Racism and the politics of the beach

It is the end of November and South Africans are getting ready for the summer holiday season and to go to the beach. Festive decorations are up in shopping centres around the country. Soon schools and universities will be closed, and annual bonuses will be paid out to those who are lucky enough to have employment. The feeling of enjoyment, of good times ahead, is captured in the commonly uttered phrase ke dezemba boss!, ‘guys, its December!’ – it is the one month of the year when everything goes!

Residents of coastal cities, and up-country visitors make their way to the beach: to Cape Town, Durban, Port Elizabeth and East London as well as to numerous smaller towns along South Africa’s shoreline.

Yet, the beach is not just a place of holidays and happiness. It is also a place, which reminds one of colonial violence and dispossession, of the past and its continuation into the present.

Space, racism and the settler-colonial project

In Racist Culture (1993), David Goldberg reminds us that racism is always instantiated in specific spaces, changing its shape – but not its dehumanizing and destructive force – through time.

Settler colonialism as a structure-of-domination is heavily invested in space. In settler-colonial societies – such as South Africa, Australia, Canada or the United States – questions of race, and racism, are linked to the land, its possession and one’s control over it (Aileen Moreton-Robinson, The White Possessive, 2015).

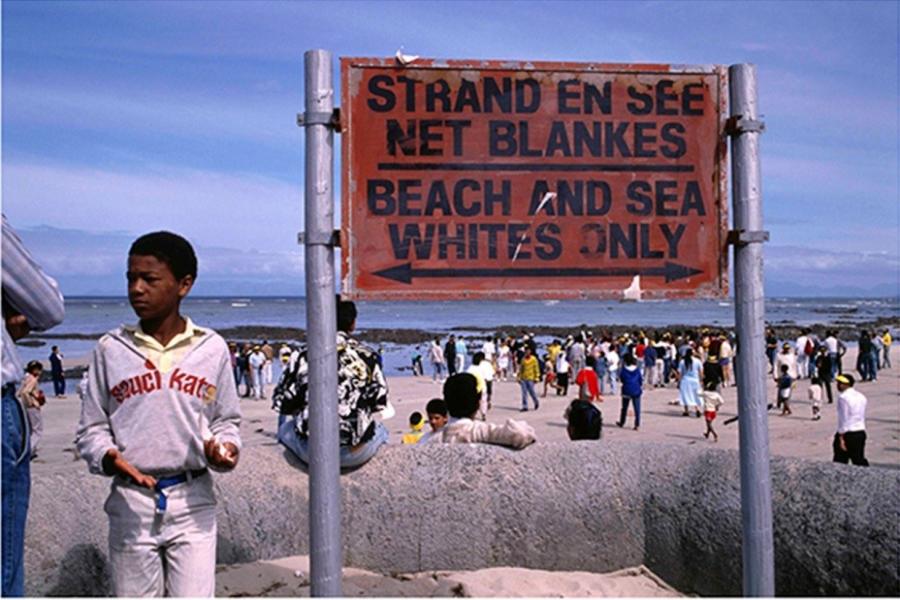

The apartheid state created, and legislated, racially structured experiences of space

South Africa’s apartheid laws – as a direct continuation of settler-colonial ideologies – were a blatant exercise in spatial control. The apartheid state created, and legislated, racially structured experiences of space: where one could live, work and spent one’s leisure time was dependent on one’s racial classification.

This included the beach and the ocean. The coastline was divided up into white, Coloured, Indian and Black beaches, with most of the shoreline and the best beaches reserved for whites.

Beach apartheid

In Cape Town, for example, whites had access to the sandy dunes of Bloubergstrand, the spectacular Atlantic coastline from Sea Point to Kommetjie, and the popular beaches and tidal pools of Simonstown, Fishhoek, Kalkbay and Muizenberg.

For those classified Coloured, only two small beaches were available on the Indian Ocean. Another beach was reserved for Indians, and the large African population of the city had but one beach: Mnandi Beach.

Mnandi is isiXhosa and means ‘nice, pleasant’ – yet the beach was anything but ‘nice’. Sindiwe Magona remembers Mnandi Beach in her autobiography Forced to Grow (1992) as follows: ‘Uninviting. Unappetising. Bleak and desolate. Barren. And not safe’.

The situation was similar in other coastal cities: in Durban more than two kilometres of beach were reserved for whites (at the time 22% percent of the population), 650 metres were granted to Africans (46% of the population), 550 metres to Indians (28% of the population), and 300 metres to Coloureds (4% of the population). The white beaches were safe, with public amenities, shark nets and lifeguards; the Black beaches were barren, unprotected and treacherous, often located next to sewage outlets (for details see, Jayne Rogerson, Kicking sand in the face of apartheid, 2017).

Beach apartheid was enforced strictly till the late 1970s, when slowly, during the 1980s, restrictions were relaxed and regular ‘beach protests’ challenged the whiteness of South Africa’s coastline. In 1989, beach apartheid was officially ended.

Race-troubles at the beach

Yet, the beach, now open to all, remains a troubled space in post-apartheid South Africa. It is an escape from the drudgery of work, and a space of relaxation and recuperation. It is also a space where the racialized practices of the past continue to be present, and whites, especially, reproduce the old patterns of apartheid. As noted by the South African journalist Ferial Hafajee: ‘Beaches are places of fun, but also of pain’ (I swim where I like?, 2019).

Consider the well-known case of Penny Sparrow, a Durban estate agent. In January 2016, she took to Twitter to voice her views. She posted an image of the crowded Durban beachfront on New Year’s Day, and called those celebrating the New Year ‘monkeys’, drawing on a long-standing racist trope of anti-black dehumanization.

The beach is part of the settler-colonial project and its white imaginary did not disappear with the end of colonialism or apartheid.

In December 2016 a resident of Hout Bay, an affluent seaside suburb in Cape Town, called Black beach dwellers ‘stupid animals’. 2017 started no better when African beachgoers at Amazimtoti, south of Durban, were referred to as ‘cockroaches’. A year later, Adam Catzavelos posted a video from a beach in Greece where – to his delight – he was among white people only. In his racist rant, celebrating the beach’s whiteness, he used to k-word (South Africa’s equivalent to the n-word).

There are too many incidents to list them all; they spring up with sad regularity around the holiday season, when the weather is hot and the beaches full. Howard Feldman, a South African social commentator, noted: ‘somehow it is a trip to the beach that seems to be the trigger for some South African racists’ (On white South Africans being racist on the beach,2018).

Settler colonialism and the beach

The beach is part of the settler-colonial project and its white imaginary did not disappear with the end of colonialism or apartheid.

Early South African beach culture self-consciously mimicked British seaside resorts such as Brighton, which too are embedded in ideologies of whiteness (Daniel Burdsey, Race, Place and the Seaside, 2016). The beach became part of the land that was settled: it was not just productive farmland that was desired, but also leisure and pleasure spaces. All land – and even the ocean – was claimed.

From the 1960s onwards Californian beach culture took hold, localizing a transnational aesthetic of abled white bodies, athletic and muscular, enjoying commercialized leisure culture in the sun.

Both imaginaries created distinct spaces of settler-colonial pleasure, and positioned Black beachgoers as ‘the other’, as those who striate – create stretch marks – in the imaginary smoothness of coloniality’s exclusionary spatialities.

Contemporary discourses and practices refract and reproduce past discourses. Central is a discourse of defilement and the violation of public space. Black manners are positioned as inappropriate for the beach; litter and noise the material manifestation of such inappropriateness. Moreover, there is the persistent fear of being ‘overrun’ by Black beachgoers, of losing control of the space one once upon a time so confidently occupied.

These are fears that were raised back in 1982, when the first integrated beaches were created, and the same fears are articulated today on social media platforms (Ana Deumert, The multivocality of heritage, 2017).

For others the response has been self-segregation: the exclusive possession of the seashore is affirmed either by avoiding the beach on public holidays, or by moving to beaches that are either private or not easily accessible to the many who rely on public transport (Leslie Bank, Frontiers of freedom, 2015).

Theoretical implications

Beaches in South Africa are predominately public, free for everyone to visit, without payment of a fee. The beach could thus be an equalizer, a place everyone can enjoy, where people from different walks of life can intermingle freely. And this could – if one believes in Gordon Allport’s (The Nature of Prejudice, 1954) contact theory – over time improve intergroup relations and reduce negative prejudice.

Yet, as the South African scholar Zimitri Erasmus has argued, sharing space does not end racism (Contact theory: too timid for “race” and racism, 2010). The reasons why contact theory does not work is its lack of attention to what Erasmus calls ‘the pathologies of white privilege’: ‘innocence, entitlement, denial, benevolent patronage, oppressive courtesies, and arrogance’.

To this one may add the more specific pathologies of settler colonialism, and the threat that Indigenous presence poses to the future of the settler-colonial project. Indigenous presence brings to the surface the settlers’ fear of their own dissolution once the violence of the past is acknowledged, and lands are reclaimed (Phil Henderson, Imagoed Communities, 2017).

The beach and the anticolonial struggle

Like the mangrove, the beach is a borderlands; it is land and sea, soil and water, always both, never just one or the other. There is a poetic to the beach, a poetic that links past and present in an imaginary that is not only that of white supremacy and settler coloniality, but also of anticolonial struggle and freedom.

In March 1975, two poems about the beach appeared in Sechaba, the official organ of the African National Congress. One poem, by Zarina Chiba, was titled ‘Migrant in my own land’, and reflected on beach apartheid: ‘Muizenberg Beach with its shocking blue sea/sundrenched/but denied to me’.

A few pages later the Jamaican poet Andrew Salkey writes about the beach too, yet with a different timbre, not of the present but of the future. His poem starts with the return of ‘the wretched’:

You should have seen

who struggled out of the sea,

today: a tired, rock-sliced

miner, with clogged pores,

who’d given up the race,

foxing them completely,

locking his hands into the sand!

And as the wretched arrive at the shore, the ‘Boer ghosts, scrambling, land-crazed, diamond-swipers’ understand ‘deep down’ that ‘they’ve got to hit that southern water’ and ‘swim all the way out, to the wide, quiet Antartic’.

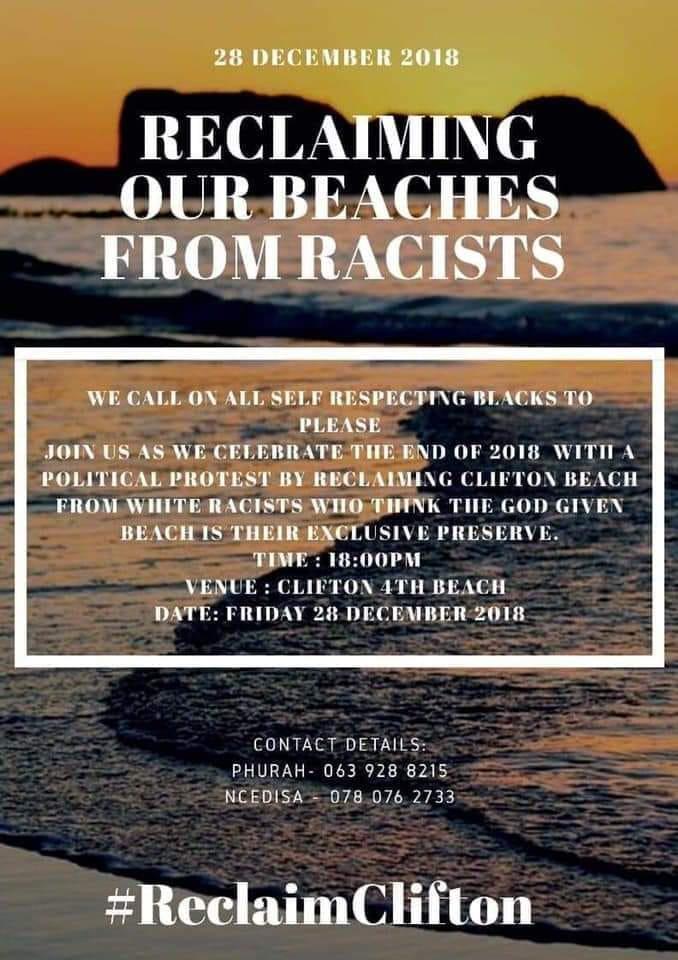

The poem is reminiscent of the prophesy of uNongqawuse, where it is said that the ‘ancestors … will rise from the dead after we have killed our cattle. They will emerge from the sea’ (Zakes Mda, Heart of Redness,2000). It also brings to mind the ritual slaughter of a sheep at Clifton Beach in Cape Town. This was done – in December 2018 – to cleanse the beach of its racist past, and to allow for new futures; futures that are located outside of the settler-colonial imaginary.

The beach is past, present and future.