Globalization within the current Pentecostal church

The Pentecostal church has come to gain souls and to achieve its goals for the whole world. When it comes to contemporary religious streams that grow increasingly, Pentecostalism, which is a movement in Christianity, is certainly among them. The term ‘Pentecostal’ derives from the account of Pentecost in Acts 2:4 where Luke describes how, on the day of Pentecost, those gathered in the upper room were filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak in other tongues (Willis, 2013). The event, which is to be found in the book of Acts in the Bible, describes how followers of Jesus got filled with a divine entity, named the Holy Spirit, which brought supernatural capacities to the followers, of which one ability is described by Willis as ‘speaking in tongues’, which is a divine language of communication between God and a human being.

Present-day Pentecostals practice their faith, in accordance with the event on the day of Pentecost, relying on the Holy Spirit. When considering Pentecostal history, it quickly becomes clear that there’s an imperialistic drive behind the Pentecostal endeavors. Time has shown how the Pentecostal church ambitiously has been opting for a global spread of its ideologies. This article will measure how we are able to detect globalization in the present-day Pentecostal church.

In finding out to how the notion of globalization is implied in the current Pentecostal church, this paper will focus on defining the global cultural flows of Pentecostalism. Arjun Appadurai (1996) introduced five dimensions of global cultural flows, namely: ethnoscapes, mediascapes, financescapes, ideoscapes, and technoscapes that in total prove the presence of globalization. In the following, every dimension will be linked to practices of the Pentecostal church, to argue eventually that globalization does take place in present-day Pentecostalism.

The Ethnoscape of the Pentecostal church

By ethnoscape, Appadurai (1996) means: "the landscape of persons who constitute the shifting world in which we live; tourists, immigrants, refugees, exiles, guest workers, and other moving groups and individuals constitute an essential feature of the world and appear to affect the politics of (and between) nations to a hitherto unprecedented degree".

The landscape of persons who constitute the shifting world within the Pentecostal movement consists in general of traveling Pentecostal church leaders, who gather in meetings or conferences all over the world, and Pentecostal believers, who are willing to travel to attend church services and conferences. In the case of Pentecostal church leaders, many engage in crusades, which are big rallies that allow believers/non-believers to come together to worship God and to experience his power. Pentecostal leaders will then come to reach the masses through their preaching and healing services.

Figure 1: Prophet T.B. Joshua leading a crusade in the Azteca stadium in Mexico

Pentecostal crusades, which are widely promoted often fill up complete arenas and big conference halls all over the world. Church leaders that regularly lead crusades, acquire big names and statuses. In the present day, Pentecostal church leaders like Benny Hinn, T.B. Joshua, and Chris Oyakhilome have been creating a mass following globally for some time, meaning that their displacements motivate many believers to travel after them, as the believers wish for healing or deliverance. In this respect many aspiring visitors have become eager to leave their homes and travel large distances, to encounter the works of the Holy Spirit through the Pentecostal church leaders.

What also really shapes the ethnoscape of the Pentecostal movement is the principal idea behind the movement’s strategies. Pentecostals place evangelization at the top of their principles, which is linked to a premillennial eschatology (Deininger, 2013). The evangelization of Pentecostals certainly has yielded results globally, considering that the Pentecostal movement was founded in 1906 during the ‘Azusa street revivals' in Los Angeles (Willis, 2013) and now heads for a number of over 800 million believers by the year 2025 (Barrett and Johnson, 2004). In short, it is safe to say that the Pentecostal movement has a plausible ethnoscape going on globally.

The Financescape of the Pentecostal church

According to Appadurai (1996), financescapes illustrate: "the very complex fiscal and investment flows that link economies through a global grid of currency and capital transfer." Many are convinced that the views of Pentecostals regarding finance are partially determinant of the movement’s appeal to the outer world. According to Christopher Marsh and Artyom Tonoyan (2009), Pentecostals have very much succeeded in attracting followers because of their attitudes toward financial responsibility and economic entrepreneurship in general. Marsh and Tonoyan (2009) go on to argue the following: 'For many people, (neo-)Pentecostal and charismatic churches have become social and economic ‘’micro-environments’’ where their economic and financial ambitions are not only frowned upon but are actively encouraged. What sets these sorts of micro-environments apart from others is that financial prosperity is not an end in itself, but is animated by a higher goal, the financing of God’s work on earth and more specifically contributing to the evangelization of their respective communities, cities, regions and so on.'

Pentecostals have very much succeeded in attracting followers because of their attitudes toward financial responsibility and economic entrepreneurship in general

This statement points out that Pentecostals are convinced, that the financial capital which flows in the Pentecostal financescape serves a higher purpose, which is the offer of support for God’s work on earth. Timothy Clynick and Tshepo Moloi (2006) give more insight into the thinking on finances, within Pentecostalism. They point out the notion of a term such as ‘classic marketplace Christians,’ which describes: "the individuals who believe that they have been anointed to minister in the workplace. This means that they have been chosen and empowered by the Holy Spirit for a divinely sanctioned assignment, which is bring transformation to their jobs and then to the marketplace as a whole. ''Transformation''’ implies that both ministry and occupation are dedicated to divine service to ''bring the Kingdom of God'' to the heart of the city."

Figure 2: Board of Trustees’ Report of the KICC.

Zooming out from the individualistic approach to finances in Pentecostalism teaches us that the separate Pentecostal churches also engage in financial activities for their environmental improvement. The latest Board of Trustees’ Report of the Kingsway International Christian Centre (2018), which is a church based in London, shows how a local Pentecostal establishment can strive to affect the local economy as well as the global economy, pointing out the fact that the KICC partners with some development projects in Asia and Africa (see Figure 2).

The Mediascape of the Pentecostal church

Appadurai (1996) describes mediascapes as follows: "mediascapes, whether produced by private or state interests, tend to be image-centered, narrative-based accounts of strips of reality, and what they offer to those who experience and transform them is a series of elements (such as characters, plots and textual forms) out of which scripts can be formed of imagined lives, their own as well as those of others living in other places."

With its aim of reaching the entire world, the Pentecostal church does not back down from the technological developments in modern-day society. Au contraire, the Pentecostal church excels at constructing its autonomous mediascape by making use of various media. A prime example of how a Pentecostal church can apply media in its endeavors is shown in the way the KICC handles its media outlets. In its Board of Trustees’ Report (2018), the KICC states the following: "Winning Ways is a major KICC outreach program that encompasses both print and electronic media, including radio, television and internet streaming. God has appointed KICC with a holy mandate to reach a dying world with the Living World. Through our international television and radio ministry Winning Ways, KICC has become a church without walls, taking the gospel to Europe, Africa, the Caribbean, the USA, Asia and the Middle East." This is a perfect example of how a local church can set its aim at reaching the globe so that people in different parts of the world can have an impression of how the KICC conducts its services.

Figure 3: Twitter page of pastor Joel Osteen

The emergence of social media has been beneficial for the Pentecostal church in its attempts to grow its reach as well. Platforms like Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram have proven themselves as valuable intermediaries, for Pentecostal churches to build interaction with their following. The Lakewood church, led by Joel Osteen can be seen as an example of how a church can exercise its influence worldwide, by making use of social media. The church maintains accounts on Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Instagram, while it utilizes three separate personas in addressing the general public. The first persona is that of Joel Osteen’s Facebook account which possesses 21 million followers; his Twitter account possesses 9.2 million followers along with his YouTube account which boasts a number of 1.1 million subscribers.

The Technoscape of the Pentecostal church

Pentecostals value the spread of information internally, to work towards a better functioning of their belief. That is why there are Pentecostal organizations, involved in providing formal education globally for aspiring Pentecostal leaders. This is related to Appadurai's technoscape which is defined as a "global configuration, also ever fluid, of technology and the fact that technology, both high and low, both mechanical and informational, now moves at high speeds across various kinds of previously impervious boundaries" (Appadurai, 1996). David J. Garrard (2002) notes: "the extent to which African Pentecostal groups will become involved in any sort of formal education will depend to a great degree upon the links they may have with western missions. This is because generally it has been Western missionaries who have been the advocates of this form of training. Formal training requires resources on a continuing basis which are often not available in many Indigenous Pentecostal groups. Resources here would include especially adequately trained personnel, finances and facilities such as suitable buildings, and libraries." This generally shows the importance of global solidarity among Pentecostal groups in order to guarantee the continuous exchange of technological information internally.

Figure 4: Church leader training by British organization 'Teso Development Trust'

However, there are marginalized Pentecostal groups, that are reticent about becoming involved in so‐called ‘advanced academic,’ stating that they have seen the tendency to lose the evangelical and Pentecostal emphasis of so many who have been trained in colleges based on the Western model (Garrard, 2002). This shows that a share of Pentecostal leaders is not necessarily convinced that the academic approach forms adequate church leaders, opting for the fact that one should only rely on the bible and the Holy Spirit to become a competent leader instead (Garrard, 2002).

The Ideoscape of the Pentecostal church

Appadurai refers to ideoscapes as: "concatenations of images, which are often directly political and frequently have to do with the ideologies of states and the counterideologies of movements explicitly oriented to capturing state power or a piece of it". In this respect Jean Comaroff (2014) zooms in on the situation in Africa, showing how Pentecostalism and politics can go hand in hand, arguing that Pentecostal themes of prosperity and deliverance themselves help to explain its widespread appeal to African nations. Comaroff (2014) explains that the appeal of Pentecostalism to many African countries resonates with two very distinct audiences on different sides of the socioeconomic divide. On the one hand, Pentecostal messages of individual agency and prosperity, attract many African elites while on the other hand, the Pentecostal messages set guidelines for avoiding evil and escaping poverty which offers hope to the destitute (Maxwell, 1998).

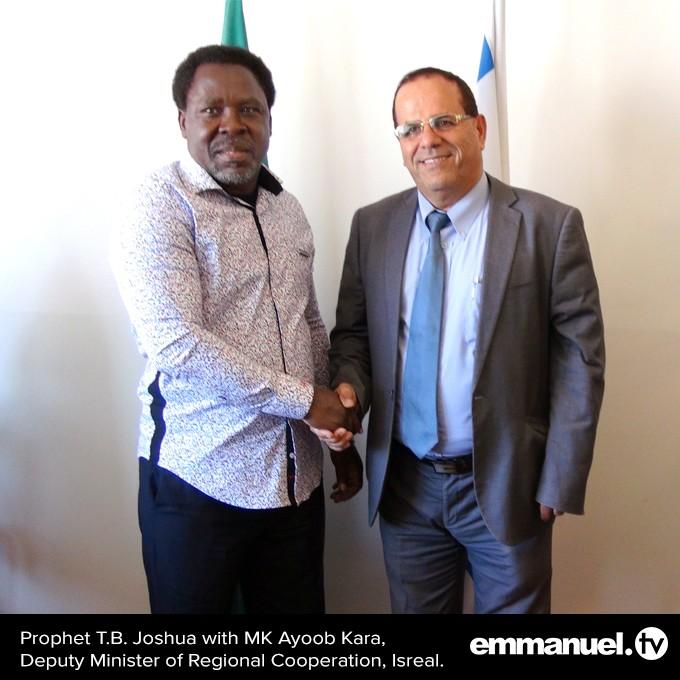

Through time successful Pentecostals have excelled at maintaining relationships with political authorities. Freston (1994) refers to the art of ‘time serving,’ which he describes as Pentecostal leaders remaining close to political figures regardless of ideology, offering services and prayers, while also participating in public ceremonies. In this light, international relationships between politicians and Pentecostal leaders have been built as well. Take for instance the bond that has been formed between the famed Nigerian Pentecostal Prophet T.B. Joshua and the Israelian state. Joshua has visited Israel on numerous occasions, meeting prominent Israeli dignitaries such as Minister of Tourism Yariv Lenin, Minister of Communications Ayoob Kara and Rabbi David Lau, the Chief Rabbi of Israel (Emmanuel TV, 2019).

Figure 5: Prophet T.B. Joshua (left) with Ayoob Kara Deputy Minister of Regional Cooperation, Israel

On the other hand, it’s also presumable that there are political forces, that are not too fond of Pentecostals. "In Ethiopia, for example, and in northern Nigeria and other areas with politicized Muslim-Christian relations, the Pentecostal Christian movement has faced government repression in the early part of the 21st century," says McCauley (2019). Mainly in Muslim countries chances are likely that political forces stand against the Pentecostal movement. The present situation in Algeria puts quite some emphasis on this. Algerian authorities have been forcing churches in the region of Tizi Ouzou to shut down recently (Shellnut, 2019). Pentecostals in Algeria have been under fire for over a decade. This is linked to a law that has been established in Algeria in 2006, which bans proselytizing (Grira, 2019).

The sustainability of the Pentecostal church

Appadurai (1996) made the remark that before the 20th century the two main forces for sustained cultural interaction were warfare and religions of conversion: "Few will deny that given the problems of time, distance, and limited technologies for the command of resources across vast spaces, cultural dealings between socially and spatially separated groups have, until the past few centuries, been bridged at great cost and sustained over time only with great effort".

While society has undergone great change through time, one might wonder whether a religious stream such as Pentecostalism still experiences great difficulty when pursuing worldwide expansion. The current activities in the various realms of Pentecostalism portray the level of swiftness present in the execution of Pentecostal ideals worldwide. The extent to which the Pentecostal church masters the required activities necessary in its distinct scapes, will determine the success of the church. While the current Pentecostal church directs its ethnoscape, financescape, mediascape, technoscape, and ideoscape, the Pentecostal church strives for sustainability in its global ventures. In short, the Pentecostal church might have had its battles while pursuing global expansion in the past, however, this current era of higher mobility certainly has proven to be beneficial for the Pentecostal church.

References

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity At Large: Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Barrett, D.B., & Johnson, T.M. (2004). Annual Statistical Table on Global Mission.

Clynick, T., & Moloi, T. (2006). Anointed for Business: South African ‘’New’’ Pentecostals in the Marketplace. Johannesburg: The Centre for Development and Enterprise.

Comaroff, J. (2014). Pentecostalism, “post-secularism,” and the politics of affect. Pentecostalism in Africa: Presence and impact of pneumatic Christianity in postcolonial societies, 15(1), pp. 221–247.

Deininger, M. (2013). Global Pentecostalism: An Inquiry into the Cultural Dimensions of Globalization. Hamburg: Anchor Academic Publishing.

Emmanuel TV. (2019, June 17th). T.B. Joshua to host meeting in, Israel.

Freston, P. (1994). Popular Protestants in Brazilian politics: A novel turn in sect-state relations. Social Compass, 41(4), pp. 537–570.

Garrard, J.D. (2002). “Tanzania”. In S.M. Burgess & E.M. Van der Maas (Eds.), The new international dictionary of Pentecostal and charismatic movements (pp. 264-269). Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan.

Grira, S. (2019, October 29th) Protestant church shut down in Algeria: 'They came bearing truncheons'.

Kingsway International Christian Centre. (2018). Board of Trustees’ Report.

Marsh, C., & Tonoyan, A. (2009). The Civic, Economic, and Political Consequences of Pentecostalism in Russia and Ukraine. Society 46(6), pp. 510-516.

Maxwell, D. (1998). “Delivered from the spirit of poverty?”: Pentecostalism, prosperity, and modernity in Zimbabwe. Journal of Religion in Africa, 28(3), pp 350–373.

McCauley, J.F. (2019). The Politics of Pentecostalism in Africa. In N. Cheeseman (Ed.), The Oxford Encyclopedia of African Politics.

Shellnut, K. (2019, October 17th). Algeria Forces Christians Out of the Country’s Largest Churches.

Willis, N. (2013). The Pentecostal Movement, its Challenges and Potential. Frankfurt: Peter Lang.