Lifesum Food Tracker: The Dynamic Environment of Self-Tracking

People’s desire to gain and exercise control over their lives is turning into a dominant practice with the emergence of all kinds of self-tracking apps that aim to improve individuals’ quality of life and provide them with a deeper understanding of their own habits. There has been a growing tendency for tracking productivity levels, sleep, eating habits, and even people’s spending hours online, leading to the release of more and more applications for self-monitoring.

The accessibility and usage of mobile apps for health and nutrition management are rapidly increasing. Their availability and user-friendliness turned the diet-tracking apps into an ally in their users’ efforts to maintain or lose weight. However, the long-term implications of such apps over people’s behaviors are complex. Thus, the aim of this paper is to explore the practices of food self-tracking and examine the nature of these technical devices beyond the purpose of their usage.

Is it really necessary to have a food tracker app?

It is challenging to determine exactly when food tracking began. However, the growing attention and increased usage are easy to grasp. The changes in the quality of food worldwide and the shift in people’s lifestyles had major consequences on the overall health of the population. The rates of obesity are increasing each year. Obesity among children and adolescents aged 5-19 has risen from just 4% in 1975 to just over 18% in 2016 (WHO, 2020). In 2019, the estimated number of children under the age of 5 that are obese is 38.5 million, and particularly in Africa, the percentage of overweight children has increased by almost 24% since 2000 (WHO, 2020).

The fast change in obesity rates was described as a health crisis by many dietitians and health organizations. However, obesity was not the only health issue that individuals should worry about. There is a major spread of diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and high blood pressure across the globe, particularly in America, with percentages increasing every year. As a result, a global concern from health institutions and professionals has emerged, as well as people's desire to preserve their health.

One connection between these health problems is food. “The number of people on specific diets to lose weight or to be healthier is on the rise, up nearly 22 percent from last year, from 14 percent to 36 percent, according to the Food & Health Survey released by the International Food Information Council Foundation” (Stych, 2018). Unfortunately, more and more people have reported the insufficiency of diets when it comes to the rate of success. “Around 80 percent of dieters regain all the weight they lost within a year, and 85 percent regain it within two years” (Norton,2020).

It did not take a long time for people to realize that dieting is not the answer to their health goals or problems. They needed something more than a restricting meal plan that had low-efficiency rates and was coming with a lot of demotivation. The major issue was the relationship that people had with food, as well as, their eating habits. Thus, food tracking devices and apps were offered as an answer to people's prayers and to help them gain insight into their own eating behaviors in order to establish control over their own health.

Users’ experiences with the Lifesum Food Tracker

Food tracking devices may be seen as a societal necessity to balance people’s food choices and help them achieve their weight goals, but these days apps are not always portrayed the same way as users experience them. The market of food tracking devices has become a competitive field with new apps being launched every month. Despite their different names, they mostly possess the same features such as customized accounts, calorie tracking, physical activity tracking, and water intake tracker. Thus, it is interesting to determine what makes some apps more desired by users than others.

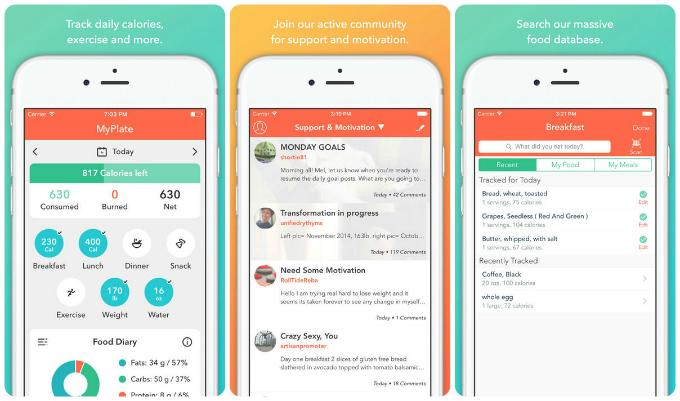

The diet and macro tracker ‘Lifesum’ has received a lot of attention in the last two years due to their strong marketing campaigns. The app has been awarded ‘Editor’s choice’ in the Apple store for 2018 and won ‘App of the Day’ in 2019. The tracking device has 45 million users who are “on the journey to better health and discover how tracking small habits can make a big difference in becoming happier and healthier” (Lifesum, 2021).

This health-transforming app offers its users the ability to get access to the basic features such as a customized account with calorie, physical, and water intake tracking for free, but it also has different subscriptions that provide users with the opportunity to receive a customized meal plan, have access to a food library full of recipes, detailed nutrition information, food ratings, etc. Furthermore, the app presents itself as a knowledge provider to empower users for a more conscious meal and grocery choice, helping them to determine which kind of food they should consume more and which less, and of course assisting with switching brands for better quality food.

The description of the app leaves the readers with no doubt that this app will solve all of their food consumption habits for the better. Just by downloading this single app, you could make your life happier and healthier. However, the way something is represented does not always equal reality, but is that the case of Lifesum?

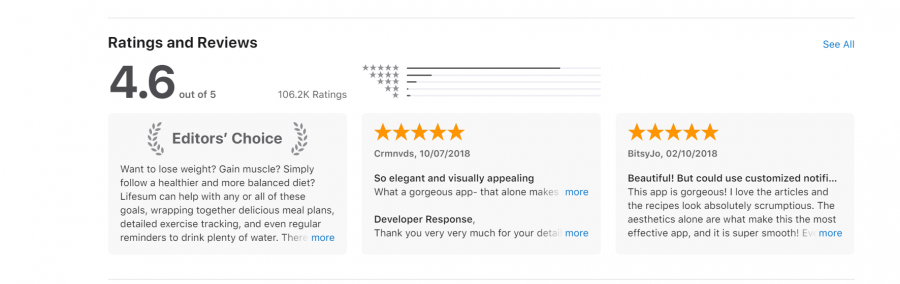

Figure 1: Lifesum rating in the Apple store.

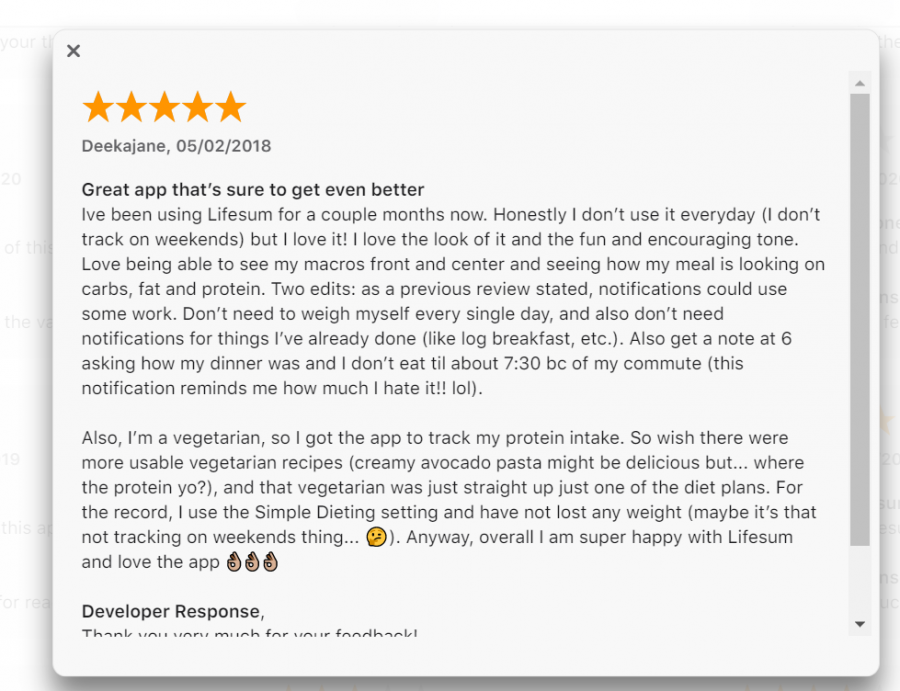

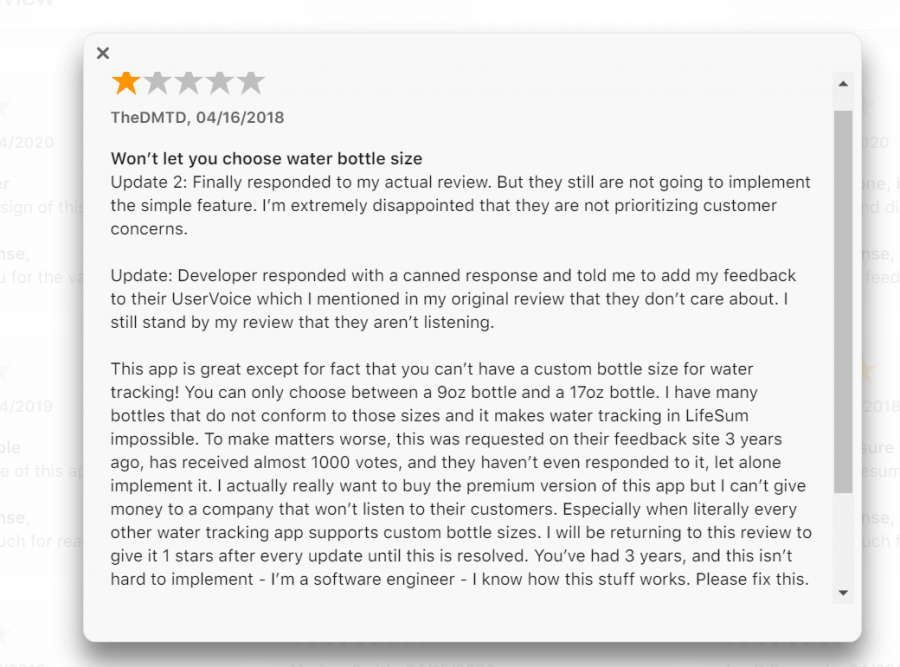

The app has 4.6 stars out of 5 in the Apple store (Figure 1). One user shares: “What a gorgeous app- that alone makes me want to open it and track. I love that it there's a water tracker, daily fruit and vegetable and weekly seafood tracker and that they give you a life score with details on what to improve each week” (Crmnvds, 2018). Most of the reviews are providing detailed descriptions of what users like the most in the app and what they consider as improvement needed (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Detailed review of a use about Lifesum.

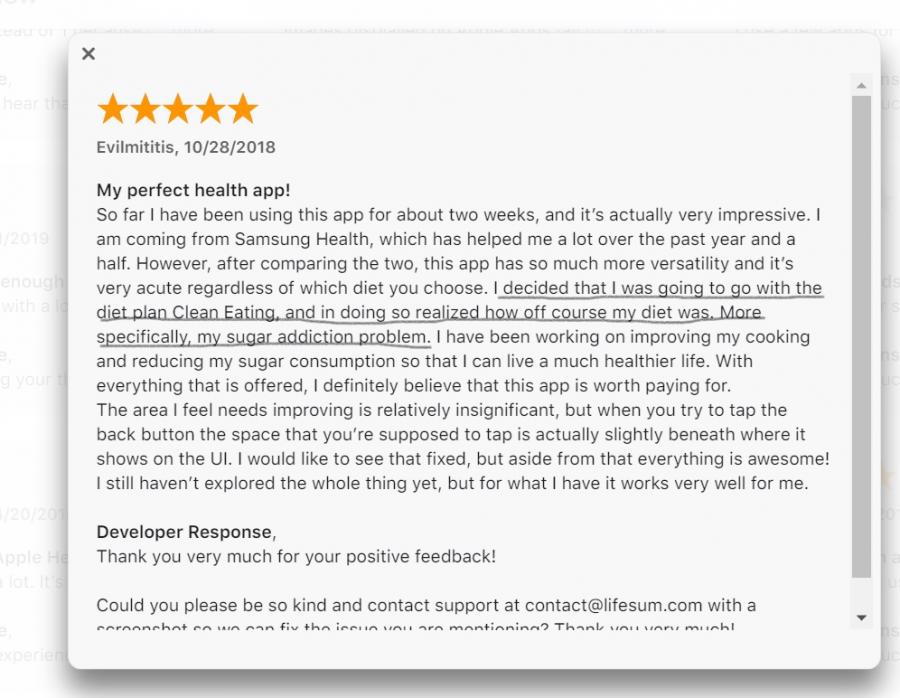

Other users even share not only their overall experiences with the app, but also, the ways the app changed their life (Figure 3). As we can see, for Evilmititis, Lifesum provided her with a diet that helped her to realize that she had a high sugar consumption that she needed to reduce.

Figure 3: The thoughts of a user of Lifesum.

However, not all experiences with Lifesum were this positive. Some app users had problems with the updates of the app that lead them to cancel their subscriptions: “The app is updated to the most recent version and so is the software on my phone. Have tried to resend the message several times and the app keeps crashing. I want to cancel my subscription and plan on deleting the app TODAY” (BaeNextDoor, 2019). Others find the customized features unsatisfying and quit the app straight away (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Lifesum user problems with customization.

Although there were negative opinions about the features of the app and the lack of update performance, the majority of reviews are on the positive spectrum, positing the app as promising for fulfilling the promises towards its users and justifying the rating that it has.

Private and pushed self-tracking: the fine lines between self-tracking

Individuals’ goals for downloading and actively participating in the usage of food tracker apps like Lifesum are various. Some do it with the desire to maintain or lose weight, to understand their eating habits deeper out of curiosity, while others do it to get meal plan ideas and recipes. However, looking beyond the surface of framing these apps as health improvers, their nature is apps for self-tracking, setting the beginning of a new behavioral practice - self-monitoring.

“Self-tracking at first glance appears to be a highly specialised subculture, confined to the chronically ill, obsessives, narcissists, or computer geeks. Many portrayals of self-tracking represent it as a voluntary and private practice, undertaken for purely personal reasons. This form of participatory self-surveillance is often represented as distinct from and in opposition to covert forms of surveillance or those that are imposed upon people” (Lupton, 2014). Self-trackers could collect data on one or two dimensions of their life for a short period of time or focus on hundreds of phenomenons for a longer period, but no matter which one these people chose, they collect information about themselves as a way to record specific aspects of their lives (Lupton, 2014).

A common practice of self-trackers is to analyze and interpret the data after its collection. However, whether the collected data is big or small, it is often positioned as an anonymous form of ‘big data’ sets that generate information regarding individuals’ interactions with social platforms and mobile devices (Lupton, 2014).

As a behavioral practice, there are different types of it - private, pushed, communal, imposed, and exploited self-tracking. In the case of food tracking apps, mostly this form of self-surveillance is private, meaning that the users are using the information collected with achieving self-awareness and improving or managing aspects such as sleeping, eating, work productivity, relationships, etc. Frequently, this initiative is voluntary as part of the journey of self-discovery and self-optimization and as a “playful mode of selfhood” (Lupton, 2014). However, pushed self-monitoring could easily be mistaken for being private since the lines between the two are being blurred, and due to celebrities' and influencers' promotion practices, they are getting even thinner.

The YouTube channel of Sanne Vloet is a perfect example of how private self-tracking could turn into pushed self-monitoring. Sanne is a famous model that has also been known as one of Victoria’s Secret angels whose body has been framed by the mainstream media and society as the so-called “body goal”. She began her YouTube channel where she shares all kinds of health and wellness videos. Her audience consists of young girls and women who are either her fans or people who are interested in how she achieved and maintained her weight. Sanne often published ‘What I Eat in a Day as a Model’ videos in which she often promotes Lifesum as an app that she uses on a daily basis (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A screenshot from ‘What I Eat in a Day’ video of Sanne Vloet.

Sanne is not a complete vegan but she tried to eat as a complete vegan once per week, thus “Lifesum has been extremely helpful” for her to track if she gets all of her nutrients (Vloet, 2019). She is definitely not promoting it as an app for losing weight or maintaining her weight but frames it as a health and wellness app that assists her in keeping track of her macros, and whether she is providing her body with all of the nutrients that it needs.

Her video was watched almost by one million people and taking into consideration her persona, the influence that she has over her viewers is substantial. Many of her viewers want to achieve Sanne's body shape, thus they are following her channel closely to view her diet, exercising plan, and any other tips she could provide. Therefore, she is able to completely change people's eating habits and food behavior by simply mentioning it in a video. Messages pushing such tracking on people abound on social media every day.

Therefore, pushed self-monitoring differs from “private self-tracking mode in that the initial incentive for engaging in self-tracking comes from another actor or agency. Self-monitoring may be taken up voluntarily, but in response to external encouragement or advocating rather than as a wholly self-generated and private initiative” (Lupton, 2014). Advocates for pushed self-monitoring are particular figures in the interest of self-care and health promotion. Arguments for persuading people to begin food tracking are gathering data in the context of encouraging self-reflection and health improvement (Lupton, 2014).

The dangerous side of self-tracking

It is highly neglected by individuals that self-tracking as a practice is an active form of data gathering with a specific purpose, however, it is still data collection, leading to the production of data assemblages. “ A data assemblage is a complex sociotechnical system composed of many actors whose central concern is the production of data” (Lupton, 2014). Thus, the data in data assemblages is organized by business and government models, human users, software, and sometimes even networks of other actors that are not the self-tracker who collects this data for personal purposes. The use and ownership of self-tracking data by agencies apart from the individual who has generated this data begin to have serious implications over social discrimination and justice (Lupton, 2014).

The algorithms that are bringing that data together result in creating ‘algorithmic identities’ that could have material form and could easily be used as a surveillance technology for exercising social disadvantages over marginalized groups. The issue arises because people are unaware of the extractions of this data, how it is being analyzed, and eventually employed. The production of data assemblages through self-tracking is a dynamic type of selfhood that is available for new interpretations causing exploitation in its new forms. The practice of self-tracking in its focus on individuals’ lives could be framed as contemporary biopolitical governance and economies resulting in the personal data collected from self-tracking to be a form of ‘lively capital’ (Lupton, 2014). The 'live capital' in itself is the data currency conveyed by people, which in our case is commodifying people’s lives and bodies.

Conclusion

Food tracking is turning into dominant practice by people for exercising control over their weight and overall health. The changes in the global food system, resulting in an increase of illness over the population, lead people to look for solutions, in which they are in control of their own health. Food tracking devices like Lifesum without a doubt are fulfilling that purpose, despite the inconvenience they may cause with the occurrence of technical issues. Nevertheless, more and more people are signing up for them and beginning their participation in self-tracking.

However, self-tracking is still a form of tracking, in which data sets are being used by third parties without individuals’ knowledge or consent. The data produced by self-tracking creates a coded version of ourselves that is revealing insights about our behavior, making the prediction of our own actions easy for other actors and agencies. Therefore, self-tracking could lead to self-improvement and self-optimization but the side effects over the participants' lives should not be passed by, since they can include discrimination, biases, and social injustice.

References:

Lifesum: Diet & Macro Tracker. App Store. (2021).

Lupton, D. (2014). Self-Tracking Modes: Reflexive Self-Monitoring and Data Practices. SSRN Electronic Journal.

Norton, L. (2020). Why Your Diet Isn't Living Up To The Hype. Bodybuilding.com.

Obesity and overweight. Who.int. (2021).

Stych, A. (2018). Percentage of dieters more than doubles. Bizjournals.com.