Barbenheimer: Affirming Stereotypes In Meme Culture

On the 21st of July 2023, two of the most anticipated movies of the year were finally released to the public: Warner Bros Pictures’ “Barbie” and Universal Pictures’ “Oppenheimer”. Despite their vastly different content, the movies quickly became entangled with each other, giving birth to a new cultural phenomenon called “Barbenheimer”.

The strong contrast in subject matter between Barbie – a fantasy comedy – and Oppenheimer – an epic biographical thriller – promoted a comedic response from various internet users who created memes surrounding this contrasting tone. Barbenheimer exceeded initial expectations, “opening to the fourth-biggest box office weekend in history”(Maiorca, 2023).

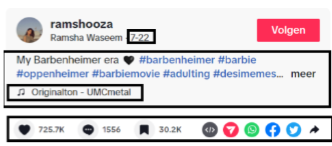

On July 22nd 2023, a video was uploaded onto TikTok that perfectly captures the comedic response to the contrasting tone between the two movies. The video is one of the most-viewed videos regarding #BarbenHeimer, gathering over 16 million views and over 700,000 likes as of December 2023.

The creator is 23-year-old Rashma Waseem, better known as “@ramshooza”, a creator who has gathered over 100,000 followers on TikTok alone. In the popular video, Rashma transitions from wearing pink clothing and make-up as she exits one cinema hall to revealing black clothes and make-up while entering another cinema hall. The accompanying text reads “When You’re Going To Watch Oppenheimer After Barbie.”

Figure 1: screenshot of Ramsha Waseem's TikTok Page (2023) | TikTok: @Rashmooza.

In this paper, a multimodal discourse analysis of the video is presented to show how this “Barbenheimer” video successfully mobilizes stereotypical framings of both movies. It is this delicate multimodal stereotypical narrative that seemingly generates the massive amount of likes.

Multimodality & Indexicality

Studying trends on social media such as TikTok requires a broader scope of the potential formats and sentiments that precede the current ones. Although various concepts and theories can be utilized, I believe that a conceptual framework focusing on multimodality and indexicality will allow us to understand why Rashma’s video in particular obtained so much attention. To understand each concept adequately, it is important to define each term of the framework appropriately and briefly elaborate on its implementation.

To begin, this research will use the notion of multimodality to illustrate the effects of simultaneously utilising several modes visible in the video, such as dialogue, visual change, and music. Multimodal analysis examines many ways of communication, including the semiotic resources used to construct meaning. "Each mode has its specific task and function in the meaning-making process, and usually carries only a part of the message in a multimodal text." (Kress, 2010, page 28) When several means of communication are mixed, they interact and create new meanings that go beyond their original meanings.

In TikTok videos, different varieties of “modalities” can be detected: text, visuals, sounds, facial expressions, etc. According to Jan Blommaert (2020), “the maker of a TikTok video uses multimodal signs to communicate something and perform certain identity”. By attaching multimodality to the conceptual framework, this study will examine how the combination of dialogue, visual transformation, and music respond and expand on each other and their combination allows for new forms of meaning and messages delivered within the video.

Lastly, this study utilizes indexicality, a concept that refers to the normative systems that guide communicative actions. To understand the social meaning of TikTok, the social roles, norms, and identities that are suggested by the different semiotic signs in the video need to be analyzed, something which indexicality is useful for. According to Jan Blommaert (2005), the central idea of indexicality relates to the insight that any communication tool relies on personal beliefs, background, characters, and social contexts.

According to him, indexicality refers to the “meaning that emerges out of text-context relations” (Blommaert, 2005). It suggests that semiotic units always point to more than just their denotational meaning. In TikTok trends – like Barbenheimer – communities of practice emerge, where people express (temporarily) shared patterns of indexical meaning-attributing. The indexical meanings of expression found in the TikTok video not only helped me grasp the meme’s implicit message but also the engagement of viewers. Analyzing these multimodal semiotic units against the backdrop of indexicality therefore provides a comprehensive understanding of the video’s social meaning, including suggested social roles, norms, and identities within the video.

#Barbenheimer: The Multimodal Video

Now that we've created the conceptual foundation for our research, we can concentrate on the movie itself. As seen in Figures 2 and 3, we experience a variety of modalities of communication when interacting with the video. The most noticeable is the video itself, which shows a clear transition from "Barbie" to "Oppenheimer". Another prominent mode is the text Rasma wrote in the video: “When You’re Going To Watch Oppenheimer After Barbie” but also in the caption of the video: “My Barbenheimer Era” with various hashtags, including #Barbenheimer.

The purpose of hashtags is to "enable users to connect their tweets to large thematically linked bodies of tweets" (Blommaert et al., 2019). Ramsha's use of the hashtag #BarbenHeimer indicates her desire to join in the greater conversation surrounding the Barbenheimer phenomenon. Metadata and stats can provide insight into the post's widespread popularity. These numbers - 725.7K likes, 1556 comments, and over 30K saves - are extremely high, suggesting TikTok's widespread appeal and adoption.

Figure 2: Various Modes in the Data. | TikTok: @Rashmooza.

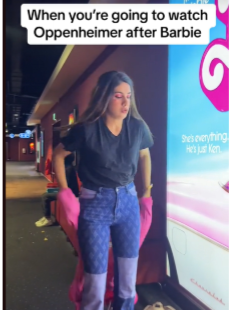

Besides the communication and uptake tools on TikTok, various other mediums/modes were used in the video itself: (1)text, (2) clothing/appearance, facial expressions, choreography and (3) music. It appears that this visual shift from a Barbie viewer to an Oppenheimer viewer is the leading notion within the video, a shift that is empowered and established on various multimodal levels.

By using various modes and letting them expand on each other in the video, Ramsha creates multiple layers of meaning in the video. In the first place, viewers of the video will read the dialogue text box (1) stating “When You’re Going To Watch Oppenheimer After Barbie” at the top of the video. This dialogue adds an explicit verbal element to the multimodal object as the dialogue provides context and commentary on Rashma’s actions depicted in the video, suggesting that there will be a transformation from one movie to another.

The images and choreography (2) follow the text and are next to the multimodal medium. The video graphically elaborates on the textbox as it transitions from a "Barbie viewer" to an "Oppenheimer viewer". Ramsha appears to believe that "Barbie" caters to an audience that enjoys lighter, trivial, and less profound content, as evidenced by a seemingly unserious facial expression, feminine colouring, and not looking directly into the camera, as opposed to a darker masculine colouring, seriously monotone facial expression, and looking directly into the camera.

Contrastingly, it appears that “Oppenheimer” is associated with an audience that is geared to more mature and serious content. Her visual transformation serves as her virtual narrative that indicates that “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” are vastly different in their overall mood, presentation, but also target audience.

It appears that she intended to make this TikTok for a longer time as she made sure to bring everything that could be associated with both “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer”. It is through these visual cues – like clothing, make-up, and facial expressions – that it becomes clear that these semiotic resources carry cultural and symbolic meanings.

Figure 3: Showcasing the contrasting tone of "Barbie" to "Oppenheimer

These visual cues are further elaborated on by the sound utilized in the video (3), the last aspect of the multimodal object. The sound consists of a metal cover of “Barbie Girl” by Aqua, which was uploaded by a user called “@umcmetal”. The music further conveys the contrast between the nature of “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” established by Ramsha. As Ayron Rutan (2022) points out, black is often associated with the metal genre.

By selecting a metal cover of “Barbie Girl”, Ramsha taps into the semiotic resources associated with metal music, particularly its black qualities and she connects it to the “dark” atmosphere of Oppenheimer. The auditory juxtaposition between the cheerful lyrics and melody of “Barbie Girl” and the heavy and aggressive guitar riffs and vocals highlights the shift in the mood and tone that can also be identified in the video. Its strategic use of semiotic resources in the form of music effectively creates another level of contrast and meaning between the natures of “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer”.

Figure 4: Caption Of The Cover. | TikTok: @umcmetal

Unveiling Stereotypes Through Indexicality

Besides multimodality, the concept of indexicality is fundamental to comprehending the implicit message that Ramsha appears to deliver. To examine this, the first focus point will concern the indexical visual message of the video.

It appears that Ramsha’s transformation from a “Barbie” to an “Oppenheimer” viewer embodies the indexical meanings which are related to societal norms and historical stereotypes. Her initial appearance, consisting of pink clothing and colourful make-up, aligns with the stereotypical physical and personality notions of femineity that the Barbie doll exhibited decades ago. In contrast, her transition to black clothing and serious facial expressions appears to align with the traditional physical and personality notions of masculinity.

The visual transformation showcased in the video makes the indexicality evident as it draws upon her own beliefs or perspective regarding gender roles and stereotypes: Barbie is more feminine due to its more colourful aesthetics while Oppenheimer is more masculine due to its darker aesthetics. By using these semiotics, it appears that Ramsha not only reflects her own beliefs, but also taps into broader societal understandings of traditional gender roles and stereotypes. This usage of stereotypes, and the almost “automatic” associations individuals have with them, seemingly allows Ramsha to convey her message effectively and it appears that she attempts to transfer the indexical value of traditional stereotypes onto Oppenheimer and Barbie.

At the auditory level, we can also establish indexicality. Here, Rasham's choice of a metal cover of “Barbie Girl” can be seen as a strategic utilization of semiotics to enhance the contrast between “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer”. As examined, metal music is often associated with darker themes and colours. Her transformation from pink to black aesthetics enhances the audio we hear in the background, as the colourfulness of the original song is removed by the cover – just as we see Rasham remove her colourfulness in clothing.

The audience is key in this interpretation of indexical meaning as they understand that the metal cover is not just a random choice of music, but a deliberate selection to reinforce and elaborate on the narrative in the video. The transition from “Barbie” to “Oppenheimer” is a “darker” one, so black clothing and metal music are more fitting than the colourful clothing and nature of the original song. The selective music choice makes the message more impactful, as it contributes to the audience’s broader understanding of the contrast between “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer.” It leverages the semiotic resources associated with metal music and aligns them with Rashma’s personal beliefs and the societal context surrounding gender roles and stereotypes.

Figure 5: showcasing Rashma’s transformation, embodying both her personal beliefs and societal gender role stereotypes

The Verdict: Affirming Stereotypes

It appears that this particular video succeeded in gaining attention because Ramsha’s depiction of “Barbie” and “Oppenheimer” resonated with people's semiotic expectations. Namely, that “Barbie” is associated with more feminine, colourful and trivial audiences, while Oppenheimer is associated with darker, masculine and serious audiences. By using discourse analysis, it becomes clear that Ramsha’s TikTok effectively utilized both the multimodality of TikTok and the indexicality of semiotics' traditional stereotypical ideas. It appears to showcase the contrast between the overall aesthetics and audiences within the “Barbenheimer” phenomena in a way that attracts attention rapidly.

In her video, Ramsha deploys new semiotic and multimodal resources on TikTok to transfer the indexical value of stereotypes onto both Oppenheimer and Barbie. She takes the historical, sexist social meaning behind traditional stereotypes and seemingly fuses this with her indexical meaning of these stereotypes. In doing so, Rashma constructs a new social meaning to the “Barbenheimer” event.

The phenomenon, as depicted by Ramsha in her video, involves the playful use of traditional stereotypes, appearing to utilize them as a source of humour to elicit comedic effects and responses from the audience. The use of stereotypes in his manner appears to be a conscious choice to create entertainment.

Even though the action of employing these stereotypes might be undertaken without deliberate awareness of its impact, the phenomena playfully contribute to the sustenance of traditional stereotypes within society. By drawing on established cultural norms and expectations related to gender roles or other gender-related social constructs, the "Barbenheimer" case reinforces and perpetuates these tradtional stereotypes in an apparent lighthearted and relateable manner

The extensive uptake the video received could be an indicator that traditional sexist stereotypes remain a massive and popular item within public discourse, meme culture and everyday life. The popularity and comedic response the video achieved appears to showcase the lasting influence of ingrained social stereotypes in our collective memory, and ultimately affirming stereotypes through meme culture.

References

Blommaert, J. M. E. (2005). Discourse: A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert, J., van de Sanden-Szabla, G., Prochazka, O., Maly, I., Kunming, L., & Liu, L. (2019). Online with Garfinkel. Essays on social action in the online-offline nexus. Tilburg Papers In Culture Studies, 229, 82–95.

Bramesco, C. (2023, July 24). Oppenheimer and Barbie share a single clear theme. Polygon.

Burnet, K.(2022, November 7). TikTok’s inverted filter: Debunking symmetry as a beauty standard. Diggit Magazine.

Issues Online. (2023). Gender stereotyping.

Jan Blommaert. (2020, June 23). Jan Blommaert on multimodality [video].

Kachel, S., Steffens, M. C., & Niedlich, C. (2016). Traditional Masculinity and Femininity: Validation of a new scale assessing Gender Roles. Frontiers in Psychology.

Kress, G. (2010). Multimodality: a social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London; New York: Routledge.

Maiocroa, T.(2023, July 27). Who won Barbenheimer? “Barbie” broke box office records, but popularity varied by state. USA TODAY.

Rutan, A. (2023). “What Does Your Favorite Color Say About Your Music Preference?” LoudWire.

UMCmetal [@UMCmetal]. (2021, May 23). “Barbie Girl (Metal Cover by UMC) feat. Bülent Ceylan now online! Check it out!” [video]. TikTok.

Waseem, R. [@ramshooza]. (2022, July 22). “My BarbenHeimer Era 🖤 [video]. TikTok.

What are gender roles and stereotypes? (2023). PlannedParenthood.