Native Advertising: distinguishing promotional from editorial content

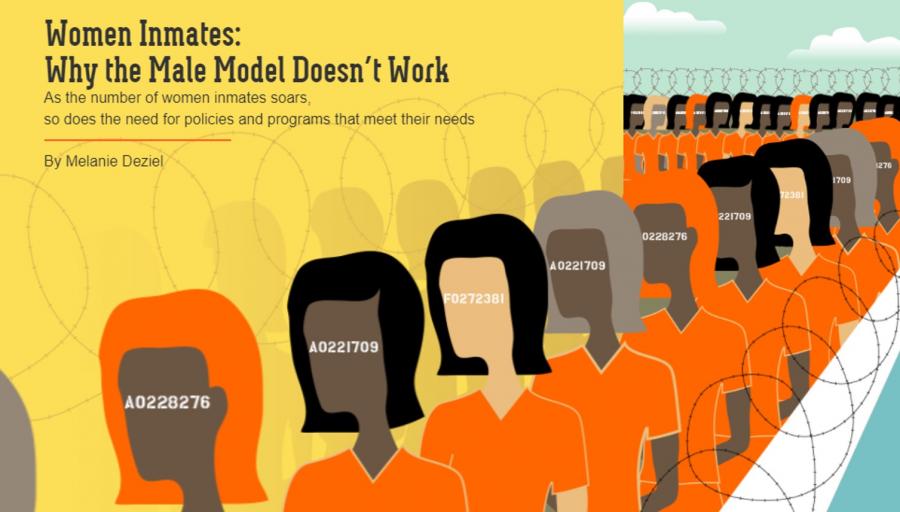

Back in 2013, the New York Times published an article that would later become a staple in native advertising practice. The article reported on the challenges faced by female inmates when serving their sentence in prisons designed for a men. For example, it points out that there are 28 federal women’s prisons in the U.S., whereas the number of men’s prisons is almost three times higher. This means that sentenced women often end up far away from their families and unable to see them. The article also mentions a variety of facts, including that at least three out of four female inmates have been physically or sexually abused in their lifetime. In other words, the article is full of information and represents a balanced report by classic journalistic standards.

However, this article also doubles as an advertisement for the Netflix series Orange Is the New Black. Indeed, this is one of Netflix’s most famous series, and it has been widely successful. Although the name, plot, or production team involved in the show are not mentioned anywhere in the text, this article is considered one of the most notable examples of native advertising, both in academia and in practice. So what exactly is a native advertisement?

One of the visuals for the NYT native advertisement

Defining Native Advertising

Native advertising is the relatively new practice of presenting marketer’s content in a way that resembles editorial content. By using similar formatting and location features the marketer borrows the credibility of the content publisher (Wojdynski & Golan, 2016). The key objective of native advertising is therefore to unobtrusively and seamlessly blend into the medium that it’s found in. The Interactive Advertising Bureau states that most advertisers aim to deliver cohesive and platform-consistent paid advertisements so that the consumer thinks they are fully integrated (IAB, 2013). You have probably stumbled upon, or even engaged with, this type of content many times.

If you have ever read a BuzzFeed article, there’s a high chance that it was a native advertisement. BuzzFeed strongly prefers sponsored content as opposed to classic banner ads. There are numerous examples of native advertising that can be found on the website. From blatantly satirical quizzes like ‘Which type of donut are you?’ sponsored by Dunkin Donuts to the ‘Sunbathing: expectations vs. reality’ native advertisement sponsored by Cancer Research UK, these approaches are very effective and generate high engagement from readers.

Illustration for the Buzzfeed native advertisement

As it always is with online phenomena, there are a variety of different views on native advertising – both from researchers and consumers. Just like cases of conspiracy theories (ever more present in the time of a pandemic) or cancel culture, the reception of its ever-growing popularity has sparked a serious debate on how online users can be more savvy and thoughtful when engaging with sponsored content.

The consumer basically ‘has their guard down’ when consuming a native ad and therefore cannot critically think through reviewing or possibly buying the product.

The covert nature of native advertisements may cause readers to struggle to recognize the persuasive nature of an ad (Wojdynski & Evans, 2016). For some researchers this is seen as a potential issue and cause for concern, because the consumer basically ‘has their guard down’ when consuming a native ad and therefore cannot critically think through reviewing or possibly buying the product. The reason for this is grounded in the traditional role of journalistic media – to inform, deliver facts, and adopt multi-perspective reporting (Herrscher, 2002). That’s why, at least in theory, it’s assumed that consumers will believe that native advertising content gives a more neutral and balanced overview of the products, services, or people featured in the article (Ikonen et al., 2017; Wojdynski, 2016).

Digitalization as condition sine qua non

Aside from this compelling fusion of content that is typically seen in portals or print media, there are several other affordances that make native advertising so specific to the digitalized age. One of them is the adaptability of content to different social media networks. Both Instagram and Facebook, for example, serve embedded ads when you scroll through the feed – and sometimes the algorithm makes sure that the subject of an ad is exactly something that you were thinking about three days ago.

It is, therefore, no surprise that the marketers’ spending on native advertising grew about 65 per cent in 2016 and 50 per cent in 2017 (Mullin, 2018). With traditional advertising becoming less effective, this shift in practice is quite understandable. Native advertising is not the only newly adopted strategy – think of influencer marketing, for example. Here, it all comes down to the influencer’s trustworthiness and the number of followers or potential consumers they can reach.

The core premise of digitalization that there is no life without online presence serves us well in explaining the success of marketers’ efforts in approaching their targeted audiences unobtrusively.

Hence, the core premise of digitalization that there is no life without online presence serves us well in explaining the success of marketers’ efforts in approaching their targeted audiences unobtrusively. In a world where every ads success is measured through key performance indicators (KPI) such as engagement, reach, retention, or click-through rates (CTR), it is not hard to understand the role of connectedness in this phenomenon. Our phones and laptops serve as a medium for revealing our online persona, and they ultimately become an extension of our identity. Based on our likes and clicks, we get customized, tailored ads that try to cater to our interests. And sometimes, we become immersed in this experience.

Problematic Disclosure

This doesn’t mean, however, that marketers and publishers can get away with everything. Disclosure transparency is one of the most important factors in understanding native advertising. It is defined as the degree to which the consumer is made aware of a sponsored message's paid nature, as well as the degree to which the sponsor is disclosed in the message (Wojdynski et al., 2018). Although the construction of universal native advertising guidelines, and even more so their legislative implementation, are still in the early stages, research in this field points to a need for ethical considerations. Early guidelines and recommendations, such as those from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, state that “any qualifying information necessary to prevent deception must be disclosed prominently and unambiguously to overcome any misleading impression created” (emphasis added, FTC, 2015).

As with the label, the position of the disclosure may vary. In some cases, you might have to scroll all the way down to the end of an article to find out that it has been paid for by a third party.

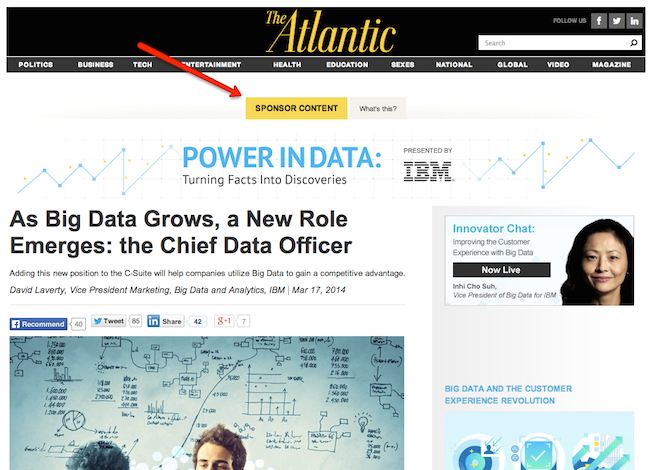

The conflicting roles of non-intrusiveness and manipulativeness have led researchers to closely investigate the nuances that separate effective from ineffective native advertising. A study by An et al. (2018) revealed that disclosures in native advertisements are generally ambiguous, and sometimes identifying the sponsor becomes problematic, as advertisers use different labels and terms. Indeed, when you look up sponsored content online, you find numerous variations on disclosure, placed in different positions. Some of the most-used terms are “sponsored post”, “paid post”, and “advertisement”. As with the label, the position of the disclosure may vary. In some cases, you might have to scroll all the way down to the end of an article to find out that it has been paid for by a third party.

'Sponsor content' as an example of a disclosure placed in a native advertisement

Native advertising and a consumerist future

In the age of ad blockers and ad-skipping, as well as prompt pop-up window closings, the emergence of native advertising is anything but surprising. However, the issue arises when you no longer know who to trust. Decreasing trust in media and publishers turning to marketers in search of profit are partly responsible for the digital landscape we currently find ourselves in. This is why “unbiased” or “honest” reviews have become embedded in online discourse: the word "review" no longer inherently connotes trustworthiness.

However, native advertising would not be so successful if there was no interest from consumers. It resembles tabloid culture in the sense that many people dislike it, but a large number of people consume it – often the ones that are the most critical of it. Clickbait titles and news that barely qualify as such are the result of the increasing demand, whether we like it or not. The same can be said of advertising. Many people will click away an advertisement sooner rather than later if it bluntly promotes the product. However, if advertising is attractively embedded into an article that aims to deliver facts or tell a story, the click-away rate is much lower.

Learning to deal with new forms of texts is crucial for achieving media and digital literacy. It is a continuous process rather than the skill we can at one point master. It is important to adjust our knowledge, understand the phenomena we constantly deal with online, and make responsible decisions for ourselves. Native advertising can be equally appealing and annoying, and it’s not going away any time soon.

References

An, S., Kang, H., & Koo, S. (2019). Sponsorship Disclosures of Native Advertising: Clarity and Prominence. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 53(3), 998-1024.

Federal Trade Commission (2015). Enforcement Policy Statement on Deceptively Formatted Advertisements.

Herrscher, R. (2002). A Universal Code of Journalism Ethics: Problems, Limitations, and Proposals. Journal of Mass Media Ethics, 17(4), 277-289.

Ikonen, P., Luoma-Aho, V., & Bowen, S. (2017). Transparency for Sponsored Content: Analysing Codes of Ethics in Public Relations, Marketing, Advertising and Journalism. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 11(2), 165-178.

Interactive Advertising Bureau (2013, December). The Native Advertising Playbook.

Mullin, B. (2018). Native advertising growth projected to slow; research firm eMarketer expects most of the growth in native ad spending in U.S. to come from mobile. Wall Street Journal.

Wojdynski, B. W. (2016). Native advertising: Engagement, deception, and implications for theory. In R. Brown, V.K. Jones & B.M. Wong (Eds.), The New Advertising: Branding, Content and Consumer Relationships in a Data-Driven Social Media Era (pp. 203-236). Praeger/ABC Clio.

Wojdynski, B. W., & Golan, G. J. (2016). Native Advertising and the Future of Mass Communication. American Behavioral Scientist, 60(12), 1403–1407.

Wojdynski, B., & Evans, N. (2016). Going Native: Effects of Disclosure Position and Language on the Recognition and Evaluation of Online Native Advertising. Journal of Advertising, 45(2), 157-168.

Wojdynski, B., Evans, N., & Hoy, M. (2018). Measuring Sponsorship Transparency in the Age of Native Advertising. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 52(1), 115-137.