Hurricane Dorian: Making news out of breaking news

Hurricanes and other natural disasters typically attract a lot of media attention for reasons of safety. However, media coverage is rarely that uncomplicated. The case of Hurricane Dorian exemplifies how a hurricane’s coverage can also spark debate on sociocultural and political issues. In this case study, we provide an overview of how various US-based media sources fueled public debate through their coverage of Dorian. Specifically, we focus on controversies that started around Dorian concerning the immigration-environment nexus and issues of truth and authority originating in presidential tweets.

When hurricanes hit the media

People are generally familiar with the breaking news media format. Reportage follows an (unexpected) singular event live until the occurrence is over. After that, the aftermath and its effects become breaking news and the event gets reconstructed like a puzzle.

Since hurricanes develop constantly over a period of time, the media follow them for as long as they do, tracking them like an escaped morphing beast with headlines like “Tropical Storm Dorian roars to life, takes aim at Caribbean.” Such coverage is based upon meteorological predictions with live updates on the hurricane’s actual impact. Live camera footage is also often used to provide a sense of the hurricane closing in.

As the hurricane develops out of existing weather phenomena called a system, the news adapts to this. At first, the system that became Hurricane Dorian was only a small part of news weather reports since it had only a 20% chance of developing into a hurricane. When Dorian finally approached as a hurricane and the threat became more of a reality, only then did the media report on it in the format of breaking news.

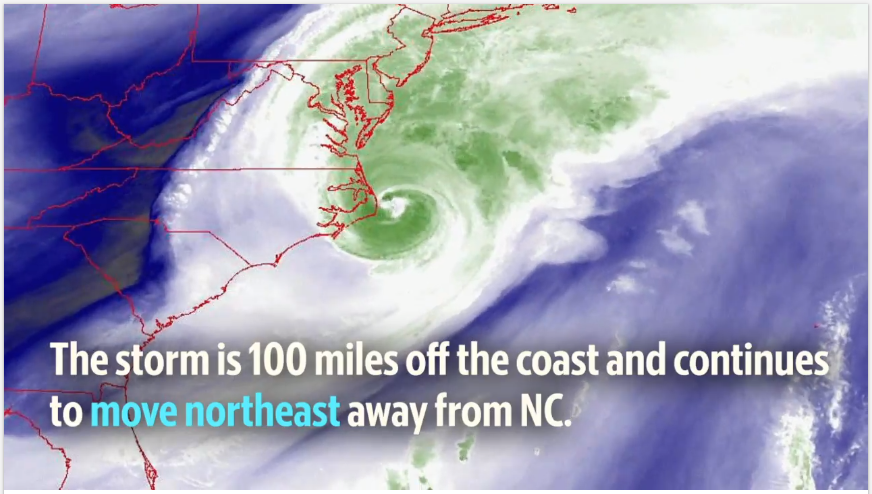

Still of video showing satellite images of Dorian

Suddenly, articles were made solely on the hurricane while previously news on Dorian would have been part of bigger weather reports. Instead of having a meteorologist explain the phenomenon in a video fragment, viewers were now increasingly presented with video footage of satellite images. Short clips showed the storm moving in a video format consisting of satellite images with written commentary edited onto them.

In the example above, keywords were highlighted and eerie music was used by the editors to underscore the impact of the hurricane. In this way, instead of being primarily informative like standard weather reports, breaking-news coverage is characterized by a notable shift in the presentation of information. This shift aims at constructing a story that is attractive to viewers through the use of various resources such as eerie background music to convey a sense of danger and threat.

Given the scarcity of primary sources, a hurricane brings a tornado of media reports not only on the event itself but also on related topics surrounding the hurricane’s occurrence.

One of the reasons behind this shift is that information is still lacking at this stage. Early reports are short and offer limited information. Journalistic texts are essentially clusters of references and quotes from forecasters and meteorological research institutes like the National Hurricane Center. A range of news channels rely on these same sources, which leads to much explicit intertextuality in such reports.

Given the scarcity of primary sources, a hurricane brings a tornado of media reports not only on the event itself but also on related topics surrounding the hurricane’s occurrence. In what follows, we outline how limited sources on events around a hurricane can be framed by media outlets in ways that spark controversy.

Dorian hits the immigration-environment nexus

Media coverage of Hurricane Dorian’s aftermath gave rise to heated debate in the immigration-environment nexus. This nexus represents the intersection between environmental debate (climate change activists vs. climate change deniers) and the immigration debate, which revolves around the US government’s stance towards refugees and asylum seekers.

In terms of environmental debate, the coverage of Dorian’s mere occurrence took two discernible paths in mainstream media outlets. Channels following the rhetoric of the scientific community, which views human activity as the leading cause behind climate change, framed Dorian as being a consequence of this. As a response, channels supporting the far-right notion of climate change being an expensive hoax regarded this framing as scaremongering.

The immigration debate started taking shape after Dorian hit the Bahamas leaving 70.000 inhabitants homeless. When, on September 9, a ferry with hundreds of Bahamian evacuees on board was getting ready to depart for the US, an announcement was made ordering anyone without a US visa to disembark. 130 people did so in confusion: Bahamians typically only require a passport and a clean criminal record to access the US. Aboard the ferry was also WSVN 7 reporter Brian Entin, who reported on the incident live via Twitter. One of his tweets showing a video of Bahamians leaving the ferry reached viral status with more than 33.000 retweets and over 5 million views.

Brian Entin's viral tweet

This tweet jumpstarted much controversy around allocating blame. The US Customs and Border Protection and the ferry company blamed one another for the confusion caused. President Trump responded to the incident saying that the US has to be “very careful” lest “people that weren’t supposed to be in the Bahamas […] including some very bad people" enter. He added that—“believe it or not”—many parts of the Bahamas were not hit by the hurricane, suggesting that the homeless should be moved to the untouched parts of the islands.

From “visa mix-ups” to climate apartheid

Entin’s video quickly became an intertextual object used as a main source by various journalists. While some outlets downplayed the event calling it a “visa mix-up,” others framed the incident as “senseless cruelty” to express indignation. Additionally, Trump’s statement was interpreted as implying that the humanitarian need in the Bahamas was not that great and that letting in refugees without proper background checks could result in “very bad people” taking advantage of the situation.

In line with the left-wing media climate discourse introduced above, the following frame has now emerged: Hurricane Dorian is an example of climate change and 70.000 Bahamians are now climate refugees. The Bahamas, with their small carbon footprint, are a victim of the pollution from countries like the US, which makes this situation an example of climate apartheid. Since the US is not welcoming the refugees on xenophobic grounds, we can see how issues of climate change and its effects become blended with a new extreme-nationalist anti-immigration movement. This movement comprises a curious fusion of white supremacism, xenophobia and environmentalism, with its main position being that nationalities are bound to their physical lands and that the presence of different nationalities in one nation-state should be averted. (Observe that, among others, the mass-shooters of Christchurch and El Paso identify as ecofascists; i.e., the radical branch of this new blend).

What we see here is how a breaking-news story originating in a tweet was framed by the media in diverse ways that initiated public debate on controversial topics. All this started with just one primary source on the aftermath of Dorian with the hurricane itself being quickly forgotten as immigration policy came into focus.

#sharpiegate: When Dorian hit Trump’s twitter

On September 4, President Trump presented a chart of Dorian’s expected route during a White House press briefing. In an act not only bizarre but also illegal, the chart appeared to have been altered with a black ink marker, a sharpie, so that Alabama would be in the zone of expected impact. This event generated a controversy now known as sharpiegate. Much like the Bahamian evacuees incident, this issue also started with a breaking-news tweet.

On September 1, Trump tweeted that a number of states—including Alabama—would be hit by Dorian harder than anticipated.

Trump's September 1 tweet

This tweet did more than it might seem initially. For one, the President was breaking the news that parts of the US were predicted to be hit by a hurricane. At a stage of uncertainty, the President’s social media (instead of a mainstream media outlet) became a channel through which new information was made available to the public. At the same time, with this tweet, Trump was constructing for himself an identity of “concerned President.” Like every act of communication made in a given time and space governed by a set of norms (in theoretical terms, a given chronotope), this tweet was also an act of identity (Blommaert, 2017). By tweeting this, Trump presented himself as a caring President on his Twitter account, which he has characterized as "his voice."

Interestingly, Trump's concern was also conveyed in the details. When people communicate something, we expect that the way they communicate it will “match” the information they are dealing with. The language (and other resources) used in a message are linked to the social content of the message in a process called iconization (Irvine & Gal, 2000). In these terms, there might be some expected iconicity surrounding a message (Blommaert, 2005). Here, the President’s delivery of such grave news (a hurricane hitting the US) should be paired with an expression of concern in some form—and it is. Mentions of the gravity of the situation escalate from hedged forms (“most likely,” “(much) harder”) to more alarming statements (“one of the largest hurricanes ever," “Already category 5”) forming a crescendo. This all culminates in advice and a wish typed in capitals and with exclamation marks, both markers of intensity.

Still, it would appear that the tweet’s content, not its form is what generated controversy. Contrary to the tweet’s claims, Alabama was not predicted to be hit according to the latest official information. In fact, 20 minutes later, the National Weather Service (NWS) bureau of Birmingham, Alabama published another tweet clarifying this as an answer to calls and messages received from the public.

The NWS tweet providing clarification

In the following days, Trump never backed down from his initial statement, insisting that he was right about Alabama. Instead, steps were taken to support the President’s false claim, including: the sharpiegate briefing, a series of tweets citing outdated maps as supporting evidence, a supporting statement by the White House, and—perhaps most strikingly—an unsigned statement issued by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA, NWS’ parent organization) which disowned the NWS tweet that contradicted the President.

These events were extensively covered by the media as the sharpiegate controversy. The NOAA statement in particular was heavily criticized by experts, who interpreted it as either grossly scientifically misguided or coerced. The overall critique of the attempts to support Trump’s claims led to the construction of a negative ascribed identity for Trump which was quite the opposite of who he tried to be through his tweet (Blommaert, 2017). From "concerned President," Trump was now being painted as a reckless, misleading and arrogant President. This negative ascribed identity was constructed by the “Fake News” Trump mentioned in his every sharpiegate tweet. Trump-favorite Fox News, who still recognized the falsity of Trump’s initial claim, argued that other media outlets were holding a “petty” grudge to smear Trump’s image. In the end, the controversy was less about the initial tweet’s content and more about how the tweet constructed a positive identity for Trump, which came under fire once the tweet’s content was fact-checked.

Truth, power and sharpies

The sharpiegate controversy points to important issues concerning truth and power. According to Haugaard (2012), in modern societies, truth (more than, say, God or tradition) is considered the final point upon which authoritative claims can be based. Scientists, for example, draw their authority from their qualifications, which are linked to the pursuit of truth through education. Democratic governments consult experts and provide logical arguments for their decisions. In this way, truth has “linked itself to the authoritative power of the state” (ibid.). So, truth helps solidify the authority of social agents (e.g., scientists, politicians) since we perceive it as being beyond convention: truth is truth, period.

Similarly, on a smaller scale, truth can also empower a message and, thereby, its conveyor (Haugaard, 2012). Besides being an expression of concern, Trump’s September 1 tweet included truth claims, which made it land stronger: the President was not vaguely concerned, his concern was based on facts (breaking news!). In this case, however, this appeal to truth backfired. Experts, from their position of authority, immediately exposed it as untrue leading to an adverse result for Trump’s perceived identity.

The subsequent sharpiegate events took things a step further. In an attempt to bring truth back on his side, the President framed journalistic fact-checking as “phony” before issuing an official document (the White House statement) and possibly ordering an expert-backed statement by the NOAA to support his claim.

Trump broadcasted inaccurate news on his twitter aiming to appear concerned and, when his claims were fact-checked, he made considerable efforts to bring the truth—and the power it entails—back to his side of the playing field.

President Trump’s problematic relationship with truth is no secret. In his campaign days, he strategically framed his political opponents as “threats to truth” as he did the media here. Then, on this occasion, Trump broadcasted inaccurate news on his twitter aiming to appear concerned and, when his claims were fact-checked, he made considerable efforts to bring the truth—and the power it entails—back to his side of the playing field.

Sharpiegate is problematic in that it goes against the principle of “science is science and facts are facts.” This would be alarming enough if that wasn’t also a Donald Trump quote from his presidential campaign. While scientific knowledge should be constantly challenged by new scientific findings, sharpiegate shows that its otherwise uncontested acceptability can be used by people to empower their authority through efforts to manipulate (scientific) truth. Perhaps most alarmingly, this can be an effective way to solidify one’s power if enough people ratify such practices (Haugaard, 2012). In this way, “alternative facts” can serve to generate authority while the authority of true facts is undermined.

In conclusion, Hurricane Dorian’s media coverage shows how a breaking-news event can be constantly rediscussed in the media to fuel debate on hot topics around it. It also highlights the importance of so-called “new media” like Twitter in shaping such storylines around a hurricane. While hurricanes strike the physical world, the digital world does not remain unphased. The controversies surrounding Hurricane Dorian we examined here, all largely Twitter-based, paint a picture of a world where knowledge and opinion are constantly contested on the digital plane just as much as—if not more so than—on the physical plane.

References

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse. A Critical Introduction. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert, J. (2017). Durkheim and the Internet: On sociolinguistics and the sociological imagination. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 173.

Haugaard, M. (2012). Power and truth. European Journal of Social Theory, 15(1), 73–92.

Irvine, J., & Gal, S. (2000). Language ideology and linguistic differentiation. In P. Kroskrity (ed.), Regimes of Language (pp. 35-83). Santa Fe: SAR Press.