The debate around Shelter

What the anime fandom constitutes as anime and what not

In this paper I use the debate around the music video Shelter to investigate how the term anime is culturally defined and if there is a difference in how people who are part of the anime fandom classify anime as opposed to people who aren’t. With the answers I gain from answering these questions I hope to give an argument as to why Shelter’s release caused such an uproar in the anime fandom.

Shelter?

October 18, 2016 a six-minute-long animated music video was uploaded to the YouTube channel of American DJ and musician Porter Robinson. The video was produced to accompany the single Shelter, a product of a collaboration between Robinson and French DJ Madeon.

The music video features the story of Rin, a 17-year-old girl who lives by herself inside a futuristic simulation, and was created in collaboration with Japanese animation studio A-1 Pictures and streaming service Crunchyroll. At this moment the video has over 9 million views on YouTube but within 24 hours of the video’s release it appeared on the front page of Reddit’s 430.000-strong anime subreddit only to be taken down by its moderators. The ban resulted in a heated discussion in the anime fan base, leaving the community with polarized views on what constitutes as anime and what not.

Meaning of the word anime

The online dictionary Merriam-Webster defines anime as “a style of animation originating in Japan that is characterized by stark colorful graphics depicting vibrant characters in action-filled plots often with fantastic or futuristic themes.” The word anime is abbreviated from animēshon the Japanese pronunciation of its English counterpart: animation. But whereas the term anime in Japan is very extensive and used to refer to all forms of animation, when the term is used in a Western context it refers strictly to animation originating from Japan.

Anime as a mass medium

One of the reasons why the meaning of the word anime in Western contexts is more specific and framed can be due to the fact that anime fandom in the United States and Europe exists as a subculture, whereas in Japan anime is a mass medium part of popular culture. Within Japan’s mediascape (Appadurai, 1990) anime ranges from films, television and even commercials and advertising, and it is accessible on a broad variety of platforms.

The popularity of anime makes itself physically apparent not only in various forms of merchandise, but also in the landscape as promotional pieces, anime-themed cafés or as tourist attractions such as the Ghibli museum, a museum showcasing the work of internationally successful animation studio Studio Ghibli.

In 2013 the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs Cool Japan Initiative was funded by the Japanese government, which aims to actively promote and support modern Japanese culture on a global scale and make the country’s culture industry a driving force in its economic growth (Fukase, 2013). An example is the handover presentation during the closing of the 2016 Rio Paralympics. The presentation promoting the 2020 Tokyo Olympics featured several cultural icons ranging from protagonists of popular anime titles such as Doraemon and Captain Tsubasa, to video game characters as Mario and Pac-Man (see Figure 1). The presentation ended with Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe taking the stage dressed up as the famous Nintendo mascot, Mario (Al Jazeera Turk, 2016). Promotions like these and the Cool Japan initiative help building global interest in Japan and the export of Japanese cultural products, branding commodities as anime as essentially and fundamentally Japanese.

Figure 1: Screen capture of Tokyo Olympics promotional video featuring Pac-Man (Al Jazeera Turk, 2016)

Anime in the West

It is only recently that Japan’s products of homegrown pop culture are increasingly being promoted as a transnational product with defined ties to its place of origin. However, that does not mean anime formerly had no presence in the American mediascape. Osamu Tezuka, internationally regarded as the “godfather of anime” defined what we know as anime today with his manga-turned-anime Tetsuwan Atom or Astro Boy (1963), as it was known in the United States. After being licensed by NBC enterprises (now known as Universal Television) the English-language version Astro Boy aired on American television for 12 years. Another influential work credited for increasing the popularity of anime outside Japan is Katsuhiro Otomo’s dystopian science fiction film Akira (1988) which after being rejected by Spielberg as “unmarketable in the U.S.” got a small theatrical release and garnered a huge cult following.

Localization

Some of the most successful stories in the localization of anime are Yu-Gi-Oh and Pokémon. Much like Astro Boy and Akira both were already proven, successful products domestically before being licensed by American publishers. In the process of adapting these products for Western markets and increasing their global appeal through translation, editing, dubbing and devising and manipulating content, much of the products' origin became obscured. Cultural practices represented in anime that did not translate over to Western viewers, were being altered or removed (see Figure 2). When these shows appeared on American television, they were often so heavily edited viewers had no real awareness that the shows were a Japanese product (González, 2006). While shows like Pokémon or Astro Boy are still prominently different from mainstream American productions, it is undone of its “Japaneseness", leaving mainly the aesthetic, the visual style as the indicator that is an anime product.

Figure 2: A comparison between a Japanese episode of Pokémon and the localized version by 4Kids (Cooper, 2016)

Censorship

The localization of anime also suffered heavily under censorship pressured by groups like ACT (Action for Children’s television) who’s censoring was not limited to cartoon violence but also content containing notions of homoeroticism, gender ambiguity, topics like death or anything that suggested the protagonist was not one hundred percent ‘good-guy’ material (Ladd & Deneroff, 2009). For example, one Astro Boy episode never aired in America because it showed animal experimentation and was deemed inappropriate for the intended audience. Censorship was also conducted in anime films targeted at adults, this mostly concerned specific themes e.g. the obscuring of drug references in the English adaptation of Akira.

Lower the barrier

An argument for this undoing of “Japaneseness” in anime can be found in an interview with translator Matt Alt, where he argues that in order for an anime to keep its entertainment value it is necessary to put a product through this heavy localization process in order to reduce the barriers for the target audience. The primary audience to which anime is marketed in the United States is children, which falls in line with the traditions of the traditional American animation industry, which unlike the Japanese animation industry, was originally not a multi-genre enterprise. This has led to the understanding that anime, and animation is generally regarded as something for children, like Astro Boy, or perhaps the case of animation for adult audiences like Akira, an occasional art-house film or minor art (Napier, 2007).

Fansubs and global distribution

Whereas anime was incredibly difficult to come by in the 1970s and 1980s, the development of digital media technologies propelled anime fandom into enormous growth. Where the early fans had access to anime through TV broadcasts and dubbed, imported or bootlegged videotapes (Plunkett, 2016), the anime fandom in the mid-2000s quickly expanded due to availability of fansubs: fan-made English subtitles distributed by unpaid, self-organized groups. Driven by love for the medium, the anime fandom took on this participatory role and started contributing to the bottom-up spread of anime as a cultural commodity across geographical and linguistic borders. The spread of English fansubs resulted in further distribution by other fansub groups in other languages e.g. German, Portuguese and Hebrew.

It was through fansub distribution that the anime fandom gained access to products of Japanese animation that weren’t box office breaking records like Akira or popular shows which were being marketed towards children in the like Pokémon. Fansub groups filled a gap in the market which was not filled by the current model of distribution of the Western cultural industries.

Fansub groups not only filled the role of translators and distributors, but also took up the role of mediators. Western anime fans became aware of the extent to which anime had been altered by localization and were disappointed by the degree in which the product was “Americanized” (Napier, 2007). With this awareness came a desire for a more “authentic” view of Japanese animation (González, 2006). In their pursuit of “authentically” experiencing anime and Japanese culture, fansub groups developed their own style of integrating these foreign cultural commodities into Western cultural context.

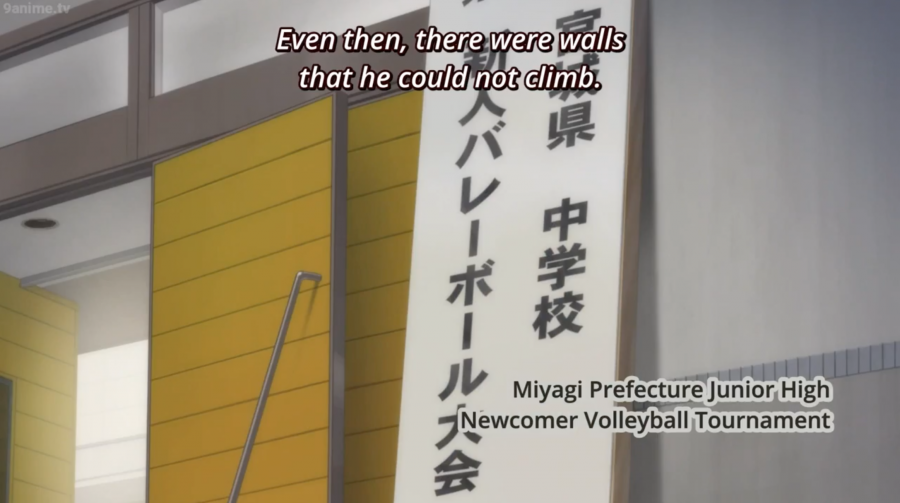

In order to get as much information across to the viewer it is not uncommon to see fansub groups take decisions that, when compared to official subtitles, seem more artistically intrusive. Figure 3 illustrates the inclusion of translation of text visible in the shot, which leads to the translation of the spoken lines to be moved to the upside of the screen for the sake of clarity. The displaying of honorifics, a fundamental part of sociolinguistics in the Japanese language, is also common.

Figure 3: Screen capture from Haikyuu!! (2015) fansub by Horriblesubs

Although fansubbing differentiates itself from copying and sharing e.g. ripping DVD’s released by official licencing companies, fansubs aren’t user-generated content either, as their existence depends on copyright protected cultural products. As such fansubbing has technically always been an illegal activity. Most fansub groups generally do abide certain ethical standards surrounding their distribution e.g. stop uploading shows that have been licensed in the respective region the fansub group operates. Not doing so might result in a backlash from their own community or in a very rare case result in the undertaking of legal action against a fansub group (Anime News Network, 2003).

While the fan base exceeded the Western animation industries in the cultural globalization of anime in terms of velocity and availability, legal distribution started to take off when streaming service Crunchyroll secured distribution agreements with Japanese companies in 2009. While Crunchyroll started out as an illegal fansubs community with fan-uploaded bootlegs, from 2009 and onward Crunchyroll strictly hosts content to which they have legitimate distribution rights (Anime News Network, 2008). Some argued that the emergence and success of streaming services such as Crunchyroll would ultimately lead to the “death of fansubs”, as it embodies many of the qualities that turned fans to fansubs instead of legitimate distribution channels: an “authentically” subtitled, digitally accessible product that is distributed with a velocity that allows shows to be viewed in mere hours apart from its initial broadcast in Japan.

The status of Shelter

The debate surrounding the status of Shelter seems to revolve around how anime is culturally defined in opposition to animation in the current Western mediascape. I argue that due to exposure to localized anime, which is undone of all its cultural references, those who do not venture deep into the anime fandom generally define anime by its visual style. This argument is also represented in online dictionary Merriam-Webster’s definition, who defines anime as “a style of animation originating in Japan”. Following this definition, some argue that Nickelodeon’s production Avatar: The Last Airbender is an anime. Regardless of its anime-like aesthetics and influences, it still remains a purely American production and as such, it technically is an anime-inspired cartoon. Some insight in what the anime fandom constitutes as anime can be gained from the guidelines of online anime database and community MyAnimeList, who define anime as follows:

“Professionally produced, animated works created in Japan for the Japanese market; in Korea/China for the Korean/Chinese market; as a joint production between Japan/Korea/China and another country.”

On the definition of what they don’t define as anime, and thus is denied entry in their database, the following can be found:

“Shows where all work, aside from the animation, was done outside of Japan/Korea/China (e.g. directing, script, etc.). For example, if a U.S. company outsources only the animation of a particular work to Japan, it will not be included in our database.” (MyAnimeList, 2009)

As Robinson was closely collaborating on Shelter’s creation with A-1 Pictures in Japan (Crunchyroll, 2016), Shelter is essentially a joint production, and thus an anime according to MyAnimeList’s guidelines. However, the Reddit moderators did not condone and posted the following explanation:

“The specific definition we use to determine "anime" is "an animated title, produced and aired in Japan, intended for a Japanese audience". This is a music video by an artist that contracted a studio that happens to also produce anime. If A-1 Pictures was contracted to produce episodes of SpongeBob, we wouldn’t allow that [on the anime subreddit] either.” (DrNyanpasu, 2016)

While both statements indicate that a Japanese animation studio being part of the production is a certain “necessity”, there is uncertainty if a production is still considered anime when a non-Japanese party enters this process. In the case of Shelter, I argue, the opinions within the fan base are very much divided depending on the person’s tolerance for “foreign interference” in a product that they want to experience as “authentically Japanese”. Along with the decision to premiere Shelter in Japan (Johnston, 2016), I argue that certain choices A-1 Pictures and Robinson made during the production steer in the opposite direction of what Western fans are used from anime targeting Western audiences. While the visual style is certainly very identifiable as anime which can be expected from a renowned studio as A-1 Pictures, the spoken lines are not in English but Japanese and the character names are chosen in Japanese tradition.

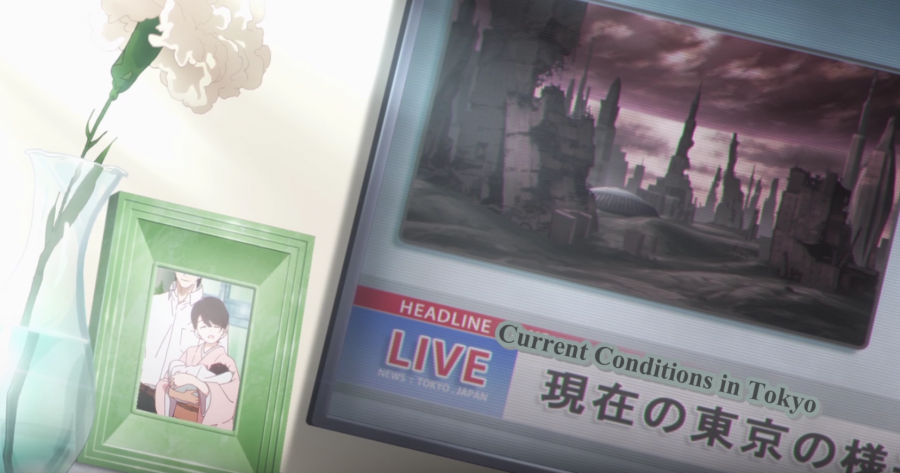

The Japanese language is also left intact when on screen e.g. on the interface of Rin’s tablet or the television. But also important to note is that the cultural references to its “Japaneseness” come in obvious forms like Rin’s temple visit in traditional clothing, to the shot where the character is seen carrying a red randoseru, a hard-sided leather backpack used by Japanese elementary schoolchildren, the traditional colors being black for boys, and red for girls (Gordenker, 2012). Although the shot is still understandable because it is recognizable as a backpack, at the same time viewers with a deeper understanding of these cultural references can identify it explicitly as a randoseru. Also anime never had a tradition of shunning themes that were deemed too controversial for animation, as noted earlier in this paper. I argue that the presence of themes like death and loneliness that are depicted in Shelter feed into the already large quantity of practices anime fans know from exposure to authentic anime (Napier, 2001).

Figure 4: Screen capture from Shelter (2016)

These choices convey a certain impression that it could be a product targeted at the Japanese market. Figure 4 illustrates a screen capture from Shelter with subtitles provided by Crunchyroll that stylistically are very reminiscent of the style of subtitling used by fansub groups in Figure 3. These factors taken together leads to the conclusion that Shelter can be experienced a product that aims to be very close to the “authentic”, “non-localized” experience that anime fans have sought for through fansubs.

References

Al Jazeera Turk (2016, August 22). Tokyo 2020’ye hazır [Video]

Anime News Network. (2003, June 8). A New Ethical Code for Digital Fansubbing.

Anime News Network. (2008, November 17). TV Tokyo to Stream Naruto via Crunchyroll Worldwide (update 2).

Appadurai, A. (1990). Disjuncture and difference in the global cultural economy. Public Culture, 2(2), 1–24. doi:10.1215/08992363-2-2-1

Cooper, T. (2016, March 8). 5 weird ways Pokémon has been censored.

Crunchyroll (2016, October 20). Porter Robinson’s SHELTER: Behind the scenes with Crunchyroll [Video]

DrNyanpasu. (2016, October 18). Porter Robinsons “Shelter” animated music video is out! It is amazing [Reddit comment]

Fukase, A. (2013, November 20). Tokyo launches “cool Japan” investment fund.

González, L. P. (2007). FANSUBBING ANIME: INSIGHTS INTO THE “BUTTERFLY EFFECT” OF GLOBALISATION ON AUDIOVISUAL TRANSLATION. Perspectives, 14(4), 260–277. doi:10.1080/09076760708669043

Gordenker, A. (2012, March 20). Randoseru.

Johnston, L. (2016, October 30). Porter Robinson seeks ’shelter’ inside a fantasy world for his anime debut.

Ladd, F., & Deneroff, H. (2009). “Astro boy” and Anime come to the Americas: An insider’s view of the birth of a pop culture phenomenon. Jefferson: McFarland Publishing.

Macdonald, C. (2003, June 8). Unethical Fansubbers.

MyAnimeList. (2009, December 6). Anime DB guidelines.

Napier, S. J. (2001). Anime from Akira to Princess Mononoke: Experiencing contemporary Japanese animation. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Napier, S. J. (2008). From impressionism to anime: Japan as fantasy and fan cult in the mind of the west. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Plunkett, L. (2016, November 22). Early Anime fans were tough pioneers.