Transnational identity construction through narrative beginnings in Marjane Satrapi's 'Persepolis'

In a context of peoples in a globalising world, the existence of transnational cultures and identities is inevitable. In order to gain understanding of the construction of such identities, this essay explores Marjane Satrapi’s graphic novel Persepolis. The autobiography tells and mediates the story of Satrapi’s existence in Iran and Europe, an experience which defines her transnational identity. The fact that graphic novels are a "new literary art form [and] comic books are what novels used to be – an accessible, vernacular form with mass appeal" adds to their status as an artistic medium (McGrath, 2004). Persepolis contains simple and striking black-and-white illustrations and textual content whose narrative identifies it as a product of globalisation.

To reveal the notions of transnational identities and leading narrative elements in Persepolis, this essay discusses storytelling, closure and visual emotion in comics and Catherine Romagnolo’s theory of narrative beginnings. This is followed by an investigation of these phenomena and their meaning in Persepolis, analysing themes which focus on the protagonist’s experience such as cultural inequalities, the sense of alienation, existential crises and the meaning of language. This paper aims to answer the research question, how do the graphic novel as a storytelling medium and narrative beginnings function in constructing a transnational identity in Persepolis?

Storytelling in graphic novels

Graphic novels, or comics, contain what Will Eisner identified as sequential art, single images transformed into the art of comics as they are spatially juxtaposed (2008). McCloud further narrows this definition to "juxtaposed pictorial and other images in deliberate sequence, intended to convey information or to produce an aesthetic response in the viewer" (1993, p.9). Comics are identified as an art of story-telling through their ability to portray human experiences either through words or pictures, or a combination in the form of word specific, image specific, duo specific, additive, parallel, montage or interdependent frames.

As these frames are combined into a sequence they can include moment-to-moment, action-to-action, subject-to-subject, scene-to-scene, aspect-to-aspect and non-sequitur sequences. Western style comics tend to be short and include mostly action, subject and scene sequences as they show things happening in concise and efficient ways.

This creates a split with Eastern comics, which are more balanced in including all types of sequences and tend to be longer. Where Western art does not wander much and is goal-oriented, in the East there is a rich tradition of cyclical works of art and the idea of negative space being part of the work as much as the included elements. Such cultural influences, globalisation, fragmentation and rhythm have influenced the comics and style of the West (McCloud, 1993).

As sequences create an overriding identity on all images to consider them as a whole, comics rely on the aspect of closure, the mental completion of that which is incomplete based on past experience. Closure is the agent connecting time, space and motion and applies in the gutter between sequential images, where the reader’s imagination constructs unconnected moments into a continuous reality. The writer provides alchemy to help the reader find meaning in this in-between magic which is unique to comics.

Additionally, the idea that a picture can evoke an emotional or sensual response in the viewer is vital to the art of comics. This is achieved with the principle of symbols as the basis of language, where unique patterns exist as indicators for each emotion or inner state. For example wavy lines as a representation of smoke or craze. Words then function to clarify abstract patterns and shapes, because they have the power to completely describe the invisible realm of senses and emotions, words are specific but may lack the immediate emotional charge of pictures.

Narrative beginnings

Narrative beginnings is a narrative theory which has been extensively researched and applied by intellectual Catherine Romagnolo, mostly in a feminist literary context. In her 2015 book Opening Acts: Narrative Beginnings in Twentieth-Century Feminist Fiction, she provides an outline of the concept. As beginnings play a role in both narrative content and form, Romagnolo distinguishes between conceptual beginnings, which are addressed as concepts within narratives, and formal beginnings, which are the formal features of a new start within a narrative. Beginnings engage on the four interconnected textual levels of theme, discourse, story and plot, which are respectively conceptual beginnings, primary and secondary discursive beginnings, chronological beginnings and causal beginnings.

Conceptual beginnings address how forms and content connect to transfer a thematic focus on beginning and origin. The primary discursive beginnings indicate the beginning of a text, also referred to as openings. As they are part of the discourse and narrative, they are determined by how the story is presented and are not a part of the story itself. A beginning is primary discursive when it introduces the narrative frame and transports the reader into the narrative’s world.

Secondary discursive openings indicate the beginning of a chapter or a break in the text. As they can be considered new beginnings, like a new scene in a play, and exist within primary beginnings, their analysis is intertwined with the reader’s interpretation of the primary opening. Chronological beginnings are the earliest unique moments in the narrative, which Richardson relates to significance, as "a critical shifting until we arrive at the first significant event of the story" (as quoted in Romagnolo, 2015).

Lastly, causal beginnings are part of the plot, describing causally connected series of narrative elements linked to the story. Chronological beginnings directly influence the readers’ interpretation of the plot and thus what they identify as its causal beginning. Causal beginnings also play a role in the interpretive process, as what the reader identifies as the causal beginning of a narrative determines the way in which they read the entire novel and its primary plotline. All beginnings are connected to other textual elements such as temporality, sequence, perspective, endings and middles.

Romagnolo uses this framework to analyse and criticise narratives that contextually use narrative beginnings to destabilize cultural traditions. She attempts to reveal how formal and conceptual beginnings construct knowledge, history and subjectivity and how they function as mechanisms which question the conventional. Writers conceptualising the beginnings in and of their narrative destroy restrictive ideas of collective and individual origins construction and of hierarchal, gendered and racialized ideas of agency.

Beginnings are an undeniable part of the writer’s subjectivity that occurs when they are writing or when the reader is reading, as formal beginnings represent a developing narrative and an authorised subject. Said and Miller have examined how such beginnings invoke notions of origin and claim that one needs to have something present and pre-existing, like sources or authority, on which a new story may be based. "They suggest that formal beginnings cite authoritative cultural norms through repetition, while occluding the way in which subjectivity is formed through exclusion. This citation, this repetition, creates fissures, gaps, and remainders that undermine, deconstruct, if you will, the cohesiveness of beginnings and origins, as well as the subjectivities they help to constitute" (Romagnolo, 2015). Such origins help to establish our status as individuals, our place in collective communities, and our cultural, national, and racial identities.

Conceptual beginnings in Persepolis

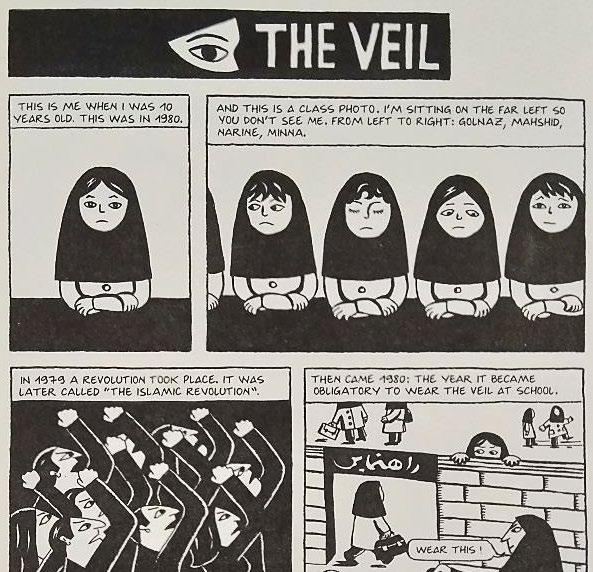

'The Veil' - Persepolis p. 3

The first textual fragment in the novel is an introduction, the sole textual part of the entire story. It is written by adult Marjane as she explains the grim causes of the Iranian revolution. The visual story itself then begins with a chapter named ‘The Veil’ (Satrapi, 2008). This instantly brings the reader into the narrative of the oppressive world of 1980s Iran, which influences the childhood of the protagonist into instability on the one hand, and rebellion on the other. The opening of this narrative is a return to a moment in history and provides a means of exploring the origins of Marji’s rebellion, frustrations with not fitting into society, and her aim to destabilise authority.

The first frames introduce the reader to the narrative forms and frame that are used throughout the novel. The covering narrative is in past tense, from present Marjane’s perspective, and the characters in the novel interact in first-person present narrative. The latter is from the perspective of a child growing into a teenager. This narrative perspective is inevitably connected to beginnings as combined they question the intertwined-ness of identity and narrative point of view.

This perspective represents a new beginning constructed by the language of the narrative. This language is visible in the text, but also in the style of drawing, which are simple and stylised black-and-white illustrations, conveying the dark mood of 1980s Iran. Also, as Marjane identifies with the main character, she is able to recall and convey her past emotions. In the first frame she is unhappily wearing a veil and the gutter between the first two sequential images represents her being cut out of her class photo, which indicates she already had a sense of feeling estranged from her community at that time. Yet with closure the reader can place her within her community.

Persepolis is divided into two parts, the story of a childhood and the story of a return, with its chapters in chronological order and each with its own opening. During the first part of the novel the reader has experienced Marji growing up in the political and religious turmoil of Tehran, where women are punished by the guardians of the revolution and young poor men are sent to war. Marji’s attempts to rebel against the anti-Western regime by using Western artefacts has been explained. She uses them in the way she thinks westerners do, such as wearing jeans and Michael Jackson buttons and listening to Kim Wilde.

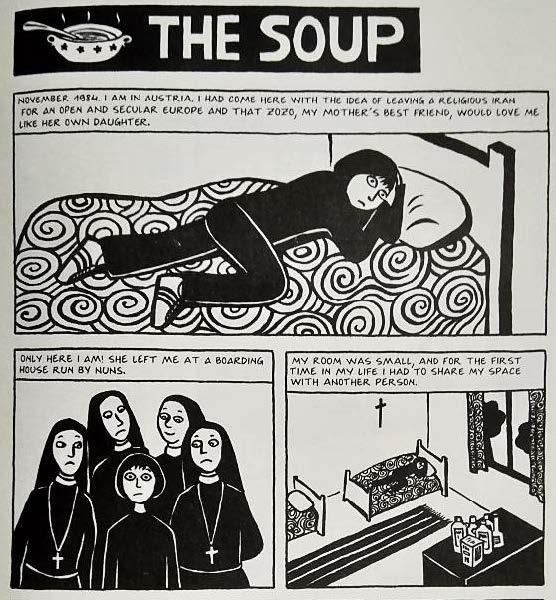

'The Soup' - Persepolis p. 157

In the middle of this first part, the discourse presents an imminent secondary discursive beginning as Marji is sent off to Austria by her parents in an attempt to protect their independent and outspoken daughter. She ends up in a boarding school run by nuns in Vienna. The corresponding chapter ‘The Soup’ presents the opening of this new section, which is loaded as it incites an identity crisis in Marjane.

The opening phrase "November 1984. I am in Austria" signifies the new plot trajectory, entering the crisis of being in the reality of Europe, which is not the Western sphere Marjane expected it to be (Satrapi, 2008). This personal crisis is visualised through the title of the chapter, as well as through Marjane’s body language as she sadly lies on her bed with little physical action in the frame sequence. The wild pattern on her bed is a symbolic indication of her internal chaos and of the impact of this traumatic event, which fragments her cultural identity and her status as an Iranian woman.

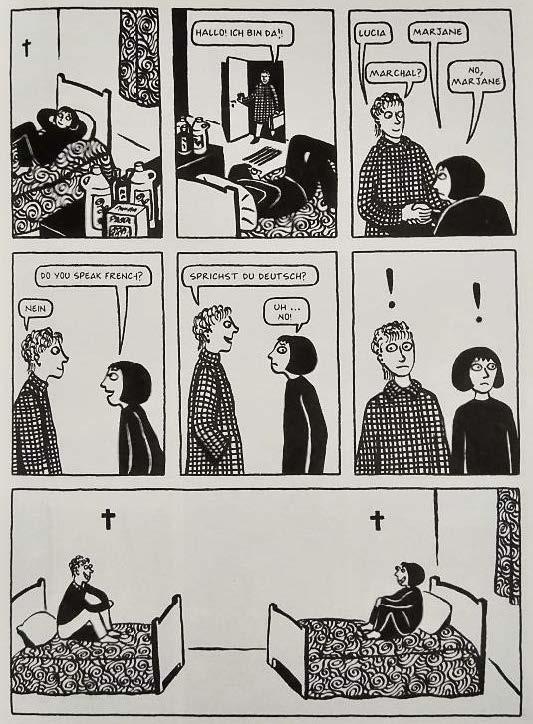

Persepolis p. 163

Another way in which Marjane’s crisis expresses itself is through language and naming. Language has the ability to provide a sense of authenticity and belonging but can simultaneously place a subject outside the boundaries of a collective identity. At first, Marjane is unable to communicate with people she meets in Austria as she is unable to speak German and understand their customs.

This leads to uncomfortable situations, such as when she meets her roommate Lucia. Her discomfort is shown through their lack of conversation, the space between them and their facial expressions (Satrapi, 2008). Yet, at the moment of writing the novel Marjane is able to explain and translate foreign words and concepts, such as the idea of German supermarket Aldi, indicating that over time she has become able to identify herself with non-native Western languages and culture.

With regard to names, as a part of language they are capable of representing subjectivity and beginnings as they linguistically conjure the moment when a subject and their identity comes into existence. Names are symbolic of origins because a surname holds familial, cultural and patriarchal origins and a first name represents the origin of being born. For Marjane, her surname makes her part of a collective, the Satrapi family, the daughter of Iranian radical Marxists. It makes her a representative for her family, and growing up she is keen to follow her parent’s footsteps in demonstrations and anti-regime activities such as parties with Western music and alcohol.

Marjane’s first name is used most often throughout the novel, and provides an indication of identity and social contours in space and time. Whereas she is lovingly called Marji by her parents in Iran, upon arriving in Europe she is addressed as ‘mademoiselle’ by the nuns, as ‘Marchal’ by her new roommate and her Austrian boyfriend uses her full name ‘Marjane’. This shows how her identity is fragmented, as ‘Marji’ does not exist in Europe and she needs to adapt to her new unfamiliar surroundings but struggles to fit in. Only when she returns to her parents in Iran she is called Marji again, but her identity will never be the same as before.

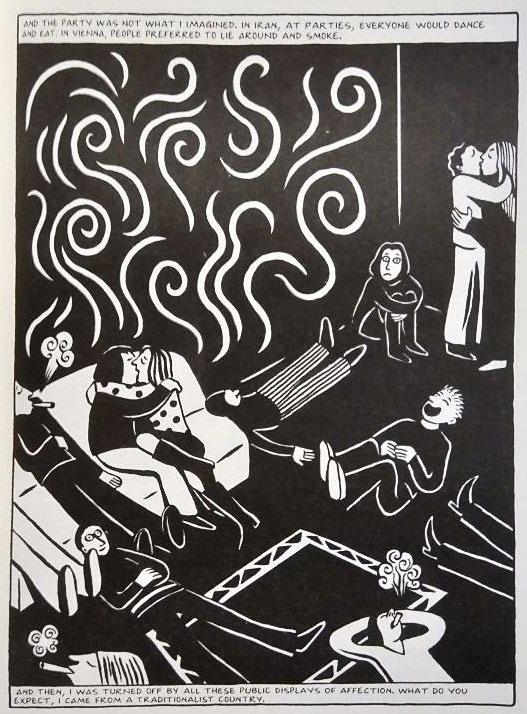

Persepolis p. 187

For Marjane, the longer she exists in the West, the more fragmented and alienated from herself, her surroundings, and her community she becomes. She struggles with the constrictions of her origins and cultural identity, for example when she attends a party and ends up alone in a corner while others get stoned and are sexually active. In this situation her feelings of discomfort and alienation are visualised as a full-page non-sequential dark image, with wild swirls of smoke and fear. Marjane is portrayed as an unhappy creature sitting in the far right corner (Satrapi, 2008).

During these Europe-years she lives with random figures with whom she never finds a connection and keeps moving to new places, Marjane ends up depressed, homeless and sick. She decides to return home to Iran, to her cultural origins, in a search for authentic identity and to internal peace. Marjane’s search for herself carries a deep concern with the causes of a societal breakdown, illuminated by the circumstances of her childhood. She gives up her adolescent freedom to find a solution for her fragmented existence and to find prosperity. In this search for her identity in Iran, she continues with social activism, attends art school and gets married. This appears to be a temporary solution as she soon gets divorced and returns to Europe to live in France to find freedom, closure and repair her inner well-being.

Chronological and Narrative beginnings

The chronological beginning of Persepolis includes the historical origin of the protagonist and a linear narrative structure of her story. As mentioned before, Marjane is a member of the Satrapi family and therefore a part of its royal background, as her great-grandfather was the country’s last emperor. This beginning establishes relationships between events in her history and the developments of individual and cultural identities and status. For example, it explains her and her parents attitude towards Iran’s new regime and their function as a representative collective of Iran, and Marjane as a representative of the West. "This narrative is constantly juxtaposed against seminal events in contemporary Iranian history. Satrapi’s reworking of autobiography as graphic memoir disrupts the categorization of Iranian female identity as one in direct opposition to modern western female identity, positing one as complete suppression by religious authority and the other as the apotheosis of freedom and individualism" (Basu, 2007).

Whereas there are many more examples of themes and beginnings in Persepolis, the analysis above does reveal how the graphic novel and its narrative beginnings function in constructing a transnational identity.

First, the conceptual and primary beginnings set the tone and narrative framework for the entire novel, sketching the scenario and struggles of the protagonist’s childhood during the Iranian revolution, told from her personal perspective. Then, the major secondary discursive opening concerning her exile in Austria creates a contradiction which incites the fragmentation of her identity and loss of sense of cultural origin. Beginnings then provide a platform for these experiences to be expressed through themes such as alienation, language and cultural inequalities.

The use of comics as the medium to visualise such beginnings enhances the sensitive effect. As comics uniquely use the combination of images and words in sequential frames, the writer can visualise any aspect of their story, including invisible emotions and feelings through symbols and patterns. The writer provides meaning to and in-between the images, to which the reader adds closure to connect the space and time within the story, a feature which is also unique to comics. As Persepolis contains many action-to-action sequences and is relatively short, it can be said that Satrapi, as a non-Western author, has opted for a Western style comic, hinting to her current state of identity.

Lastly, this narrative allows Satrapi to question the conventional and open up new contexts to challenge the Western vision of Iranian peoples and customs. She aims to show their equality to the West and to produce legitimation and agency in new forms.

References

Bahrampour, T. (2003). Tempering Rage by Drawing Comics; A Memoir Sketches an Iranian Childhood of Repression and Rebellion.

Basu, L. (2007). Crossing Cultures/ Crossing Genres: The Re-invention of the Graphic Memoir in Persepolis and Persepolis 2.. Nebula: A Journal of Multidisciplinary Scholarship, 4(3).

Eisner, W. (2008). Comics and Sequential Art: Principles and Practices from the Legendary Cartoonist. United States: W. W. Norton & Company.

McCloud, S. (1993). In M. Martin (Ed.), Understanding comics - the invisible art (pp. 138-161). United States of America: HarperCollins Publishers.

McGrath, C. (2004). Not funnies.

Romagnolo, C. (2015). Opening Acts: Narrative Beginnings in Twentieth-Century Feminist Fiction. United States: UNP - Nebraska.

Satrapi, M. (2008). Persepolis. London, Great Britain: Vintage.