Deviance and the furry community

The furry community is a large social group that manifests itself both online and offline. It is focussed on the appreciation of anthropomorphic characters (animals given human qualities) and members have their own "fursona": an anthropomorphic character that represents them, mostly online, but sometimes also offline. This paper will look at how the group is labelled as deviant by non-furries, and how deviance is constructed also within the group itself.

The furry fandom as a social group

“A furry is a fan of media that features animal characters doing “human” things (e.g., walking, talking). Examples of famous anthropomorphic animal characters include Bugs Bunny and Mickey Mouse.” This is the definition of a furry that Furscience, a site dedicated to research on the furry community, gives us.

However, merely being a fan of media that features anthropomorphic characters is not enough. To be a part of a social group, as Howard Becker describes in Outsiders (1963), one must master the norms, the language and the emblems of the group. This is also the case in the furry community. Luckily, there are countless videos (such as this playlist), blogs and chats dedicated to teaching new furries what they need to know.

“Creating a fursona is one of the most universal behaviours in the furry fandom (see 3.8). Defined as anthropomorphic animal representations of the self, furries interact with other members of the fandom through the use of these avatars, both in-person (e.g., badges at conventions) and online (e.g., profile pictures, forum handle)” (Plante et al., 2016).

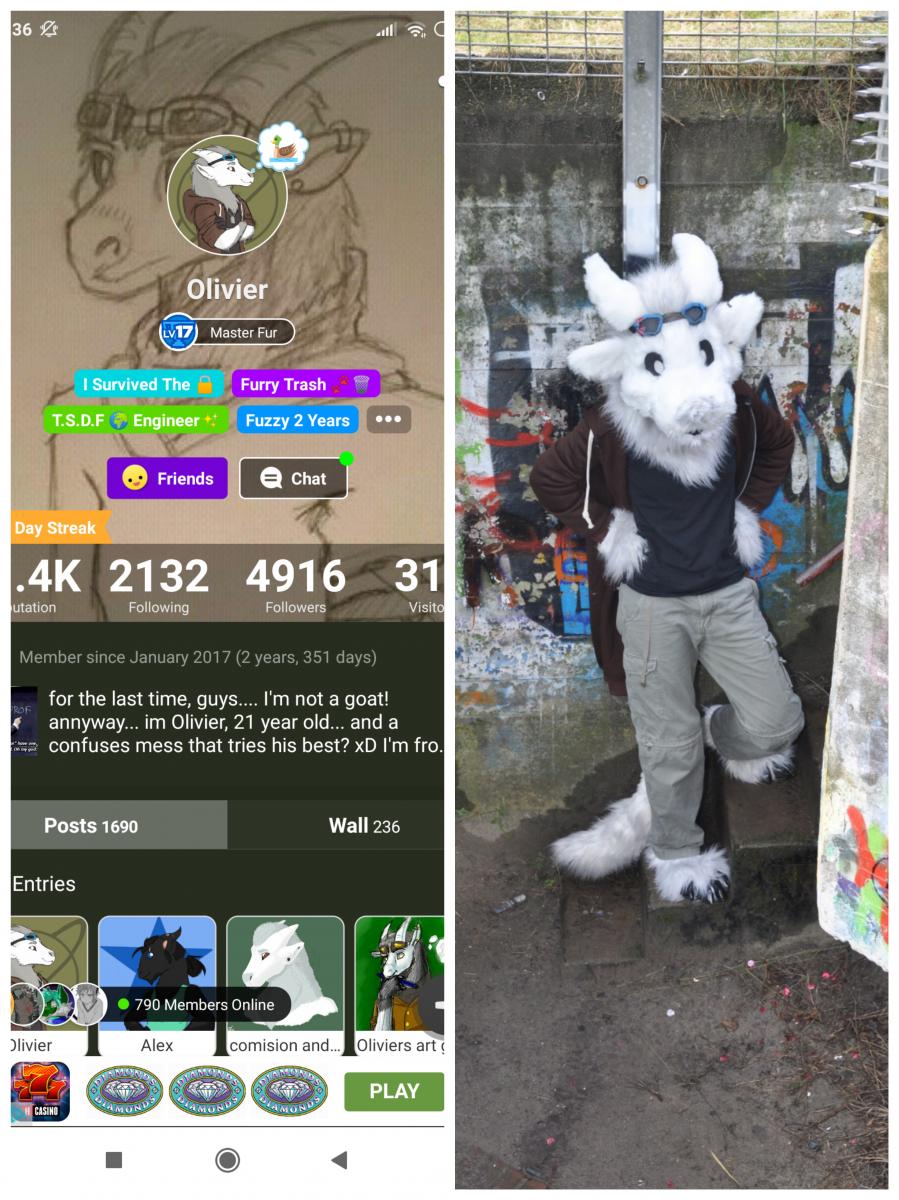

figure 1) Display of a furry identity online and offline

These fursonas do not necessarily have to be based on real animals, but can also be a mix of different species, be an original species (such as Dutch Angel Dragons) or be a mythological/fantasy species. The character in Figure 1 is an original species created by the owner of the fursona. The degree of realism of the colours and markings can also vary. It is most common for furies to have one fursona, but some have multiple that they switch between. Over time, one can choose to create a new one to better represent themselves. Since fursonas often have a lot of emotional value (and sometimes financial value) to their owner, it is highly disrespectful to use someone else’s fursona for yourself.

Another major norm of the community is acceptance, and a big reason for joining the fandom is having a feeling of belonging. A large percentage of the fandom is part of the LGBT+ community, and this percentage is much larger compared to the percentage of the general population. The fandom gives these members a safe place to express themselves and to meet people like them (Plante et al., 2016).

The amount of norms you need to take into account as a member also depends on the sub-groups and, generally, the context you find yourself in. Take, for example, the sub-group of fursuiters. Fursuiters are furries who own and sometimes walk around in a costume of their fursona. The picture on the left in Figure 1 is an example of a fursuit. Fursuiters need to take into account the norms for suiting, which are similar to the norms for cosplay. This includes the unspoken rule of not breaking character. (Or, as they say in the furry fandom: “Don’t break the magic.”)

Furry language

The furry fandom has its own supervernacular specific to the fandom. A supervernacular is a collection of little bits of linguistic and other visual signs that, whenever used, create and activate a shared vocabulary that can engage participants in elaborate forms of interaction (Blommaert, 2012). You have already learnt a couple of terms in the paragraphs above, such as "fursuiter", "furry" and "fursona".

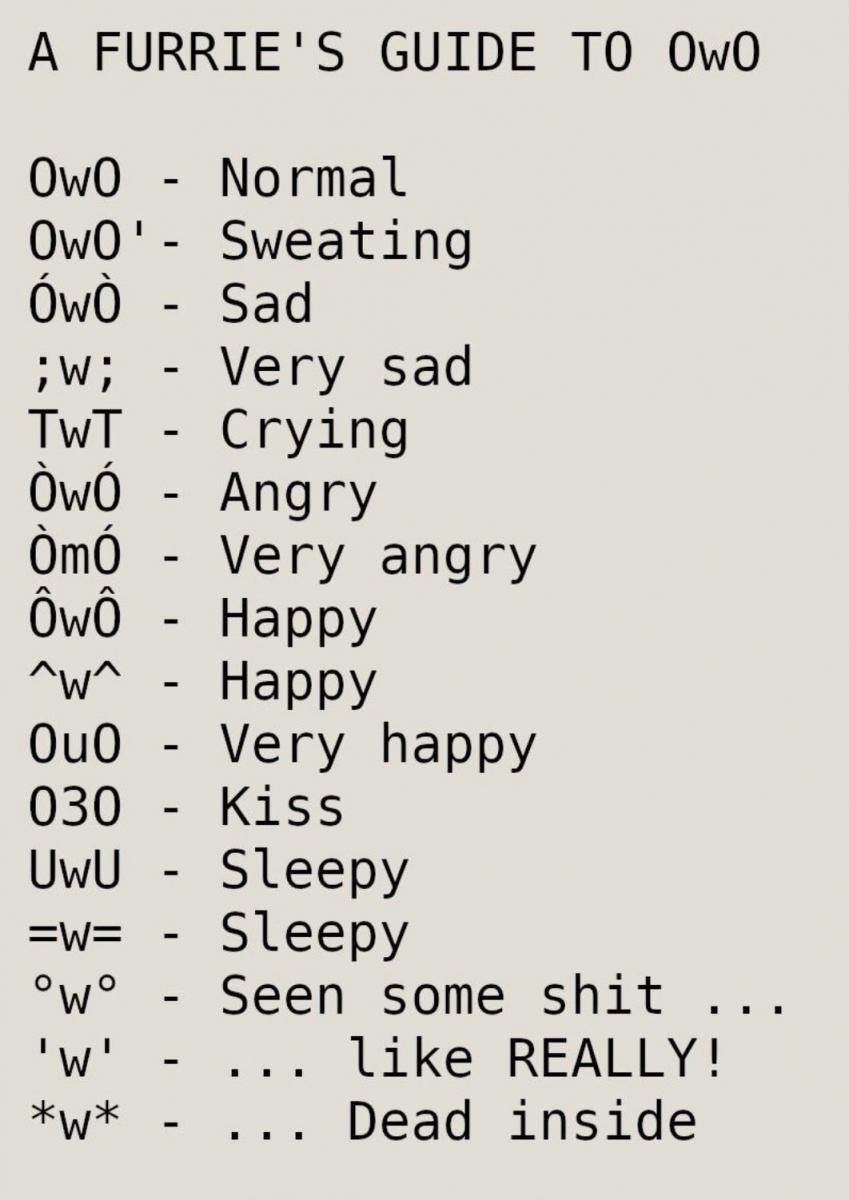

figure 2) 'Furry emojis' are part of the furry super vernacular

Within the furry fandom, it is also normal to use the emojis shown in Figure 2 instead of regular emojis. OwO is often used in combination with “what’s this?” and is meant to show surprise, but can also be used in other contexts. The reason for using these emojis instead of regular emojis is that the character "w" makes the typed emoji look more like a cat face, which is in line with a furry’s adoration for animals.

Finally, it is also worth noting that fursuiters constitute an emblem of the furry fandom, which influences the language used to describe the community. Although only a small percentage of the fandom owns a fursuit, non-furries often use the terms "furry" and "fursuiter" interchangeably. On the topic of emblems, “fursuit parts” such as ears and tails can also be considered emblems and can be worn by furries on a day-to-day basis.

Commodification and infrastructure

As a large social group, the furry fandom has its own offline and online infrastructure that allows for commodification. Their online infrastructure does not only span across established global platforms used by non-furries, but also includes furry-specific platforms. Furaffinity, for example, is a social networking site dedicated to the furry community. The messaging app Telegram is also hugely popular and the fandom also has a large and active community on Amino.

Offline, there is also plenty of infrastructure that is often promoted online. Examples include furmeets, which are events organized by furries for furries, and cons (conventions), which are larger events often not organized by furries. These cons can be for furries only, such as Midwest Furfest, or for a multitude of niched cultures such as San Diego Comic Con .

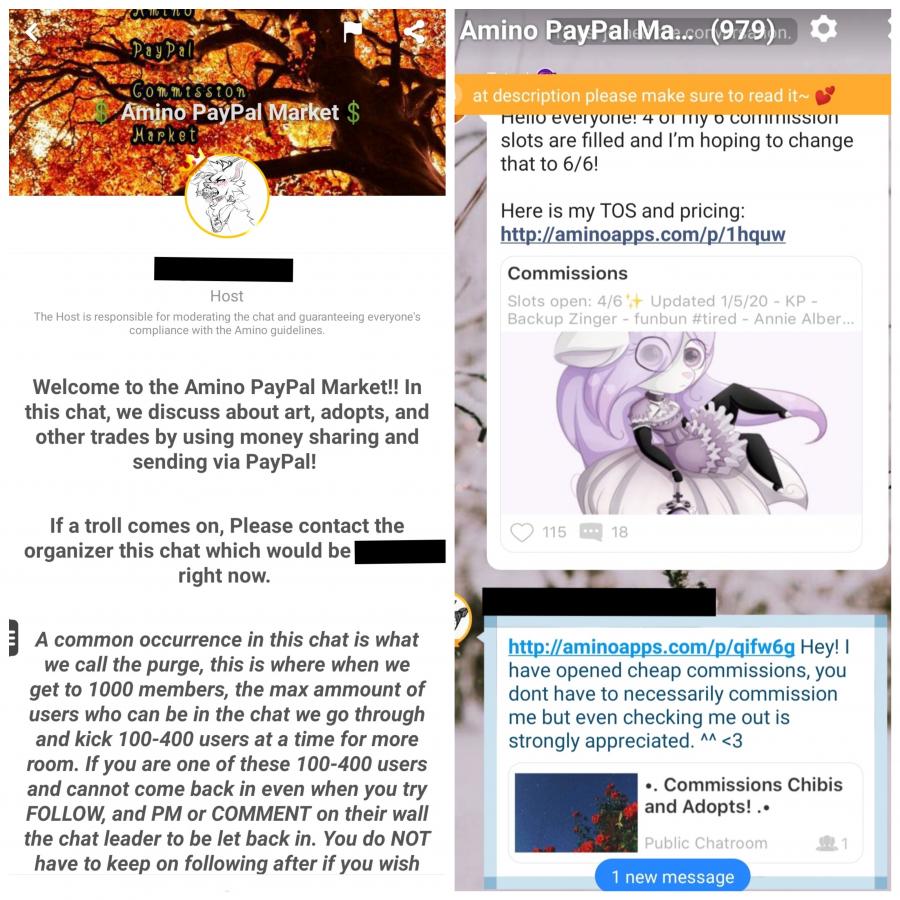

Figure 3) A chat on furry amino dedicated to advertisement

An important role of these elements of infrastructure is to facilitate the monetization of the furry community. While not a necessarily a norm, a lot of furries enjoy buying artwork (both physical items and digital artwork) of their fursonas and it is a dream for a lot of furries to one day be able to buy a fursuit (Plante et al., 2016). Both the online and offline infrastructure of the fandom provide ways for artists to make a living off creating artwork and costumes for furries. One case of relevant infrastructure is the Dealer’s Den. It is an online market for artists to sell their goods and it is named after the place where merchandise is sold at cons. On other platforms, groups or chats can often be found that are specifically created for advertising one's goods. Figure 3 is an example of such a chat.

Because the fandom is based on a plethora of properties and user-generated content (Plante et al.,2016), it is futile for large media companies to tailor their merchandise to the furry community. That being said, furries are likely to support properties with anthropomorphic animals.

Approach

For my research, a digital ethnography approach was adopted. Digital ethnography is a specific approach for doing research "on online practices and communications, and on offline practices shaped by digitalisation" (Varis, 2014). This is done by collecting online data (often in the form of screenshots) and observing a certain group through the lens of the study's subject.

To protect the privacy of the informants, permission was asked for the use of screenshots. All usernames have been blacked out as well for the same reason (except the one appearing in Figure 1, which was kept visible with permission).

Furry Amino, a group on the social media platform Amino, is the focus of my research. This specific group was chosen for a variety of reasons. First of all, the userbase is relatively big, allowing for ample data collection. Secondly, the group has a wide variety of functions, such as blogs, chats and more, making the content produced therein diverse. Lastly, I already had experience using the platform and had a few contacts willing to help me, allowing for easier data collection. This is my main source of data, but I will also be mentioning other platforms such as Discord as well.

Constructed deviance

Furries are often seen by other groups as deviant. They are seen as odd and disgusting due to large misconceptions or a reliance on unnuanced facts. Such ideas include that furries endorse bestiality, that the fandom is based around sexual activities and that furries are mainly unhealthy men in their thirties. I could spend this blog debunking all of these beliefs, but instead, I will look at how non-furs come to believe these falsehoods. If you are interested in more information on furries debunking these misbeliefs, I highly recommend you give fur science! a read.

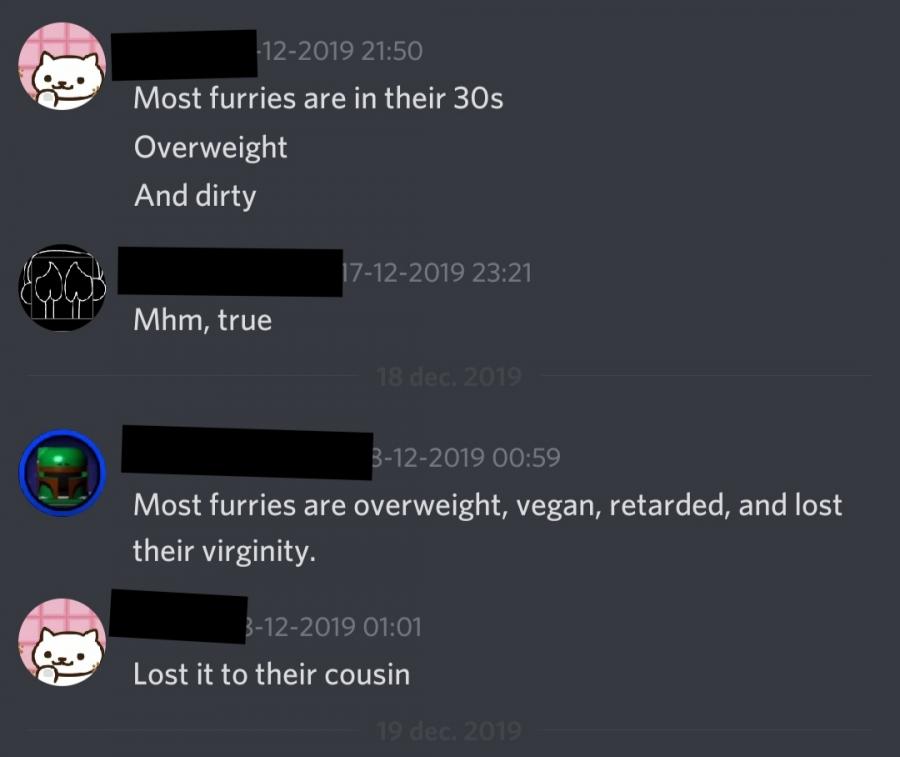

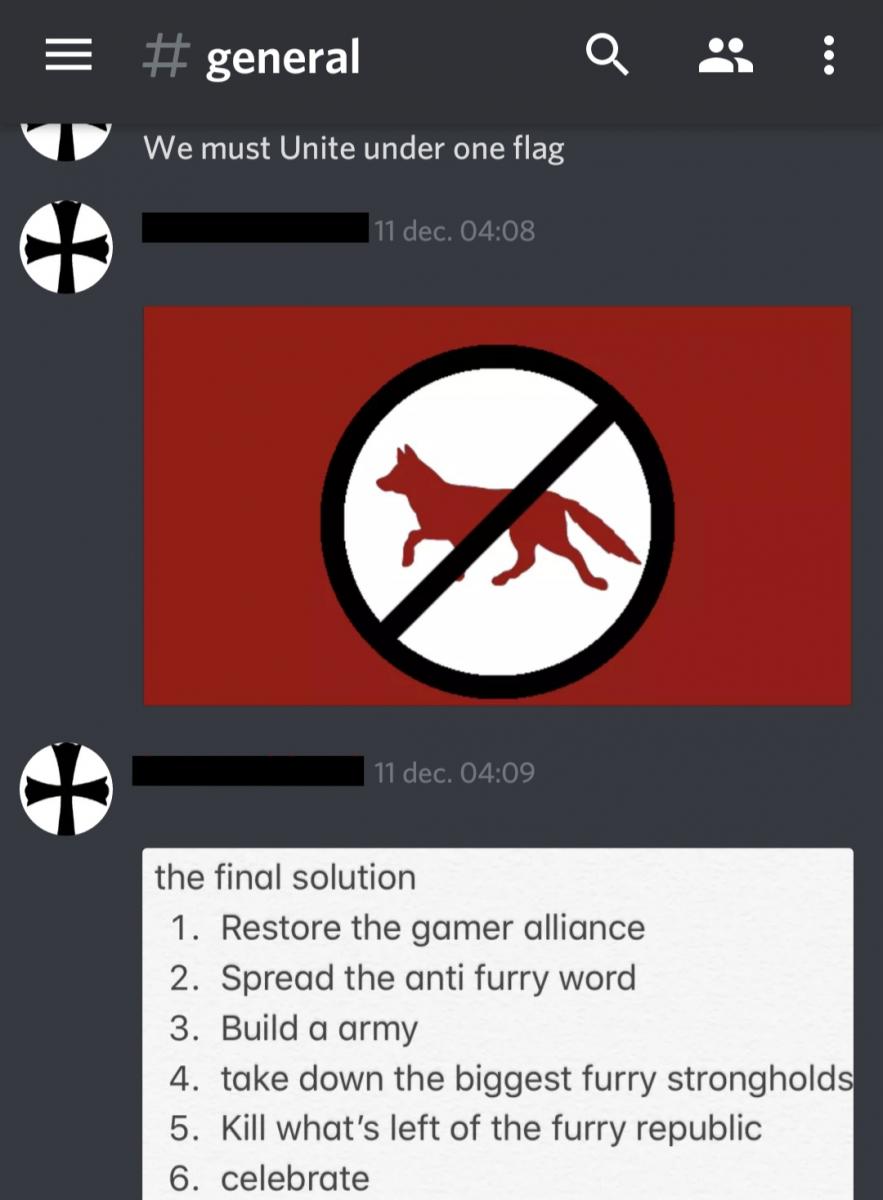

figure 4) False information about furries on a discord server

The explanation often given for these misconceptions is furries' misrepresentation in traditional media. An example of this media misrepresentation of furries is an older episode of CSI entitled “Fur and Loathing” in which the entire community is painted as a sexual deviants.

However, with the more recent positive attention the fandom has gotten in the media (such as this Vox video), this explanation does not entirely hold up. The explanation can instead be found online, where misconceptions easily spread amongst people uninterested in checking the facts. These misconceptions spill over into the offline world, where they can have harmful implications for those who are part of the furry fandom.

figure 5) Offline misinformation about furries having a negative impact

Hating on furries is not always serious, however, and it has become somewhat of a meme online. The “furry wars” are the most infamous of these ongoing memes and feature the gamer community “going to war” against the furry community. While this has gone on for a long time, its most recent iteration has been taking place on TikTok. Not just the gamer community, but also the weeaboo (anime fans) community and meme community are participating in the furry wars.

Figure 6) An innocent meme or a hate fueled campaign against the furry community? Anti-furry servers are abundant on Discord.

However, sometimes it is hard to see where the fun and memes end and where the genuine hate against the community starts. The Discord server shown in Figure 6 is one of various anti-furry servers that promote the furry wars. It is one of the places where gamers who want to contribute to the war gather and plan so-called “raids”, in which a group of members gather to troll the community on a certain platform. Can these raids still be justified as good fun and part of the meme? Or are they malicious trolling trying to hurt furries and their fandom?

Furthermore, this meme also normalizes hating on this community and helps spread misinformation. What the sender may believe to clearly be an unrealistic characterisation and stereotyping of a furry, may be perceived as a call out of a genuinely harmful group by another user.

Deviance within the fandom

An interesting paradox is visible within the fandom. Despite its emphasis on acceptance as the norm, deviance is still constructed within the group. This part of the paper will cover what I found to be the most important groups that are seen as deviant while also attempting to explain why they are constructed as such.

Women and subgroups

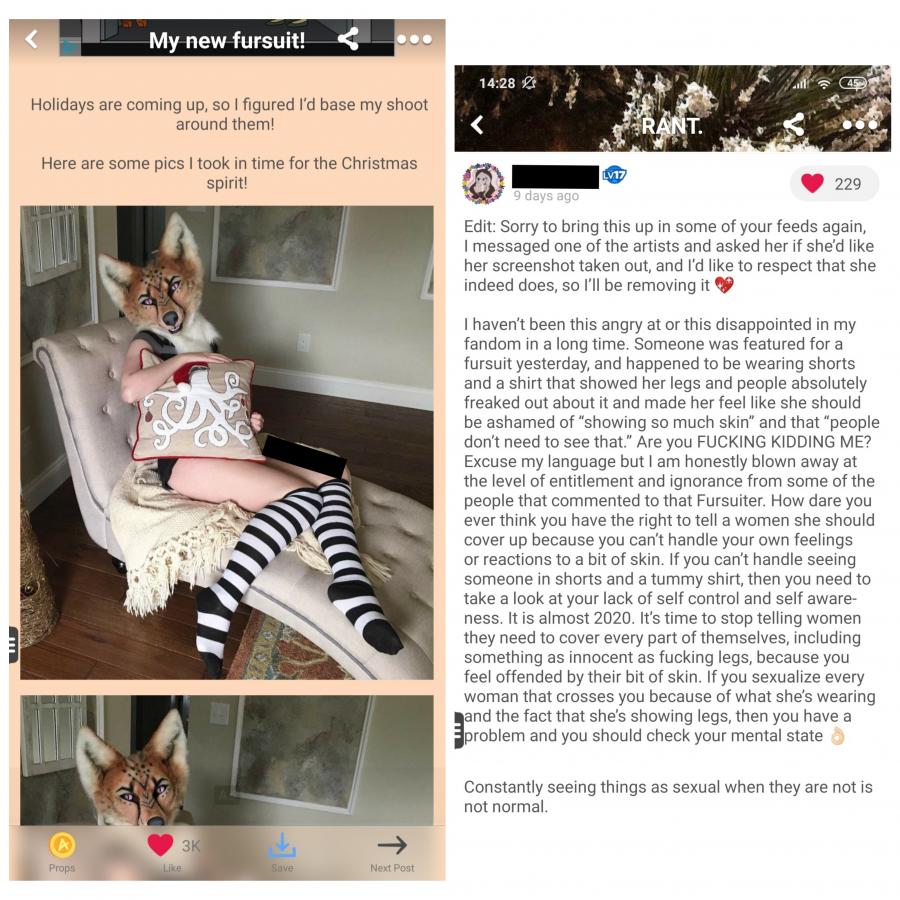

Women are a minority within the furry community, which can lead to them feeling intimidated. They often also face harassment, such as body shaming and unwarranted sexually tainted messages (Plante et al., 2016).

Figure 7) A featured fursuit post that received a lot of body-shaming comments and a post reacting to these negative comments.

Female furries are trying to bridge the gender gap by establishing themselves firmly as artists within the community. In fact, they outnumber male artists selling at furry conventions. They are also more likely to join the fandom through being an artist than men are (Plante et al.,2016). This shows interesting parallels with the gaming community, where aspiring female game developers try to get a foot in the door by getting into the cosplay scene:

“For some of the female students enrolled in games degrees, cosplay can be a way not only to connect with others who enjoy consuming ‘Japan’ but also provide avenues for gendered performativity and empowerment. As the young female student noted above, the fact that most cosplayers are female afforded her with a space to build strong female relationships in an industry still attempting to address its gender inequalities” (Pink et al. 2016).

Further, the furry community is a polycentric social group, which means that its members gravitate to various centres of normativity. This is how various subgroups are formed. Some subgroups are looked down upon, especially if they go against the norms of the furry community.

Subgroups that go against the norms of the furry fandom are looked down upon.

An example would be that of alt-right furry groups. There already is larger social disdain for extreme-right groups that transcends the furry fandom. Couple this with the fact that the majority of furries is left-leaning (Plante et al.,2016) and the importance of acceptance within the community, and you’ll start to understand why this group is looked down upon.

Fetish groups such as baby-furs, mursuiters (people who have sex in their fursuit) and vore endorses are outcast by a large portion of the fandom. This is most likely due to the fact that these groups corroborate the already negative sexual reputation of the furry fandom.

Enough is enough

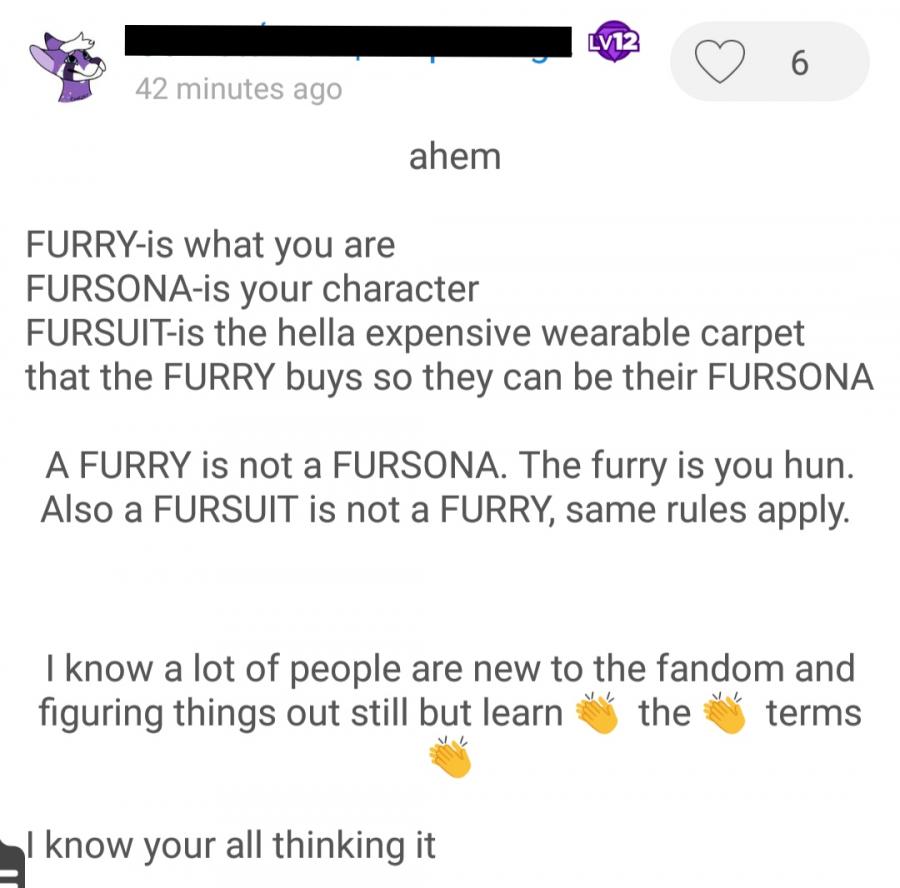

“One needs to be ‘enough’ of a rapper, not ‘too much’; the same goes for an art lover, an intellectual, a football fan, an online game player and so forth” (Blommaert & Varis, 2015).

This is also the case in the furry community. If you display too many furry accents, you can be seen as cringy. Take, for example, the song above, which is a parody based on over-exaggeration of normal furry speech and behaviour. It is seen as cringy because it is too sexual (which is a reputation the fandom is trying to do away with) and too many "furry" words/phrases are used. This behaviour is often associated with new members of the fandom and younger furries, who have yet to grasp the subtleties of the furry identity and the language associated with it.

Figure 8) A furry schooling new members on furry terms

A slippery slope

As stated above, trying to balance the fine line between having enough furry identity markers and too many can be a slippery slope. If you display too many identity markers or display unwanted behaviour, you may risk being seen as a deviant.

The furry community itself is also seen as a deviant group by a lot of non-furries. It is often unclear when the line between innocently making fun of the group and maliciously trolling it is crossed, which can lead to the spread of misinformation. Further research into how furries' deviance is constructed could lead to interesting new insights.

References

Becker, H. (1997). Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. Free Press.

Blommaert, J. (2012). Supervernaculars and their dialects. Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1. 10.1075/dujal.1.1.03blo.

Blommaert, J. & Varis, P. (2015). Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities. Tilburg papers in Culture Studies.

Pink, S., Horst, H., Postill, J., Hjorth, L., Lewis, T., & Tacchi, J. (2015). Digital Ethnography: Principles and Practice. SAGE publications.

Plante, C., Reysen, S., Roberts, S., Gerbasi, K. (2016). Furscience: A Summary of five Years of Research of the International Anthropomorphic Research Project. Waterloo, Ontario, Canada.

Varis, P. (2014) Digital ethnography. Tilburg papers in Culture Studies.