‘Onions’ among Estonians: Cultural diversity in the country of startups

All my life I’ve been asked what my nationality is, who I am, but I never had an answer. Officially, I’m Estonian, as my mother was born on an Estonian island called Saaremaa where people barely speak anything else except Estonian. But my first language is Russian - I got to attend Russian school, most of my friends are Russian language speakers, my biggest entertainment is to watch Russian YouTube…

So who am I: Russian or Estonian? Neither and both at the same time. We call ourselves “Russian speaking Estonians”. We are a specific type of citizen of Estonia, a small country in the north of Europe with a population of only 1.3 million people. The official language of Estonia is Estonian, although around 25% of the people speak Russian.

This paper is based on research work I have carried out in 2021, consisting of a literature review and interviews with primary sources, i.e. my mother and Russian-speaking acquaintances. I believe it would be interesting to see possible changes in the relationship of language-diverse citizens in Estonia especially considering recent news about the Russian invasion in Ukraine.

Languages in Estonia

Estonia is a small country in the northern part of Europe. The roots of the Russian language in Estonia come from history. Starting from the Second World War till the beginning of the 1990s Estonia was a part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Despite the Estonian language being widely used throughout the country, Russian and German were right behind the corner. The Russian language somewhat replaced German in the official and educational spheres, especially in the late 19th - early 20th centuries. Nevertheless, the bulk of the Estonian-speaking population during this period continued to develop away from both languages, although both German and Russian began to exert a strong influence on the vocabulary of the literary Estonian language. During the 19th century, the geographical picture of the spread of the Russian language in the country was gradually established, which remains in general terms to this day. The Russian language had the strongest positions in the northeast of the country, in regions geographically close to the capital of the Russian empire - St. Petersburg.

The lack of knowledge of the Estonian language among Russians speaking residents is often associated with a geographical feature, or rather, with the neighbourhood with Russia. Ida-Virumaa is the province of Estonia, located the closest to the Russian border. According to research by Äkki Magazine (2021), the number of Russian speakers in Ida-Virumaa has risen from 61% in 2015 to 74% in 2020 as the number of delivered babies in this part of te population is higher than in the Estonian speakers.

“Due to the influx of the Russian speaking population, after Estonia was incorporated into the USSR in 1940, the share of the Russian speaking population began to grow rapidly. A significant part of the Estonian-speaking inhabitants of Ida-Virumaa switched to using the Russian language but continued to consider the Estonian language as their native language.” (Äkki Magazine, 2021)

In 1991, after Estonia was acknowledged as an independent country, the Russian language was deprived of its official language status, and even nowadays it is considered a foreign language.

Picture 1: The map of Estonia

One of the biggest examples of the Russian impact on Estonian culture and identity is the city called Narva. In 2020-2021, the population of the city of Narva, Estonia counted 57,650 people. In Narva, Russian is the main language for normal conversation, even though Estonian remains the official language in the whole of Estonia.

“The city’s Russian speaking inhabitants (comprising over 90% of the local population) were particularly affected by Estonia’s attempts to consolidate the dominant position of ethnic Estonians in society. To date, 15.3% of Narva’s population still hold undefined (non-)citizenship, 36.3% have taken up Russian citizenship, whereas only 46.7% have Estonian citizenship.” (Jašina-Schäfer & Cheskin, 2019)

That is why almost all signs and notices in the city are bilingual.

Although the number of Russian speakers is so big, not all of them consider themselves a part of Russia. The research from Jašina-Schäfer and Cheskin (2019) tells the story of 45-year-old Marina, who lives in Narva. She points out that after every trip to Russia she was still happy to come back home.

"I’ll tell you now one of my school memories. We were travelling a lot with my class, we went to Moscow, to St. Petersburg. I liked it everywhere. But there is this turn to Narva when our castle becomes visible. When the bus would turn, and you would see the Hermann Tower. I would immediately get tears – this is my native place [rodnoe], this is my home. And I would say: I am finally home.” (Jašina-Schäfer & Cheskin, 2019)

Grey passports and the citizens of nowhere

The closer we got to the collapse of the USSR, the more confused people in Estonia became. They had no clue what was going to happen with their country, as they considered the USSR their home; what was going to be next, what name would we have, what currency, what language, etc. - they had no clue what was waiting for them afterwards. One of my friends’ dads told me a story once:

“Right before the USSR was going to collapse, local volunteering citizens in Tallinn started to collect signatures. We’ were told that we could either sign up the sheet, agreeing to in theory become an Estonian citizen in the future, or leave it blank and stay ‘in the middle of a crossroads’. We had no clue what this “crossroads” meant. After some time, the ones that signed the paper got to have an Estonian, blue passport, while others got grey ones. Grey passport is a passport of nobody - I have become a citizen of nothing, neither Russian nor Estonian.”

“In 1996 the Estonian government started issuing “grey passports” (“alien’s passport”) to non-citizens, thus granting them a permanent right of residence in Estonia.” (Hoffmann & Makarychev, 2017)

An Estonian Alien’s Passport (Estonian: Välismaalase pass) is, as stated by the Estonian Police and Border Guard Board (Estonian: Politsei- ja Piirivalvemaet):

“a travel document issued by the Republic of Estonia to certain foreigners. The alien’s passport is issued to foreigners who have a valid Estonian residence permit or right of residence and it is proved that they lack a travel document issued by a foreign country and it is not possible for them to obtain one.”

According to the Population Register, as of July 1, 2020, 69,993 people lived in Estonia who had not decided on their citizenship. These people often tend to have a feeling of being “a stranger among your own” (Jašina-Schäfer & Cheskin, 2019).

"In addition to grey passports, the governments presented “personal identity cards”, established in 2002 to implement Estonia’s digitization policy and enhance the use of respective instruments (such as a digital signature), and were extended to non-Estonian citizen residents as well. Today, altogether 1 207 493 inhabitants possess an Isikutunnistus." (Hoffmann & Makarychev, 2017) [“Isikutunnistus” in Estonian is the Identification Card (ID)].

Picture 2: Alien passport (grey) and Estonian passport (blue)

In order to get an Estonian blue passport - firstly, you need to have a long-term residence permit or permanent residence right, that means that you have lived in Estonia on the basis of a residence permit or a residence right for at least 8 years, of which 5 years on a permanent basis. Secondly, you have passed the Estonian language proficiency test. The Russian speaking part of the country, although, states that the exam itself is quite a struggle, especially in modern Estonia. Your level must be quite high to call it sufficient in order to pass it successfully. Lastly, you have to pass the examination on the knowledge of the Constitution of the Republic of Estonia and the Citizenship Law, and some more other requirements. If you need any help with getting an Estonian passport, you know where to find me *winks*.

My mom’s opinion

My mom is one of the living examples of a person that got to experience all this herself. My mom was born on the biggest Estonian island called Saaremaa, but at an early age, she had to move to the Russian part of the USSR, as her father was a military frontier guard. That is why her main and then native language became Russian. It’s been a while now and she has recently turned 60 years old. She has lived through the USSR, its collapse, and its consequences. I asked her several questions about her opinion on this topic. One of the questions was: “What did it feel like living through the collapse of the USSR?”. She explained:

“First years when the USSR collapsed we [Russian speakers] felt like invaders. Estonian speakers were saying that Estonia was forcefully made to stay (as a part of the USSR). These times were very complex, messy. Estonian speakers had a twofold attitude towards Russian speakers.” “...The collapse has changed our world dramatically, we got to choose between 3 outcomes. First, move to Russia and become its citizen. Second, become nobody and live with the grey passport, when no one would ask you to learn Estonian. And third, staying, passing the Estonian proficiency test, the constitutional examination, and having a blue passport. ...They closed a lot of soviet factories and manufacturers, and hundreds of people became jobless. The ones that agreed to learn Estonian were offered free language courses and better-paid working places.” Then I asked her about documents and legal aspects of the collapse. “Some people decided to leave Estonia, “ she pointed out. “They were even offered some money by the Russian government to leave. The ones that stayed got green Transfer Papers, which allowed you to still easily travel to Russia.”

At that period of time, several years after the USSR collapsed, some people were still believing that Russia was their home.

Not a lot has changed from the late 1990s in this sense - a big number of grey passport owners, almost 70,000 in 2020 as stated before, still decline the opportunity to become a citizen, they prefer freely travelling to the Russian Federation.

The contemporary situation

Nowadays Estonia is a very developed country of the future. Estonia is a country with one of the biggest number of (successful) startups. In 2021 we call Estonia ‘E-Estonia’:

“From voting to signing documents to doing taxes online, Estonia implements a hassle-free and modern approach to doing errands.'' (Siim, 2021)

The Internet can be found even in the most secluded place of the country, 99% of all services are online - voting for the Parliament, signing official documents, doing everything concerning finances, checking recent health receipts, registering a company, asking for help from the police department, etc. The best part of it is that all the governmental websites are at least in 3 languages - Estonian, English and Russian, although some of them also include Finnish.

Now back to the topic - according to the Tallinn City Government, there were 445,688 registered residents in Tallinn on 1 January 2021. As for the Russian speaking population, the official Estonian database points out the number of 156,670 citizens, which is a bit more than 35% of the population. I am a part of this 35%. As my mom’s first language was Russian, that's the language I spoke my first words. The kindergarten I went to was for Russian speaking kids, both my middle and high schools were taught mostly in Russian. Why do I say ‘mostly’? Because Russian speakers are being made to speak and learn Estonian. A lot of high schools practice the idea of a bilingual school, where subjects are taught 60% in Estonian and 40% in Russian. Unfortunately, or maybe, fortunately, that is only what the papers say. In reality, the classes in my high school, for instance, that had to be originally fully taught in Estonian only had books in Estonian, when all the slides and notes were taken and given in Russian if not English.

Languages in education

The Estonian government once had an idea to mix Estonian speaking and Russian speaking kids together to make them create a new, completely bilingual society, where Russian speaking kids would be speaking Estonian fluently and Estonian speaking kids would be… The same. Nothing would dramatically change. I mean, some of those ideas were to also include Russian as a mandatory FOREIGN language, but the initial idea was to cancel Russian speaking schools and make everybody study together to 'not break the cultural aspect of a society'. Although I can fully understand their logic, some people disagree.

Even if a while ago this idea was just an idea, now modern politicians and party members decided to act immediately. According to the Government of the Republic’s website, the leader of the Reform Party Kaja Kallas and the chairman of the Centre Party Jüri Ratas signed an agreement on the formation of the government on 25 January 2021. One of the subsectionsof this document stated:

“We are launching an action plan for education in Estonian to give everyone an equal opportunity to participate in society and working life and to continue their studies at the next level of education. We allocate the necessary funding to kindergartens and schools, which enables us to organise the study process in Estonian, ensuring high-quality education. We bring additional teachers with appropriate qualifications to educational institutions.”

It sounds great, and I do agree that the Russian speaking part of society cannot fully compete on the same level with Estonian speakers due to their lack of proficient Estonian. However, most of the people I have talked to believe that by completely getting rid of Russian we lose a sufficient cultural aspect of our country.

The initial idea of this paper and my little research project was to show others the situation where Russian speakers are the minority, and this is a perfect example.

Youngsters' opinions

I was curious what my friends and acquaintances think of the present situation of the Russian speaking community in Estonia. I posted a bunch of questions on my Instagram Stories, and got much more answers than I was expecting - people were shaking with anger, how much they had to tell me about this topic. The approximate amount of answers I got is 50 to 60, and around 30 of them have reached out directly to me in order to explain their position and argue either for or against the statement.

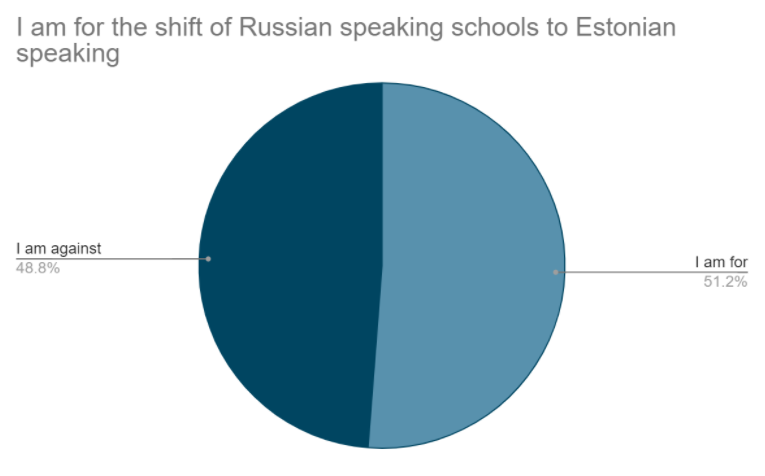

Let’s discuss only the most controversial ones. One of my poll questions was “I am for the shift of Russian speaking schools to Estonian speaking ones” with possible answers of “I am for” and “I am against” (See Picture 3). As we can see in the pie chart, both sides of the barricades have similar percentages.

Picture 3: the first question of the peer voting

Some examples of those in favor

“I am against it because everybody has a right to education. If a person was born in the Russian community, and their parents did not worry about the Estonian aspect of childhood, it is, obviously, tough. I am for the shift to deep learning of Estonian starting from elementary school.”

“This can be beneficial to those who see their future inside of the borders, however, the opportunity of choosing in what language to study must be given to the linguistic minorities. Everyone must understand what problems they can face in the future without a sufficient understanding of the national language, though taking away the opportunity to choose is, at least, not ethical.”

“I am for spending time on studying at the university on my subject but not only for trying to understand the language structures and translating up to 50 words in one lecture. To be competing with those who didn’t spend time on that, at the same level. I believe this can minimize discrimination, and make society less divided because Russian would be integrated into the language, culture and mentality...”

These people see the shift as an opportunity, not as a challenge. They understand how the possible nearby future could look like and what we need to undertake in order to be ready to face consequences. Unfortunately, that’s the reality of Estonia today: you either fight hard or lose.

Some examples of those against

“I am for the study of people's native language. How come is it possible to make kids study in a foreign language from scratch? Just by closing all the Russian schools. I think it cannot be right.”

“We need to leave the opportunity for Russian speaking kids to get the basic education (9 grades) in their native language, and afterwards switch to Estonian when the language proficiency would be sufficient.”

“And this whole process [switching to the Estonian language of instruction] must be very careful and must take some time because we cannot just throw away teachers from 50 Russian schools just because they cannot teach in Estonian. In addition, we don’t have the appropriate amount of teachers prepared to teach in Estonian.”

“50-50. It would be ideal if Russian schools still got to exist, but the studying of Estonian would be deeper. Kids must have some practice to let them understand why they need to learn the language. At the same time, they have to have an opportunity to learn their native language, and in the future, it can benefit them a lot. There are a lot of working places where it is necessary to know Estonian as well as Russian, at least spoken.”

Picture 4: Teachers on strike in Tallinn, 2012

As we can tell, these people somewhat also agree with the shift, although they see a lot of obstacles and corresponding issues with the possible upcoming dramatic change. The then occurring language barrier between new rules and skills of Russian speaking schools would rise as one of the main problems. In order to be allowed to teach in schools, you need to have a language certificate of a certain proficiency, nevertheless, quite a bunch of schools make you really use the language on several specific occasions, as their subjects are still being taught in Russian. With this, we come closer to the next question of my poll.

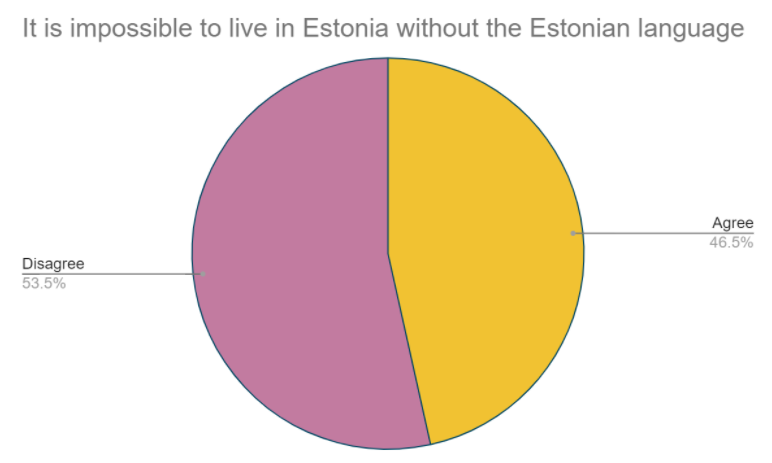

The second question concerns the statement “It is impossible to live in Estonia without the Estonian language”, where the majority agreed on it being quite possible (See Picture 5). I want to highlight one of the messages I got regarding this question. One of my acquaintances has answered: “Qualitatively - no, just exist - yes” meaning that it is possible to live in Estonia with a low proficiency level but not in the perfect conditions. One of the examples is understanding the employment contract, obviously, always written only in Estonian.

Picture 5: the second question of the peer voting

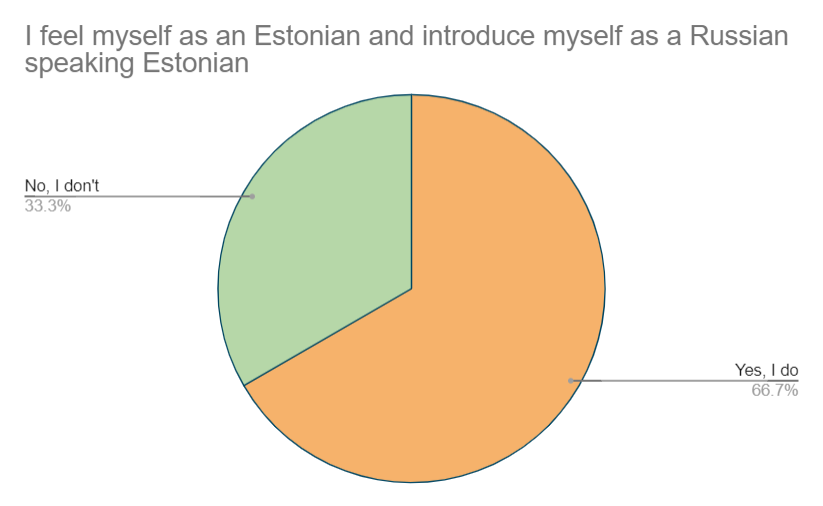

Coming up to the most controversial and the last question I want to include in the discussion. The statement was “I feel myself as an Estonian and introduce myself as a Russian speaking Estonian” (See Picture 6).

Picture 6: the third question of the peer voting

If speaking about me, that’s the exact term I use to describe my ethnicity: there’s nothing else Russian in me other than the native language and partially culture. For instance, for foreigners the situation that a person has a Russian nationality but Estonian citizenship is weird, but it is more than common for us. Going back to the poll, two-thirds of the whole number of answers stated that people do call themselves “Russian speaking Estonians”. One of the answers I got, explained an intriguing position on this statement: “I feel as an ‘Estonianized’ Russian, culturally neither Estonian nor Russian”. We do live in a state of uneasiness and misunderstanding when you cannot tell who you are. You are not Estonian, as you speak Russian, celebrate some of the Russian holidays, read Russian poets and watch Russian YouTube. And you are not Russian, as you celebrate the Estonian holidays as well, watch Estonian films and read Estonian news. If not the one, then the other, but what if both do not suit you?

Tags and the ‘hatred’ between the two communities

The most popular ‘name’ that Estonian speaking Estonians gave to the Russian speaking part of the citizens is ‘sibul’ which is translated to English as ‘onion’. Nobody can tell for sure how this had started, what was the reason for such a weird vegetable name, although there are some assumptions. According to one Estonian Internet forum, the original name dozens of years ago came from the onion-shaped domes on top of the churches all over Russia (Buduaar, 2014). Others say that in the 1990s Russian speakers used to sell a lot of homegrown green onions from the origin nearby the Peipsi lake, as there were massive cultivated areas. Customers of that time pointed out the special sweet taste of that exact type of onions. If in the 1990s this name had no significant inappropriate meaning, in Estonia of the 21st century it is considered as outdated as quite offensive tags on the whole culture. If during the argument between an Estonian speaker and a Russian speaker the one would call the other ‘sibul’, a Russian speaker would probably be either quite insulted or would to start a physical fight. So I tell you it once and would never repeat again - think twice before coming to Estonia and shouting ‘sibulad’ on the streets.

It has been ages but still, Russian speaking Estonians and Estonian Speaking Estonians are different people. Normally we live in peace, but, as you all know, kids on the Internet are evil as they believe that they are hiding their identities online behind nicknames. Cyberbullying is a big problem in every country and Estonia is no exception. One of my Russian speaking acquaintances posted a TikTok on this topic, which attracted a lot of attention and hate to her profile.

Picture 7: TikTok about the Russian speaking culture in Estonia

This TikTok (See Picture 7) demonstrates that some Internet users still like to express their distaste towards Russian speakers. In the video, they called her ‘sibul’, which we talked already about, and screamed “tõmba nahhuj” (English: ‘get the f*** outta here’), “kuradi russ” (English: ‘f*****g Russian) and “tagasi Venemaale” (English: ‘go back to Russia’). Even though all these comments show a lot of anger you cannot hear them on the streets, thankfully.

The real picture

Looking at the situation nowadays I would say that the big fight between Russian speaking Estonians and Estonian Speaking Estonians has almost disappeared. The only people that are still arguing about who is better and whose country Estonia is, are drunk, mostly, men in pubs at 2 am. Young adults respect each other no matter what nationality they belong to or what language they speak. We work at the same places, go to the same supermarkets, bars, clubs, etc. Estonian speakers love Soviet movies and old Russian poetry, Russian speakers listen to modern Estonian rap and laugh at one of the most popular children's books “Kaka ja Kevad” (English: Poop and Spring) by Andrus Kivirähk and so on. We are different but we also are the same.

Nevertheless, the national language still remains Estonian, and we do speak it, better or worse - the problem is yours. Even if Estonian speaking citizens have a bit of a privilege, the choice to compete at the same level is yours, and you will not be judged if you prefer a lower status job position. So I would conclude by saying that as long as you want to scream at somebody you would find a reason for it, even if the problem doesn’t really exist on such scales.

References

Beschactnyi, V. (2021, October 6). Жаркие дебаты о русской школе: закроем гимназии, центристы не отвечают за слова, реформисты и шизофр. . . Delfi RUS.

Buduaari foorum - Venelased. (2014). Buduaar Foorum.

Eesti Piiri- ja Valveamet. (2021). What is it? - Alien’s passport for an adult. Police and Border Guard Board.

Eesti.ee. (2021). Eesti.ee.

H. (2021, October 17). TikTok by @homosexualbat0 [Video]. TikTok.

Hoffmann, T., Makarychev, A. (2017). Russian Speakers in Estonia: Legal, (Bio)Political and Security Insights. In: Makarychev, A., Yatsyk, A. (eds) Borders in the Baltic Sea Region. Palgrave, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-352-00014-6_7

Jašina-Schäfer, A., & Cheskin, A. (2019). Horizontal citizenship in Estonia: Russian speakers in the borderland city of Narva. Citizenship Studies, 24(1): 93–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2019.1691150

Koval, I. (2019, May 26). Narva: The EU’s “Russian” city. DW.COM.

Rahvaarv | Statistikaamet. (2021). Stat.ee.

RV0222U: RAHVASTIK SOO, RAHVUSE JA MAAKONNA JÄRGI, 1. JAANUAR. HALDUSJAOTUS SEISUGA 01.01.2018. (01.01.2018). [Dataset].

Siim, J. (2021, September). Cool Facts about Estonia. Visitestonia.Com.

Sildvee, H. (2017). Estonia and its Russian speakers: Normative framework vs. reality. Tallinn University of Technology.

Tallinna Statistika. (01.01.2021). [Dataset].

Valitsuse moodustamise kokkulepe aastateks 2021 - 2023 | Eesti Vabariigi Valitsus. (2021, February). Valitsus.ee.

Новости, ERR. (2020, July 3). В Эстонии проживает менее 70 000 серопаспортников. ERR.