‘Ukiyo-e’ Woodblock Prints – Modern Appeal through Beauty Aesthetics and The Sublime

Japanese woodblock prints have become some of the most influential illustrations of all time. The prints are well-recognized for their use of pastel and deep colors, as well as their bold, flat-line stylization. The genre is referred to as ‘ukiyo-e’ (浮世, ‘pictures of the floating/fleeting/transient world’) and was especially popular during Japan’s ‘Edo’ period, in the 17th century, all the way through the 19th century. Throughout this time, artists such as Utagawa Hiroshige, Katsushika Hokusai, Kitagawa Utamaro, and Hishikawa Moronobu were incredibly popular in Japan and later also in the West. ukiyo-e prints are made via the earliest printing method, that of woodblock printing.

Artists would typically be commissioned to illustrate a specific piece, from which a woodblock version would be carved. These carved woodblocks would then be used as large stamps to apply the various layers of paint on paper. With this technique, sometimes upwards of a thousand copies would have been printed of a popular release. (Michener, 1959) This wave of art is regarded as a large contributor to the global interest in art among all social classes. Because of the relatively large number of prints, collecting art was no longer exclusive to the upper class of society, as now the bourgeois, as well as the working class could partake in this activity. (Bell, 2004)

Uyiko-e prints started monochromatic with primarily depictions of ‘Bijin (美人,’ beautiful people’), the majority of which were portraits of women. Further, into the styles’ development, colours became more prevalent, and other subject matters such as folklore, history, flora and fauna, erotica, landscapes, and everyday human activity, became very common. (Kobayashi, 1997) This article will specifically focus on these later iterations of art from the late 18th and early 19th, as these have made the largest impact on contemporary arts and culture.

This paper aims, judgment to explore the potential relationship between Japanese ‘ukiyo-e’ woodblock prints and beauty and the sublime. Beauty is a difficult term to define, but within this context, the term will generally refer to the recognized quality of something, the ‘favorable aesthetic judgment’, which gives the viewer a pleasurable response. (Prettejohn, 2005) The sublime can broadly be defined as a paradoxical response towards a certain overwhelming experience, where on the one hand you feel powerlessness and submissive, while also creating an indescribable feeling of high-spiritedness. (Shaw, 2006, p. 2)

To highlight this relationship, three main subjects will be analyzed regarding Japanese ‘ukiyo-e' woodblock prints. Firstly, an analysis will be laid down about ukiyo-e impact on art history and popular culture. This will be illustrated with examples and will lead to a discussion about why this modern appeal of Ukiyo-e’s is related to beauty and the sublime. Thus secondly, an analysis of the Ukiyo-e genre in regards to ‘beauty’ will be brought up.

This will be examined through the work of Prettejohn, who highlights theories regarding beauty aesthetics. This section will also include a critical reflection on Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’. Lastly, the main research goal of this paper is to illustrate why ukiyo-e art can be considered sublime. For this, several theories on the sublime will be discussed, as well as more thorough coverage of the genre’s themes and historical context. Lastly, please note that this research paper has been altered and cut short to make it fit for this publication.

Figure 1: ‘The Great Wave off Kanagawa’ by Hokusai (1831) is the most recognized Ukiyo-e ever created. This is one of the highest resolution scans by the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Ukiyo-e Impact on Global Art History & Popular Culture

The wave of Japanese woodblock prints emerging in the 19th century has had a long and lasting impact on art history and also shows its influence on popular culture. During the start of the Edo period, ukiyo-e were all but exclusively appreciated within Japan itself. However, as the art style developed and progressed throughout the 1800’s, it already became well-loved among European artists and art collectors.

Up until the 1850’s, The Netherlands had a monopoly of trade with Japan, so many woodblocks were accessible in Western Europe. This trade connection became so influential to the point that many Japanese artists were directly commissioned by European art dealers. (Bell, 2004) After the 1850’s, Japan opened up trade again with the rest of the world and thus ukiyo-e also reached the United States. This introduction to the West came at a good time for ukiyo-e artists, as in Japan it had been a mass medium for centuries and it started to lose public interest. (Salter, 2002)

From this, a dealing/collecting scene emerged across Western Europe and the United States. While initially art collectors and artists were not impressed by the woodblock art, the landscape, flora-and-fauna and everyday activity depictions of Hokusai and Hiroshige became increasingly popular. In the latter half of the 1850s, ukiyo-e made their first big impact on art history outside of Japan, as they were a direct sphere of influence to Impressionist painters such as Claude Monet and Edgar Degas. (Mansfield, 2009)

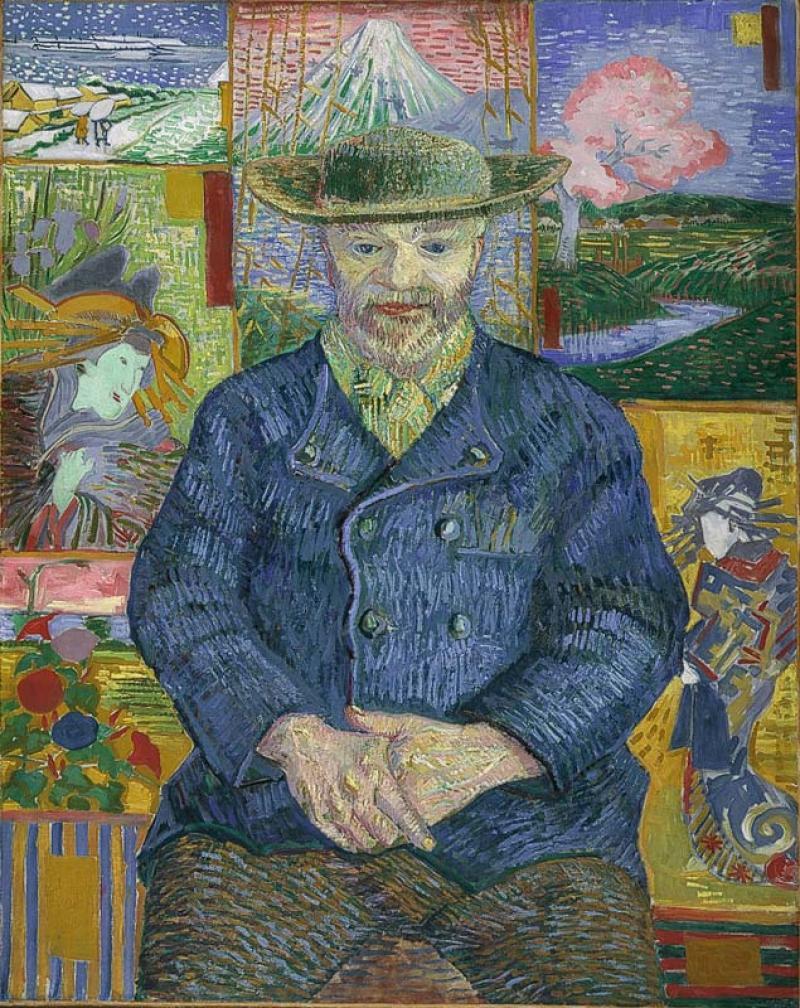

Later the prints would also be inspiring to Post-Impressionists, with Vincent Van Gogh’s admiration for ukiyo-e being particularly well-documented. (Van Gogh Museum, 2022) These artists were largely inspired by the vivid colours displayed in the woodblock prints, as well as their flat shading and perspectives. This influence and near-obsession of Japanese art in the West is often referred to as ‘Japonisme’ (Thomson, 2014)

Figure 2: Van Gogh’s ‘Portrait of Père Tanguy’ (1887) features Ukiyo-e prints in the background by Hiroshige, Hokusai and Eisen.

Woodblock art found new developments in the 20th century in Japan itself, leading to ‘Shin-hanga (新版画, ‘new prints’), which were inspired in turn by Western Impressionism, and Sōsaku-hanga (創作版画, ‘creative prints’), which was a style of woodblock printing where both the illustrating, woodcutting and printing was done by a single artist. (McKenna, 2022)

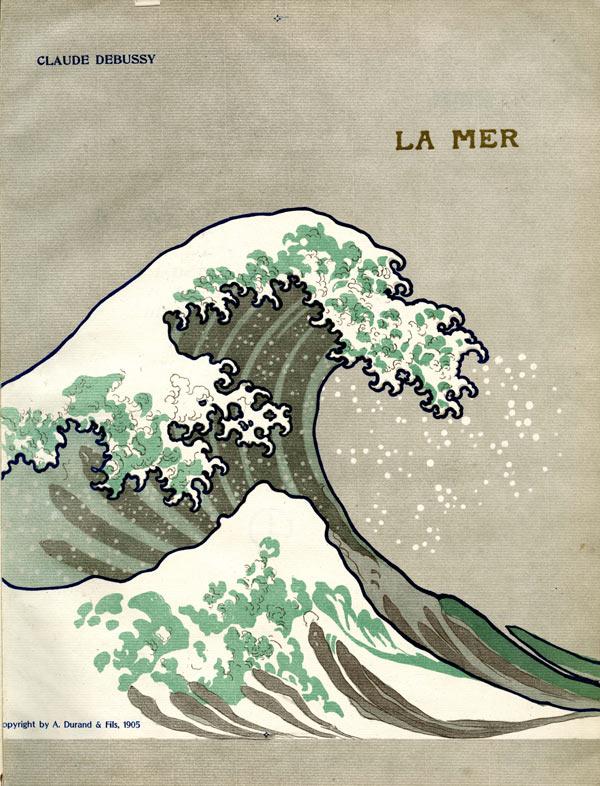

Ukiyo-e also made an impact outside of the visual art sphere. Most notably, classical Impressionist composer Claude Debussy used Hokusai’s ‘Great Wave’ as the cover of his orchestra ‘La Mer’ in 1905.

Figure 3: Cover poster for ‘La Mer’ by Debussy (1905)

Fast forward to our modern times, the influence of Japanese woodblock art remains strong. Speaking of the famous ‘Great Wave’ painting, it is considered to be one of the most reproduced and remixed illustrations of all time. (Wood, 2017) This is likely also attributed to most ukiyo-e non-existent copyright laws. Japan did not implement regular copyright rules at the time, and most artists who did regulate their ownership passed away long enough ago to where their art is now public domain. This makes the works particularly favourable for reiterations. (McCarthy, 2019)

Figure 4, 5 & 6: On the left, ‘Uprisings’ by Kozyndan (2003), perhaps the most famous remix of the Wave. On the top right, a Pokémon card (2021) based on Moronobu’s ‘Beauty looking back’ and bottom right, a vaporwave logo with Mount Fuji in Ukiyo-e style.

While the wave was already one of the most recognized images in the world during the end of the 20th century, the internet age most definitely added another layer to it. Richard Parr, a long-time ukiyo-e collector, highlights the increase in collectors that the online environment brought in his article: ‘How the Internet Changed Japanese Woodblock Print Collecting’. He explains how this increased interest and accessibility of the work of Hokusai and Hiroshige has made the entire scene more popular among a new generation. (Par, 2022)

The popularity of the prints is also reflected in mass consumer culture. Big retail stores such as H&M, Urban Outfitters and Pull & Bear have created entire clothing lines with the most recognizable Japanese woodblock prints. (Urban Outfitters, 2022)

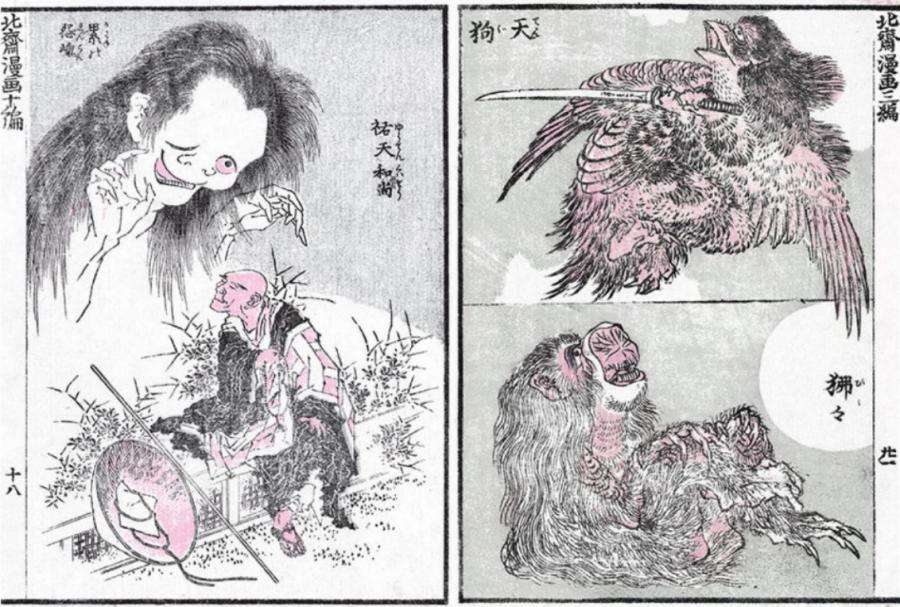

Perhaps most impactful is ukiyo-e direct influence on the immensely popular Japanese ‘manga’ (漫画, ‘whimsical pictures’) and anime genre. The link between these two forms of art can be seen in the line stylization. This influence can be traced back directly to the Edo period with Santō Kyōden's picturebook ‘Shiji no yukikai’ (1798) and Hokusai explicitly calling a series ‘Manga books’ (1814–1834) (Ito, 2014)

In an article by Srđan Tunić about ukiyo-e influence on pop culture he states: ‘Since then, ukiyo-e has become a true part of Japan’s pop-cultural heritage, possibly due to its appeal to a great number of artists from the West, as well as the fact that in this visual and graphic art lie the roots of manga and, consequently, anime.’ (Tunić, 2017)

Figure 7: A page out of Hokusai’s ‘Manga books’ (1814–1834), which inspired contemporary Japanese Manga.

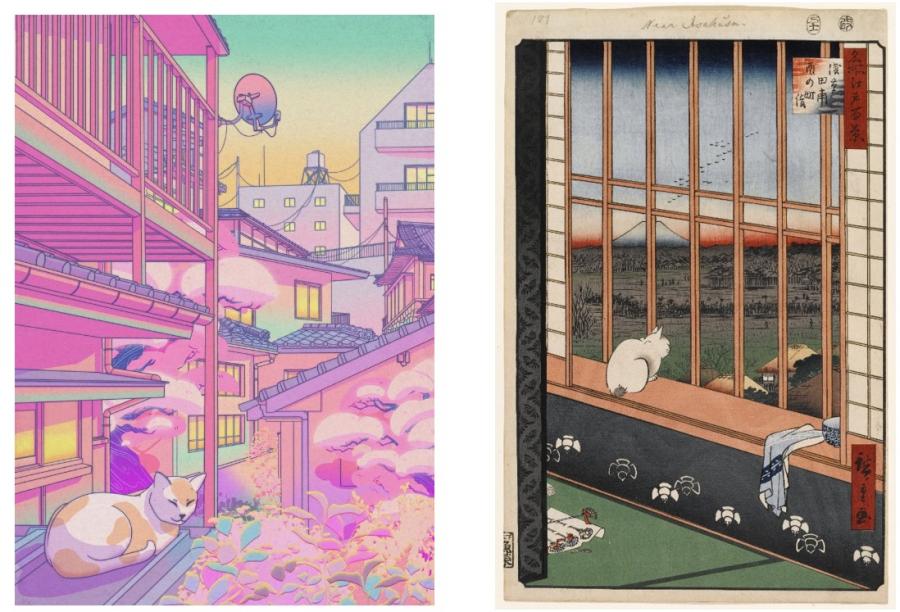

Lastly, the influence of ukiyo-e prints can be drawn even further to the increasingly popular ‘aesthetic lo-fi’ art style, which usually depicts highly stylized manga-esque scenes of everyday activity or city landscapes. Notable are also the stylization of the lines, as well as the heavy use of vivid pastel colours. Elora Pautrat, an environment artist, photographer, and illustrator explains her inspiration for ukiyo-e on her site: ‘Similar to the true meaning behind ukiyo-e: I’m trying to convey through my art, and more especially my illustrations, pictures of a floating, dreamlike world, that brings nostalgia and serenity to people looking at them’ (Pautrat, 2022)

Figure 8 & 9: On the left, Pautrat’s work ‘Nekosaki’ (2021) and on the right, Hiroshige’s ‘Asakusa ricefields and torinomachi festival’ (1857).

Beauty Aesthetics and Form of Ukiyo-e

In Prettejohn’s book titlted ‘Beauty and Art’ there is a chapter about beauty aesthetics called ‘Modernism: Fry and Greenberg’. In this chapter, the views of Fry and Prettejohn herself on beauty are thoroughly discussed. This discussion will now be broadly explained and then applied to ukiyo-e artworks.

According to Fry, beauty is determined when looking at the ‘pure form’ of an artwork. This refers to the intrinsic value of an object: contour, curves, thickness, colour, texture, etc. (Prettejohn, 2005) Fry calls this view on aesthetics the ‘formalist approach’ and believes that anyone can analyse the form of an object on face value. When looking at art through a formalist lens, we are thus able to free ourselves from prejudices and preconceptions. (Prettejohn, 2005)

In David Bell’s book from 2004 called ‘Explaining Ukiyo-e’, he has a chapter about ‘Aesthetic Concepts’. Here, ukiyo-e defining aesthetics are described through its bold, yet highly stylized, linework, flat space composition (typically with one plane of depth), complex patterns, horizontal and vertical flow, object cropping, and asymmetry. (Bell, 2004)

All this is finished with an array of coloured dyes which were uncommon before its time, such as vermilion or lead red, indigo, orpiment yellow, malachite green, and most notably Prussian and ultramarine blue. (Pérez-Arantegui, 2018, p. 98) These colours were often used in contrast to one another to dynamically break up the illustration. All these elements make up the form of ukiyo-e.

Figure 10: ‘Dawn at Futamaigaura’ (1830) by Utagawa Kunisada, the most commercially successful and well-known artist during the Edo period itself. The print captures the form of Ukiyo-e’s well.

Fry’s formalist approach can be used to explain the woodblock prints popularity in popular culture. The prints get used as wallpapers and profile pictures, or thrown on clothing and posters without much context. Thus, Fry would likely argue that it is ukiyo-e intrinsic values that make them popular with a newer generation. It is easy to see their ‘beauty aesthetic appeal’ at face value. (Prettejohn, 2005) This could even be linked to Greenberg’s notion of the ‘consensus of taste’, as contemporary visual culture has guided us back to these vivid colors and lines of the prints, through cartoons, anime, and street art. (Prettejohn, 2005)

However, Prettejohn herself points out the limitations of formalism in her work. As she mentions ‘But we should be philosophically unwise, as well as foolishly self-denying, if we were to stop there. ‘Beauty’ can give us more than ‘art’ and more than ‘formalism’. (Prettejohn, 2005, p. 191)

While ukiyo-e beauty can be described through this formalist lens, this ultimately would be a surface-level observation of the artwork. Bell comments on this as well in his book, in which he says the following about formalism related to ukiyo-e: ’Equally, it fails to explain the relation of ukiyo-e to the complex contexts – social, cultural, literary – in which it was made and employed. In this sense a formalist explanation is unsatisfying – it provides only part of an explanation.’ (Bell, 2004)

Lastly, another interesting clash between beauty aesthetics and ukiyo-e occurs when comparing it to the work of Walter Benjamin’s notion of ‘aura’. Benjamin refers to ‘aura’ as the presence that – so to speak - floats among an art piece. According to Benjamin, an artwork’s ‘presence in time and space’, through cultural and historical context, is what defines its artistic beauty. Therefore, the beauty and authenticity of the art piece is lost through mass reproduction and the ‘flattening’ of the work. (Benjamin, 1935)

A paragraph of his essay ‘The Work of art in the Age of mechanical reproduction’ from 1935 reads: ‘The secular cult of beauty, developed during the Renaissance and prevailing for three centuries, clearly showed that ritualistic basis in its decline and the first deep crisis which befell it. With the advent of the first truly revolutionary means of reproduction, photography, simultaneously with the rise of socialism, art sensed the approaching crisis which has become evident a century later.’ (Benjamin, 1935) With his theories in mind, it can be assumed that Benjamin either believed ukiyo-e was already a victim of the destruction of ‘aura’ in reproduction art, or he was unfamiliar with the prints at the time of his writing.

On the one hand, when following the notion of aura, Japanese woodblock art can not be seen as beautiful and authentic art, since every single print is a reproduction in every sense of the word. The original illustration gets destroyed during the print process. While there were not millions of copies printed like there are today, each print still got hundreds, if not thousands of reproductions. (Bell, 2004)

On the other, Benjamin does clearly state the importance of historical and cultural context when speaking about aura. It could be argued that the printing process of ukiyo-e is precisely what makes them so special compared to other art of the timeframe. Can the creation process of woodblock prints be seen as beautiful on its own? Is it part of the ritual of art? Or was it an early step towards the destruction of authenticity and beauty in art? Moreover, Benjamin also highlights the democratization of art in his essay, since reproductions can make art more accessible to a broader audience. This is an important notion to consider, as Japanese woodblock prints can be seen as one of the earliest democratized forms of art due to its method of distribution. (Benjamin, 1935)

Ukiyo-e and The Sublime – Contextual Themes, Historic Art Culture and Digital Era

When looking at ukiyo-e beauty aesthetics it shows why these woodblock prints are so beautiful to many people. Japanese woodblock art can indeed be considered beautiful, not just because of its aesthetic appearance, but also because of its historical context. But can ukiyo-e artwork also be considered sublime? To put this discussion into perspective, this section will be split into two main categories.

Firstly, when viewing the prints individually, the contextual themes of ukiyo-e pieces might evoke a sublime experience. Secondly, when viewed as collective prints, the historical context behind the artistic cultural scene in which ukiyo-e flourished creates a different perspective on the art. This also might create a sublime experience. All this will also be explained with online digital times in mind.

To recap, the sublime can be defined as a paradoxical response towards a certain overwhelming experience, where on the one hand you feel powerlessness and submissive, while that experience also creates an indescribable feeling of high-spiritedness. (Shaw, 2006, p. 2) The concept is primarily attributed to the basis of Edmund Burke, who believed that beauty in itself was derived from pleasure. At the same time, the sublime comes from uncertainty, pain, and fear, but to some extent also from the serenity and comfortability of this anxiousness. (Burke, 1757)

Throughout time, scholars, intellectuals, and artists have provided different theoretical spectra of the sublime. A few of these perspectives can be applied to themes displayed in ukiyo-e. This includes work such as Julian Bell’s, ‘Contemporary Art and the Sublime’ which relates the sublime to nature artwork, Terry Eagleton’s, ‘States of Sublimity, in Holy Terror’, which relates the sublime to trauma and terror, as well as Hito Steyerl’s, ‘In Defense of the Poor Image’ and Warren Sack’s ‘Network Aesthetics’, which are relevant when experiencing Japanese woodblocks in the digital age.

Ukiyo-e Landscape Art and the Nature Sublime

To start with the most well-known category of ukiyo-e, landscape and nature artwork. Bell relates the sublime to the scale and strength that nature possesses. Landscape paintings can evoke this overwhelming feeling of nature, a sense of powerlessness and acceptance that nature stands above us all. (Bell, 2013)

Van Gogh himself commented on the nature elements of the Japanese art form. In an 1888 letter to his brother, he stated: ‘And we wouldn’t be able to study Japanese art, it seems to me, without becoming much happier and more cheerful, and it makes us return to nature, despite our education and our work in a world of convention.’ (Van Gogh Museum, 2022)

Van Gogh refers to how nature art makes us ‘happier and more cheerful’, which is likely attributed to its bright colours and often peaceful settings. Japanese landscape art however is also able to evoke different feelings. The sublime can be applied to two types of nature illustrations.

Firstly is the seemingly peaceful art piece, with its vivid colours and beautiful setting. These aesthetics pull us into the painting, but upon closer inspection, nature might be challenging or consuming our fragile human lives. A good example of this is ‘The Great Wave’ by Hokusai itself, since on the surface it is a beautifully aesthetic picture, but in reality, it depicts 3 boats, each with about 10 passengers, that get swallowed by an immense wave of the sea.

These seemingly peaceful landscape artworks are often accompanied by people doing ordinary things such as field labour or traveling. This illustrates the contrast well with the large scale of nature, and the small simplicity of a human life. An example of this is Hokusai’s ‘The Suspension Bridge Between Hida and Etchu’, where the scenery depicts a beautiful clear sky and a vast rocky mountain landscape, with a suspension bridge above a mountain abyss. While the setting seems serene, the bridge is weighed down by the two passengers and it looks like it is about to snap in two. This creates tension in the image and can create a subliminal feeling.

Figure 11: ‘The Suspension Bridge Between Hida and Etchu’, by Hokusai (c. 1930).

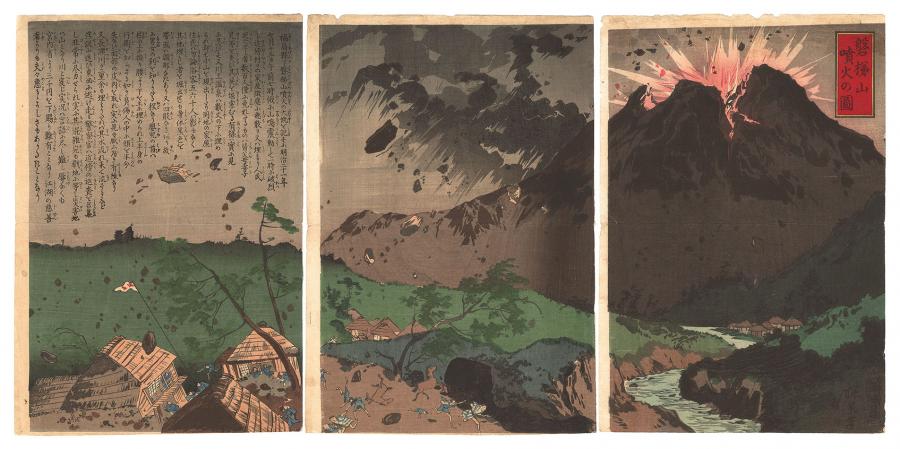

Secondly, some ukiyo-e prints also depict nature as effortlessly ruthless and powerful, through illustrations that use darker colours, display the true effects of destruction, and are based on real events. An example of such a print is ‘Eruption of Mount Bandai’ by Tankai. The prints depict the actual 1888 eruption of the volcano, from which 477 faced death and hundreds remained without homes.

The illustration depicts this terror event, with an exploding volcano, rocks falling, trees and houses destroyed, and people running in fear. The piece is printed in three different panels to depict the scale of the event. (Fujiarts, 2022) This is an example of how nature in art can be expressed through its sheer force, capable of destroying life in an instant. This overwhelming art experience can be considered sublime.

Figure 12: ‘Eruption of Mount Bandai’ by Inoue ‘Tankai’ Yasuji. (1888)

Ukiyo-e Folklore Art and the Terror Sublime

Japanese woodblock art can also be related to the terror sublime that Terry Eagleton describes. In his work, Eagleton describes the sublime as overwhelming, boundless, traumatic, perilous, and tarrying. He says: ‘The sublime thus involves a rhythm of death and resurrection, as we suffer a radical loss of identity only to have that selfhood more richly restored to us.’ (Eagleton, 2015, p. 2) Here he compares this relationship between trauma, horror, and death to the sublime, as this suffering could create a sublime experience of terror. (Eagleton, 2015)

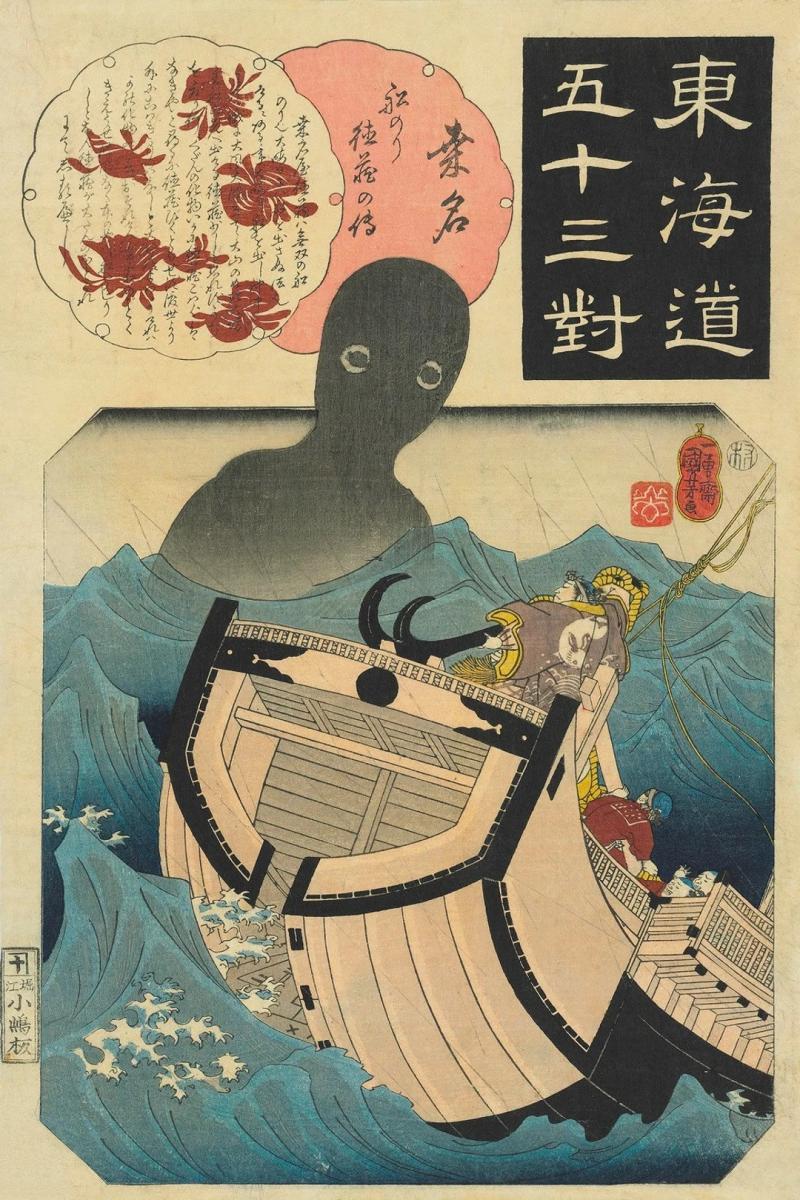

When looking at ukiyo-e art, the ‘terror sublime’ can be related to folklore artwork, depicting ‘Yōkai’ (妖怪, "strange apparition"), Japanese mythological spirits. Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1798–1861) has made illustrations that capture the horror essence of some of these mythological tales, two of which will be highlighted. First, there is the ‘Sea Monk’, a print that represents the story of the ‘Umibōzu’, an ocean-dwelling spirit.

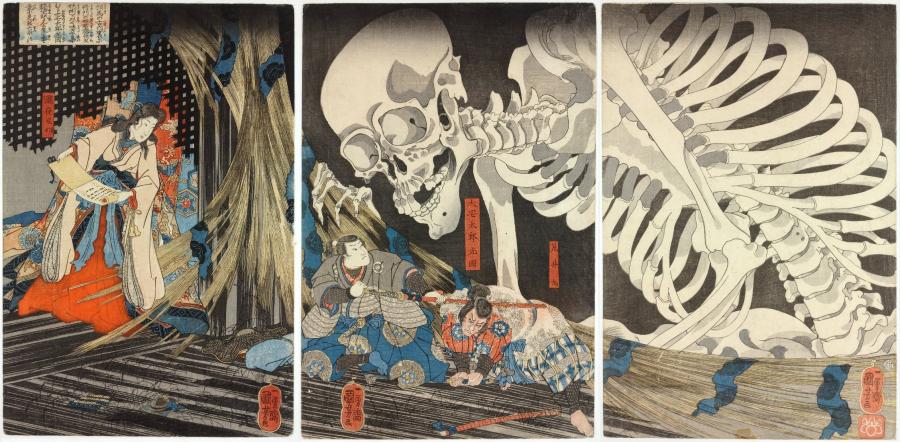

The spirit goes to sailors during a calm sea and then reveals its large bald shadow-like head from underneath the ocean, and aims to break/sink the ship. (Nakau, 2020) Secondly, there is the three-piece print of ‘Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre’, which depicts the semi-historical and mythical scene of the ghosts of rebellion soldiers coming together in one giant skeleton to overthrow their corrupt Emperor. (Gorea et al, 2019)

Figure 13: ‘Sea Monk’ by Utagawa Kuniyoshi. (1845)

Prints depicting these terrifying events from mythological tales can be applied to Eagleton’s description of the sublime. There are also historical tales depicted in ukiyo-e artwork that feature terror and death, such as the many prints depicting samurai fights or ‘seppuku’ (切腹, ‘cutting [the] belly’), a ritual suicide that samurai performed. (Wanczura, 2005)

The original paper highlighted a section about ‘shunga’ (春画, obscene pictures), the erotic illustrations, but this has been cut from this magazine publication. Shunga was a prominent genre, and most ukiyo-e artists took part in it. For this paper, some of the most disturbing shunga prints were analyzed to the sublime, which featured beastiality, rape, necrophilia, and even sex with spirits.

Figure 14: ‘Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre’ by Kuniyoshi. (ca. 1844)

Ukiyo-e Historical Art Culture & Access in the Digital Age

Thus far, only these individual themes have been discussed of ukiyo-e to the sublime. However, perhaps the genre’s most defining feature is the scene it emerged from. The ukiyo-e era was a wave of art in every sense. For multiple decades the style developed and flourished. This resulted in dedicated ukiyo-e art schools, such as the Utagawa school, which spawned countless artists, all drawing in their distinct yet consistent ukiyo-e style. (Bell, 2004) Artists created entire series of specific art themes, such as Hokusai’s ‘Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji’, Hiroshige’s ‘One Hundred Famous Views of Edo’, or even Yoshitoshi’s ‘Twenty-eight famous murders with Verse’. Furthermore, ukiyo-e artists made print books and even frequently collaborated. (Kobayashi 1997)

On top of that, there was an entire culture surrounding the creation process of the prints. While the form can be considered one of the first instances of mass commercializing block roles art, the craft is undeniably special and artistic in its essence. ukiyo-e prints were a collaboration between the artists, who provided the design, the woodcarvers, who prepared the printing block, the printers, who made the impressions on paper with dyes and the publisher, who provided the funds and promoted the print. (Salter, 2002) All of these roles were fulfilled with a high amount of training and expertise.

As the culture grew, there came dedicated ukiyo-e dealers and collectors, long before it ever became relevant in the West. When uncovering eukiyo-e historical context, each print becomes even more interesting. To think so much work went into a single print can be overwhelming. Let alone imagine how the scene might have truly been when reading about its impact on the period itself.

In that sense, ukiyo-e prints are best viewed as a collective wave of art and can be appreciated the most as compilations of artists, themes, and collections. After ukiyo-e have piqued your interest it can become overwhelming to dedicate your focus to the abundance of these elements, but ultimately you will be left with a satisfying feeling of artistic consumption. This can be related to the artistic sublime.

Figure 21: Woodblock cutting is done with utmost precision, as the image needs to be cut in reverse in order to get the print the right side up. (Koyama-Richard, 2014)

Moreover, it can be argued that the digital era has enhanced this sublimity of ukiyo-e art. In Sack’s ‘Network Aesthetics’, he mentions the relationship between the sublime and online-digital databases. With so much data and information at our fingertips in the digital era, it can be overwhelming to navigate through it all, and the same can be said for ukiyo-e art. (Sack, 2007) Though as paradoxical as the sublime is, when getting passed that overwhelming impression, we can access and view more ukiyo-e art than ever before. Whereas it was difficult to see every piece in a collection in the 19th century, it can now be done online via large archives of ukiyo-e art. (Par, 2021)

A similar effect of sublimity can be attributed to the picture quality of the prints online. Steyerl talks about the ‘Poor Image’ in her work, and how the internet has created a digital poorly reserved copy of the original image (of for instance an artwork), which has been compressed to a terrible resolution, altered, and left without a context or source. (Steyerl, 2009) While there are most certainly poor-quality-high-resolution images of woodblock art, the genre has also benefited from the opposite: beautiful high-resolutionhigh-resolution scans.

People such as woodblock printer David Bull have created high-definition images of their collections and put them online for display in databases such as Mokuhankan. These rich images of ukiyo-e can reveal new details and insights into the prints. Most prints are quite small, roughly 38cm x 25cm, and faded due to their age. These high resolution scans can provide perspectives with more vivid colours, refined lines, and zoomed-in shots. This contradicting nature can also contribute to the sublime in the digital age.

Figure 22: An exposition of Japanese woodblock art, which puts into perspective the size of these prints. (The Japan Ukiyo-E Museum)

Conclusion

In this paper, various dimensions of the Japanese ukiyo-e art genre have been discussed. This included its impact on art history and popular culture, its beauty aesthetic, and its potential relation to sublimity. The latter – this relationship of the sublime – was the main highlight of this article, as through these different topics, ukiyo-e might be considered sublime.

Starting off, its impact on art history is undeniable, as it developed Japanese art for more than two centuries and had a large influence on Western Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. This influence continued into our modern times, as ukiyo-e art is highly relevant in popular culture. Some ukiyo-e prints are some of the most remixed artworks of all time, inspired by the immensely popular manga art style and more recently the ‘lo-fi aesthetic’ art. To understand why this impact on contemporary culture remains strong, an analysis was made of the beauty aesthetics of Japanese woodblock art.

And thus, through the work of Prettejohn and her commentary on Fry, the prints were analysed through a formalist lens. This highlighted its bold lines, vivid colours, and unique composition among others. Formalism is not the only way to look at ukiyo-e beauty, however, though it may explain the surface level of interest and appeal that the genre has on a younger generation. Though with the work of Benjamin and his notion of aura, the prints seemed to fall outside of his notion of beautiful, the paper dove into theories of the sublime to cover this longevity of ukiyo-e prints.

Lastly, the Japanese prints were viewed through the perspectives of the sublime. Landscape art was related to the nature sublime by Bell, which brought out that subliminal feeling of the vastness and destructive aspect of nature, relating to the fragility of humanity. Furthermore, folklore and erotic art were related to the terror sublime of Eagleton, which related to the sublime horror aspects and how emotions of anger, confusion, and disgust can be applied to shunga. To close off, this paper covered how the sublime can be related to the grander scope of ukiyo-e historical artistic scene, diving into the strength of the art as a collective piece and its creation process. This conversation was then extended to our digital times, particularly about how online digital archives of ukiyo-e and poor/rich quality images can bring new perspectives on the artwork, which is also related to the digital sublime.

All in all, this paper brought up multiple arguments about ukiyo-e impact on art history, pop culture, its beauty aesthetics, and the sublime. Through all these dimensions, it can be concluded that - at the very least - a relationship between the sublime and ukiyo-e art is certainly possible. A sublime experience is of course highly personal, but there is enough thematic and historical context that Japanese woodblock art carries with them, to the point that anyone would be able to see the sublimity in the art from the specific angle they draw to the most. Ultimately, these images of the floating world seem to be floating in a constant circle around us, as their impact remains relevant even 400 years later, and that realization might even be considered sublime on its own.

References

Bell, D. (2004). Ukiyo-e Explained. Global Oriental.

Bell J. (2013, January) ‘Contemporary Art and the Sublime’, in Nigel Llewellyn and Christine Riding (eds.), The Art of the Sublime, Tate Research Publication.

Benjamin, W. (1935). The work of art in the age of mechanical reproduction.

Biron, C. et al. (2020). Colours of the images of the floating world. Non-invasive analyses of Japanese ukiyo-e woodblock prints (18th and 19th centuries) and new contributions to the insight of oriental materials. Microchemical Journal 152.

Burke, E. (1757) A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, Part 1.

Cerelli, F. (2018). Hokusai: beyond the Great Wave. London Journal of Primary Care. Vol. 10, No.4, 128-129.

Christopher, R. (2022). The Emergence of Japanese Woodblock Prints as Avant-Garde

Folks, M. (2019). A Closer Look: Moon of the Lonely House.

Fujiarts. (2022) Original Inoue Yasuji (1864 - 1889) Japanese Woodblock Print The Eruption of Mt. Bandai, 1888.

Gorea, A. & Mayer, J. & Conover, T., (2019) “Exoskeleton”, International Textile and Apparel Association Annual Conference Proceedings 76(1).

Heckmann, C. (2022). What is Ukiyo-e - Artists, Charactersics & Best Examples.

Ito, K. (2014). Manga in Japanese history. In Japanese visual culture (pp. 26-47). Routledge.

Kobayashi, T. (1997). Ukiyo-e: An Introduction to Japanese Woodblock Prints. Kodansha International.

Koyama-Richard, B. (2014). Modern-day Artisans Carry On the ''Ukiyo-e'' Tradition.

Kruijf, M. (2022) Horny Horses and Camels in Shunga Art.

Mansfield, S. (2009). Tokyo A Cultural History. Oxford University Press.

McCarthy, D. (2019). The Great Wave: what Hokusai's masterpiece tells us about museums, copyright and online collections today. Medium.

McKenna, S. (2022). A short history of 'The Great Wave' in pop culture. Acclaim.

Michener, J. A. (1959). Japanese Print: From the Early Masters to the Modern. Charles E. Tuttle Company.

Nakau, E. (2020). Something Wicked from Japan: Ghosts, Demons & Yokai in Ukiyo-e Masterpieces. PIE International.

Par, R. (2021). How the Internet Changed Japanese Woodblock Print Collecting.

Pérez-Arantegui, J. Rupérez, D. Almazán, D. & Díez-de-Pinos, N. (2018). Colours and pigments in late ukiyo-e art works: A preliminary non-invasive study of Japanese woodblock prints to interpret hyperspectral images using in-situ point-by-by diffuse reflectance spectroscopy. Microchemical Journal 139, 94-109.

Prettejohn, E. (2005). Modernism: Fry and Greenberg , in: Beauty and Art, 1750-2000, Oxford University Press, pp. 157-191.

Sack, W. (2007). Network Aesthetics, in: Victoria Vesna, Database Aesthetics: Art in the Age of Information Overflow, University of Minnesota Press, p. 183

Salter, R. (2002). Japanese woodblock printing. University of Hawaii Press.

Screech, T. (1999). Sex and the Floating World: Erotic Images in Japan, 1700–1820. Reaktion Books. Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society , Volume 10 , Issue 3 , November 2000 pp. 433 – 436.

Shaw, P. (2006). The Sublime. Psychology Press.

Thomson, B. (2014). "Japonisme in the Works of Van Gogh, Gauguin, Bernard and Anquetin". In Museum Folkwang (ed.). Monet, Gauguin, Van Gogh… Japanese Inspirations.

Tunić, S. (2017). Ukiyo-e between Pop Art and (Trans) cultural Appropriation: On the Art of Muhamed Kafedžić (Muha). The Journal of Transcultural Studies, 8(1), 259-283.

Steyerl, H. (2009). In Defense of the Poor Image. e-flux Journal. Issue #10

Urban Outfitters. (2022). Ukiyo-e clothing line. Retrieved from: https://www.urbanoutfitters.com/en-gb/search?q=hokusai

Van Gogh Museum. (2022). Ontmoet Vincent. Inspiratie uit Japan.

Volk, A. (2019). Beauty and Violence, Art and War: Some Reflections on the Visual Cultures of Imperial Japan. UC Berkeley.

Wanczura, D. (2005) History of Seppuku & Ukiyo-e. Retrieved from: https://www.artelino.com/articles/seppuku.asp

Wood, P. (2017). "Is this the most reproduced artwork in history?". ABC News.