl is to provide the necessary background information. Next, the Instagram account will be analyzed in light of its ability to present the historical figure truthfully by drawing on the theoretical work of Aharon Appelfeld and Berel Lang in Harrison (2006). Aharon Appelfeld and Berel Lang argue that fictional representation cannot be truthful to the historical realities of the subject matter. Contrastingly, Harrison (2006) points out the benefits of fictional representation. This research aims to answer the question: can the Instagram account @IamSophieScholl provide a truthful representation of the historical realities of the White Rose resistance fighters in their struggle against the National Socialist regime? As such, this academic work contributes to the study of World War II remembrance with an emphasis on the role of facts and fiction in truthful representation.

Sophie-who?

Sophie Scholl is a German national hero represented in history books, museums, and WWII education because of her courageous resistance against the horrors of the Nazi dictatorship. Sophie was born in May 1921 in Baden-Würtenberg as one of six children. At ten she moved to Ulm. As Hitler’s NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers' Party) rose to power, its propaganda was highly effective and also influenced Scholl. She joined the youth organization BDM (Bund Deutscher Mädels) alongside many young German girls. However, her father Robert influenced her rethinking of National Socialism as he was a staunch critic of the Nazis. As a result, Sophie was exposed to critiques of the regime, in contrast to the majority of the general public. Her eventual rejection of National Socialism was furthermore prompted by the arrest of her brother Hans in 1937 (Malloryk, 2020).

In 1942 Sophie moved to Munich to study at the Ludwig Maximilian University alongside Hans who had been released after his arrest. There she learned of the youth resistance movement ‘The White Rose’ that her brother had founded and she joined the movement. The White Rose was comprised of students from the University of Munich who engaged in acts of resistance by circulating resistance leaflets and they used graffiti to spread slogans such as ‘Down with Hitler’ and ‘Freedom’ in Munich. Their actions aimed to expose Nazi crimes, criticize the regime, and call for resistance against the war and the Nazi state (Malloryk, 2020).

On the 18th of February, Sophie and Hans distributed recruitment flyers which called upon fellow students to join the White Rose. First, they strategically placed flyers in the halls of the university to be found. Then Sophie threw a pile of flyers off a railing making them fall down into the university's central hall; an iconic scene that has become a staple component of any documentary about Sophie Scholl and the White Rose (see cover photo). Sophie and Hans were arrested by the Gestapo (Geheime Staatspolizei) after the protest. Four days later, both Sophie and Hans were charged with high treason and were executed alongside other members of the White Rose. Sophie died at the young age of 21 (Malloryk, 2020).

Figure 1 Sophie Scholl

Theoretical framework

The following concepts and theories will be instrumentalized to analyze whether the @IamSophieScholl project gives a truthful representation of Sophie's historical reality.

The Shoah survivor and novelist Aharon Appelfeld points out that World War II testimonies such as memoirs are commonly labeled as “authentic expressions of reality” while fictional Shoah literature is understood as “fabrication” (Harrison, 2006). Appelfeld argues against the ability of fictional literature to authentically convey the reality of the Holocaust and as such appeals to the “moral objective” to present the past with historical accuracy, out of respect for the victims and a responsibility to be truthful and factual (Harrison, 2006).

The scholar Ben Lang continues this argument by adding that the use of fiction grants authors the freedom to employ different narrative techniques and descriptions when addressing a subject. However, this creative freedom also poses a risk of presenting distorted accounts of the Holocaust, as personal biases and choices can influence the portrayal and interpretation of historical events. According to Lang, the genre of fiction enables the author to invent and reconstruct. He argues that “fiction can only reveal how its author imagines things, not how they actually are” (Harrison, 2006).

The project blurs the line between fact and fiction as historical archived material is combined with a fictive narrative and storyline construction

Contrasting this pessimistic view towards fictional Holocaust literature, Harrison (2006) describes the benefits of fictional representation. Fiction provides the opportunity for readers to have the feeling of becoming an inhabitant of an alien ‘Lebenswelt’ comprised of an unfamiliar collection of practices or circumstances. It provides readers an opportunity to completely and unreservedly immerse themselves in the perspective and circumstances of an individual. So, while factual literature provides knowledge about an alien situation, fictional literature gives us knowledge of what this alien situation feels like (Harrison, 2006).

While these three arguments focus specifically on the presentation of the Shoah in literature, they can also be employed in the context of this article. I will apply the arguments to the social media representation of the historical reality of Sophie Scholls Nazi resistance fight.

@IamSophieScholl: The blurred line of fact and fiction

The multimedia project @IamSophieScholl educates young audiences about the historical figure Sophie Scholl and aims to keep her remembrance alive. Her story unravels in “simulated real-time” (SWR, 2021) on Instagram by making use of the platform's affordances. Played by an actress, “Sophie Scholl” posts daily stories in which she gives insights on life during the Nazi regime by highlighting activities of her and fellow members of the White Rose. Partially, these stories are filmed at the original historical locations such as the University of Munich. Besides stories she also posts pictures, drawings, Nazi propaganda posters and newspaper articles of the time to give insights into the historical past. These posts are accompanied by descriptions of “Sophie”. Additionally, “Sophie Scholl” answers questions and engages in conversations in the comment section of her profile. The creators explain that the basis for the fictionalized historical figure lies in factual information derived from documents and Sophie Scholl's diary entries dating back to 1937. Moreover, several WWII historians were involved in the creation process (SWR, 2021).

The project blurs the line between fact and fiction as historical archived material is combined with a fictive narrative and storyline construction. The creators have made the decision to exclude explicit references to the historical material for two reasons. First, they argued that implementing sources could cause them to lose the interest of the young target group. Secondly, they made the artistic decision not to break with the fictional format of the project (Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung für die Freiheit, 2021). As a result, viewers are not able to distinguish between fact and fiction; between the real Sophie Scholl and the represented Sophie Scholl. This raises the question whether this project provides a truthful representation of her historical reality.

The fictional storytelling of Sophie Scholl’s life in combination with the rejection of references leads to the decontextualization of historical facts

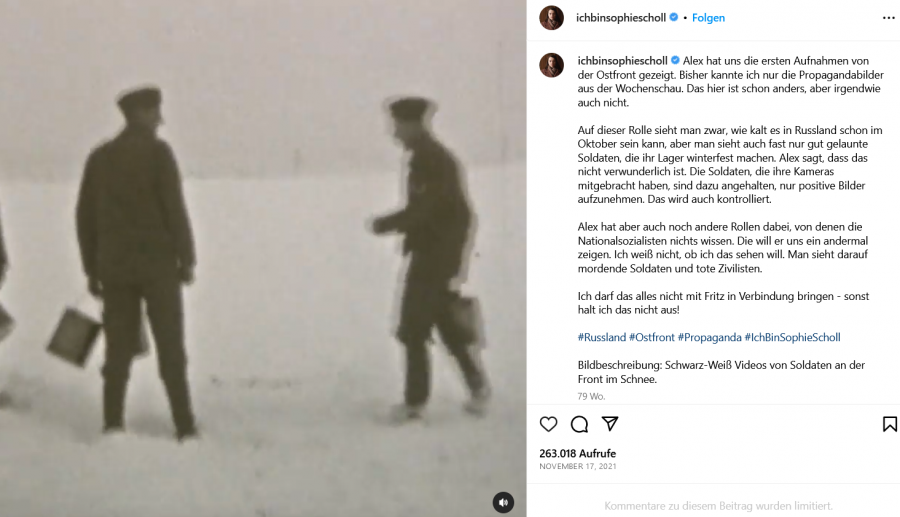

In Appelfeld’s words, @IamSophieScholl is a “fabrication” rather than an “authentic expression of reality” (Harrison, 2006) due to its fictional format. On top of that, we can derive from Lang (2006) that the fictional narration gives the authors the creative wiggle room to invent and reconstruct, which influences the accuracy of the historical description. This can, inter alia, be seen in the example of a post from November 17, 2021 (See Figure 2).

Figure 2 Recontextualization of imagery. Translation: Alex showed us the first recordings from the Eastern Front (...)

The description of the post by “Sophie” suggests that the video imagery is taken by the White Rose member Alex. However, when asked whether the video was actually taken by Alex, "Sophie" answers (Figure 3) that it is archive material from an unknown source and that it was not taken by a White Rose member.

Figure 3 Answer to follower question Translation: The shown pictures are not by a member of the White Rose. It is archive material from the second world war from an unknown source

This shows how the fictional storytelling of Sophie Scholl’s life in combination with the rejection of references leads to the decontextualization of historical facts. Hence, it could be said that historical accuracy is sacrificed in favor of creative freedom.

The same can be seen in a post from February 1st (Figure 4) in which “Sophie” tries ‘Panzerschokolade’ which is not grounded in historical facts but is a result of creative narration.

Figure 4 Sophie trying ‘Panzerschockolade’

Another example of this can be seen in a post from the 22nd of October 2021 (Figure 5).

Figure 5 Sophie showig how to bake honey bread

This post highlights how the fictive narration choices of the authors create fabrications of what could have been, but not of what really was as this fictional “Sophie Scholl” recipe finds its origin in historical facts, yet is presented without this contextualization. This shows that the project lacks transparency in terms of mixing fiction and historical facts. As a result, followers are left in the dark about where the facts end and fiction begins. Thus, arguing on the theoretical ground of Appelfeld and Lang the project combines facts with fictional narration that enhances the fabrication of Sophie Scholl. It does not deliver a historically accurate representation of Sophie Scholl's realities.

Emancipation from pure facts

We have learned that @IamSophieScholl is a fabrication and not an authentic expression of Sophie Scholl’s reality since it incorporates fictional narration and storytelling components that reconstruct, recontextualize, and invent anecdotes. This begs the question whether this is necessarily a bad thing?

The creators have taken artistic liberties to construct a narrative that does not always align precisely with historical events

Following Harrison (2006) this question can be answered with a no. Quite the contrary in fact. The fictionalization of Sophie Scholl is beneficial for the follower since it gives the opportunity to become a dweller of her alien ‘Lebenswelt’. The audience can completely and unreservedly immerse herself in the perspective of Scholl and her circumstances as a resistance fighter under Nazi rule. The Instagram account allows viewers to become part of the resistance “in propria persona'' (Harrison, 2006) having secret meetings with the White Rose, composing, printing, and distributing flyers, or just experiencing the daily life of a young woman during times of tyranny and war. They become immersed in the alien life of the young resistance fighter by which they also gain knowledge of the Nazi times and an insight into its effect on individuals who showed civil courage. Fictional aspects such as “Sophie” trying Panzerschokolade contribute to drawing her ‘Lebenswelt’ in and makes the ‘Zeitgeist’ of the 1940s more relatable for the audience. Through the style of fictional narration, the audience can have a richer and more meaningful experience, delving into the complexities of Sophie Scholl's life while keeping in mind that artistic liberties are taken by the creators. As such, the project does not give knowledge about the alien situation as factual representations in the way that life-writing pieces or biographical documentaries do. Instead, the fictional representation of Sophie Scholl gives knowledge of the ‘Lebenswelt’ including the horrific circumstances, unparalleled experiences, and extreme emotions of her life (Harrison, 2006). This also enhances the emotional engagement of viewers which can encourage empathy, reflection, and sensibility.

Lydia Leipert, the editor responsible for @IamSophyScholl from the Bayerischer Rundfunk, explains the decision for this hybrid form of fact and fiction: “I believe that you can only reach and capture people with a clever storyline that is telling enough to provide knowledge transfer” (re:publica, 2022). The success of the project underlines her way of thinking as over 900.000 people delved into the last months of Sophie Scholl’s life.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Instagram project @IamSophieScholl, which aims to bring the historical figure of Sophie Scholl into the present through social media, presents a tension between fact and fiction. The project blurs the line between the real Sophie Scholl and fictionalized fabrication, by combining archival materials, historical facts, and fictional storytelling.

Drawing on the theoretical perspectives of Aharon Appelfeld and Berel Lang it becomes clear that the project cannot provide a completely truthful representation of Sophie Scholl's historical realities. The scholars argue that fictional representations, by their very nature, deviate from historical accuracy and can be influenced by personal biases and creative choices. This is evident in @IamSophieScholl, where the creators have taken artistic liberties to construct a narrative that does not always align precisely with historical events. However, Harrison's (2006) perspective sheds light on the benefits of fictional representation. Despite the project's departure from pure historical facts, it offers viewers the opportunity to immerse themselves in Sophie Scholl's world, fostering empathy, reflection, and a deeper understanding of the experiences of resistance fighters during the Nazi regime.

While the project @IamSophieScholl may not provide an authentic expression of Sophie Scholl's reality, it succeeds in capturing the attention and interest of a substantial audience and effectively educates it about Sophie Scholl's courageous resistance against the Third Reich. The emotional engagement and immersive nature of the project contribute to its success in conveying the complexities of Sophie Scholl's life, encouraging empathy and fostering a sense of historical sensibility among the audience.

References:

Friedrich-Naumann-Stiftung für die Freiheit. (2021, May 25). @ichbinsophiescholl - Die Widerstandskämpferin in der Gegenwart [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SRHKaDsm3xE

Harrison, B. (2006). Aharon Appelfeld and the problem of Holocaust fiction. Partial Answers: Journal of Literature and the History of Ideas, 4(1), 79–106. https://doi.org/10.1353/pan.0.0098

Korsche, J. (2022, July 6). Instagram-Projekt “ichbinsophiescholl” Erreichte Kaum Jugendliche. Süddeutsche.de. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/medien/sophie-scholl-instagram-1.5615439

Malloryk. (2020, February 21). Sophie Scholl and the White Rose: The National WWII Museum: New Orleans. The National WWII Museum | New Orleans. https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/sophie-scholl-and-white-rose

re:publica. (2022, June 10). re:publica 2022: @ichbinsophiescholl - Ein Instagramaccount für die NS-Widerstandskämpferin [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QBYTajHmdoY

SWR. (2021, April 26). Projekt & FAQ. swr.online. https://www-swr-de.translate.goog/unternehmen/ich-bin-sophie-scholl-proj...