Humans of Albert Heijn and Anatolia of Migros

How do the consumer identity and the (multi)cultural society shape the commercials?

Just like the AnadoluM - campaign from the Turkish supermarket chain Migros in Turkey, the commercial campaign '365 Dagen Boodschappen' [365 days of doing groceries] of the Dutch supermarket chain Albert Heijn generated a buzz among people in The Netherlands. This analysis covers the hermeneutical interpretation of these two advertising projects from a Barthesian perspective.

Introduction

“Je boodschappen zeggen iets over wie je bent” (Your groceries say something about who you are) is the first sentence of the advertisement campaign that is named '365 Dagen Boodschappen' [365 Days Shopping] by Albert Heijn (AH), the biggest Dutch supermarket chain founded by Albert Heijn in 1887 in Oostzaan.

On the other hand, Migros, as one of the biggest chains of Turkish supermarkets, started a campaign by using local aspects in its advertisements in 2012. The name of the advertisement campaign was Benim AnadoluM which means “My Anatolia” in Turkish with a capital “M” of Migros. This paper interprets the online advertisement campaigns of Albert Heijn - 365 Dagen Boodschappen and Migros - Benim AnadoluM in relation to consumer identity and the (multi)cultural facts addressing the customers, as well as being based on the impact of authenticity in consumerism.

Humans of Albert Heijn

The commercial series of 365 Dagen Boodschapen created a buzz among people in the Netherlands. Each day, a portrait of a person (or a group of people) is shared on social media accounts of AH, such as Facebook, Instagram and Twitter, as well as a website on Tumblr that includes the whole series of 365 portraits. Sharing the portraits on social media, AH generated more attention for the campaign, in such a way that people started to share these portraits on their personal accounts or they left likes and comments.

Everyday I go to a different Albert Heijn supermarket and talk to people who have just done their grocery shopping. – Marije Kuiper

What makes the advertisement campaign far more interesting is the way each photograph portrays people, with a written text about themselves. A preference of food, a hobby, an interest or a real-life incident is mentioned by each person and attached under their portraits, as a way to encourage customers to ‘reveal intimate details of their consumer tastes’ (Hearn, 2008, pp. 210).

AH also made a clip out of the portraits from the professional photographer Marije Kuiper.[1] As can be seen in the images in the clip below, she explains how the process begins with a first sentence: "Everyday I go to a different Albert Heijn supermarket and talk to people who have just done their grocery shopping", and at the end, she strikes a pose in front of the 365 photos she took for the advertisement campaign of AH. People who watch the clip as customers somehow become a part of the process, by witnessing how it took place. It can be interpreted as a way to show how real and natural the making-of process is, with a “sincere” explanation of the way things took place by the photographer.

The similarities between 365 Dagen Boodschappen and the blog of Humans of New York, as well as the popularity they received once, prove that people are highly interested in knowing about other people’s lives. Both projects displayed private and personal issues of people. Starting as a blog, Humans of New York includes stories of different people who are interviewed on the streets of New York. Each day features a photograph and story of another person. Later on, the Humans of New York (HONY) tradition spread around the world to other cities. In that sense, 365 Dagen Boodschappen is very similar to the way HONY shares stories of people. The "about" section of the Tumblr website of the advertisement campaign of 365 Dagen Boodschappen contains these sentences:

“...Over waar je van houdt, voor wie je gaat koken en nog veel meer. En dat is voor iedereen weer anders. Omdat we bij Albert Heijn die verschillen mooi vinden, brengen we elke dag iemand in beeld die net boodschappen heeft gedaan...” (…About what you love, for whom you are going to cook and much more. And that's different for everyone. Because we, at Albert Heijn, like differences, we want to bring someone into view who has just done their groceries, on a daily basis…)."

Highlighting the differences between people, AH follows a strategy by which its customers can be shown that differences in society are warmly welcomed in AH. These differences are the differences of the view, culture, background, nationality or personality of people who are portrayed for the campaign as being members of the different segments of society.

Local Tastes of Anatolia

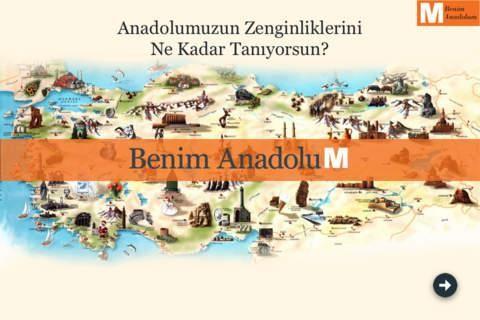

Migros introduced the concept of thematic shopping for the first time in Turkey as Benim AnadoluM (My Anatolia), by offering products from all over Anatolian regions, in every supermarket of Migros from Istanbul to Hakkari, a city in Eastern Anatolia. In Turkey, “local”, as a myth (Barthes, 1957), signifies what is “fresh” and “authentic” as well as “healthy”. Being a country with many local differences, everyone is very interested in local traditions of other people, especially with regards to food. Parallel to that, Migros used the interest in local culture as an advertisement campaign. What makes the campaign even more interesting, is that an online application is offered and is named the Benim AnadoluM App.

As can be concluded from the image above, the online application shows the map of Turkey with specific symbols of traditions shown on it for each region. This has been done in the same way in the advertisement campaign. The question on the image, 'Anadolumuzun zenginliklerini ne kadar taniyorsunuz?' [How much do you know about the beautiful tradition of our Anatolia?], can be interpreted as an eye-catcher, mostly of consumers from the cosmopolitan cities in the West of Turkey, such as Istanbul and Izmir. These cosmopolitan cities are home to many people who migrated from Anatolian cities, either for employment or for other reasons. Customers can also learn the cultural facts of each region, and they receive traditional recepies via the app.

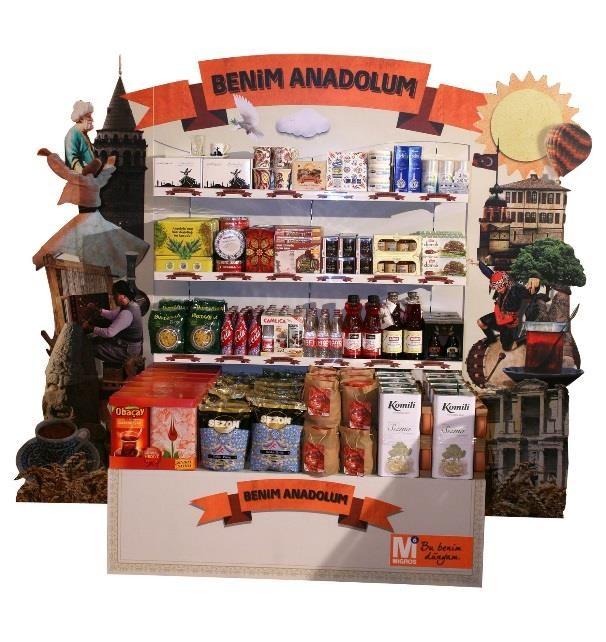

In almost every Migros supermarket, shelves, as in the image above, were filled with traditional food products with motifs related to the theme of 'Anatolia', only for the campaign. The styling consists of historical buildings, famous figures and products, such as Turkish tea from the Black Sea region and the olive-oil from the Aegean region. Commenting on their campaign, Cem Rodoslu, the Deputy Managing Director of Migros then, mentioned;

"Anatolian tastes were introduced to the consumers in all corners of Turkey with this campaign. We removed all the obstacles between the consumers and these tastes. It is now enough for the customers to go to Migros stores in the cities to be able to access to the specific tastes of the ancestors" (Migros Kurumsal, 2012).

Anatolian tastes were introduced to the consumers in all corners of Turkey with this campaign. We removed all the obstacles between the consumers and these tastes. - Cem Rodoslu

It is important to point out that Rodoslu highlights the way Migros provides their customers an “authentic” way to taste what they want from far-away places, an experience which is normally only made possible by being physically there, in the different regions of Turkey.

Authenticity as a Marketing Strategy

Increased popularity of social media has affected the self-presentation of people. Having a certain lifestyle and showing different aspects of oneself in every detail on social media platforms are nowadays perceived as ways to have an “authentic” life. The desire of people to experience and to engage themselves in authentic lives has affected marketing strategies. This becomes visible in the advertisement campaign of 365 Dagen Boodschapen, which involves ‘a detachable, saleable image or narrative, which effectively circulates cultural meanings’ (Hearn, 2008, pp. 198).

Having a lifestyle and showing different aspects of oneself in every detail on social media platforms are nowadays perceived as ways to have an “authentic” life.

The way AH uses portraits of people as a way to make consumers feel like; “these are not insincere photos of celebrities acting in commercials, but they are ordinary people like one of us” is a remarkable project. What makes this campaign authentic is not just the way it shows people’s interests or lifestyles, but also their backgrounds and nationalities, such as in the images below. The first person pictured is from Iraq and has lived in the Netherlands for thirty years now. He mentions that he sometimes misses his country of origin, the country of “honey and butter". The second person is from Turkey and compares The Netherlands with Istanbul, by saying that the whole population of The Netherlands equals to just the city of Istanbul in Turkey.

Another interesting part of the advertisement campaign of AH is that there is a recipe included of each person who is portrayed. The recipes include specific products one can find in AH, as is expected. Moreover,, the portraits of people who are from other countries mostly offer international recipes. Other than recipes, people from other countries are mostly portrayed in their traditional clothes. Through such a mythical construction, AH highlights the strategy of serving different cultures and tastes and having a variety of products from all over the world. They themselves state the following: “Omdat we bij Albert Heijn die verschillen mooi vinden” [Because we, at Albert Heijn, like these differences].

The authenticity of the portraits is constructed through portraying customers who just finished their shopping and are smiling in front of a AH store in one of the cities of the Netherlands. Everyone is happy and smiling and the happiness is closely related to consumer culture. One customer is happy because she can find products native to her own country (as in the first image below), by mentioning that she is from Jakarta, she likes cooking Indian food and she is happy that she can buy almost every ingredient in The Netherlands, thanks to AH.

Another customer, in the picture below, is happy since she can do her religious ritual during Ramadan, with a specific product that can be found in AH. She even makes a wish when she states that: " Het zou mooi zijn als de dadels tijdens de Ramadan in de Bonus zouden zijn [it would be nice if we could buy more dates with Bonus -the discount card of AH- during Ramadan]".

Not only do they pose before the camera; they also give information about themselves, which is something “real” and “authentic”.

Not only do they pose before the camera; they also give information about themselves, which is something “real” and “authentic”. Moreover, they make their private life public, through sharing their stories. This is related to the strategy that the more authentic the representation is the more real we should consider it to be (McCrone et al., 1995, pp. 46).

For instance, the couple smiling in the image below share the story of their first meeting: "Zij is half Spaans, half Egyptisch, ik kom uit Madagaskar, we wonen in Amsterdam en hebben elkaar in Londen ontmoet! [She is half Spanish, half Egyptian, I am from Madagascar, we live in Amsterdam and we met each other in London!]".

All of these examples show a specific mythical signifier (Barthes, 1957: 127). They are made of meaning and form, that constructs the authenticity under the very effect of “locality”. Every single aspect discussed so far is part of the mythical construction, such as the traditional recipes given by these people, the identifying cultural objects, clothes or accessories they carry (being black, showing multicultural couples, having the Muslim head scarf or the Indian “Dastar”, mentioning their country of origin) or any signifier addressing the specific cultural background of consumers.

The mythological construction transforms history into nature (Barthes, 1957: 127), as Barthes points out, since all these people from different countries, once migrants, being “the other”, are depicted as if they adapted their cultural and culinary traditions to the everyday living of The Netherlands and are feeling happy with that. Such mythical constructions work through addressing the reader, in this respect: the consumer. The customer not only sees the ordinary people on the advertisement campaign, they also see that their culture is part of the culture of AH. What AH tries to do, is to show that they are open to these different cultural tastes. All cultures arepart of the “locality”, by welcoming differences as something wonderful, which is a perfect strategy to provide consumer satisfaction, through intimate recognition of everybody equally via “locality”.

When it comes to the advertisement campaign of Benim AnadoluM (My Anatolia), employers created a very authentic atmosphere in different supermarkets of Migros in Turkey. For instance, in one of the supermarkets, a “kina gecesi - henna night”, which is a part of Turkish traditions before the wedding ceremony, is staged by Migros employees while people were shopping. In another store, a traditional dance group suddenly started to dance a Turkish folkloric dance, whilst wearing traditional clothes. Taking this into consideration, Migros used the providing of an authentic experience as a marketing strategy.

The authenticity derives from the fact that even though these traditions are part of Turkish culture, they are, usually not experiences that are common in the daily lives of Turkish people, especially of those living in the cosmopolitan cities. Seeing a scene which displays part of one’s cultural tradition creates a rather emotional “affect-like” moment. This makes consumers think of their hometowns, if they're far away. At the vey least they will learn about another cultural tradition, that belongs to their nation and its history, which is rather important for most of the Turkish people.

Similar to the AH campaign, Migros also benefits from the strategy of localizing their products through mythical signifiers (Barthes, 1957), such as traditional dance figures and clothes, traditional symbols on products and, most importantly, the chance to have a live experience of all of these things while customers are shopping. That being said, Alison Hearn’s ideas on branding practices are also very relevant to the situation in the advertisement campaign of Migros as an authentic experience, in which consumer behavior and lived experience become ‘both the object and the medium of brand activity’ ( Moor, 2003, pp.42).

Not only food, but also other cultural aspects are used as authentic tools of strategy within the Migros advertisement campaign. For instance, the first image above shows symbols that represent each region of Turkey, which is also written on the image; Anadolu Türküleri – 7 bölge, 21 türkü (Anatolian songs – 7 regions, 21 songs). Even though Migros has nothing to do with music, they use it strategically to attract their customers' attention, by giving them a reason to relate themselves to one of these regions. In the clip of the advertisement campaign, they used traditional Turkish music in the background.

Another interesting strategy used in the clip, is the person who explains several Turkish traditional food products in English, while walking around the Migros store. This person is an American, who is a well-known English teacher. Preferring a person from another country, as experiencing “the other”, to play a role in the advertisement clip while highlighting local products, is another strategy based on authenticity. He talks about traditional motifs by saying “you can even find traditional motifs on the daily products you use in Turkey” as if the content was not from an advertisement of a supermarket chain, but from a touristic travel program on television.

Locality and authenticity as a marketing strategy

In light of the examples discussed so far, locality is used as a marketing strategy while addressing customers through constructing (multi)cultural aspects as mythical signifiers. As the advertisement campaign of 365 Dagen Boodschappen shows, no matter howpeople were portrayed, real or fake, consumerism is idealized through making private lives public and using the self in order to make it a promotional object for advertisements. One of the consequences of consumer culture in the age of neoliberalism as well as digitalization is that authenticity has become today’s most strategically used marketing tool, which is apparent in both of the advertisement campaigns discussed so far.

The will to engage in traditional practices and to experience customs and different tastes are also strategically used to affect customers, such as in the case of the Benim AnadoluM campaign of Migros. The highlighted concept of being “local” in the Benim AnadoluM campaign stands for concepts such as: natural, fresh and healthy (from the countryside), which are also among the concepts that are highly valuable and popular for today’s society. Creating a local lifestyle, which has happened in both of the examined case studies, would be criticized by Barthes as a mythical construction, based on his claims on the mythical use of wine as something signifying the Italian or French local culture and their healthy lifestyle. That same wine, however, can also be seen as an unhealthy product.

Even though the two examples differ from each other in some aspects, both campaigns use locality as a strategy. This is mythically constructed by AH through specific signs of the culinary traditions of each consumer. These people all have different multicultural backgrounds, whereas national traditions, which are a rather emotional and meaningful way for Turkish people to experience locality, are used as the mythical construction by Migros. The practices of “becoming” and “experiencing” are the characteristic actions of the consumerist society, which pave the way for companies and brands to benefit from it as a marketing strategy as in both cases which were focused on in this article.

References

Barthes, R. (1957). Myth Today. In Mythologies. New York: Noonday.

McCrone D., Morris A., Kiely R. (1995). Scotland--the Brand: The Making of Scottish Heritage, Edinburgh University Press.

Moor, Elizabeth. (2003). Branded Spaces: The Scope of New Marketing, Journal of Consumer Culture 3(1): 39-60

Hearn, A. (2008). Meat, Mask, Burden: Probing the contours of the branded 'self'. Journal of Consumer Culture, 8 (2), 197-217.

Van Nuenen, T. (2015). Here I am: Authenticity and self-branding on travel blogs. Journal of Tourist Studies. 1-21.

Migros Grubu "Perakende Eğlenceli Bir İştir" Dedi / 09.03.2012. (n.d.).