Why do students partake in bilingual education?

While bilingual education in the Netherlands has been a self-declared success story, this article attempts to rather examine why both students and teachers want to be in it. This has been done by visiting a high school that offers a bilingual English program.

Bilingual education and globalization

Writing this article as an assignment for a course, given at an English-taught graduate program with peers and professors from all over the world, surely proves that globalization is here and is not going to leave any time soon. Indeed, in the educational sense, globalization is

“the broad economic, technological, and scientific trends that directly affect higher education and are largely inevitable in the contemporary world.” (Altbach, 2016, p.83)

Though, this has not been so until recent times. According to renowned professor Carlos Alberto Torres (2002), education, prior to this development, has always taken place within the national context. He further states that the educational system of a country has been structured in a way that prepares its students to become workers that meet the demands of the national economy, but are also able to enter the national patrimony. Globalization, however, has distorted this structure. Globalization has altered the composition of our classrooms, due to the influx of students with an immigration background. Globalization has shifted the educational focus from a national to an international one, due to its diffusion of national borders.

Globalization has made educational policy become a global matter.

The Netherlands is no exception to this, as English-taught programs have been offered at the country’s universities, but also tweetalig onderwijs (TTO; bilingual education) at its high schools. This article concerns a case study of a Dutch high school, located in Tilburg, Cobbenhagenlyceum, which offers bilingual education for almost one and a half decade already.

After a visit to the school regarding this matter, the question to be answered in this article concerns why the students, as well as the teachers and management team at Cobbenhagenlyceum, partake in bilingual education. In this article, we will argue that students mostly do this for positive future career prospects, whereas schools see this as a logical follow-up on the former programme of providing immigrant children with a bilingual education.

Documents on Bilingual Education

First of all, what is tweetalig onderwijs exactly? While the literal translation is bilingual education (BE), as mentioned before, it is rather ambiguous what is exactly meant by that. To stay in the Dutch context, according to Driessen (2005), BE used to refer to OETC (Onderwijs in de Eigen Taal en Cultuur; Education in the Own Language and Culture) or mother tongue education (MTE) for the (Dutch-born) children of the many foreign guest workers who moved to the Netherlands to make a living. He adds that such lessons were enacted by the Dutch government during the second half of the previous century.

The rationale behind it was that the guest workers and their families would eventually go back to their countries of origin; and that therefore, their children should be taught in their native language too, next to Dutch. But in the 1980s, the government realized that this return would never happen and that the immigrant groups needed to integrate into the host society (Driessen, 2005). As a result, MTE was put on hold and teaching the Dutch language has been prioritized ever since (Driessen, 2005) through ‘submersion’ or 'assimilation' (Admiraal, Westhoff & de Bot, 2007), which is basically to be thrown into the deep end of a Dutch-speaking classroom. From there on, students with a migration background were expected to learn the language of the host country as well.

Nowadays, bilingual education in the Netherlands refers to tweetalig onderwijs, which entails that students partially immerse themselves into English (Admiraal et al., 2007; de Graaff, 2013). The applied teaching method is known as Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) where English in the Dutch case is, next to being one of the few language subjects to be taught, the language of instruction in at least half of the curriculum, such as history, mathematics, and physical education, as well as the language of communication in the classroom (Admiraal et al., 2007; de Graaff, 2013; Nuffic & European Platform, 2010, 2013; Verspoor, de Bot & Xu, 2015).

Students are mostly in it because of positive future career prospects

Moreover, BE in the Dutch context was originally meant for VWO (Voorbereidend wetenschappelijk onderwijs; pre-university secondary education) students solely; and only during the lower phase of their high school career, as the national final exams are undertaken in Dutch, for which reason the upper phase needs to be in Dutch as well. However, BE has and still is currently expanding to the other levels of Dutch secondary education (HAVO, hoger algemeen voorgezet onderwijs, intermediate secondary education; VMBO,voorbereidend middelbaar beroepsonderwijs, pre-vocational secondary education), as has been reflected in various sources (Culemborgse Courant, 2017; De Stentor, 2018; Eindhovens Dagblad, 2017; Nuffic & European Platform, 2010, 2013).

What’s more, Dronkers (1993) reported that around the same time when the Dutch language and MTE are put first and last respectively, multiple primary and secondary schools were getting their feet wet with English-taught international education, which was also backed by the government. He pointed out though, that this education was not intended for local Dutch children, but rather for those who have a foreign passport, as well as for those who actually have a Dutch passport, but have lived and been to school abroad, or only stay in the Netherlands for a short amount of time. Today, both local and foreign children can attend either international education or bilingual education at a constantly increasing number of Dutch schools.

Bilingual education, a success story

Over the last few decades, the perks of bilingual education have been well documented. Nuffic, the Dutch organization of internationalization in education, and the overarching European Platform (2010, 2013) even declared that tweetalig onderwijs in Dutch schools is ‘a success story’ and further proclaimed:

"Bilingual education is probably the most successful development in the history of the Dutch educational system." (Nuffic & European Platform, 2013)

Besides the accumulating number of educational institutes chipping in TTO and the learned advantage of speaking English at a higher level, students will assume a more international outlook on their future academic and professional careers. This has been done through exchange programs and (additional) subjects that are framed into a global perspective.

Both research conducted inside (Admiraal et al., 2007; Verspoor & Edelenbos, 2009; Verspoor et al., 2015) as well as outside the Netherlands (e.g. Lasagabaster & Sierra, 2009; Lorenzo Casal & Moore, 2005; Ruiz de Zarobe, 2008; Zydatiβ, 2007; all cited in Verspoor et al., 2015) has confirmed the anticipated positive outcomes of BE by using the method of CLIL.

Observations on Bilingual Education

To zoom in on the case study of Cobbenhagenlyceum, their information booklet (2018) and website state that tweetalig onderwijs is offered at their school on both levels of HAVO (since this calendar year) and VWO, where you will learn ‘perfect English and get a wide view onto the world’. Regarding this, Cobbenhagenlyceum also pay extra attention to internationalization, which is done through an international network, a variety of projects dedicated to the English language, and even an annual school trip abroad. This is co-financed by the parents, as they pay an additional €400,- for the TTO program.

Furthermore, the percentage of English-taught subjects is about 70%, which naturally exceeds the 50% that is required. Only the language subjects (Dutch, French, and German) are in Dutch, which is for the sake of learning them effectively. On their website, Cobbenhagenlyceum already answered frequently asked questions on the effectiveness of TTO and debunked any potential harm that it would have, such as whether it would negatively affect the students' transition to the upper phase or the comprehension of the English-taught subjects.

Schools see bilingual education as a logical follow up for previous bilingual education provided to children of immigrant workers in the Netherlands

Moreover, the teachers that partake in BE at the school are either native speakers or have been trained intensively at the Language Center of Radboud University Nijmegen and later on in England, which is to assure the quality of English being used in the classrooms. In addition to the advice they got from their primary school regarding the level of secondary education that would suit them, potential TTO students are also assessed on their motivation for the bilingual program. Altogether, the policies of BE at Cobbenhagenlyceum adhere to the set standards of Nuffic and the European Platform respectively.

In the classrooms of Cobbenhagenlyceum

After arriving with my peers at the school entrance and having reported at the front desk, it felt somewhat surreal and nostalgic to be back at a high school again. We were received by our contact person and had a brief conversation about what our schedule would be: mathematics for 8th graders (grade 2 in the Dutch system), biology for 7th graders (grade 1 or brugklas), O&O (Onderzoeken & Ontwerpen, Research & Design) for 9th graders (grade 3), and a one-hour break before a more in-depth interview with our contact person that would bring our site visit to an end. She has been actively involved in the matter of TTO at Cobbenhagenlyceum since its inception, despite her personal statement of being 'semi-retired'.

Firstly, the math class for the 8th graders. While we were waiting at the door of the classroom, we heard from our contact person that the 8th graders would have to do an exam. Despite the fact that there would not be much to observe, we nevertheless proceeded with it. As the teacher was giving instructions in English on what to do and not to do during the exam, one of the students asked her classmate, also in English, if she could borrow a pen. While the classmate reached out to her with the pen in her hand, the one who asked was (audio)visually startled, as she literally screamed: “Vieze pen!” (“Dirty pen!”)

In addition to this particular example of borrowing a pen, other interactions between students in all classes showed that students would often still speak Dutch to each other for pragmatic reasons. However, the communication between the teacher and the student(s) was in English, which is in line with the standards of TTO at Cobbenhagenlyceum. We also briefly interviewed two girls who were done with the exam before the end of the given time. They turned out to be good friends of each other, and while one lightheartedly indicated that she chose to enroll into TTO for the trips, the other distinctively emphasized her prior motivation to learn English for her future career perspectives. The time for the exam was up, and we moved swiftly to the next class.

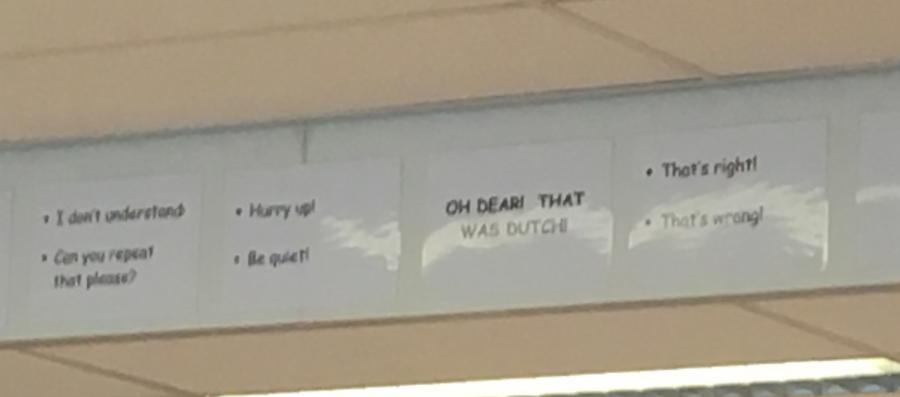

Secondly, the biology class for the 7th graders. Since they had to prepare for an upcoming exam, the teacher suggested three ways to do so: either to join him in going through certain sections to be learned, doing the mock exam, or study with a couple of classmates. Of course, this has caused a variety of interactions that could be reported and analyzed. Especially since it was their first year at TTO, most students were talking in Dutch, as that was easier for them. What is remarkable though, are the signs in the following picture.

The signs depicted in the classroom that 'correct' the students' English.

From what you can see, these signs indicate how to say/ask/reply something in English properly. Moreover, the sign of “OH DEAR! THAT WAS DUTCH!” invokes the assumption that everyone in the classroom should speak English. However, as the teacher is busy with teaching and keeping some students in check, it is easy to ignore this. Hence, some students would speak in Dutch for aforementioned reasons.

The biology class of the 7th graders.

As time passes by, there is this group of three students that were sitting on the right front row in the picture above, who basically functioned as a jammer on the teacher’s radar. Yet, during the conversation between them and the teacher, the topic of why partake into BE suddenly emerged. When the teacher posed them this question, the student at the door bluntly responded: "For the money!"

This was followed by laughter from the jammers. What caught me a little bit off guard though is what one of the other jammers said to the boasting one: "Why learn German? Because others speak German!" It seems that this young student grasped the benefit of being bi- or multilingual, which indirectly shows his motivation for doing BE. And the modern yet very annoying bell rung once more.

Thirdly, the Research & Design class was visited, that was led by the English teacher, who is also the director of TTO at the high school, and another English teacher, who is actually a native of the United Kingdom. After our introductions and the instructions from the teachers, the group split into smaller groups and quickly, one boy made the following remark to his classmates in a joking manner: "Ik weet wat ze gaan opschrijven [I know what they will write down]: Do not speak in English. Do not work."

They are just regular students too, all of whom happen to do the bilingual program. While the two teachers were speaking with each other in Dutch, I went through some groups in order to find why they do TTO. There were answers that we expected, such as to improve their English; to be able to study and/or work overseas; and the trips, but what I did not hear before were the encouragement given by the parents and the extra credentials that a student would get, after completing the program. It should be mentioned though that one of the interviewees in this class was actually a Polish national, who chose the TTO program for practical and financial reasons.

Lastly, the interview with the contact person. She both praised the Polish student for his wit and quick adaptability and the program for accommodating him and the internationalization agenda as well. Besides this, she commented that other staff and herself were motivated to partake in the TTO program, as some teachers are actually from abroad (e.g. French, German, British) who want to teach in English, but also want to let their students become more aware of what plays outside the Netherlands.

Bilingual education as career planning

What has been observed is mostly the proactive attitude and behavior from both the students and the teachers on the matter of bilingual education at Cobbenhagenlyceum and why they do this. Students are mostly in it because of positive future career prospects, whereas schools see bilingual education as a logical follow up for previous bilingual education provided to children of immigrant workers in the Netherlands. Besides the obvious perks that one gains, there are also some external factors, such as the parents that want their children to enroll in a TTO program. This is aligned with the assumptions that Dronkers made more than two decades ago:

"The internationalisation of one sector of education in the Netherlands results from demand by parents and pupils." He continued that the demand for bilingual education originates from "the increased cohesion between the economies of Europe, which give parents and students an international orientation" (Dronkers, 1993, p.304).

To fast-forward, this cohesion not only takes place inside, but also outside the European continent nowadays. This is also somewhat reflected in the motivations of teachers and other staff involved. To them, it is rather an intrinsic, ideological choice to teach in English, which is, next to improving their proficiency, meant to inform young, bright students about what goes around in Europe and the rest of the world.

As a result, an equilibrium has been reached between the demand (i.e. students & parents) and supply (i.e. teachers & school management) for BE at Cobbenhagenlyceum and other Dutch high schools ever since then.

References

Admiraal, W., Westhoff, G., & de Bot, K. (2006). Evaluation of bilingual secondary education in the Netherlands: Students’ language proficiency in English. Educational Research and Evaluation, 12(1), 75-93.

Altbach, P. G. (2016). Global Perspectives on Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Culemborgse Courant (2017, December 28th). ‘Ik vind tto heel leuk en erg leerzaam, ik voel me er thuis!’ [I like TTO very much and very informative, I feel at home!].

2College - Cobbenhagenlyceum (n.d.). Tweetalig Onderwijs (TTO).

de Graaff, R. (2013). Taal om te leren: Didactiek en opbrengsten van tweetalig onderwijs [Language to learn: Didactics and gains of bilingual education] [Oration]. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Utrecht University.

De Stentor (2018, January 25th). Ook havo-leerlingen RSG krijgen tweetalig les [Also havo-students get bilingual classes].

Driessen, G. (2005). From Cure to Curse: The Rise and Fall of Bilingual Education Programs in the Netherlands (pp.77-107). In J. Söhn (Ed.), Arbeitsstelle Interkulle Konflikte und gesellschaftliche Intergration (AKI): The Effectiveness of Bilingual School Programs for Immigrant Children. Berlin: Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung (WZB).

Dronkers, J. (1993). The Causes of Growth of English Education in the Netherlands: Class or Internationalisation? European Journal of Education, 28(3), 295-307.

Eindhovens Dagblad (2017, November 16th). Tweetalige mavo op Jan van Brabant in Helmond [Bilingual mavo at Jan van Brabant in Helmond].

Nuffic, & European Platform (2010). Een duurzame voorsprong: Resultaten van wetenschappelijk onderzoek naar tweetalig onderwijs [A sustainable advantage: Results from scientific research to bilingual education]. Haarlem, the Netherlands: Nuffic & European Platform: Internationalising Education.

Nuffic, & European Platform (2013). Bilingual education in Dutch schools: a success story. Haarlem, the Netherlands: Nuffic & European Platform: Internationalising Education.

Torres, C. A. (2002). Globalization, Education, and Citizenship: Solidarity Versus Markets? American Educational Research Journal, 39(2), 363-378.

Verspoor, M., de Bot, K., & Xu, X. (2015). The effects of English bilingual education in the Netherlands. Journal of Immersion and Content-Based Language Education, 3(1), 4-27.