Watching #WitchTok: Do the Spiritual Content Consumption Habits of TikTok Users Corroborate Luckmann’s Theory?

#meditation, #astrology, #tarot and #wicktok (a hashtag for witches to share their knowledge and traditions); although TikTok is more well-known for its bite-sized lip-sync and dance videos, there are plenty of clips and hashtags for those who are interested in exploring their own spirituality. Some of these clips breach the barrier of nicheness and go trending, garnering thousands, if not millions of views.

The growing popularity of TikTok’s spiritual side coincides with a decrease in the percentage of Americans who identify as religious (Pew Research Center, 2015). At the same time, however, there is an increase in the percentage of Americans who identify as spiritual, but not religious (Lipka & Gecewicz, 2017). Americans who only identify as spiritual often practice this spirituality in an individualistic way; there is a lot of focus on the self, you are encouraged to do what feels good and it is not necessary to take part in traditional religious activity.

This trend of decreasing traditional religiosity and increasing individualistic, pluralistic spirituality, is a transformation of religion described by Luckmann. In this blog, the way users consume spiritual content on TikTok will be used as a case study of this transformation. Because its userbase is quite young, TikTok may provide us with insights into the development of religion in the future. Although I recognize that TikTok’s userbase consists of over 1.2 billion users from all over the world and that other parts of the world may see different religious developments, this blog will focus on North America which is home to 105 million TikTok users, making it the second biggest continental TikTok userbase (Iqbal, 2021). This is because there is a lot of data on America’s recent religious development and because I must limit the scope of this blog.

Luckmann’s Main Argument

Luckmann’s main argument is that, although there will inevitably come an end to the monopoly of Christianity, this does not mean that religion as a whole will end. “Instead, he maintains, a ‘market of ultimate significance’ emerges, where religious consumers shop for strictly personal packages of meaning that remain without wider social and public significance.” (Roeland et al., 2010, p. 290).

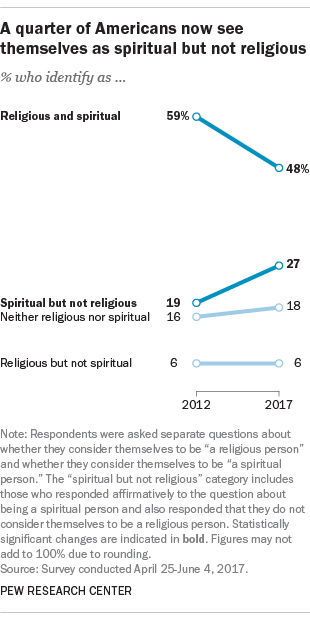

This trend is reflected in research done by Lipka & Gecewicz (2017), who found a sharp decline of 11% in the group of Americans who identify as both religious and spiritual. Although there is also a small increase of 2% of the group who identifies as non-religious and non-spiritual, the biggest increase can be seen in the group of Americans who identifies as non-religious, but spiritual. (8%). (See figure 1.)

Figure 1) Percentages of Americans who identify as religious and/or spiritual 2012-2017

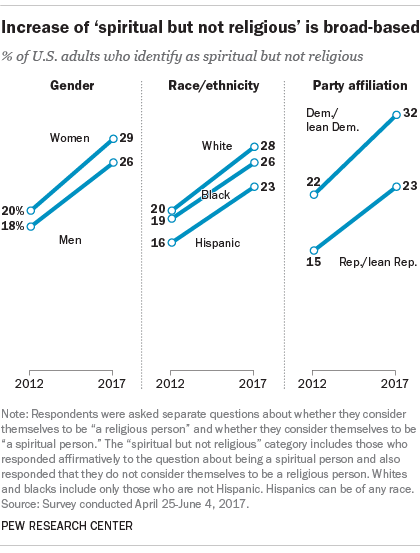

Not only is the increase in non-religious but spiritual Americans significant, but this trend is very similar across different social categories, such as gender, race/ethnicity and political party affiliation. (See figure 2.) Some groups, like the republicans, started out with a lower percentage of people, who only identified as spiritual, than other groups in their social category. But, the growth percentage of those who identify as non-religious but spiritual in these groups with a lower starting percentage is very close, if not equal, to groups starting with a higher percentage, which shows consistent growth across all groups of the percentage of people who identify as non-religious but spiritual.

Figure 2) Increase in U.S. adults who identify as spiritual but not religious across different social categories 2012-2017

This increase in spirituality goes paired with a decrease in the practice of traditional religious activities, which lines up with Luckmann’s idea that religious consumers will move towards a ‘market of ultimate significance’ where they will pick-and-choose practices and traditions of various origins to satisfy their spiritual need. For example, although 47% of American respondents in a study done by Gallup chose “strongly agree” to the statement "I am a person who is spiritually committed", only 13% responded "strongly agree" to all nine items on Gallup’s Spiritual Commitment scale, which measures involvement in traditional religious activities (Gallup, 2003).

TikTok as a ‘Market of Ultimate Significance’

TikTok is the perfect example of how this theoretical ‘market of ultimate significance’ “where religious consumers shop for strictly personal packages of meaning that remain without wider social and public significance” can work in practice (Roeland et al., 2010, p. 290). The first feed of content you see when opening the app is the For You Page which is comprised of a collection of personalised, recommended videos. These recommended videos are chosen by an algorithm that takes into account what type of videos hold your attention the most and what videos you engage the most with. The more videos you watch, the more accurately the algorithm can predict what content you would like to see more of. This leads to a highly individualized experience in which users are increasingly presented with topics that cater to their interests and are meaningful to them based upon conscious and unconscious decisions of content consumption.

There may be the danger that users will get stuck in a certain tradition or denomination and miss out on alternative streams of spiritual content due to this personalization. But, this seems not to be the case: “… rather than getting trapped in an echo-chamber, as you might with other platforms, TikTok’s For You page works to introduce you to new content creators that embrace new ways of thinking.” (Walker, 2020).

The openness of TikTok’s userbase to new ideas and the ability to spread spiritual ideas among groups of people who would not have come into contact with this content otherwise is also expressed by creators, like a creator by the name of Diaz: “I use TikTok as a very positive feed to spread love and spirituality in a way that connects with everyone, rather than a select few. The community is very open to other people’s beliefs and so far, I’ve had a very positive experience.” (Walker, 2020).

TikTok users’ consumption of spiritual content may be highly individualised, but does this also prevent the formation of community practices with a wider social and public significance? Very likely, yes. Not only are users separated in space and time while watching the same video, but TikTok does not provide many affordances for coming into contact with other users. However, partaking in trends or creating “duets”(this is a video response option with which creators can collaborate) may be activities in which meaningful communal practices can be created. Still, the formation of a stable community on TikTok is very difficult. As Partridge writes: “The user-oriented nature of the app makes the formation of stable communities virtually impossible inviting each individual user quite literally to conjure up their own hyper-personalised forms of spirituality.” (Partridge, 2021)

Conclusion

In line with Luckmann’s theory there has been a decrease in the group of Americans who identify as religious and spiritual and also a decrease in the practice of traditional religious activities. In its place has emerged a group of Americans who identify as spiritual but not religious and their spiritual practices have been individualistic and pluralistic. TikTok has been a great example of this trend towards a ‘market of ultimate significance’ as it provides users with a highly individualistic way of consuming spiritual content based on personal preferences, while also allowing for different spiritual ideas to be presented to users who may not be familiar with them. Lastly, TikTok’s lack of community shaping affordances makes it more difficult for meaningful communal practices to be formed.

References

Gallup, G. H. (2003, February 11). Americans' Spiritual Searches Turn Inward. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/7759/americans-spiritual-searches-turn-inward.aspx

Iqbal, M. (2021, November 12). TikTok Revenue and Usage Statistics (2021). https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/

Lipka, M. & Gecewicz, C. (2017, September 6). More Americans now say they’re spiritual but not religious. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/09/06/more-americans-now-say-theyre-spiritual-but-not-religious/

Partridge, E. L. K., (2021, September 6). When Spirituality Meets TikTok: Gen–Zs Answer to Religion. Theos. https://www.theosthinktank.co.uk/comment/2021/09/02/when-spirituality-meets-tiktok-genzs-answer-to-religion

Pew Research Center. (2015, November 3). U.S. Public Becoming Less Religious. https://www.pewforum.org/2015/11/03/u-s-public-becoming-less-religious/

Roeland, J. H., Aupers, S., Houtman, D., De Koning, M., & Noomen, I. (2010). The quest for religious purity in new age, evangelicalism and islam: religious renditions of dutch youth and the luckmann legacy. Annual Review of the Sociology of Religion, 1(1), 289–306. https://doi.org/10.1163/ej.9789004187900.i-488pp. 289-306

Walker, J. (2020, November 1). TikTok has become the home of modern witchcraft (yes, really). Wired. https://www.wired.co.uk/article/witchcraft-tiktok