EU and Digital Literacy Skills in Europe's Digital Decade

With the emergence of digitalisation, society has become a nexus between online and offline. It has started to depend heavily on digital technology and thus needs people who can navigate their way through the new digital society. Being able to work with such digital technology, however, requires a significant digital skillset and thus depends on digital literacy. But such a skillset, or being digitally literate, is not a given.

On the contrary: within a society that so strongly depends on the digital, a surprisingly large group still lacks the right digital skillset and is thus digitally illiterate. The European Union (EU) realises that the problem is of greater significance than it seems. Therefore, they structured The Digital Decade Policy programme, a several-year plan to get 80% of their population digitally literate by 2030. We will use data to analyse the current progress, and judging from said data, we plan on analysing differences between countries as a cause for the goal's reachability. Finally, we intend to investigate whether the 80% goal in 2030 is feasible or should be subject to refinement.

The Importance of Digital Literacy

We ought to introduce some theories that further explain the meaning of digital literacy and why it is essential for the EU and its citizens before concluding if the EU can reach its 80% goal for digital literacy. Before the digital age, society only knew literacy in itself. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (2023) defines literacy as being able to “identify, understand, interpret, create, communicate and compute, using printed and written materials associated with varying contexts”. On top of that, UNESCO states that literacy is essentially a human right.

According to Belshaw (2016), literacy is, in essence, a spectrum. There are several degrees to literacy, with someone being more or less literate rather than entirely literate or illiterate. Literacy should be approached from a digital perspective because humankind lives in a diachronically online world. That is where digital literacy becomes necessary.

One thing we could easily conclude about the term digital literacy is that, although there are multiple similar definitions out there, there is not one prominent definition everyone applies when referring to digital literacy. In his book The Essential Elements of Digital Literacies, Belshaw mentions that the definition of digital literacy depends entirely on the situation someone finds themselves in. However, to provide clarity, we will stick to the meaning of digital literacy provided by UNESCO, as we believe it succeeds in combining multiple other definitions.

In What You Need to Know about Literacy, UNESCO (2023) defines digital literacy as “the ability to access, manage, understand, integrate, communicate, evaluate and create information safely and appropriately through digital technologies for employment, decent jobs, and entrepreneurship. It includes skills such as computer literacy, ICT literacy, information literacy, and media literacy which aim to empower people, and in particular youth, to adopt a critical mindset when engaging with information and digital technologies, and to build their resilience in the face of disinformation, hate speech and violent extremism.”

As part of their digital literacy target of 80%, the EU specified that they want to have a digitally skilled population and, on top of that, professionals who are skilled in the digital field. On the webpage about Shaping Europe's Digital Future (2023), the page dedicated to digital skills highlights how the EU defines digital literacy and if their definition matches the one mentioned above.

A few of the digital skills, as mentioned above, are knowing how to look something up online (the ability to understand, access, and evaluate), but also being familiar with how to manage money using digital technologies and the ability to navigate through social media to communicate and seeing its value as a communication method. Digital skills are not only used for personal matters. The EU also strongly emphasises applying digital skills in a professional environment. Most employment fields require a particular digital skillset for an optimal work environment and experience. Therefore, digital literacy has proven to be a vital feature of the work environment in our digital society. Hence, we can consider the digital skills defined by the EU as part of digital literacy.

Digital rights and principles for the Digital Decade

The EU digital literacy targets for 2030 highlight the notions of solidarity, inclusion, and participation and put people at its centre. A certain degree of inclusion is required to achieve these features of the 2030 goal, and democracy is arguably the better method to get to said achievement. Through democracy, the EU wants to unite people by granting access to digital technologies. The reason for this approach is that everyone should be able to actively participate in and support democracy and engage with political processes, all while maintaining control over their data. Engaging with democracy through digital technology requires knowledge of digital technologies and the ability to navigate through them. To understand democracy and engage in its processes, mastering digital skills is of significant importance.

Without information and knowledge, there is little to no ground for EU citizens to engage, form, and share their voices, which Buchholz et al. (2020) also highlight in their research. Hence, a lack of knowledge will further enhance inequality within the EU and among its citizens. Said knowledge can solely be authorised, issued, and authored by an institution. Hence, the European Commission is in charge of the knowledge and its authorisation to increase the success rate of the digital literacy goal and avoid inequality in this field.

The ability to carry out literary functions is affected when differences occur regarding access to literacy and literary resources, whether digital or not. In the case of digital literacy, however, said functions are linked intrinsically to digital technologies. Every country works with different methods, and, likely, one country is a few steps ahead in development and wealth than another. Hence, every country has different access to digital technologies and thus their requirement for digital skills. For the data analysis part of the paper, we will dive further into the difference between countries and their wealth, their use of digital technologies, and how their development happened in recent years. Furthermore, the analysis will account for our conclusion regarding the feasibility of the EU digital literacy goal.

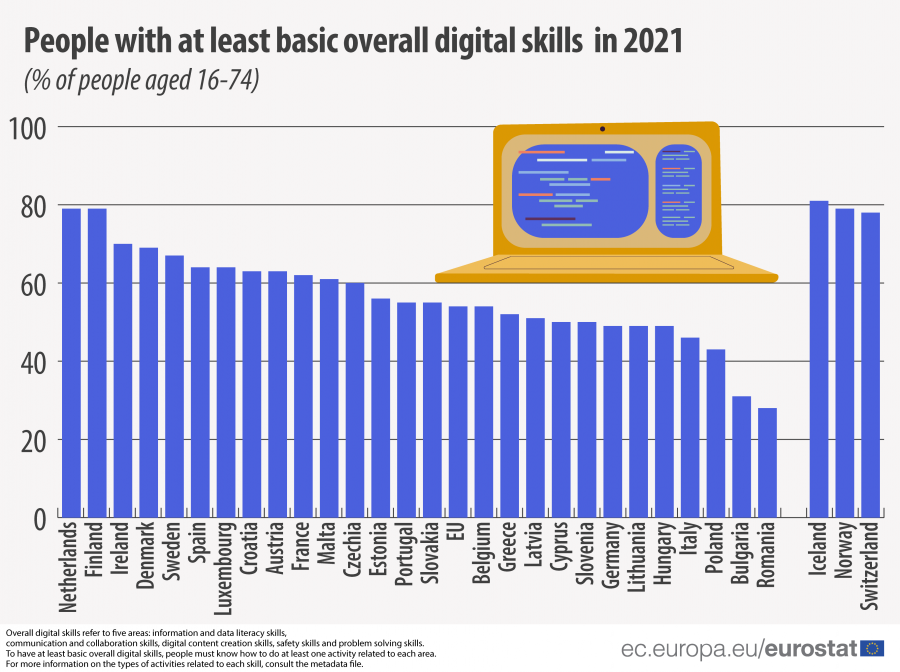

The European Citizens as Digitally Literate

In 2022, Eurostat published an article highlighting the basic digital skills of people (ages ranging from 16 to 74) in 2021, differentiating between different European countries (not to confuse with EU countries, because Switzerland is there as well). The graph (Figure 1) points to significant differences in the quality of digital skillsets between the European countries involved in the research. These differences are especially noteworthy because, as mentioned above, almost all job fields require digital skills nowadays. Hence, there need to be additional reasons that account for the big difference.

Figure 1: Graph from Eurostat regarding the basic overall digital skills of European citizens in 2021. © Eurostat, 2022

Looking at the overall results, Eurostat concludes that only 54% of this age group qualifies for the basic overall digital skills, meaning that approximately half of the European population is behind and, therefore, unable to engage with digital technology. These overall digital skills Eurostat refers to include five areas: " information and data literacy skills, communication and collaboration skills, digital content creation skills, safety skills, and problem-solving skills." (Eurostat, 2022). To obtain overall digital skills, one must know how to do at least one activity related to each area. In their metadata file, Eurostat elaborates on these five areas and the skills that match them.

When taking a closer look, the inequality between countries is evident, but even a definite pattern is noticeable. Looking at the numbers from the Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Finland, and, in this case, Iceland), the Netherlands, and Switzerland, these countries score incredibly high on overall digital skills. Although Denmark and Sweden score relatively low, they still count as some of the highest among European countries (the same goes for Ireland).

When comparing their scores to those of Eastern European countries (think of Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland, and Slovenia, for example), there is a prominent gap between these two groups. Logically, some Eastern European countries score higher than others (the Czech Republic and Croatia, for example). Yet, there is a clear difference when generalising Eastern Europe and Western Europe. As mentioned in the explanation following the graph, Eurostat highlights that the highest scores were found in the Netherlands and Finland (79%), followed by Ireland (70%). The lowest scores were recorded in Romania (28%), Bulgaria (31%) and Poland (43%).

In the TEDxTalks with David Times on why digital skills matter (2017), it can be seen that this is nothing new and that in 2017 an Eastern European country (Romania) was already behind on digital skills. Only 26% of Romanian people possessed basic skills at that time, which in itself is already concerning. What is more concerning is that in 2021, as was seen before, there is still a big part in especially Eastern Europe that cannot keep up with developing the digital skills for their citizens.

As the Eurostat article mentions, "Digital skills indicators are some of the key performance indicators" (Eurostat, 2022) for the EU's digital literacy goals and transformation. Their 80% aim was far from being reached in 2021.

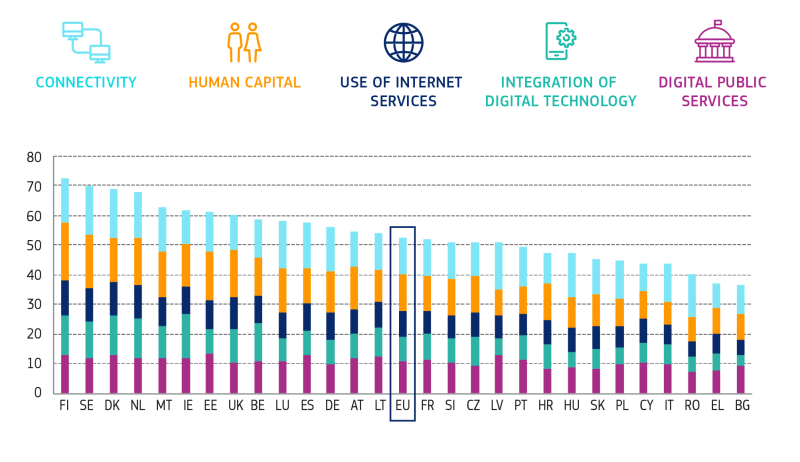

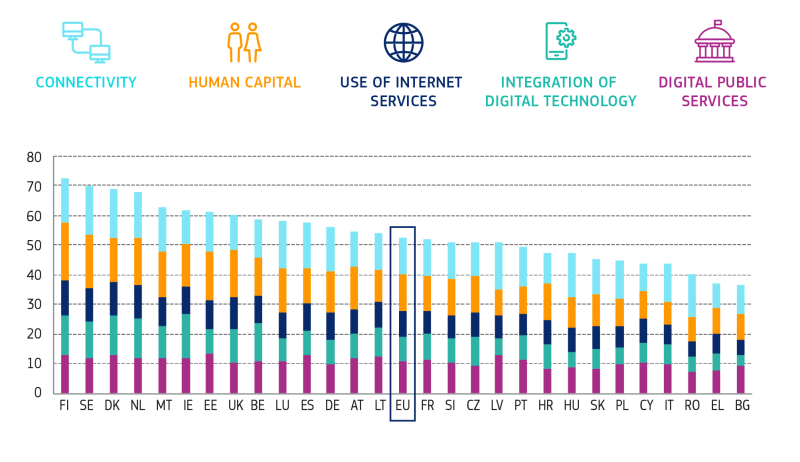

These prominent digital skillset differences between Western and Eastern European countries could be the product of inequality. The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI) of 2022 (n.d.) elaborates on these inequality matters between several European countries. The European Commission gathered this data through the DESI to monitor the digital progress of its member states. The DESI publishes one report every year. Every year, the DESI includes country profiles for each member state, including areas that require priority treatment, and "thematic chapters offering a European-level analysis across key digital areas." (The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI), n.d.).

The DESI 2022 is based mainly on data from 2021 and tracks the digital progress of EU member states. Its main finding was that, despite the COVID-19 pandemic and the urge from member states to advance digitalisation efforts, they still face difficulties closing the gaps in digital skills.

The DESI clears up some of the inequality among European countries. The webpage includes the graph, and also the yearly report and the individual member state profiles for each country. The graph (Figure 2) provides a clear overview of the indicators accounting for digital skills per country. The graph is thereby similar to the one mentioned above in Figure 1.

© European Commission

© European CommissionFigure 2: DESI graph, including five indicators that play a role in inequality

Figure 2: DESI graph, including five indicators that play a role in inequality

A similar finding among Figures 1 and 2 is that Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands score high in both graphs, whereas the Eastern European countries (Bulgaria and Romania) score relatively low. Generally speaking, Eastern European countries have a smaller percentage of success regarding the integration of digital technology and skills compared to Western countries.

The DESI graph includes five indicators: integration of digital technology, use of internet services, human capital, digital public services, and connectivity. Especially a matter like connectivity highlights inequality differences between countries because gathering digital skills depends on the ability to access the Internet. Citizens in countries that score low in these graphs are likely to get even further behind on digital skills and run the risk of being excluded from matters requiring digital skills. The lack of engagement abilities in democratic cases will decrease because, to participate, one ought to understand digital technology. Obtaining human capital will likely be impossible (skills and knowledge) without involvement in the digital world.

A Challenging Goal for Europe

The conclusion is indisputable, judging from the data analysed for this paper. From what we can tell from the most recent data, the EU currently finds itself at a 54% mark in its journey to a population that is at least 80% digitally literate. It is not rocket science to conclude that they still have a long way to go to reach this 80% goal. They are currently 26% short and need a way to find these lost percentages somewhere, as the clock is ticking, and every second is valuable.

Generally, Western countries are well on their way to reaching the 80% goal. Most countries in the Western part of Europe are at most 20% away from the 80% goal, so there is a relatively small gap for them to close in the leftover seven years. For Eastern Europe, however, their journey will require more effort. The average Eastern European country is close to 50% and often even below this percentage. Add their lesser wealth to the mix, and it will make for a difficult task to get to 80%.

So for some countries, the goal is feasible, whereas, for others, the 80% will undoubtedly be challenging to reach. The EU goal of 80% is thus feasible but only barely. The EU needs to take appropriate and significant measures if they are actively serious about reaching their goal.

What can Europe do now?

Strict measures are needed if the EU wants to reach the 80% goal by 2030. The methods they apply have proven to result in progress in various cases. Some countries, however, still stay behind and thus need to alter their techniques slightly to stand a chance of reaching the 80% goal.

As mentioned above, literacy functions as a spectrum. One is not either literate or illiterate: instead, there are several degrees to being literate. Arguably, this approach to literacy could further add to reaching the 80% goal. The basic overall digital skills Eurostat mentioned would be an applicable example to illustrate this proposal. Eurostat used five areas to account for digital skills: if someone can do at least one activity from all five fields, they are considered digitally skilled. Developing this idea further, the more activities one can do corresponds with a greater digital skillset.

The EU could introduce degrees of literacy and structure these degrees similarly to the language levels such as A1, A2, B1, and so on. They could then set a minimum requirement for all citizens to get to one of the levels of digital skills, say B1, for example. The EU could create teaching programs that can function as guidance for countries to get their population to become digitally literate to strengthen this idea further.

These programs could include lessons given by professionals, where they teach digital skills depending on the class level, with B1 classes teaching B1 activities, for example. Such lessons are nothing new: volunteers created such lessons to help the elderly improve their digital skills, and the videos from these lessons often go viral on social media. However, the EU could take this idea to national levels for this proposal. These classes could extend over a certain period and then be followed by tests to account for the digitally literate level and provide proof in the form of a certificate. Such a certificate would also help keep track of the progress and can help get a clearer view of the fields that require extra attention.

Bibliography

Belshaw, D. (2016). The Essential Elements of Digital Literacies. [Ebook]

Buchholz, B. A., DeHart, J., & Moorman, G. (2020). Digital citizenship during a global pandemic:

Digital skills. (2023, April 18). Shaping Europe’s Digital Future.

Europe’s Digital Decade: Digital Targets for 2030. (n.d.). European Commission.

Eurostat. (2022). How many citizens had basic digital skills in 2021? Eurostat.

Individuals’ level of digital skills (from 2021 onwards) (isoc_sk_dskl_i21). (n.d.).

Literacy. (2023, February 28). UNESCO UIS.

Moving beyond digital literacy. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 64(1), 11-17.

TEDx Talks. (2017, April 4). Why Digital Skills Matter | David Timis | TEDxTârguMureș [Video]. YouTube.

The Digital Economy and Society Index (DESI). (n.d.). Shaping Europe’s Digital Future.

What you need to know about literacy. (2023). UNESCO.