The Hybrid Artist: An All-Rounder in the Cultural Field

The Hybrid Artist, as described by de Winkel et al. (2012), is an artist that uses ideas from different disciplines to expand their practice and explore different creative roles. This hybridity blurs the boundaries between ‘fine’ and ‘applied’ arts and artists and cultural actors, creating a tension between autonomy and heteronomy. The hybrid artist is engaged in their own world of artistic creation but also aware of the world outside their own framework, and feels the need to establish himself as such. The artist is not bound to one discipline to convey their conceptual ideas. To extend their practice even more, artists make use of (social) media to establish themselves within the art world, and produce a posture that fits their work.

To explore the idea of the hybrid artist, I will analyze the work and posture of visual artist Olafur Eliasson. Eliasson is one of the most well-known contemporary artists; his practice crosses disciplines and addresses societal issues such as climate change. I will aim to answer the following question: how can we understand Olafur Eliasson in his practice and the media through the lens of the hybrid artist?

The Hybrid Artist

The romantic idea of the artist working in his studio has given way to a new socially, engaged artist. In their book The Fall of The Studio, Davidts et al. (2009) connect this notion of the artist working outside of his studio to the emergence of new art forms that are site-specific, based on ideas, or in need technical assistance in their creation. This leads to the studio becoming a space for thought, rather than creation. Furthermore, it seems as though “some artists simply stopped making works themselves and began outsourcing the production of works of all kinds and scales to engineering firms and industrial manufacturers” (p. 3-4).

This implies that the ‘fallen’ studio and the emergence of new art forms contributed to opening up the arts to outsourcing, interdisciplinarity, and hybridity. It also emphasizes that ideas and conceptual frameworks within the arts have gained importance over aesthetics and craftmanship. That many of these artists have the potential to contribute to societal issues is partly dependent on a hybrid practice that does not rely on form, but rather on the concept.

Thierry de Duve (1998) has stated that art in general, or art at large, takes the essence of art away from the specific to the generic (p. 152). The aesthetic criterium, in which art needs to conform to being an object of beauty has faded, and rules regarding what is and what is not art fail to distinguish both categories. The judgment of the public and the artist determines what is art and what is not (de Winkel et al., p. 25). This implies that distinction between disciplines is no longer needed: “you can now be an artist without being either a painter, or a sculptor, or a composer, or a writer, or an architect—an artist at large” (de Duve, 1998, p. 154).

Even in this post-medium condition, artists continue to struggle to make a living. In their research, van Winkel et al. (2012) explain how artists are often required to get their income from jobs outside their artistic practice. For many, this meant working at a restaurant or bar or as a teacher. Post-industrialization, many artists turned to disciplines within the cultural field to provide extra income. Artists' creative and artistic qualities have proven valuable within many fields. Artists have turned to graphic design, teaching art courses, furniture design, or other commercial purposes that are regarded as "applied" art forms. Usually, these practices are parallel to the artist's autonomous practice. However, within a hybrid practice, the boundaries blur until they are indistinguishable from one another. In other words, hybridity entails that the artist works not only interdisciplinarily, but combines autonomous and applied art forms in his practice (van Winkel et al., 2012, p. 10-11).

The distinction between what I will refer to as "fine" arts in comparison to applied art forms goes beyond the medium. Fine arts are those that have an intrinsic value as an art object, while applied arts have a functionality that goes beyond their aesthetic or conceptual frame. Architecture, design, film, and illustration are some of the forms not bound to the sphere of fine arts. On the other hand, painting, sculpture, some forms of photography, and film are disciplines mostly used in the fine arts realm. Interdisciplinarity in regards to medium is as such something different - a hybrid practice in which different art forms are combined. But, to distinguish these from each other will prove more difficult in practice.

Media and Visibility

The the hybrid artist's posture is not constructed by artistic creation alone. It is helpful to see how hybridity is shaped within the artist's presentation to the outside world. Media outings, like interviews and social media, can deepen an understanding of the artist's conceptual framework as well as increase visibility. Visibility is important in creating opportunities for subsidization or exposure which could provide income for the artist. This exposure takes place in what Pascal Gielen calls the civil space, a space in which recognition and public value is important. Apart from visibility, the civil space asks artists to reflect on their practice. Why is their work considered art, and why it is important to be seen (Uniarts Helsinki, 2016, 24:46-27:05)?

However it should be taken into consideration that an artist that uses media to gain fame, or even present himself as a celebrity, might lose authenticity by focusing on this public persona. The implication is thus that when the artist wants to supply the audience with its demands regarding his work, he might have nothing left to offer (van Winkel et al., 2012, p. 31). The civil space, in this way, is needed to reflect on new ways of explaining and exploring the artist's practice, so that he does not get stuck in a cycle of showing the public only what is appealing at that moment. The artist should be in constant consideration of what he shares with the public and continue reflecting in order to engage in a practice that allows new inspiration to evolve.

Visibility can shape the artist into someone who reflects on artistic and societal issues with the public. The so-called public intellectual “intervenes in the public debate and proclaims a controversial and committed and sometimes compromised stance from a sideline position. He has critical knowledge and ideas, stimulates discussion, and offers alternative scenarios in regard to topics of political, social and ethical nature, thus addressing non-specialist audiences on matters of general concern” (Heynders, 2014, p. 3).

By using multiple platforms and disciplines, such as artistic practice, the museum, and (social) media, to share knowledge and ideas, the hybrid artist has the potential to cross the boundary into public intellectual. Visibility and fame give the artist the potential to gain prestige. As Heynders (2014) explains, “the intellectual grounds his authority and interdependence in the autonomous world of art or philosophy, but on the basis of his prestige he can also interfere in political life” (p. 9). This could deepen the practice of the hybrid artist by implementing public engagement into his practice. In this way both fields, that of autonomy and engagement, complement each other.

Engagement is an important notion when reflecting on society, but this does not necessarily mean a loss of autonomy for the artist. As Denis (2007) explains, “autonomy ceases to refer to a literary work considered as a goal in itself, and becomes the condition for the social presence of the writer. This is because he or she is a priori free to write anything, that is, entitled to ‘unveil’ the world” (p. 39). I will consider an artist as autonomous when he is responsible for making a work that is created to contribute to the art world conceptually and aesthetically. This does not necessarily mean that a work should be regarded as skillful or beautiful, but rather that the artist uses a visual frame to deepen his conceptual ideas about art and society. Autonomy is, in this respect, not something that is gained or lost through the presence of the artist, it is something internal to the work. The creator of an autonomous work provides a posture in which the artist can act autonomously within other fields. He or she precedes the work and can intervene in society while maintaining the posture of an autonomous maker. Since hybridity blurs the boundaries between autonomy and engagement, it provides for a useful posture to explore a conceptual framework rather than aesthetic values.

Olafur Eliasson's Practice

Figure 1: The weather project (2003)

Olafur Eliasson (1967) is one of the most successful artists working today, with major exhibitions all over the world. One of his best-known works, The weather project (2003), was shown at the Tate Modern in London. It consists of a large, artificial sun that lights up the Turbine Hall. Eliasson’s practice shows hybridity in the sense that he works as an artist that uses many different disciplines and is supported by his studio (Studio Olafur Eliasson).

The use of science, architecture, design and nature are intertwined in his practice and are more or less equal to each other. On his website he states: “Olafur Eliasson’s art is driven by his interests in perception, movement, embodied experience, and feelings of self. He strives to make the concerns of art relevant to society at large. Art, for him, is a crucial means for turning thinking into doing in the world. Eliasson’s works span sculpture, painting, photography, film, and installation. Not limited to the confines of the museum and gallery, his practice engages the broader public sphere through architectural projects, interventions in civic space, arts education, policy-making, and issues of sustainability and climate change” (Studio Olafur Eliasson, n.d.).

Apart from this, he works as a teacher and collaborates with others from both in- and outside of the art world. His project Little Sun (2012), in which he developed portable, solar-powered lamps that provide light for people without electricity in Ethiopia, is one of the projects in which his social engagement is most visible. His diversity of disciplines is described by Rachel Cooke in an interview in The Guardian (2018): “But usually he works on an almost preposterously grand scale, across all media, and oblivious to barriers of any kind, whether psychological or physical. In 1998, he used uranin, a dye used to detect plumbing leaks, to colour a Berlin river green. In 2008, he created four huge manmade waterfalls in New York harbour. In 2011, he designed the exterior of Harpa, Reykjavik’s new concert hall, a soaring cliff of hexagonal glass tubes and mirrored panes inspired by Iceland’s volcanic geology” (Cooke, 2018). This description suggests that like the hybrid artist, Eliasson is more interested in expanding his practice than distinguishing between disciplines. He does not shy away from creating work that ranges from interventions in the public space to museum installations to architectural projects.

That he is interested in the expansion of his conceptual frame becomes explicit in the Guardian interview: “I don’t think my scope is wide enough. My projects are all connected. There’s a high degree of synchronicity. And I have a lot of confidence in things like abstraction, so it’s not a big step for me to move from one medium to another” (Cooke, 2018). Widening his vision on the important aspects of his practice means the medium is no longer important. Further the fact that he regards all of his projects as ‘connected’ suggests that concept transcends discipline.

To dive deeper into medium's loss of meaning, we can look at the importance of engagement for Eliasson’s work. He states: “The hierarchies are changing. I can see the cultural sector taking on more leadership when it comes to shaping the world in the future” (Cooke, 2018). Within a changing world, Eliasson believes that the cultural sector should take responsibility as a field in which change and awareness are possible. To underline this claim we can compare three of Eliasson's works from that are each embodied in a different discipline.

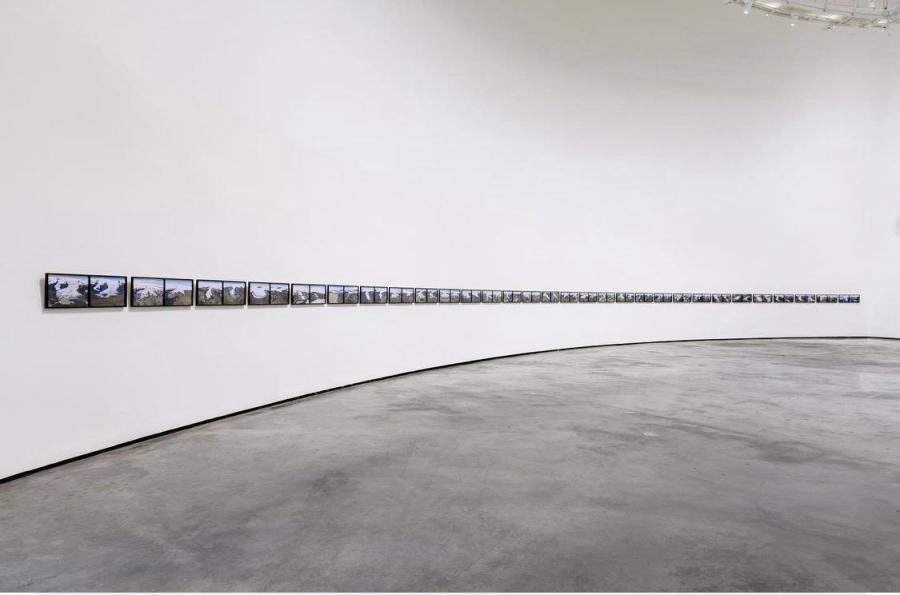

The work below, The glacier melt series 1999/2019 (2019) (figure 2), was part of the exhibition In real life (2019), in the Museo Guggenheim in Bilboa. For this work, Eliasson photographed the same glaciers twice, once in 1999 and once twenty years later. The work shows the impact of global warming on Icelandic glaciers in a museum setting.

Figure 2: The glacier melt series 1999/2019. (2019)

Figure 3 shows the work Ice watch (2014), in which Eliasson moved massive blocks of ice from glaciers in Iceland to the streets of London. Here, the ice laid in the sun, slowly melting. The work is set in a public space but concerns the same conceptual framework as the work above. The work is more explicit, more direct, and the temporal character has a different connotation than The glacier melt series 1999/2019.

Figure 3: Ice watch (2014)

In figure 4, we can see a picture of Eliasson’s work, WUNDERKAMMER (2020), part of the augmented reality app ACUTE ART. This work consists of digital works that can be projected into any space desired using your smartphone. Eliasson created a sun that can be placed wherever and whenever the app user feels it belongs. Yet again, Eliasson draws on nature, this time brought even closer to the spectator by non-traditional methods.

Figure 4: WUNDERKAMMER. (2020)

The examples above suggest that while remaining within the same conceptual discourse, e.g. climate change and human perception in contrast with nature, can flow across different disciplines. Blurring the boundaries between these disciplines contributes to what Eliasson sees as ‘widening his scope’.

That hybridity is inherent to the pure idea of his work is underlined in the following sentence: “You have an idea…an intuition, a feeling, a subconscious thing. It comes in many versions, but when it does it is sometimes better to go back and ask where it came from than to immediately decide where it is about to go” (Cooke, 2018). Eliasson shows here that the medium or discipline is secondary to the origin of the idea, connecting his artistic practice to the autonomy inherent to the artist.

The Engaged Artist

The boundaries between autonomy and engagement can be analyzed further by the position Eliasson takes on societal issues. Figure 5 is an Instagram post from Studio Olafur Eliasson, in which he responds to the outcome of the U.S. presidential elections. He congratulates the country on the election of Joe Biden and how this will benefit “Climate, health, poverty, social injustice and truth” (@studioolafureliasson, 2020). He uses his artistic prestige to comment on societal issues, therefore functioning as a public intellectual. The reference to climate change shows that his engagement is substantiated and derived from ideals visible in his artistic practice. I would suggest that the hybridity in his practice goes beyond even the cultural sphere and stretches to that of politics.

A loss of authenticity and public saturation through presenting them with the images they demand of the artist is a potential downside of being visible on social media. Eliasson, however, chooses to present his work on Instagram with elaborate explanations. Alternating these with posts on societal issues underlines his presence as a public intellectual and preserves his authenticity.

Figure 5: post from Instagram page Studio Olafur Eliasson regarding the outcome of the U.S. presidential elections

The hybrid artist's posture originated from the lack of paid labor available to autonomous artists and the need for creativity within other fields of society. Artists using their creative capacities in other disciplines have therefore stretched their conceptual framework accordingly. By focusing on concept rather than form, the boundaries between autonomous and applied art forms blur, and the artist's practice becomes hybrid. The tension between autonomy and engagement can be further explored by focusing on the media presence of the artist in question. How do they engage with societal issues, and how do they conform to other related postures, like the public intellectual? Hybridity is no longer bound to creating a practice that can provide an income for the artist, rather, it is a way of organizing an interdisciplinary art practice. As we can see from analyzing the work and (social) media presence of Olafur Eliasson, a hybrid practice can deepen the practice of the socially aware artist.

References

Cooke, R. (2018, March 22). Olafur Eliasson: ‘I am not special.’ The Guardian.

Davidts, W., Paice, K., Gelshorn, J., Marks, M., & Swenson, K. (2009). The Fall of The Studio: Artists at Work (Antennae) (0 ed.). Valiz.

Denis, B. (2007). Criticism and engagement in the Belle Époque. In G. J. Dorleijn, R. Grüttemeier, & L. K. Altes (Eds.), The autonomy of literature at the fin de siècles (1900 and 2000) (pp. 29-40). Peeters.

Duve, T. (1998). Kant After Duchamp. Amsterdam University Press.

Eliasson, O. (1999–2019). The glacier melt series 1999/2019 [Photographs]. Museo Guggenheim, Bilbao, Spain.

Eliasson, O. (2014). Ice Watch [Site-specific installation].

Eliasson, O. [studioolafueliasson]. (2021, January 21). Just watched President Biden on his first day signing the USA back into the Paris Agreement! [Instagram post]. Instagram.

Eliasson, O. (2003). The weather project [Installation].

Eliasson, O. & Acute Art. (2020). WUNDERKAMMER [Augmented reality app].

Heynders, O. (2014). Transformations of the Public Intellectual. In Writers as Public Intellectuals: Literature, Celebrity, Democracy (1st ed. 2016 ed., pp. 1–25). Palgrave Macmillan.

Uniarts Helsinki. (2016, March 15). Pascal Gielen – The hybrid Artist and Arts Education beyond Art [Video]. YouTube.

van Winkel, C., Gielen, P., & Zwaan, K. (2012). De hybride kunstenaar. De organisatie van de artistieke praktijk in het postindustriële tijdperk. AKV | St. Joost. https://lectoratenakvstjoost.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/eindrapporthybr...