The Pulp of Forbidden Fruit

Last weekend, the annual Boekenweek started, a ten-day event that supports the promotion of Dutch literature. This year’s theme: forbidden fruit. While the hedonistic nature of the human species is a recurrent subject of investigation in literature, we can wonder if the novel is still capable of being truly controversial these days.

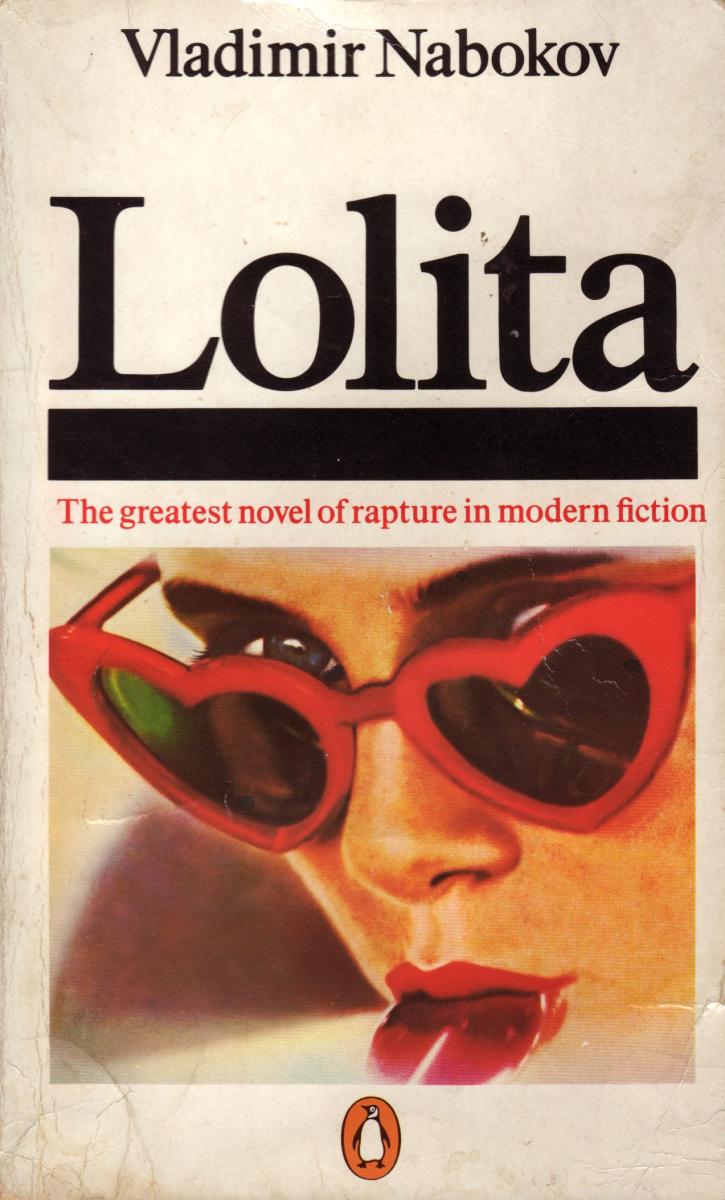

Without discomfort we can dive into the sexual explorations of Constance and Oliver in Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, enjoy the well-written but inappropriate relationship between Humbert and Dolores in Nabokov’s Lolita and even the sadomasochistic porn that marks the whole oeuvre of de Sade can now be read as an embodiment of the philosophy of the Enlightenment (see: Horkheimer & Adorno, 1972). Hidden under the veil of ‘Literature with the capital L’, the sweetness of forbidden fruit can now be tasted with the excuse of an aesthetic experience.

Lolita by Vladimir Nabokov, 1955

The choice of theme seems to display a yearning desire for a time in which literary sins were traded under the counter by human beings that would look each other in the eye. And even if most of the controversial works of the last few centuries became legal products, the gaze of the ‘Other’ while purchasing these secret pleasures used to be undeniable. The anticipatory pleasure of flipping through the pages of a controversial novel in the back of a bookstore, buying it with flashes of excitement on your cheeks and biking home with the pages burning in your bag all used to be important parts of the charm.

In the digital world, the ‘Other’ has become a faceless screen that shows us what we want, whenever we want it. The door to the paradise before the fall of men seems to be open for all those who have access to the Internet. In the age of both accessibility and anonymity, the picking of forbidden fruit has therefore become a less thrilling activity since nobody is there to witness it anymore. Furthermore, our most extreme fantasies are just one click away, which transformed the exciting bike ride home into a tedious short cut.

The anticipatory pleasure of flipping through the pages of a controversial novel in the back of a bookstore, buying it with flashes of excitement on your cheeks and biking home with the pages burning in your bag all used to be important parts of the charm.

While the actual act of reading has always been a solitary one, its conditions seem to have changed. Susan Sontag wrote in 1996 that the age of screens marked the beginning of the ‘death of inwardness’. In her letter to Borges she states: ‘when books become “texts” that we “interact” with according to criteria of utility, the written word will have become simply another aspect of our advertising-driven televisual reality.’ (2002, p. 112). This ‘democratic’ future of literature would mean nothing less than the end of true self-transcendence, according to Sontag.

Twenty years later, her statement could be filled in with “quotes” instead of “texts”, and “shareability” instead of “utility”. While the Internet still offers an obscure, underground space in which our darkest fantasies can wander freely, the upper layers of the web – the ‘social’ platforms – became places of excessive visibility; of sharing, liking and putting ones interests out there for the world to see. The screen is no longer just a faceless gate that will bring us to hidden areas without being seen; it is also a reflective mirror of (often invented) personas.

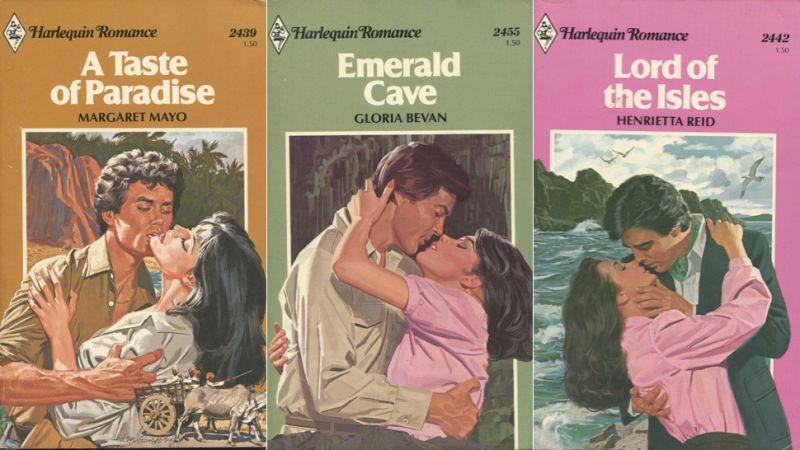

The Harlequin Romances

We became what we like and liking the new translation of Anna Karenina is one of the least scandalous moves we can make these days. In stead, we should climb upon our bikes again, go to the nearest bookstore and search for the real guilty pleasures of our time. The endless boy-gets-girl stories in Harlequin romances, the adventures of supernatural shenanigans in science-fiction pockets and the incestuous scenes in endless fantasy series are all waiting for us to be picked. Instead of searching for the literary forbidden fruit, we should look for its juicy pulp. That would be a truly provocative theme.

References

Horkheimer, M., & Adorno, T. W. (1972). Dialectic of enlightenment. New York: Herder and Herder.

Sontag, S. (2002). Where the stress falls: Essays. London: Jonathan Cape.