When are you 'skater enough' in Eindhoven?

Skateboarders are a big part of the city of Eindhoven's life and can be found everywhere in the city. However, there seem to be specific places where they come together forming a community. In this article, skaters in Eindhoven will be looked at as a social group in the context of globalization and digitalization.

Ethnography in researching skaters

This paper will be focusing on the behavior of one specific group, which is why I adopted ethnography as the methodology to research Eindhoven's skaters. Ethnography is an approach in qualitative research that studies human behavior through observation and participation. To get a better understanding of the skaters in Eindhoven, I have had conversations with them and collected data through participant observation. I also spent a few days interviewing six skaters that self-identify as a member of the group. This data is useful for acquiring a better understanding of the bigger picture of what forms the group.

Since ethnography is mostly developed to study the behavior of groups in the offline world, I will go on to use another specific strand of this methodology too. Digital communication is becoming an important factor for the construction of social groups like skaters, and since traditional ethnography is mostly developed to study the behavior of groups in the offline world, I will use digital ethnography as a way of approaching online practices and communication (Varis, 2014). Digital ethnography is an effective method for getting insight into online communities (boyd, 2014). The fact that the researcher is not always in direct contact with the participant while doing online research, raises issues concerning the participants’ privacy – which I will take into account while researching the online identity of skaters.

The connection between the offline and online life of a skater is related to the fragmentation of the group into subgroups, as skaters within subgroups seem to be more connected online than skaters in general. A single online community that contains all skaters in Eindhoven does not exist, but most of them are somehow connected online. Besides the fact that they can follow each other on Instagram, I found great similarities in how they present themselves on this platform. For this reason, I have chosen Instagram as my digital research field.

Skaters as a social group

To look at the skateboarders in Eindhoven means to first look at what it means to be a skater. Most people seem to have an idea of what a skater is, mainly understanding the term as "a person that skates". But such a simple definition hides a more complex reality, which we will try to untangle. Looking at the definition given by Urban Dictonary (2004) is a good starting point for our investigation:

"One who rides a skateboard and has fun doing it. Skaters can be any kind of person; punk, prep, jock, criminal, nerd... whatever. Skateboarding has room for all kinds of people, and most of us won't discriminate based on anything but your love for skateboarding.’"

Embracing the values of the group is essential in the process of becoming an authentic skater.

In this definition, skaters are described as a heterogenous group that mainly focuses on the one thing they have in common, that being the passion for skateboarding, rather than focusing on their differences. A member of the skater group can simultaneously be a member of a different group with different norms, which gives skaters a layered and dynamic identity. People are now increasingly able to contain such a dynamic life-project of complex micro-hegemonies (Blommaert & Varis, 2013). Skater culture can be described part of these micro-hegemonies, on both a local and global level.

The career to being an authentic member

As Becker (1963) points out, all social groups make rules. These rules form a micro-hegemony, which is “the multiple sets of norms that govern the detail of social life" (Blommaert & Varis, 2011). People have to act following the skaters’ rules if they want to be a part of the group, and their behavior has to be accepted by skaters as conforming to these rules. Besides knowledge, one’s material and personal condition also play a role in becoming a member of the group. Embracing the values of the group is thus essential in the process of becoming an authentic skater (Beal & Weidman, 2003).

Figure 1: stereotypical skater clothing

Stereotypical skater clothing includes baggy trousers and t-shirts as well as a specific type of shoes that are associated with the skater community (see Figure 1). According to members of the community, this stereotypical idea still applies to the contemporary group found in Eindhoven. The skate store 100% Skateboardshop in Eindhoven (Figure 2) is regarded by skaters as a store that sells acceptable and authentic skater products, selling brands like Thrasher, Addidas, Vans, Dickies and Independent. The clothing that is considered authentic is thus brand-specific, but this does not seem to be the most important in a skater's identity. Clothes and shoes that have been worn by skateboarders since the 1970s have been picked up by the mainstream as a commodity nowadays. For this reason, clothing is not seen as the main emblem in the organization of a skater’s identity anymore.

Figure 1: 100% skateboardshop

One’s identity is a matter of enoughness (Maly & Varis, 2016); that is, identities are constructed out of a certain quantity of emblems. To research the amount of identity emblems that would be enough for a skater to be regarded as real and authentic among their peers, I interviewed several people who consider themselves a member of the skaters. When I asked skaters whether having a skateboard is enough to be a member of the skater group, the general answer was no. One of the respondents answered: “Having a skateboard is really not enough, skating with the skate mentality is a better way to describe skaters.” This answer looks similar to the addition we find posted to the definition of skaters on Urban Dictionary:

"However, since skateboarding has recently rocketed in popularity, it has now become ‘cool’. So now, you have to deal with those who are only doing it to be ‘cool’. These people are not really skateboarders."

One has to be a skater because they simply enjoy skateboarding, not for the sole purpose of belonging to the group.

This description suggests that intention is the most relevant aspect for those who want to be an authentic member of the group. One has to be a skater because they simply enjoy skateboarding, not for the sole purpose of belonging to the group. When "trying too hard", one loses their authenticity as it has been constructed by skaters who consider themselves "real". This notion of authenticity is constructed around the practice of skating, clothing related to skating, hanging at skateparks, and a specific mentality that makes one a skater.

Subgroups and their career

A career within a social group is defined as the “sequence of movements from one position to another in a system” (Becker, 1963); it can thus take a member a step further in the process of becoming a full member. Most of the respondents in my interview declared that they do see the skaters in Eindhoven as a social group but as divided into a variety of smaller groups. It is not a homogeneous group that shares the same norms although they often have certain common basic values (Beal & Weismann (2003). Subgroups have emerged within the group and becoming a member of such a subgroup can be considered as a part of a skater’s career. The phenomenon of subgroups indicates that skaters as a group have a certain polycentricity (Blommaert, 2005); that is, they gravitate towards different centers that provide different norms.

Figure 3: New shoes versus worn out shoes

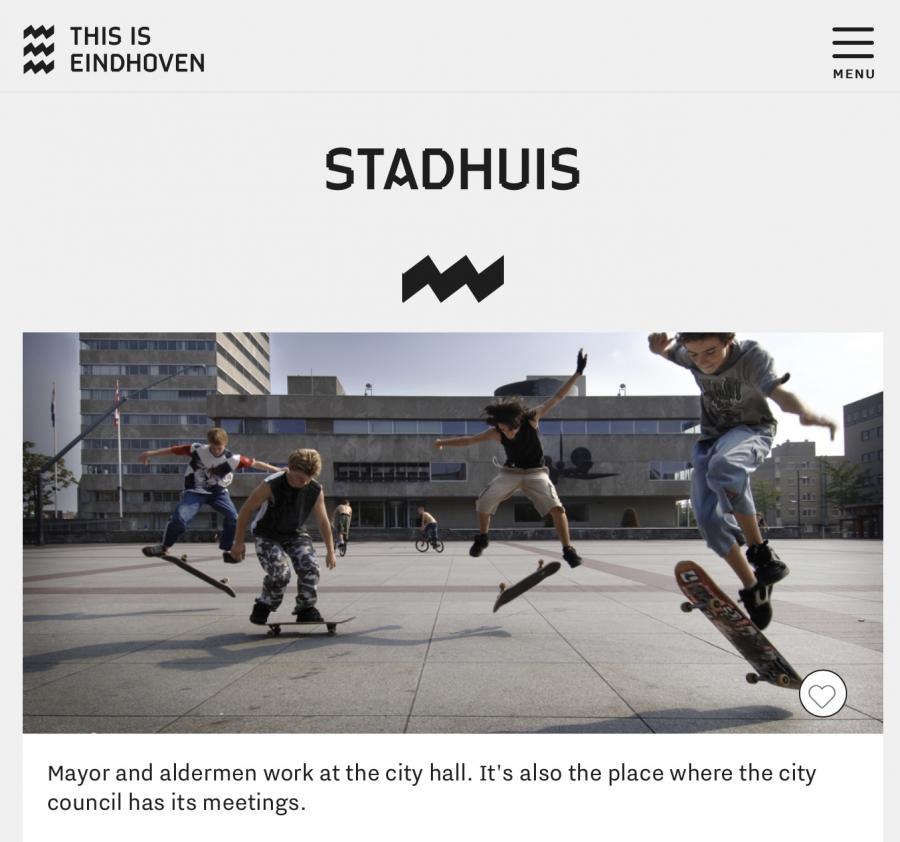

The division into subgroups is determined partly by personal preferences and partly by material conditions. One skater explained to me that some subgroups are striving for a more modern look than others, which is observable, for example, in the extent that their shoes are worn out (see Figure 3). Identity emblems like worn-out shoes can make one recognizable as a member of a certain subgroup. Besides that, belonging to a subgroup is also determined by the different locations of Eindhoven one is active in. The places that are commonly used by skaters to meet with fellow members are the town hall square (see Figure 5) and Area 51 (an indoor skatepark). Some of the skaters explained that they prefer the town hall square because Area 51 charges an entrance fee. Hence, besides the skater's personal preference, it can be concluded that a material condition like money also partly determines to which subgroup one belongs.

Creating an online identity

With every setting and post on a social media profile, one forms an online identity, which Sundén (1995) describes (in It's Complicated) as "people typing themselves into being''. In the context of Instagram, skaters mostly portray their identity in terms of pictures. All the skaters in Eindhoven that I interviewed post a good amount of (comparable) photos and videos with their skateboard (similar to those seen in Figure 4), clearly wishing to be recognized as a skater. The respondents claimed to not post this content to be seen as a real skater, but to show their tricks and skills with skateboarding. But as they also said before, intention – having a passion for skateboarding – is the most important identity feature for one to be a real skater. Besides that, the clothing worn in the posts also conforms to the identity norms mentioned above. The skaters might have an unconscious desire to be recognized by their peers as a real member of the (sub)group (or become famous and picked up by brands), as all posts within subgroups are quite similar.

Figure 4: #skateboarding on Instagram

Most of the skaters had an open account, making their content openly accessible for anyone to see. According to boyd (2014), some teens want to share their interests with their peers by granting unlimited access to their social media profile. When they want to post something on Instagram, they imagine an audience that is invisible in reality. The accounts that they themselves chose to follow is what they imagine their audience to be, but this does not mean that these accounts actually see their posts.

Skaters as a part of Eindhoven

Skaters in Eindhoven are part of a global niched culture while also having their own local features. Accounts that post content like that presented in Figure 4 act as crusaders on a global level, creating norms on what is "cool" and what not. But features like the skater shop in Eindhoven (Figure 2) add a local center of normativity. The skater identity is a subscription as they self-identity as a member of the group and also represent themselves this way (on the internet). But besides this subscription, the skater identity is also an ascription as the majority in Eindhoven sees them as a group. Even the city's official website shows their connectedness between the city hall square and Eindhoven's skaters, as seen in Figure 5.

Figure 5: web page city hall Eindhoven

It can be concluded that skaters are a dynamic and layered group, since their identity can be fragmented into different micro-hegemonies. The group can also be divided into subgroups, giving them a polycentric aspect as they produce different centers with different norms. Knowledge, material and personal conditions partly determine in which (sub)group one belongs. Physical identity emblems like clothing play a role in authenticity, but the notion of enoughness points to the intention of the skater as a major factor. Only skating to be a part of the group is seen as "fake" and not enough (even when wearing the right clothing). Members self-identify as skaters and also represent themselves in this way on their social media profiles. They wish to share their passion with peers as they form a community based on that passion.

References

Beal, B., & Weidman, L., (2003). Authenticity in the skateboarding world. Faculty Publications. Published Version. Submission 10.

Becker, H. S. (1963). Outsiders: Studies in the sociology of deviance. United States: Free Press.

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse: A critical introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert, J., & Varis, P. (2015). Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies; No. 139.

boyd, danah. (2014). It’s Complicated: The Social Lives of Networked Teens. United States: Yale University Press.

Karl (2004, June 29). Urban Dictionary: skateboarder. Retrieved on November 12, 2019,

Maly, I., & Varis, P. (2016). The 21st-century hipster: On micro-populations in times of superdiversity. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(6), 1–17.

Varis, P. (2014). Digital ethnography. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies; No. 104.

Vertovec , S. (2006). Emergence of Super-Diversity in Britain. Center on Migration, Policy and Society; No 25.