Afro hair, Afro beauty, Afro Italian

A journey through three micro-hegemonies that made up my personal identity

In this paper I intend to retrace how the process of identity construction and representation occurs as a result of the complex interplay between several micro-hegemonies (complex orders composed of different niches of ordered behavior and discourses about ordered behavior (Blommaert & Varis, 2015) and within today’s on and offline environments.

It’s all about the 'fros. A journey through the micro-hegemonies of hair beauty and nationality that made up my Afro-Black-Italian identity

Recalling my personal history I will focus on three particular micro-hegemonies that played a pivotal role in how I define myself: the ones of hair, beauty and nationality. In doing so I will illustrate how the identity process within today’s society is affected by both individuals’ and communities’ discourses.

The micro-hegemony of Afro hair

My hair has always been an important feature of how I define myself. It has always been a crucial part of my identity formation, also because of its uniqueness if compared with school mates and peers living in the same environment. I grew up in Italy during the 90s, a period in which the society was far less multicultural in contrast to other ex-colonist countries (i.e. United Kingdom, France and Germany). By then, the complexity and the range of mobility features employed to migrate were not yet amplified by the advent of the Internet and other aspects of superdiversity (Vertovec, 2007). For these reasons, I was not raised in an environment surrounded by people from diverse ethnic and cultural background.

At primary school I found myself being just one of the few pupils with non-Italian origins and just one out of two with African roots. The majority of children and people that I encountered was Italian and therefore I used to perceive them as belonging to the same ethnic group. To me they shared similar physical characteristics and hair types. No matter the differences between the color and texture of hair, I used to label them ‘Italian hair type”. Whether the hair was blonde, red or brown, straight, wavy or curly, it was all the same in my eyes. That simply meant "not Afro".

My hair was differing hugely from the people surrounding me. What I disliked the most about my hair, was not the texture itself, but rather the fact that it prevented me from conforming to my peers. It was forcing me to get attention without my intention. While striving to achieve conformity and be recognized as someone sharing Italian cultural values, I realized that conformity was both a social and cultural ideal (Blommaert & Varis, 2015). By then, I lacked the feeling of inclusiveness that I used to perceive as paramount in order to fully fit the community. I was feeling Italian like everyone else around me, but physical features such as my hair were giving my identity away and let people define what I was before I could even pronounce a word, even though my Milanese accent was a strong proof of my “Italianity”.

The confusion I was experiencing was absolute. I could not believe that trying to hide a natural feature common to the Afro ethnicity could be seen as a matter of “African” pride.

I spent my childhood wearing braids that my mother was patiently redoing every couple of weeks, a procedure that took us an entire Sunday. Unless my hair was "done" I would not dare to go out, not even for a tempting ice-cream offer. After the first years at school, people got accustomed to my look and I finally managed to answer satisfactorily to the silly and curious questions that were asked by young or even older people. The questions were something like if I was born with braids, why my hair didn't look flat when it was wet, or if I had to drink a lot of sparkling water in order to maintain its frizziness. However, I did not intend to show a different and unbraided side of me. That would have risen new arguments and a possible reconsideration of my identity for people surrounding me. I was finding out that the perception of my true self had to do more with the labels that people attached to me rather than with a personal emic discourse (Blommaert & Varis, 2015).

The magic tool, the relaxer

In my early teenage years I found out about the hair relaxers and I immediately started to straighten my Afro hair. I was enchanted by what those products were selling: the lifestyle they promoted rather than the actual tool. They finally offered me what I had always been looking for, a means to make me conform to the community of the Western type of hair. Finally, I could share the value of having straight hair resembling the tidy Western look, indexical of standardization and hence inclusiveness to the community. In a nutshell, the relaxing product was my medium to conform to the normativity of the group (Blommaert & Varis, 2015).

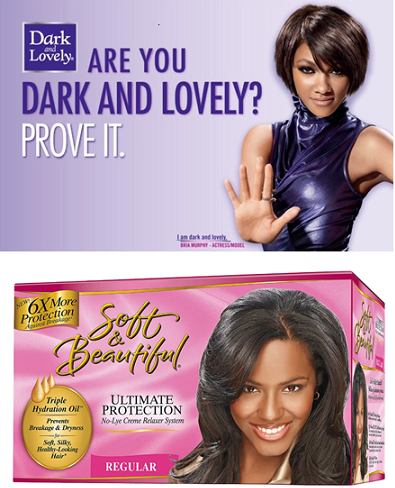

At the same time, those relaxing boxes, showing charming Afro-American women with long straight hair, were making me discover my belonging to a new community, the one of the Western and thus more emancipated (according to my by-then view) black women. The companies producing those hair relaxers used slogans and brand names like “Dark and Lovely”, “Soft & Beautiful”. They were implicitly, and at times explicitly, launching the message that every black woman with Afro hair should use them. This way they could achieve conformity to the Western world, where beauty ideals are associated with the straightness and softness of the hair. Moreover, the makeup, dress code and physical characteristics of the models advertising the products were constructed in such a way that every feature, except for the skin color, could recall Western women. Ultimately, in my view it was not possible to pursue or simply imagine another type of beauty. (See figures below)

My identity discourse, once my hair was conforming to and sharing the norms of both communities (the Italian one, and the one of the Westernized black women) started to become less problematic. My loyal imitation of hair relaxers’ testimonials made me perceive to have reached the enoughness of the emblematic features necessary to be recognizable as a member of those communities (Blommaert & Varis, 2015). I kept on relaxing my hair for a couple of years, being sure that I had found the proper way to represent my identity. I kept on with the relaxing routine until I came across a product that I had not seen before and that led me to question the overlap between Western and beauty standards. The new product was advertised through the same type of image, showcasing the beautiful testimonials with straight soft hair. My puzzlement stemmed from the name of the label itself: “African Pride”. The confusion I was experiencing was absolute. I could not believe that trying to hide a natural feature common to the Afro ethnicity could be seen as a matter of “African” pride. I started to realize how much "being beautiful" meant sticking to Western standards and hiding silently the majority of features recalling a different ethnicity (see figure below).

All the efforts I made to keep my image as close as possible to the expectations in my environment, had to be re-evaluated once I found out about hair weaves, in my late teenage years. Wearing weaves to create a long braided hair look was for me a sort of up-graded achievement of my true self, as I could wear a recognizable feature of my Afro origins without giving up a long mane. I felt that through braided extensions I could blend in at best with the Western representation of beauty (i.e. long hair) without giving up a more authentic Afro image.

What I did not expect, was a refusal from both sides of the communities in which I was desiring to partake. On the one hand, my Italian peers were admitting the final partial recognizable feature of length, but claiming that it was fake, thus unreal, whereas on the other hand, my new hair look was seen by a few of the Afro-Westernized women as a forced attempt to kill two birds with one stone. They thought that a braided look was accepted just for teenagers or for women during their leisure time, that is outside the context of the Western labor market, in which it would have been considered unacceptable as it is marked as an African ethnicity feature.

At the same time, surfing on various blogs on the Internet I came across discourses of some black women claiming the fakeness of a braided look whenever constructed through hair extension. According to them the real identity of a black woman in a Western country has to be showed through a natural look without the aid of neither chemical relaxers nor hair extensions. In that group, the language codes used to address black women with a different view were particularly tough and aimed at humiliating opposed perspectives. (see figure below)

Bitches be looking like this when they take that weave out

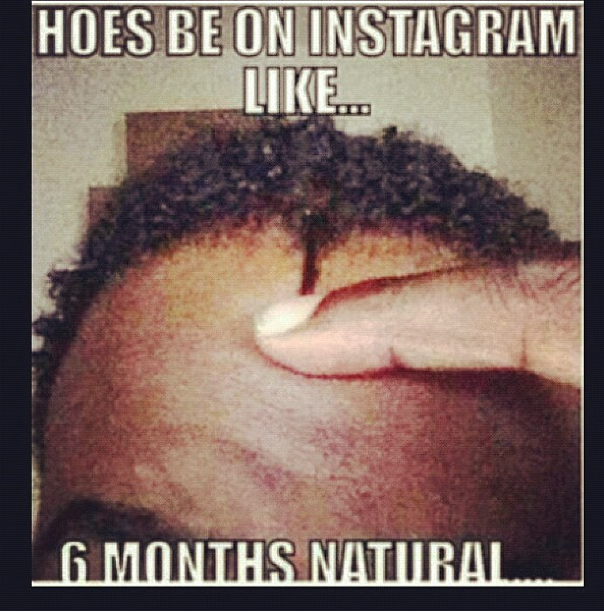

However, it was interesting to notice how these slurs and humiliating images were employed and considered allowed solely within the micro-hegemony (Blommaert & Varis, 2015) of black women's discussion on hair. In particular, these discussions were circulating within the niche of those supporting the natural hair(i.e. without relaxers or hair extensions) versus altered hair and therefore they were not perceived as racist or race-related. A similar language code is also employed and somehow accepted within the broader black community in which men make fun of the naturalistas [1] through several memes like the following one.

Hoes be on Instagram like…6 months natural…..

The willingness to give a representation of myself that could fit into a community and made me feel as showing my "true self", led me to decide for a big chop[2] and to simply wear my hair as it was naturally growing.Further, to avoid Afro hairdressers' discourses supporting chemically altered hairstyles and to overcome the anomie (Blommaert & Varis, Personal Communication, 10th September, 2015) I was experiencing, I developed a new rule: each time I wanted a short haircut similar to the ones of Afro males, I would join an Afro barbershop instead of an Afro hairdresser.

This decision created a great confusion among the Afro hair community I was joining and although my requests were the same as the ones of males customers, I was stigmatized as a deviate person because I was not conforming to the gender norm of the right place where to have a haircut. As a result I was put aside from the rest of the Afro hair community into the category of a probable "Afro-lesbians" instead of the broader one of an Afro girl wearing short natural hair. All this made me aware of the huge fractalites (Blommaert & Varis, Personal communication, 8th September 2015) implications in the construction of my identity. Tellingly, features that on one level made me recognizable (Blommaert & Varis, Personal communication, 8th September 2015) as an authentic Afro-girl, on the other level were perceived as a claim of gender belonging.

I developed a new rule: each time I wanted a short haircut similar to the ones of Afro males, I would join an Afro barbershop instead of an Afro hairdresser.

The next hairstyle I wore was a big kinky-Afro[3]. This decision came along with a major consciousness about diverse representations of beauty and a renewed feeling of authenticity that I could express again through my hair.

The attempt to find out a new identity reflecting the developing process I was experiencing in my early twenties, led me to looking for groups and communities of people sharing my doubts on how to give an authentic image of a proud Afro-Italian girl at best. My need to discuss the issue with a diversified audience was greatly facilitated by online social platforms . Thanks to various blogs, Facebook groups and YouTube channels, I took notice of the identity discourses of black girls and women living in other Western countries. I discovered that I was not alone in dealing with the construction of an authentic identity through the emblematic features of hairstyle and beauty. Surfing the Internet I came across numerous fascinating debates and memes (see figure below) that addressed my interest. Therefore all the arguments I was researching about shifted from the magazines I could find at the Afro hair saloon to the online parallel world.

Knowing who you are gives you power over those who challenge your identity

The majority of the discourses I was looking at were held by black girls and women sharing their perspective on how to showcase an authentic representation of the self, while being loyal to their own ethnic features. The fact that I was not looking at girls sharing their view from African countries was a consequence of the need of sharing perspectives with people living in Western countries who were experiencing an identity clash due to their different ethnic background. I needed to find a way to showcase my Afro-Western identity within the Western context.

The turning point: Afro-Italian Nappy Girls

The turning point within my identity process occurred through the discovery of the Afro-Italian Nappy Girls & Boys community. This group, which gathers its participants through the same Facebook name, is joined by and addressed to Afro-Italian girls and boys asking and sharing advices on the cure and maintenance of Afro hair as part of a broader identity-related discourse.

The common feature among people joining the community is the conscious decision to abandon chemical hair straighteners and to show off proudly their natural Afro texture. Significantly, wearing hairstyles that do not want to pursue or imitate the beauty ideals created by Western countries’ media is the dominant discourse of the group's founder, Evelyne Sarah Afaawua.

Evelyne is a young Italian woman with Ghanaian origins. She claims the right to call herself Afro-Italian, taking example from the Afro-American term. In her blog she explains the meaning of the word "nappy" which results from the blending of the adjectives natural and happy. "Nappy" entails that the choice of wearing natural hair is a conscious and cheerful decision. Furthermore, joining the community allowed me to acknowledge the fractality of the micro practices (introduced by Blommaert & Varis, 2015) shared by both Afro-Italians and other Afro-black communities. These communities all shared the idea represented by the figure below, which eventually went viral.

“Hey! Can I touch it?” “Bitch, I am not a sheep and this not a petting zoo. Stay the fuck away from me!”

Through the investigation of the micro-hegemony of hair, I was able to retrace the different niches I belong to. I started understanding the fractality of the practices and norms indispensable to perform, as well as the emblematic details (Blommaert & Varis, 2015) needed in order to fit and thus to be recognizable in a given community.

Afro beauty: micro-hegemony of beauty

Globalization and superdiversity have greatly impacted the understanding of beauty throughout the world. Thanks to the advent of the Internet and specifically thanks to social platforms like YouTube, today’s girls and women have the opportunity to discover the tools and to learn how to use them. This way they can reproduce a beauty image that reflects their unique style, while using the emblematic features necessary to fit and to be recognized as member of a given community.

MACcosmetics (MAC) is one of the world’s leading beauty companies producing professional makeup. Having worked for MAC as a makeup artist for several years, I experienced how the perception of beauty differs from person to person. One of the aspects that made the brand grow in popularity is the fact that the products are addressed to the widest type possible of clientele thanks to an attracting broad variety of colors for lipsticks and eyeshadows, but most importantly due to the broad choice of foundation shades covering almost every skin type.

Hence it can be said that the company’s marketing aims at addressing a superdiverse clientele. To support this, the motto of the brand, which states All ages, all races, all sexes, showing the company’s willingness to include the highest number of type and people, can be taken into account.

Another implicit message propagated throughout the makeup artists themselves, is to encourage clients to wear makeup according to their own personal style and to adapt it to the current fashion trends. This was a dare because you had to be unique and original, while still following up the fashion trends. To further reflect their superdiverse image, the company assigns to each shop a team of makeup artists that is usually composed of heterogeneous people in ethnicity, age and gender. Furthermore, the company’s policy invites its employees to showcase their individuality by not wearing a uniform.

The only requirement for the dresscode was that it had to be black. However, the makeup artists have to show their personal style by wearing catchy and fashionable clothes. And so the team of makeup artists would have been recognizable by customers for their superdiverse hair and beauty look, outfit and makeup worn.

Once I had overcome the identity crisis in relation to my hair, the company’s norms showed me the perfect context in which I could truly express my identity through the construction of my desired image. Indeed, my Afro hair was more than welcome and while working there, I was actually pushed by the supervisors to highlight my ethnicity features.

My vocational message was to tell black and black and Afro descendants people to be proud of their ethnic traits.

Finally, I could be my "true self" and I could help other people choose and produce the look that also reflects their own self . I found that the brand, with its products and normativity, was the perfect means that any woman and man could aspire to have. As a consequence, I decided to showcase at best the Afro beauty pride according to my view. I started to wear a foundation that was much darker than my actual skin color and to emphasize the prominence shape of my lips with bright colors. My message was to tell black and Afro descendants people to be proud of their ethic traits. This message was reinforced through the tools and moral support represented by the makeup artists. The brand’s intent then was supported by the heterogeneity of the testimonials employed by the launch of the new collections showing celebrities of a different race and gender posing together.

Little did I expect, this wide variety of foundations could also be a double-edged sword. A lot of “non-Western” customers were asking me for advices on how to portray Western standard about beauty rather than emphazising their own ethnic features. For example, many asked me for advice on how to portray foundation in lighter shades than their actual tone or contouring makeup techniques to minimize shape of lips and nose. Basically the majority was actually asking me to portray a standard of beauty detached from their ethnic features.

Skin color, one of the most characterizing feature of ethnicity was undoubtedly adapted to Western standards.

I felt to have failed in achieving my personal mission of spreading the pride of identity-related values through the representation of an authentic image. Therefore I started to investigate where, through which means and how such contrasting ideals were propagated. Quickly I found out that Internet as environment and YouTube as means formed the propagation instruments to teach methods to portray an image greatly detaching native traits.

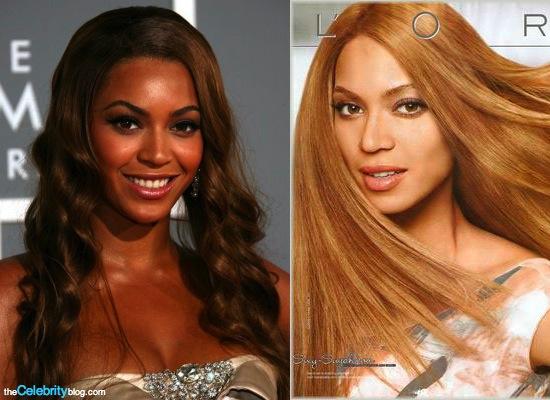

The micro-hegemony of beauty was then represented through uncountable niches encompassing different emblematic details to pursue(Blommaert & Varis, 2015). Among these niches the one composed by black women understanding fair skin as a feature of beauty, was supported by several advertisements of beauty brands . Those advertisements were on one side emphasizing the beauty of an ethnically diverse testimonial, whereas the beauty features portrayed were the Western ones completely detached from an authentic image (see figures below).

Rhianna2colors

Beyoncé as usually appears in public and next to it while modelling for L’Oréal, 2008.

Those images have raised great debate among makeup bloggers, vloggers and YouTubers[4]. Skin color, one of the most characterizing features of ethnicity, was undoubtedly adapted to Western standards.

Ultimately, confused by the variety of contrasting discourses I redefined my makeup practices by avoiding the use of a foundation as a claim of a truth, not disguised, but an authentic celebration of my skin color.

Nevertheless the representation of my identity through the image is still an interesting issue to me. Shifting from the chronotope (Blommaert, 2015) of a makeup artist in Milan (the city of fashion) to the one of a student in Tilburg (the city of the rotating house) my attention and concern about representing my true self through my image has drastically decreased.

Afro Italian: the micro-hegemony of nationality

Being born in Italy by Eritrean parents who raised me mainly according to the Italian culture , I always considered myself an Italian with Eritrean roots. Although at home the language allowed to be spoken was Tigrinya and the fact that the arguments were often related to Eritrea I did not feel any cultural difference compared to my Italian peers. I was sure about my Italian identity and had no doubts about pertaining the Italian thick community, to use a Durkheimian term. In spite of my feeling, some of the indigenous Italians I met did their best to question my identity discourse starting from the simple question: “Where are you from?” My answer was clear and loud and it was “From here!” Then, when repeating the same question as it was obvious that they expected an answer explaining my “non-autochthonous” image, I would have gone into details by saying that I was from Milano and further by stating the area in which I was living. This way, I was not trying to cease my origins but simply trying to “educate” my counterparts to ask the right question: “Where are you originally from?” Consequently, I would have told about my Eritrean roots and undergone the subsequent discourse about my “Italianity”. My strategy worked perfectly until I met some Habesha Ethiopian people claiming that I should consider my roots as Ethiopian rather than Eritrean as by the time I was born Eritrea was still under the Government of Addis Ababa. Indeed, Eritrea had been recognized as an independent country by the UN only in 1993 and as a matter of fact until then Eritreans were officially labelled as Ethiopians. This led me to rethink about the truthfulness of my origins, my perceived and actual national identity and their representations on my documents.

I always wondered which home I truly belonged to: Italy, Eritrea, Ethiopia or maybe the place where I was coming from according to my resident permit: the hospital.

My parents migrated to Italy during the 70s, during the civil war for the independence. Due to the Italian citizenship attribution criteria based on the ius sanguinis, I was not Italian according to my documents. On the other hand, due to the unstable situation of my parents’ country, I had no Eritreans papers either. Controversially, my documents were Ethiopian although I had never been there and in Italy I was considered as a regular immigrant with my resident permit stating as entrance date into the country, my date of birth. Consequently when facing racial discourses stating “Foreigners have to go back their homes” I always wondered which home I truly belonged to: Italy, Eritrea, Ethiopia or maybe the place where I was coming from according to my resident permit: the hospital.

In the long run, thanks to peers living the same experience, I have learnt how to share my Italianity feeling and my origins by defining myself as both an “Afro Italian” and a “black Italian”.

I thought that within this definition I could represent myself briefly and that I could be accepted by the Italian society who was needing to find out more about those “new Italians”. Unluckily the more I was involved in my Italian identity discourse, the more I found out that it was generally accepted only within informal environments. In fact, also the by-then Prime Minister Silvio Berlusconi revealed with his politics and behavior the low consideration of the “new Italians” discourses as well exemplified by his worldwide known statement about Obama’s historic victory in the 2008 elections: Obama is young, handsome and tanned (Glendinning, 2008) as to remark the incredulity of the US electorate in voting a president not pertaining to Western standards of physiognomy, among which the first one is whiteness.

Despite Berlusconi’s politics and behavior and thanks to the presence of a growing number of second generations, I felt that I could share my identity discourses in further niches besides the one of “the makeup artist” or the “Nappy hairstyles”. Therefore, I started to follow the real and virtual community of ReteG2 (NetworkG2). ReteG2 consists of young second generation people striving to achieve the recognition of their “Italianity” on a societal, institutional and political level. They demand gaining the right of citizenship for the underaged born or raised in Italy who have also been living there until reaching the legal age of 18th.

"Not only am I perfect, I'm Italian too" (Balotelli's t-shirt)

Within this community, which shares the emblematic feature of having a non-Italian origin, I started to broaden the context of my identity discourse to diverse spheres. For instance, I have become more keen on watching football, whenever the national team is playing, since the entrance of the “new Italian” player Mario Balotelli. Besides activism, sports have also played a role in spreading Italian identity discourses. Consequently, step-by-step “new Italians” are becoming more and more considered as proven by the recent achievement of ReteG2, being the revision of the citizenship law entailing less strict requirements to get the citizenship for second generations in October 2015. In line with the slowness that characterizes the Italian bureaucratic machine, parliamentary discussions are stuck and thus nothing is yet implemented. Although bureaucratic problems are slowing things down, progress is still being made and peopleare optimistic about it.

Mario Balotelli silencing racist chants after having scored a goal. AC Milan- Cagliari 10/02/2013 - Mario Balotelli showing his “Italianity” with a t-shirt stating” Not only am I perfect, I’m Italian too”

Who is Addes?

In this paper I recalled my personal experiences envisioned over three main different micro-hegemonies. Furthermore, I attempted to show how identity is not a fixed concept but rather a constantly developing one. I also illustrated how identity discourse vary throughout the chronotopes of Addes, first as a pupil, teenager, makeup artist and finally a university student. In so doing, I retraced how the representation of the self is not only an outcome deriving from the membership to a given thick community. Rather it entails the construction of a unique self that has to deal with the conformity to the rules of the light communities and to which norms we have to abide in order to be considered and recognized as part of it.

Notes

[1] A naturalista is someone who wears their hair the way that it naturally grows out of their scalp.

[2] A big chop is a drastic haircut in order to remove chemical treatment and obtain a natural state of the hair.

[3] A kinky Afro is thick, curly hair, which when taken out of braids resembles the Afro, which is common in people of African descent.

[4]See more on Hollywood Life

References

Alvesson, M., Lee Ashcraft, K., & Thomas, R. (2008). Identity matters: Reflections on the construction of identity scholarship in organization studies.Organization, 15(1), 5-28.

Blommaert, J. (2015). Chronotopes, scales and complexity in the study of language in society. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 121.

Blommaert, J., & Varis, P. (2015). Enoughness, accent and light communities: Essays on contemporary identities. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, 139.

Glendinning, L. (2008, 6 november). "Obama is young, handsome and tanned, says Silvio Berlusconi". The Guardian.

Jetten, J., Postmes, T., & McAuliffe, B. J. (2002). ‘We're all individuals’: group norms of individualism and collectivism, levels of identification and identity threat. European Journal of Social Psychology, 32(2), 189-207.

Vertovec, S. (2007). Super-diversity and its implications. Ethnic and racial studies, 30(6), 1024-1054.