Tilburg research on Mondrian in the New York Times

The New York Times published an article on cultural historian and biographer Léon Hanssen (Tilburg School of Humanities) who unmasked a Mondrian painting as being inauthentic, if not to say a fraud.

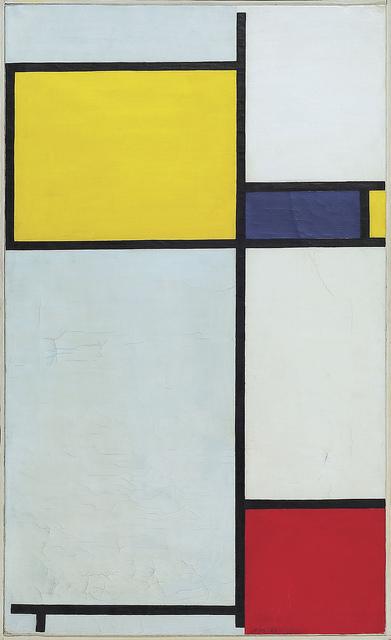

The whole story began as an accident. Léon Hanssen was conducting research for the second part of his Mondrian biography and his recently published ‘side-project’ with philosophical and personal essays on the famous painter: Alleen een wonder kan je dragen (Huis Clos, 2017). When he visited the Bozar Center for the Arts in the spring of 2016, he suddenly bumped into a Mondrian painting which seemed to be the untitled piece finished in 1923, which was considered to be lost ever since it was displayed at the Nazi-exhibition of “degenerate art” in Munich, 1937. Bozar had borrowed the painting from the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, which in turn borrowed it from an anonymous private collector in Switzerland.

The 'lost' painting of Mondrian

Could this really be the long gone Masterpiece made by Mondrian? Hanssen decided to make inquiries into the provenance of the painting. To cut short a long and thrilling story as exposed in Alleen een wonder kan je dragen and in a preview in NRC Handelsblad and a feature article in the New York Times: the work is not the painting which it seems to be. We even have to question if this is a Mondrian at all. Unfortunately the painting turned out not to be the masterpiece everyone, including Hanssen himself, wanted it to be. Nonetheless this decisive scientific falsification tells an important story of ignorance, opportunism and shadiness in the art world. In 1994 a Mondrian scholar by the name of Joop Joosten already examined the work and questioned its authenticity, but still the owner managed to exhibit the painting in various museums of modernist art.

On Monday last week, September 13th, Hanssen’s brand new book Alleen een wonder kan je dragen was presented in Spui25, Amsterdam. For this occasion, interviewer Laura van Gelder, who also published an interview with Hanssen in Univers, spoke with him about the main topic of the book: the image of Mondrian as a painter and a person. Hanssen criticized the image made of Mondrian today. Museum marketing turns him into some sort of a flashy networker, a cultural entrepreneur and even a womanizer. Hanssen argues that this romantic image with ‘like-ability’ may be correct for artists like Picasso, but doesn’t fit at all with the personality of Mondrian. He truly was a monk-like figure, who strived for a universal utopia, a pure aesthetic order to be found beyond the borders of the seeable and the knowable, in such a ‘sublime’ way that his art almost became dangerous, totalitarian and absolutist even. Thankfully, says Hanssen, he discovered that Victory Boogie Woogie (1944) needed to remain unfinished and chaotic, because this was the only way to counter his own desire for an eternal order which abandons and even annihilates the humane, and life as such.