Pocket-sized protection: how can personal safety apps affect surveillance in public spaces?

Walking home alone at night isn’t everyone’s favorite scenario. Especially (young) women run the risk of being assaulted when they are out by themselves during the evening or nighttime. Take for instance the case of Sarah Everard, who disappeared in London in March 2021 after leaving a friend’s house at night. Eventually, Everard was found to have been kidnapped and killed (Rawlinson, 2021). While anyone can experience the fear of assault during the darker hours of the day, it is especially common among women. According to Maxwell, Sanders, Skues, and Wise (2019), “women tend to experience higher levels of fear of violent crime than men, resulting in avoidant behavior, distrust of strangers, and anxiety.” Many public spaces contain some form of surveillance that could reduce the risk of violent crime, such as CCTV cameras. However, individuals themselves can also initiate other forms of surveillance through a wide variety of personal safety apps that are designed to make them feel safer by reducing their vulnerability to violence in public places (Maxwell et al., 2019). The question this article aims to answer is: how can personal safety apps affect the meaning of surveillance in public spaces?

A new layer of visibility

Personal safety apps introduce another layer of visibility to public spaces that is initiated by the user, rather than by the architecture of the public space itself. According to Jones (2017), public spaces are surveillant landscapes by nature because they enable visibility: they are “built environments that are designed to make people and their actions visible and legible”. Visibility can make people vulnerable depending on how power operates within a surveillant landscape, but it can also make them feel safe. In the latter case, visibility of and by others, for instance through lighting and CCTV cameras, can even be crucial in individuals’ feelings of safety (McCarthy, Caulfield & O’Mahony, 2016). This is perhaps why most personal safety apps are designed to help users contact someone they trust as soon as they feel at risk (Ranganathan, 2017). For example, the app bSafe lets users create their own ‘security network’ out of guardians they trust. The app contains several features that are designed to make users feel safe, such as GPS tracking, timer alarms, fake calls, and an SOS button. When the user activates the SOS button manually or through voice activation, their guardians get access to their location and can see and hear what is happening via live stream (as shown in Figure 1) (bSafe, n.d.).

Figure 1. The bSafe app’s live streaming feature

Such features can enable additional forms of surveillance. More importantly, they allow the users themselves to communicate the surveillant potential of public spaces, rather than surveillance communicated through solely the material and semiotic dimension of the surveillant landscape they are passing through. As a result, users’ mutual monitoring practices in public spaces are changed (Jones, 2017).

The control over surveillance

As personal safety apps introduce other ways of mutual monitoring, they can influence the power structures that operate in surveillant landscapes. Power in public spaces operates both through surveillance itself and through controlling who has the authority to surveil. Personal safety apps can affect surveillance in public spaces by destabilizing the control over whom has the authority to surveil (Jones, 2017), and therefore affect this operation of power because they allow users to take on the role of ‘the watcher’ looking out for ‘potential threats’. This also means that they can play a role in labeling the individuals that are present in public spaces, therefore influencing the relationship(s) between them.

Personal safety apps can affect surveillance in public spaces through destabilizing the control over whom has the authority to surveil

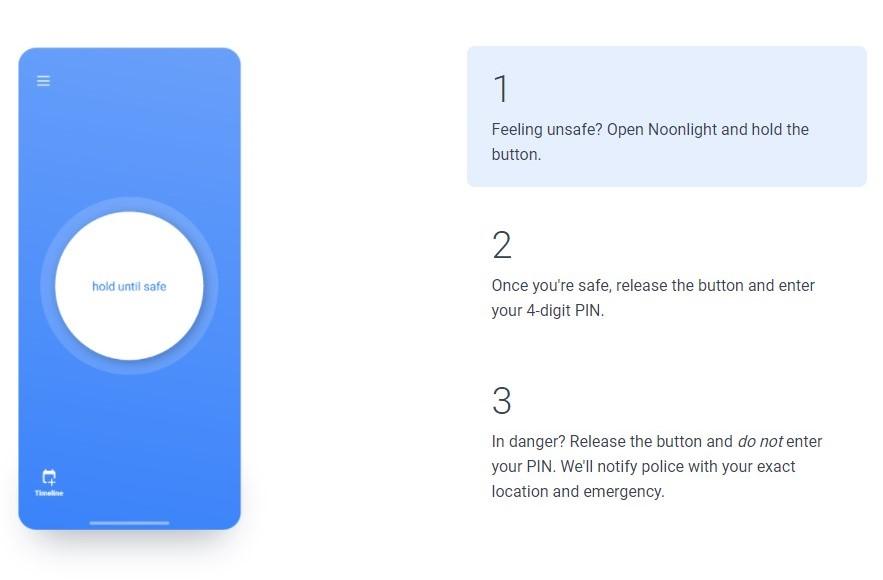

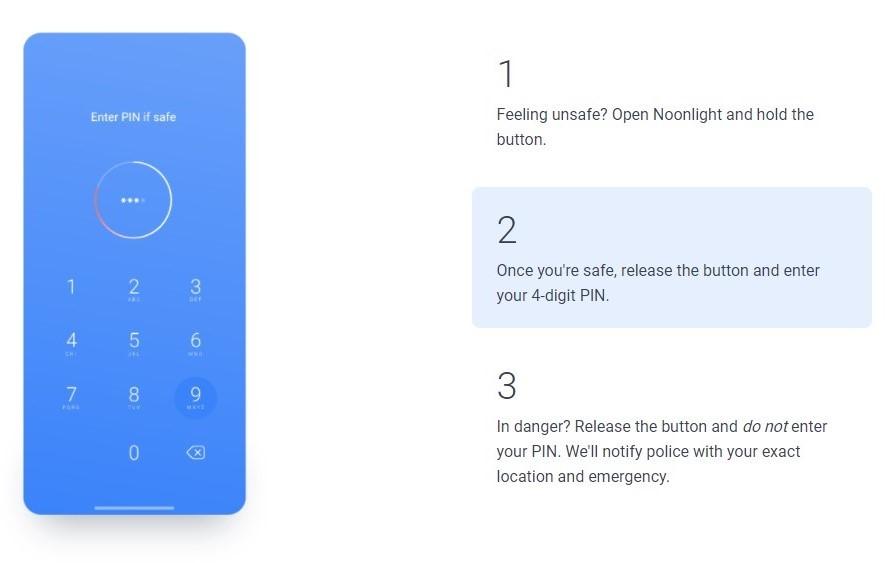

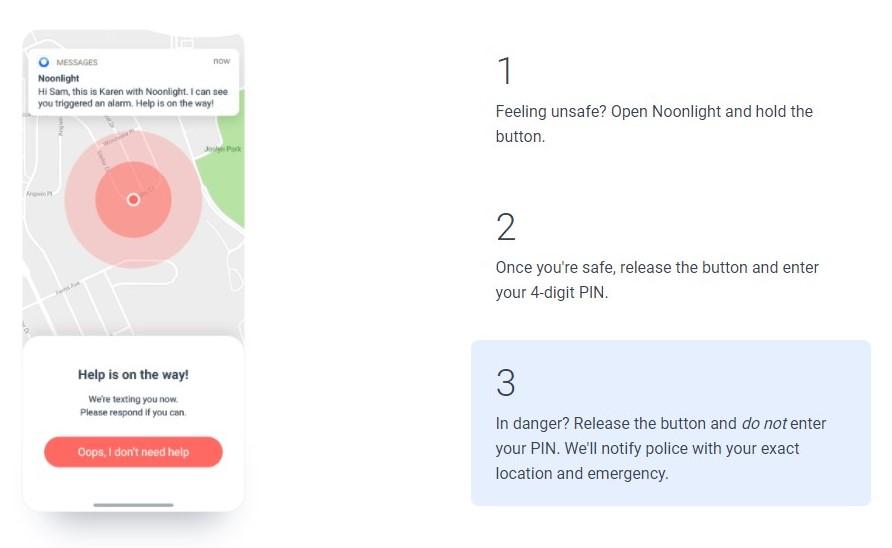

In other words, personal safety apps can change the interaction orders that are at work in surveillant landscapes. Interaction orders are, according to Jones (2017), “the kinds of ‘social situations that built environments help to make possible, including the possibilities for ‘mutual monitoring’ they make available, and the way they facilitate certain kinds of ‘performances’.” These interaction orders help to establish certain relationships between the watcher and the watched (Jones, 2017). For instance, police officers are often positioned as more powerful, or as promotors of safety in many public spaces. Sometimes this relationship is further reinforced by personal safety apps. Perhaps this is a logical choice, as McCarthy et al. (2016) found that a police monitoring feature in personal safety apps can have a positive impact on users’ sense of safety (McCarthy et al., 2016). The app Noonlight, for instance, notifies the police and sends them the user’s location if they don’t respond in time (as shown in Figures 2, 3, and 4) (Noonlight, n.d.).

Figure 2. The button in the Noonlight app

Figure 3. Users enter a 4-digit PIN in Noonlight once they’re safe

Figure 4. Noonlight notifies the police and sends the user’s location if they don’t respond in time

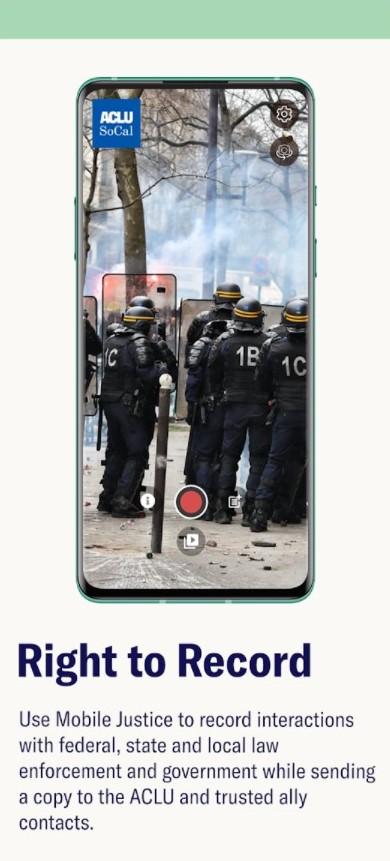

However, such features assume the privileged experience that authorities will always provide protection even though this is not the case for everyone. The worldwide protests against racism and police brutality after the killing of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor and Daunte Wright are just recent examples that show how the relationship between police officers and citizens is not always one of protection, but sometimes one of violence. Some personal safety apps take this in mind, affecting the interaction orders made possible by surveillant landscapes. One of them is the American app Mobile Justice, which lets users record interactions and/or incidents with authorities, and send these recordings to trusted contacts and their local American Civil Liberties Union (as shown in Figure 5) (ACLU, n.d.).

Figure 5. The Mobile Justice app

Empowering exhibitionism

Another way personal safety apps affect the meaning of surveillance in public spaces is through the empowering effect they can have on users – especially the ones that target women’s safety. The use of tracking or messaging features via mobile technology is one of the most common ways women attempt to gain some sort of control over their safety and protection in public spaces. Notably, because their freedom of movement in public (urban) spaces is restricted. Women don’t have the same level of access to, and spatial mobility within public areas as most men. The patriarchal gender system often forces them to avoid risks and not attract too much attention (García-Carpintero, de Diego-Cordero, Pavón-Benítez, and Tarriño-Concejero, 2020).

As women are both members of society and dwellers of surveillant landscapes, we see the combination of two power regimes that Koskela (2004) identifies as ‘the regime of control’ and ‘the regime of shame’. In the regime of control, power and visibility are used to regulate individuals in society, while the regime of shame is about individuals’ internalization of control. Koskela (2004) argues that individuals can refuse to participate in these regimes of power by deliberately producing and revealing images. As a result, they can feel liberated from the need to hide, something she describes as ‘empowering exhibitionism’. While Koskela (2004) uses this notion mainly in the context of revealing content that changes conventional codes of what can or cannot be shown, it might still be useful when looking at the use of personal safety apps. As a woman, revealing information through the tracking features of these apps can perhaps be seen as a form of empowering exhibitionism itself: as a way of resisting their unequal access to public spaces and therefore the patriarchal gender system.

As a woman, revealing information through the tracking features of these apps can perhaps be seen as a form of empowering exhibitionism itself

Important, however, is to not overlook the very reason why women use personal safety apps. The rejection of oppressive systems is likely not the main motivator, but rather the management of (internalized) fear when being out alone at night. The use of mobile technology can support agency from the user by giving them a sense of control over a surveillant landscape and by becoming the watcher. However, and as will be discussed later in this article, this agency can be questioned when looking at which information is shared through these apps and how. It also assumes a lot about whom this information is shared with; As Maxwell et al. (2019) point out, most personal safety apps targeted toward women’s safety do not consider the complexity of assault cases against women. As most of these apps are designed to help users contact others by sharing their whereabouts, the question rises if they really have such an empowering effect after all – especially since violence experienced by women is more likely to be committed by intimate partners or family members (Maxwell et al., 2019). Particularly in such cases, personal safety apps do not offer a waterproof strategy against assault. Additionally, the meaning of surveillance can be entirely different there: where visibility is empowering for some, it might make others even more vulnerable. Thus, the use of mobile technology may help women manage their fear of crime, but does it also reduce their vulnerability to victimization? (Maxwell, Sanders, Skues, and Wise, 2019).

Feeling safe = being safe?

So while mobile technologies can support active agency from the user’s perspective, they can also be used to repress them (Koskela, 2004), not only by whom the user gives access to their whereabouts but also by how their data is collected. Users of personal safety apps are participating in their own surveillance: they are required to make themselves visible – and thus subject to surveillance – if they want to use these apps to their full extent. This might be exactly the point to some users. For instance, McCarthy et al. (2016) studied the relationship between personal safety apps and perceived safety, privacy, and download preferences and found that participants were more likely to download a personal safety app if it contained a tracking feature, rather than a singular location feature (McCarthy et al., 2016).

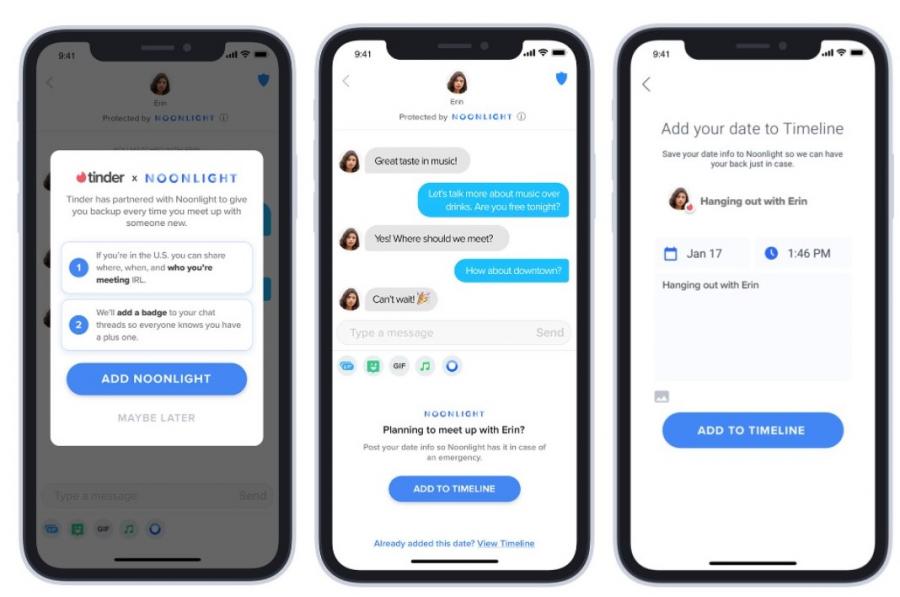

However, the use of personal safety apps does not happen without a trace. They can help create what Koskela (2004) calls ‘doubled digital individuals' out of its users. Personal safety apps generally position themselves as a tool for protection, but the state of privacy within such apps can be questionable. An analysis by Parachute found that 20 popular iOS safety apps send users’ information to data collection companies mostly without users’ knowledge and ability to control this (Parachute Engineering, 2020). The previously mentioned app Noonlight is a prominent example of this. Noonlight has several partners, including Facebook and YouTube, collecting some sort of information from their app. Apart from this, Noonlight also collaborates with the dating app Tinder by providing a safety feature that is meant to make Tinder users feel ‘protected’ while going out to meet someone new (as shown in Figure 6) (Tinder, n.d.). According to Warzel (2018), Tinder itself is also known for sharing user data with Facebook (Warzel, 2018). The data shared from personal safety apps are not only about device specifications and download statuses but can also concern very sensitive data in the case of actual assault (Wodinsky, 2020). Another unavoidable question of access and thus power arises: who has access to the data which is collected through the very apps that are supposed to be a tool for protection?

Personal safety apps generally position themselves as a tool for protection, but the state of privacy within such apps can be questionable

Figure 6. Tinder X Noonlight

Empowerment and vulnerability

Personal safety apps certainly play a role in affecting the meaning of surveillance in public, surveillant landscapes. They present a new form of visibility in such spaces that enable other ways of mutual monitoring for individuals passing through them. This can have consequences for the power structures and interaction orders that are at work in surveillant landscapes. Some personal safety apps can reestablish the relationship between individuals: a surveillant landscape can position certain figures such as police officers as more powerful, while some personal safety apps such as Mobile Justice can reposition them as possible threats.

While these apps can support active agency from their users, especially women who seek to gain some sort of control over their safety in public spaces, the question remains if they are providing safety or rather simply the feeling of safety. The design of most personal safety apps assumes that the user shares data with trusted contacts. However, especially for women, this is not always the case due to the complexity of assault cases involving intimate partners or family members. Whether the meaning of surveillance is about protection or increased vulnerability can therefore depend on the motive behind using these apps. In this sense, personal safety apps seem to disguise the meaning of surveillance in public spaces as empowering, while in reality, it might just make the user more vulnerable.

References

Clayman, S.E. (2001). Ethnomethodology: General. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioral Sciences (pp. 4865-4870). Elsevier.

García-Carpintero, M. Á., de Diego-Cordero, R., Pavón-Benítez, L., & Tarriño-Concejero, L. (2020). ‘Fear of walking home alone’: Urban spaces of fear in youth nightlife. European Journal of Women's Studies, 1350506820944424.

Goffman, E. (1964). The neglected situation. American Anthropologist, 66(6_PART2), 133-136.

Jones, R. H. (2017). Surveillant landscapes. Linguistic Landscape, 3(2), 149-186.

Koskela, H. (2004). Webcams, TV shows and mobile phones: Empowering exhibitionism. Surveillance & Society, 2(2/3).

Maxwell, L., Sanders, A., Skues, J., & Wise, L. (2020). A content analysis of personal safety apps: are they keeping us safe or making us more vulnerable?. Violence against women, 26(2), 233-248.

McCarthy, O. T., Caulfield, B., & O’Mahony, M. (2016). How transport users perceive personal safety apps. Transportation research part F: traffic psychology and behaviour, 43, 166-182.

Noonlight. (n.d.). How it works.

Rawlinson, K. (2021, April 16). Woman arrested in Sarah Everard case has bail extended. Guardian.