Fashion as tyranny: beauty standards and social pressure

Included or excluded?

This article investigates how fashion puts social pressure on women. The focus will be on fashion models coming from different cultures: Lee Geum Hee from South Korea, Adriana Lima from Brazil and Bette Franke from the Netherlands

Two different mannequins

While traveling through Costa Rica for two months in 2015, I came across the mannequin shown in Figure 1 (below) on the left. It goes without saying that this Costa Rican mannequin used for displaying clothes is clearly different from the mannequins in the Netherlands, shown on the right in Figure 1. The two mannequins have obvious different body shapes, i.e., curvy breasts and lower bottoms versus a much slimmer shape. Why does body shape matter here? Is it an aspect of fashion? And why is this different when comparing different parts of the world? Such questions are at the basis of this article in which I explore the issue of how fashion exerts social pressure on women.

Figure 1: Mannequins

The term "fashion" refers to the latest or most admired style (Collins, n.d.). In the field of dressing and clothing, this means how people dress based on a current idea of a particular society; what is a nice way to dress. The terms dressing and clothing will be used interchangeably here and will be seen as a gathering of body modifications and additions (Roach-Higgins & Eicher, 1992). Clothes are an important aspect of our daily life. According to Dunlap (1928) there are different theories about the origins and functions of clothing:

- The modesty theory: Clothing has as an original aim to conceal genital organs.

- The immodesty theory: Lust is the aim for clothing; they are used to attract attention to the sexual organs and sexual functions.

- The adornment theory: Clothes are to seek attention; they are seen as a decoration.

- The utility or protection theory: Clothes are to protect the body from unpleasant features.

Also, a possible reason for dressing could be that through clothing people can create an identity (Entwistle, 2015). Of course, people can have additional reasons for clothing.

Meet the models

In this section, three women will be presented. They are all famous fashion models, and I will go into some of their specific characteristics as related to the different cultures they come from.

Lee Geum Hee

Lee Geum Hee is a 23-year-old Korean model. She is number two on the Ulzzang list (Listal, 2013). The word Ulzzang is used in Korea and stands for ‘best + face’. On this list are basically people with above average looks that sometimes become Internet celebrities (Urban Dictionary, 2008). So by many Asian women the appearance of Lee Geum Hee is seen as an ideal (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Collage of modeling pictures of Lee Geum Hee

In all of her pictures, Lee Geum Hee looks cute. She provides this appearance by wearing specific clothes, using specific accessories (for example the lollipop) and showing a specific hairstyle (the color of and accessories in her hair). The pictures of Lee Geum Hee show that her style is related to the Japanese Kawaii (cute) style. The Kawaii style is a Japanese subculture (Ngai, 2005) and essentially means childlike. It is clothing that stands for sweet, adorable and innocent social and physical appearance (Kinsella, 1995). The Kawaii style began in Japan around the mid-1970s and gradually received more attention of magazines. Around the 1980s, it even became a trend for women to wear underwear that looks like children’s underwear (Kinsella, 1995). This underwear is still purchasable through different web shops (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Picture from an advertisement for Kawaii style underwear

Where other fashion trends come and go, the Kawaii trend became a subculture and there are still many models, as for example Lee Geum Hee, that dress according to this style. Noticeable is that Lee and many other models that appear in the Kawaii style are not Japanese, which indicates that the original Japanese style also is popular in other Asian countries.

Adriana Lima

In Brazil, it is a fashion trend to look sexy. In order to explain this trend we take a look at the Brazilian model Adriana Lima (see Figure 4). She is working for the brand Victoria’s Secret that, among other things, sells lingerie. The quote of Victoria’s Secret is “The sexiest bras, lingerie and women’s fashion” (Victoria Secret, n.d.).

Figure 4: Collage of modeling pictures of Adriana Lima

Different sources describe Latinas in a rather stereotypical way as women with sexy curves: “Nothing is more provocative than a curvy, well-proportioned figure like those exhibited by so many Latina and Hispanic women” (Bal Harbour Plastic Surgery, 2011), and “the curvy Latina stereotype is that they have big breasts, toned arms, small waists, thick hips, and thighs that touch” (Reichard, 2013), or “Latina women are curvy, sexy and sultry” (Nittle, 2016).

Furthermore, a search command on Google for ‘Brazilian women’ shows mostly pictures of women in bikinis (Figure 5). This might make people think that being Brazilian and being sexy is interrelated. It is imaginable that the equation of being a Brazilian woman and being sexy can put quite some pressure on Brazilian women to try to look as sexy as the models featured in fashion magazines and blogs.

Figure 5: Google Search command ‘Brazilian women’

Bette Franke

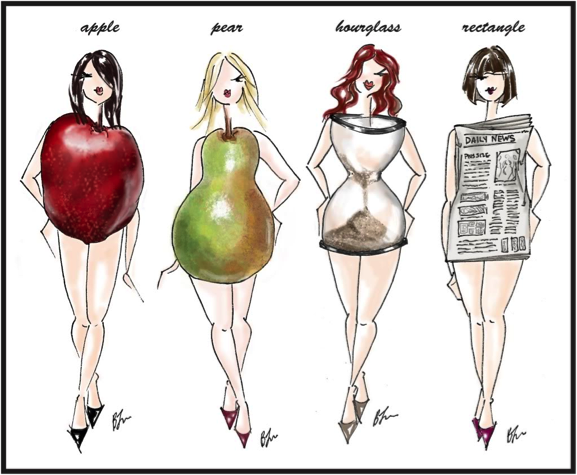

Let’s now have a look at Dutch example. Contrary to search commands on ‘Korean women’ or ‘Brazilian women', a search command on ‘Dutch women’ does not show a specific fashion trend or stereotype as ‘cute’ or ‘sexy’. However, a Dutch woman is described as a woman that is beautiful in her simplicity (Kramer, 2011). The reason that there is no stereotypical beauty description can be caused by the fact that their appearance differs from brown to blond to red hair, from blue to green to brown eyes, but also that the bodies of Dutch women differ from apple, pear, rectangle to hourglass shape as defined by Loenen (2011) (see Figure 6). Of course, also the Korean or Brazilian women differ in their appearances, but this seems to be experienced as less diverse than in the Netherlands.

Figure 6: Overview of different body shapes

There is no stereotype of the appearance and body type of a Dutch woman; however, through different fashion marketing and consumer products, such as corsets, push-up bras, diets and plastic surgeries, there are two ‘ideal’ body types used for fashion. Namely, the Latina body stereotype—which is comparable to the hourglass shape—and the body of a runway model, the rectangle shape.

An example of a runway model is the Dutchwoman, Bette Franke (Figure 7). She works for different ‘expensive’ brands, such as Calvin Klein and Prada. She is 1.78 meters tall and is obviously less curvy than Adriana Lima. Bette Franke looks like many other women that are modeling for clothes in online shops like www.gucci.com or www.chanel.com, but also in less expensive stores such as H&M or Zara.

Figure 7: Collage of modeling pictures of Bette Franke

Women with shapes like Bette’s are in the fashion branch considered the ideal woman. But not everyone agrees with this. This is visible on different reactions and feedback given on Bette Franke, for example in the article ‘So much for size zero being out of fashion: model Bette Franke looks painfully thin during New York show’ (Leonard, 2013).

It seems that the fashion industry, by using models, decides which types of women are beautiful. This can put quite some pressure on ordinary women, considering that they maybe also want to be ‘beautiful’. All over the world, people are undergoing plastic surgery in order to change their appearance. Nowadays almost everything is possible, from leg lengthening and eyelid surgery to liposuction or butt implants. At the same time, there is quite some social media emphasis on the fact that every woman is beautiful just the way she is and therefore should not have to change in order to be beautiful.

Fashion dressed as judge

As revealed in this article, clothes are in fact a piece of discourse and give insight into someone’s identity. Hence, they reflect a specific order of indexicality (Blommaert, 2005), i.e., a certain symbol that points to a certain group of people in society. The idea that a woman’s body gives away part of her identity (e.g. that she is a Latina) might be based on stereotypes that people have of women from different cultures or ethnicities. In much the same way, clothing and dressing nowadays have the potential of creating identity as a general function (Entwistle, 2015).

Moreover, each society can have different images of the ideal woman. Although not everybody agrees with these images of a ‘perfect’ woman, the fashion industry does play a big role in the creation and maintenance of such ideals. This means that the fashion industry creates stereotypes of a beautiful woman, which can have as an effect that women who do not look the same way are excluded from being beautiful. This can lead to social pressure on women that feel the need to be included. Consequently, the way in which fashion is presented through the bodies and appearances of models can force women to look the same.

References

Bal Harbour Plastic Surgery (2011). Latina’s are changing the shape of beauty. Retrieved on 1 november 2016/

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A Critical Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Collins. (n.d.). Definition of Fashion. Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Dunlap, K. (1928). The Development and Function of Clothing. The Journal of General Psychology , 1 (1), 64-78.

Entwistle, J. (2015). The Fashioned Body: Fashion, Dress and Social Theory. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Kinsella, S. (1995). Cuties in japan. Women, media and consumption in Japan, 220-254.

Kramer, S. (2011). Het poldermodel: de Nederlandse vrouw is uniek. Amsterdam: Atlas-contact

Leonard, T. (2013, September 13). So much for size zero being out of fashion: model Bette Franke looks painfully thin during New York show. Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Listal (2013). Female Ulzzang. Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Loenen, C. (2011). Appels, peren, planken & zandlopers. Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Ngai, S. (2005). ‘The cuteness of the Avant-Garde’, Critical Inquiry, 31(31), pp. 4–811.

Nittle, N.K. (2016). Five Common Latino Stereotypes in Television and Film. Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Reichard, R. (2013). Why Aren’t We Talking About the Curvy Latina Stereotype? Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Roach-Higgins, M., & Eicher, J. (1992). Dress and Identity. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 10 (1).

Urban Dictionary (2008). Ulzzang. Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Victoria Secret (n.d.). The sexiest bras, lingerie and women’s fashion. Retrieved on 1 November 2016.

Yoused. (n.d.). Paspop vrouw hoofdloos wit [Photograph]. Retrieved January 11, 2017.