Play and metapolitics in Angry Goy II

The release of alt-right indie game Angry Goy II did not go unnoticed – the videogame immediately sparked controversy due to its depiction of white supremacist sentiments and acts of violence against minority groups and was quickly banned on platforms like Steam and YouTube. Using Ian Bogost’s (2007) concept of procedural rhetorics to analyse how video games communicate political arguments and carry ideological bias, this paper examines how indie games like Angry Goy II use procedural rhetorics to construct the game’s messages, and aims to provide insights in how Angry Goy II functions as a metapolitical tool.

Politics, games and procedural rhetorics

Arguably there are many aspects that define the nature and working of digital games – they are highly interactive and communicative potential is multiplex, so how is meaning in games constructed?

In his book Half-Real (2005), Jesper Juul examines the interplay of rules and fiction. The “rules” constitute the ludic aspect – this dimension comprises elements of game mechanics, gameplay and game design: arguably the defining feature of games both digital and non-digital. The “fiction” refers to aspects of narration, this dimension comprises storytelling and design of characters, world and other thematic elements. The confluence of rules and fiction in Juul’s model ultimately make up the meaning-making process.

In the book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video Games (2007) Ian Bogost examines how video games persuade by virtue of their unique qualities and introduces the concept of “procedural rhetorics” – arguing that the computational, algorithmic affordances of video games allow for representations based on rules and interactions – as such they have the ability to create simulations of both real and imagined systems and their functioning.

Video games thus persuade by virtue of the player’s interaction with those systems and allow them to explore and form judgements about them. However, a game’s rules can enforce a particular perspective, and through procedural rhetoric video games can carry ideological bias, challenging or support existing societal positions.

Angry Goy II

Imagine a game in which you are sent on an important mission to rescue the president of the United States. This premise is hardly original in pop culture – from Escape From New York (1981) to games such as Call of Duty: Advanced Warfare (2014) and Metal Gear Solid 2: Sons of Liberty (2001), securing the safety of the nation’s leader is hardly an ingenious narrative.

This time, however, the player needs to fight their way through journalists, racial minorities, socialists, Jews and homosexual men in order to save president Donald Trump, who has been kidnapped by left-wing terrorists. This is the premise of Angry Goy II – a game promoted on the website of Christopher Cantwell’s Radical Agenda podcast as “…the season’s hit game for White males who have had it with Jewish bullshit” where “instead of taking out your frustrations on actual human beings, you can fight the mongrels and degenerates on your computer!”

The title of the game refers to the word goy, a term in Hebrew and Yiddish to refer to a non-Jewish person, now part of white nationalists'antisemitic discourse.

Angry Goy II is the sequel to Angry Goy, developed by the relatively unknown Wheelmaker Studios, which was released as an indie freeware game in 2017. The title of the game refers to the word goy, a term in modern Hebrew and Yiddish to refer to a gentile or a non-Jewish person. However, due to discursive appropriation, the term was incorporated in white nationalist’s antisemitic discourse.

Now the term is used in different manners: from use in the catchphrase “The Goyim Know” – a pseudo-Yiddish phrase used to impersonate and mock Jews and perpetuate antisemitic conspiracy theories, to the name of the alt-right fundraising website GoyFundMe (a play on the popular GoFundMe platform), which is used to fund Nazism. As such the term can be deemed empowering to white supremacists.

The release of Angry Goy II was met with scepticism – the game is mainly compromised of 2D sprites, low-resolution video files, and takes approximately not more than an hour to complete, despite its 700 MB file size. The suspicion was raised that the size of the file was possibly due to the inclusion of malicious software like a keylogger, and that the game was released as a 'honeypot' by the FBI.

Regarding these concerns, Cantwell expressed that “…people in our circles would want to avoid being infected with such a problematic piece of malware even more than the average citizen.”, and stated the large game file was due to the relative incompetence of the developers. The promotional teaser of Angry Goy II and all videos containing its gameplay have been banned from YouTube on grounds of violation of its hate speech policy.

A spokesperson for the charity Community Security Trust argued that the game might seem like a “…pathetic example of race hate”, but speaks to a “…deep incitement to commit murders inside gay clubs and synagogues,” familiarized to us by mass shootings at such locations – which makes the game “…dangerous and stomach-turning” (Palmer, 2018).

Introducing the right wing death squad

The gameplay of Angry Goy II heavily borrows from the top-down shooter (or shoot-em-up) genre popularized in 80s arcades – which due to resurging interest in retro games inspired games like Hotline Miami (2012) in recent years. The technological limitations of early computing systems are manifested in linear yet rudimentary gameplay – the player has to eradicate all enemies present in a level with the weapons available to his or her avatar. Only if this requirement is met (all enemies are defeated, and the player’s avatar is alive) an elevator will open, thus allowing the player to advance through the game.

Angry Goy II features retro visuals paired with an electronic soundtrack which aligns with the popular alt-right aesthetics of fashwave – the aesthetic adopted by the movement which mimics synthwave’s retrofuturism combined with the addition of white-nationalists themes and Nazi imagery. Andrew Anglin, founder of the Daily Stormer, describes the genre as the soundtrack of the alt-right – free of African rhythmic influence and thus praising it as the “whitest music ever” which is “the spirit of the childhoods of millennials” and “the sound of our revolution".

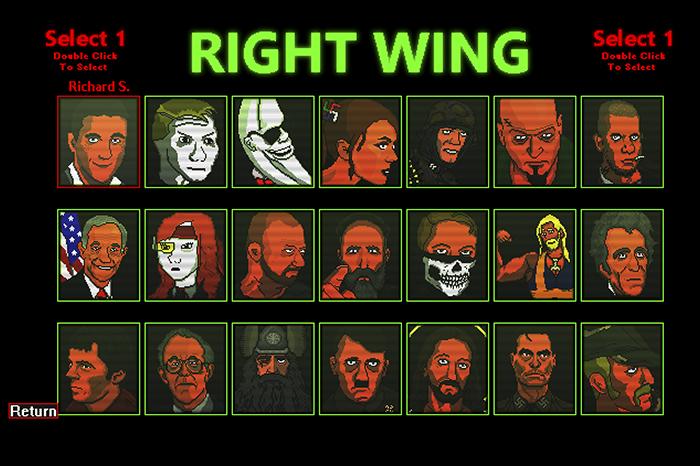

The “Right Wing Death Squad” character selection screen comprises 21 unlockable characters, modelled after well-known new-right figures both fictional and real.

The development of the narrative is tied to the player’s advancement through these levels – each level is completed after defeating a “mini-boss”. This formula is repeated until the player reaches the “final boss”, whose defeat marks the end of the game. This also signals the end of the narrative – after this, the president is saved, and the win condition is fulfilled.

The players are free to choose their preferred character to play with. Figure 1 shows the “Right Wing Death Squad” character selection screen comprised of 21 unlockable characters, modelled after well-known new-right figures both fictional and real. For example, the game includes characters like George Lincoln Rockwell, founder of the American Nazi Party and Moon Man, an unofficial parody of 1980s McDonald's mascot Mac Tonight, which became associated with reciting racist parodies of rap with a text-to-speech voice reciting.

The number of characters a player can play within one run is tied to their selected difficulty level – the hardest difficulty allows for one avatar and the easiest for three, where the other avatars serve as “backup” lives to continue the game if the previous avatar has fallen in battle.

Figure 1: the character selection screen.

Angry Goy II as metapolitics

I argue that Angry Goy II heavily borrows the procedural form of a well-known existing game genre – becoming a reskinned product that, as such, produces little to no procedural rhetoric of its own. Its visual imagery (or to borrow Juul’s terminology – its fiction) is its main element of expression. The game is thus best understood as a metapolitical tool furthering the ideology of the new right.

The concept of metapolitics was elaborated by de Benoist and the French New Right, arguing that political power is legitimized by an ethical framework shaped by the specific culture of a group. As such it states that politics is inherently tied to culture - in order to change the political landscape, a cultural battle must first be won, by transforming commonly held values, ethics and norms and their expressions in the public sphere, so as to create a hegemony consisting of one’s own ideological perspective.

However, as Angry Goy II takes inspiration from 80s shoot-em-ups and was created as a piece of independent freeware, its crudeness or simplicity can possibly be attributed to the faithful replication of the 80s shoot-em-ups or the limited programming capabilities of the developers. Therefore, I will proceed with an analysis consisting primarily of the visual rhetoric, with attention to procedural elements which transcend from its borrowed base to mount a persuasive statement.

Violence and Victimization

Angry Goy II contextualizes the player’s actions immediately upon starting the game in form of verbal rhetoric, appearing as an opening text: “Left-wing terrorists are holding the president hostage… But there is hope…” – upon which the player can control their character to embark on a quest to save the president. In order to succeed, the player must fight and prevail over countless enemies, attempting to reach the president at all costs and defeat his captor.

This approach is encouraged through the game’s mechanics – the HUD is equipped with a meter to track the number of kills against enemies, and the procedural element that differentiates the playable characters is by type of weapons they wield. As such in both the ludic and narrative elements of Angry Goy II, violence is contextualised as a necessity. According to McKinney this constitutes a form of “weak violence”; which means that violence is used as a device – the use of it is allowed as a reaction towards hostile actions of enemies, (for whom no empathy is created) thus allowing the player to feel uninvolved with the expression of it (McKinney, 1993).

Furthermore, it is worth noting that all NPCs (Non-Player Characters) in Angry Goy II have distinct thematic narratives – they differ in terms of both visual design and verbal expression. While this implies that the developers made effort to alter NPC behaviour based on which group they supposedly identify with, it also creates an opportunity to examine the interpellation of the player’s character. From being labelled a piece of “cisgender heterosexual scum” by rainbow flag waving LGBTQ-agenda activists the one moment, to being called a “white male” by a group of feminists the next – the enemies encountered throughout the game consistently ascribe amoral qualities to the player’s character.

The player’s character is always a ‘silent’ protagonist – the game mechanics make it impossible to speak up or intervene against these accusations.

The ‘mini-bosses’ provide context as they condemn the actions undertaken by the player (who has no choice by definition of the functioning of the game’s mechanics) before engaging in combat with them. Figure 2 displays the ‘mini-boss’ encountered in the LGBTQ club – “Progress Master” accuses the player character of a 'lack of tolerance'. “Red Terror” proclaims that while communism historically concerned equality for the proletariat, they expanded their mission to entail equality for all.

The player’s character is always a ‘silent’ protagonist – the game mechanics make it impossible to speak up or intervene against these accusations. While probably unintended, this creates interesting procedural rhetoric which establishes that sticking up for the white men is unaccepted and abnormal in the virtual world of Angry Goy II, playing into the classic ‘reversed’ racism trope popular among radical ring-wing groups.

Figure 2: Mini-boss of Act 2: The LGBTQ-agenda and headquarter.

The Ideal Western Society

The texts produced in Angry Goy II fit into an anti-Enlightenment tradition of speaking (Sternhell, 2012; Maly, 2018). The linear and hierarchical design of the game and its narrative succeed in casting the “Rootless Cosmopolitan” – who takes his template from the Happy Merchant, a meme which portrays an caricature of a stereotypical Jewish man with a black beard, hooked nose, hunched back and hands being wrung in glee – as the central malicious force behind the plot by implementing him as the archetypical “final boss” of the game.

The infiltration and shutting down of the ‘Fake News Network’, the setting of the fourth act of the game – taps into 'anti-mainstream media' discourses prevalent in new right circles. As such Angry Goy II perpetuates the myth that the media are not independent, but controlled by the left and influenced by Jewish interests, and as such censor right-wing voices.

While dipping into a number of racist tropes, Angry Goy II also presents a future depicting the effects of liberal-left immigration policies.

Act 3 takes place in the ‘Diverse Urban Area’ and serves as a backdrop on which racist tropes play out. From caricatures of the do-rag wearing Black “gangsta” figure to the owner of a shabby Indian deli who hides a turban toting Syrian terrorist in his attic, the NPCs are designed to portray ethnic minorities in the most stereotypical manner. Combined with the impoverished design of the level, it intrinsically links these groups to notions of criminality, social class, and poverty. This, tied in with the name of the level, produces rhetoric which frames diversity and multiculturalism as a failed enterprise.

The “mini-boss” of this level is “The Gentle Giant” – an African-American basketball player only capable of producing animal grunts. At the moment of dying the player is confronted with the message that “western society has fallen”, combined with various video fragments underlining the threat multiculturalism poses to whites.

While dipping into a number of racist tropes, Angry Goy II also presents a future depicting the effects of liberal-left immigration policies. These texts are produced in the tradition of anti-enlightenment ways of speaking – multiculturalism is seen as a danger endorsed through notions of cultural and/or racial equality, yet this is deemed an unnatural state that leads to civil decline and deterioration. The media are represented as an ideological state apparatus, which, on its crusade for freedom and individual rights forsakes the 'happiness' of its people.

Figure 3: A video fragment played upon losing the game.

Games as metapolitics

According to Bogost, Angry Goy II can hardly count as a legitimate political videogame – it is essentially a reskinned and adapted production based on an existing game, which primarily constructs arguments by virtue of its visual rhetoric. As such the game does not permit an experience that allows the player to engage with the logic of a political ideology or order, thereby opening a possibility for its interrogation, disruption or support (Wright & Bogost, 2007).

But the game has has moments in which it successfully builds its own procedural rhetoric on top of its borrowed base – the hierarchical construction of the game quite effectively communicates antisemitic conspiracy theories about the cultural hegemony of Jewish people popular in white nationalist’s discourses. Moreover it frames the American political landscape as a zero-sum game in which feminists and people of colour only win when white males lose, believing their sustenance and safety can only be protected by blood-and-soil nationalism.

When president Trump is rescued, the win condition is met and the player is stated to have saved Western civilization – perhaps revealing its most intricate rhetoric. While the player character is virtually silenced, Donald Trump is (literally) a voice against their common enemies – and by extension, a protector of common values.

When president Trump is rescued, the win condition is met and the player is stated to have saved Western civilization.

If examined from a metapolitical perspective, Angry Goy II – while banned from platforms such as Steam and YouTube - still serves multiple purposes in the struggle for cultural hegemony. When the game was picked up as a controversial news item by mainstream media platforms such as Newsweek and The Daily Dot, these MSN outlets effectively contributed to not only to its mainstream visibility, but also enlarged its impact – eliciting many responses ranging from disapproving comments and news articles to a petition on change.org pleading authorities for the game’s removal. Furthermore, the developers of Angry Goy II were not dependent on these platforms in order to monetize their content as they set up the possibility to directly receive donations in cryptocurrency.

By banning and condemning Angry Goy II, one of its most prominent narratives – the lone wolf fighting a “cartel” of bosses who attempt to stop and silence the player’s character because they do not conform to their viewpoints and values – in a way plays out in real life. The rejection of Angry Goy II and all of its related content reinforces the myth that the media are owned and controlled by Cultural Marxists who, in turn, censor dissident right-wing voices. As such it affirms its own narrative of leftist-controlled media, while also garnering the kind of attention which allows for the dissemination and normalization of alt-right ideas (Nagle, 2017). Furthermore, as videogames are inherently dependent on the means of digital technologies in order to be consumed and disseminated, they arguably are affective, customizable vehicles that make use of low-threshold digital infrastructure in order to spread the ideas they contain.

References

Juul, J. (2011). Half-real: Video games between real rules and fictional worlds. MIT press.

McKinney, D. (1993). Violence: The strong and the weak. FILM QUART, 46(4), 16-22.

Nagle, A. (2017). Kill all normies: Online culture wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the alt-right. Winchester: Zero Books.

Palmer, E. (2018). Neo-Nazi video game lets users murder LGBT people to save Donald Trump. [online] Newsweek. Available at: https://www.newsweek.com/charlotesville-crying-nazi-hosts-video-game-allowing-users-kill-lgbt-people-1212855

Wright, W., & Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive games: The expressive power of videogames. MIT Press.