Privacy, Periods Risks and a Digital Dystopia in a post-fall Roe v. Wade US

The femtech industry has witnessed a significant surge in period-tracking app usage over the past decade, offering users the convenience of monitoring intimate details like ovulation, mood swings, and sexual activities. Termed reproductive health data, this sensitive information poses privacy risks, particularly in jurisdictions criminalising abortion, impacting women's privacy and bodily autonomy, especially post the Roe v. Wade reversal in the US.

Roe v. Wade reversed

For the last five decades, Roe v. Wade guaranteed women the right to an abortion in the US. This 1973 landmark Supreme Court case legalised abortion nationwide, effectively recognizing a woman's constitutional right to privacy regarding reproductive choices. However, in June 2022, the Supreme Court reversed this right, granting states complete control over abortion regulation. This historic overturn has raised concerns about privacy and surveillance within the context of period tracking apps used by women in the US. Abortion deeply resonates with the US conservatives. Among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents who advocate for abortion ban in most or all circumstances, a substantial majority (78%) identify as conservatives (Lipka, 2022). And, with conservative-led states eyeing potential abortion restrictions, period tracking apps might find themselves in a data-sharing dilemma, exposing the abortion histories of their users. This paper aims to investigate privacy risks and surveillance issues related to women's health data on period tracking apps in a post-fall Roe v. Wade US.

Privacy & Surveillance Risks: Post-Roe Tracking

Using Sandra Petronio's Communication Privacy Management (CPM) theory and exploring Surveillance Capitalism, we will delve into the potential risks associated with period tracking apps, with a specific focus on an app called Flo, its stakeholders, and its existing privacy policy. Examining these apps reveals how states that have banned or are likely to ban abortion could utilise reproductive data to identify women who have undergone abortions, thereby infringing on their privacy. Furthermore, understanding how such apps collect, store, and possibly share this data is crucial for assessing the privacy risks and implications of abortion-related policies.

The concept of privacy is subjective and diverse, to say the least. People have different views on privacy depending on where they are, who they communicate with, and how their information socially and culturally affects them. As they navigate these public and private spheres, they start establishing boundaries, thereby adding different definitions of privacy. However, regardless of what privacy means to them, they believe it is their fundamental right to what information to conceal or reveal (Petronio, 2002, p.2). Sandra Petronio (2002) refers to this navigation of boundaries as Communication Privacy Management. This theory is crucial to understanding how individuals view privacy concerning their data on period tracking apps. Data on period cycle apps is sensitive. Therefore, when one uploads their intimate data on such apps, it is with the knowledge that their reproductive health data is private and is theirs alone.

When one uploads their intimate data on such apps, it is with the knowledge that their reproductive health data is private and is theirs alone.

In today’s digital world, any behavioural data can be commodified by big corporations, leading to surveillance capitalism. Shoshana Zuboff (Democracy Now, 2019) describes the concept of surveillance capitalism as the commodification of private human experience. As we leave a digital trail of our behavioural data and patterns, companies latch on to it for their benefit. Period tracking apps not only help monitor period cycles but are also nearly accurate when it comes to predicting the next period cycle. However, this algorithmic prediction is a result of the vast private health information one feeds into the apps. Data stored in such apps is a goldmine for advertisers and third parties. Subsequently, the accumulation of data makes users vulnerable to data breaches and privacy risks at the hands of big corporations.

CPM and surveillance capitalism largely intersect with period-tracking apps as the former enables individuals to establish boundaries, and the latter violates those boundaries, causing turbulence. In the wake of Roe v. Wade being overturned, several women realised the threat their health data posed and quickly deleted their period apps and urged others to do so on many online platforms. Some popular period apps even updated their privacy policies and shared them on social media platforms to pacify users' concerns.

This paper will apply the above-mentioned theories and discuss in brief the reasons why women use period tracking apps, how they navigate privacy boundaries with their reproductive data, and its potential threats in a post-overturning of Roe v. Wade in the U.S.

Data and analysis

The data for the analysis was collected from a popular period app in the US called Flo by using an app walkthrough method. This study delves into Flo's collection of menstrual data, and user-input requisites, and examines its privacy policy sourced from the Flo website. By applying the concepts of CPM and surveillance capitalism to the data, we will gain insight into its data-sharing practices and the implications of health data collection, particularly in light of the Roe v. Wade case reversal. This paper will therefore analyse the type of health data Flo collects, and some key details outlined in its privacy policy. The research was conducted from May 20 to May 26, 2023.

The digital trail of women’s reproductive health data

Tracking period, ovulation, and pregnancy on Flo

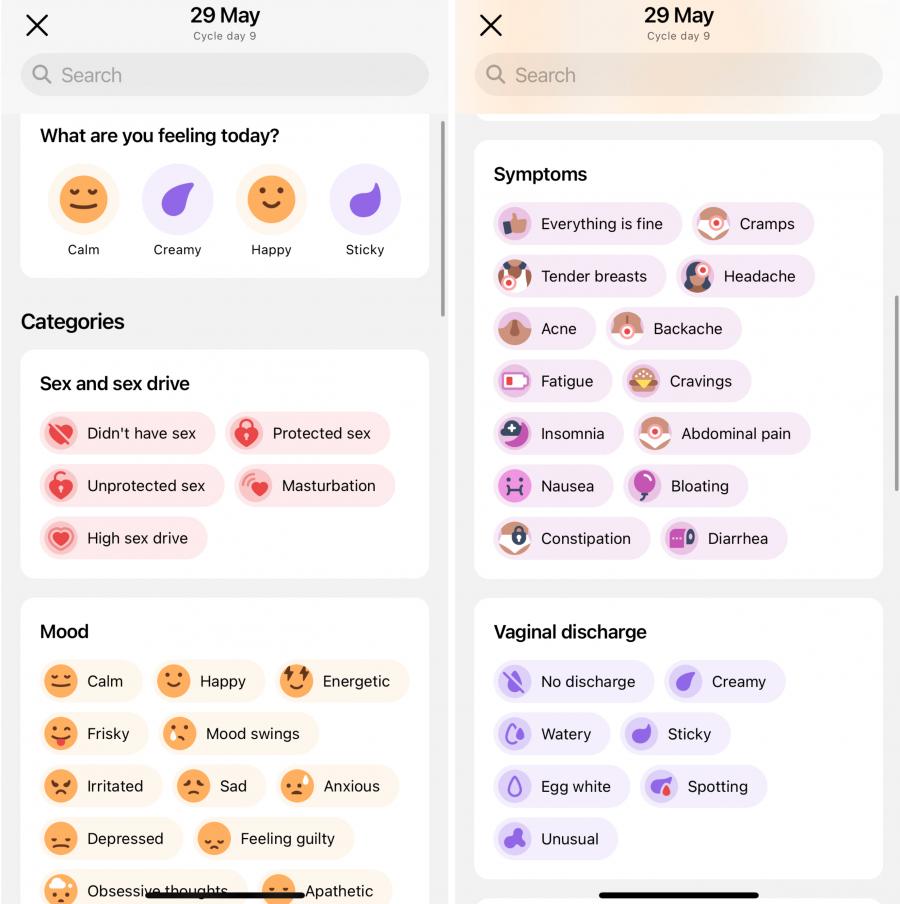

Flo is a popular US-based health app used to track periods, ovulation, and pregnancy. It has more than 100 million downloads and high ratings on the Google Play Store. As the user signs up for the app, they are encouraged to enter more data on their reproductive health in detail ( see Figures 1 & 2). The data ranges from sex drive to water intake. While it is not mandatory to disclose everything, users do so due to the convenience of having their reproductive health information at their fingertips. Users decide how much information to disclose depending on what they want out of the app (Petronio, 2002). In this case, the information disclosure of sensitive data like ovulation, pregnancy test, and sex drive is purely to get predictions or insights about their reproductive health; which means this app can also tell when a pregnancy starts or stops.

Figure 1: Type of reproductive data Flo collects

Figure 2: Type of reproductive data Flo collects

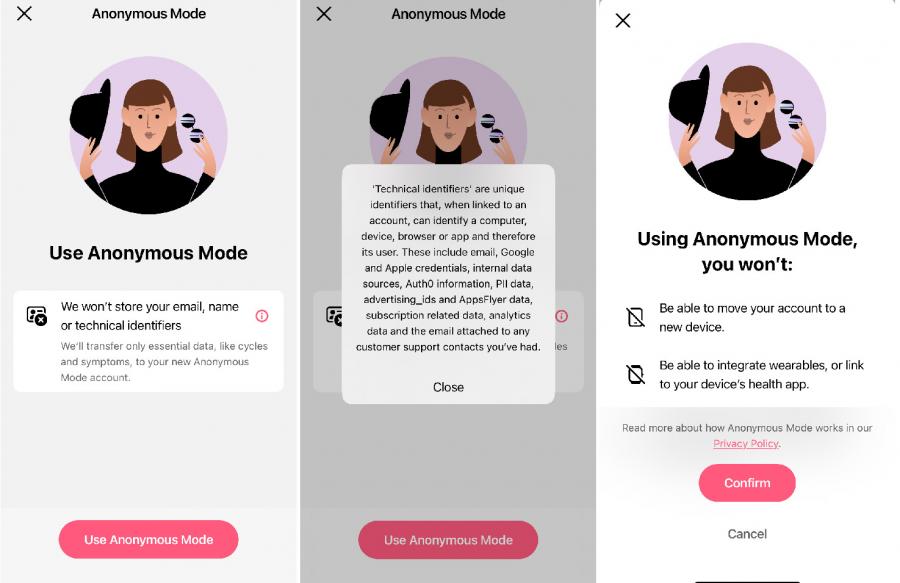

Private but T&Cs apply

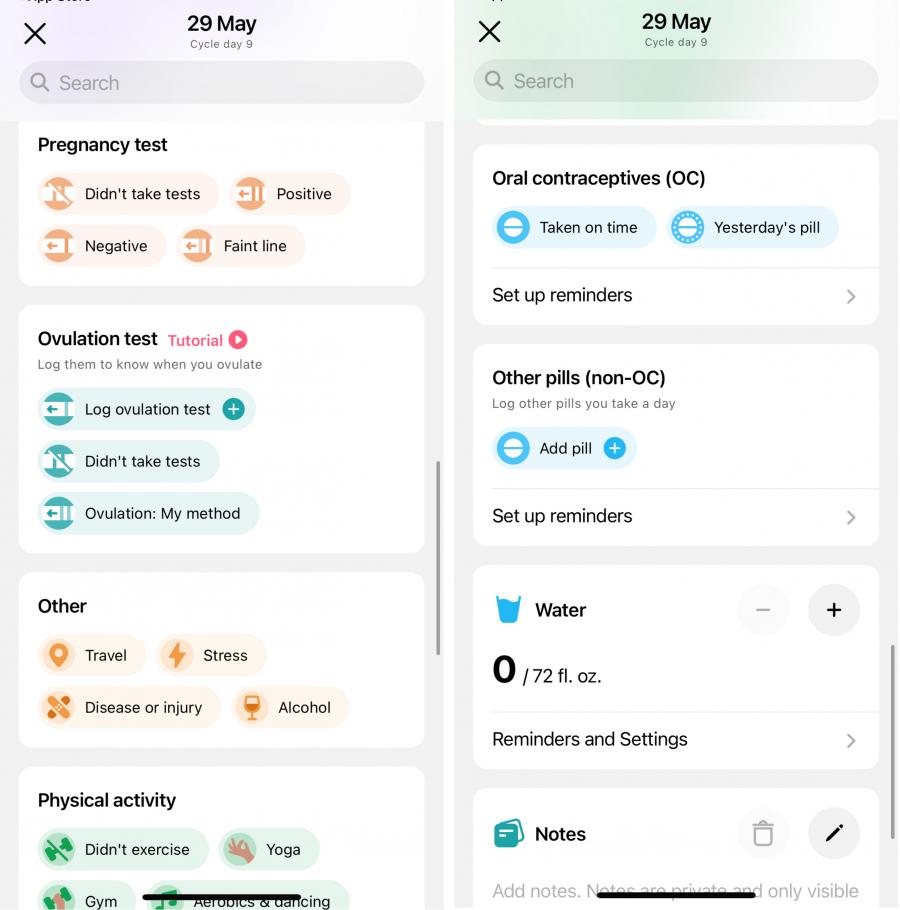

Like every other app, before signing up on Flo, one must consent to data processing under the terms of their privacy policies. Apps have their privacy policies in terms of what data is being shared or sold to third parties. Flo’s updated privacy policy post-overturning of Roe v. Wade, mentions they do not sell or share an individual’s data with third-party apps or advertisers. Users who want to experience other features or service offerings, can consent to them or withdraw anytime, as seen in figure 3. If someone consents to it, only their non-health personal data is shared with a third party for marketing purposes, as mentioned in their privacy policy (figure 4). Within the first step of registering on the app itself, individuals believe that the data they feed would be their private property and therefore trust the app with their intimate data. Managing privacy boundaries gives them the freedom to control the flow of their private information (Petronio, 2002). Therefore, by agreeing to the terms and conditions, they are also consenting to co-ownership of their data to companies. However, when users share their reproductive data with period apps, they expect companies to protect and treat their data in a certain way (A First Look at Communication Theory, 2014).

Figure 3: Flo's privacy & T&Cs agreement page

Figure 4: Snippet of Flo's privacy policy

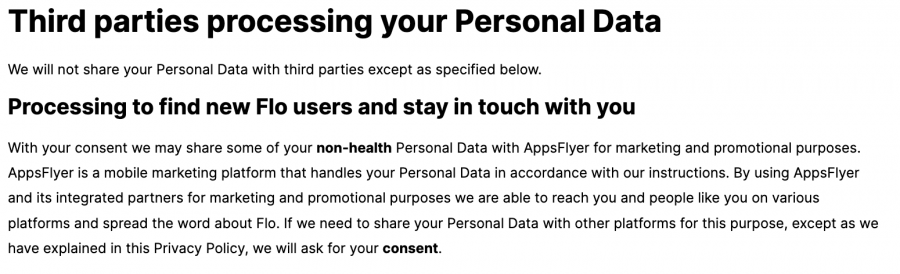

Anonymous mode

After the Roe v. Wade reversal, Flo introduced Anonymous Mode where users could input reproductive information without being tracked. It was launched to reassure users of protecting their reproductive data from law enforcement who can use it against those seeking abortion. As seen in figure 5, with the Anonymous mode they can use the app without connecting their email or other third-party data. But is it possible to create anonymous data in the heap of the digital trail that we leave? Probably not (Rocher et al. 2019). Furthermore, Flo does not have a good reputation for keeping sensitive information private.

If the surveillance economy has taught us anything, it is the fact that any data can be breached and used for incentives without our consent.

In 2021, the Federal Trade Commission called out Flo for disclosing sensitive data with Facebook and other marketing companies in a 2019 investigation, despite promising not to. The information contained sensitive data about users trying to get pregnant and their period cycles (Mozilla, 2022). There is a chance that consumers’ private information can be violated again if it has happened previously. If the surveillance economy has taught us anything, it is the fact that any data can be breached and used for incentives without our consent (Zuboff, 2019). And in a post-fall Roe v. Wade world, the state can get data on anyone who is suspected of having an abortion, quite easily.

Figure 5: Flo's Anonymous Mode

Data as currency

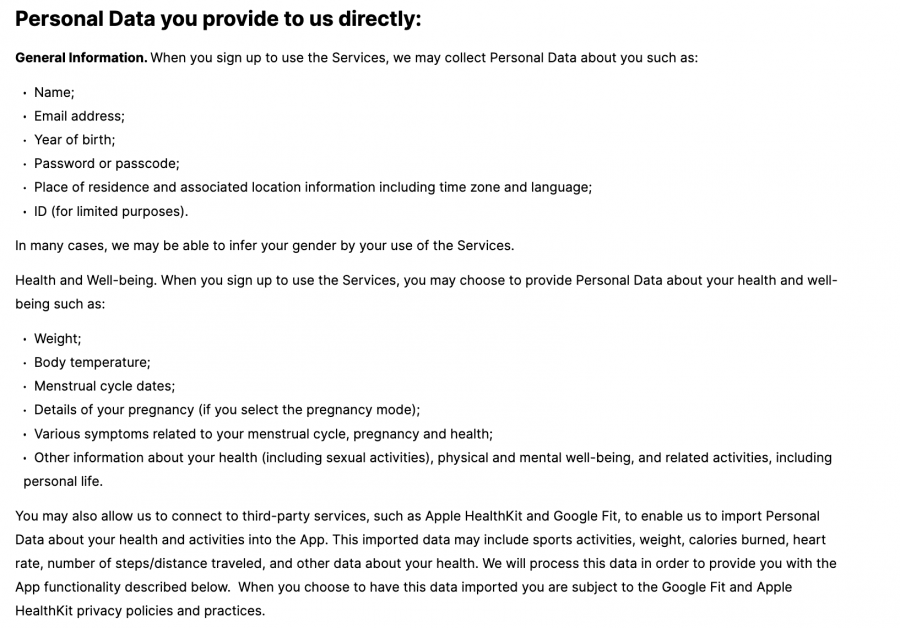

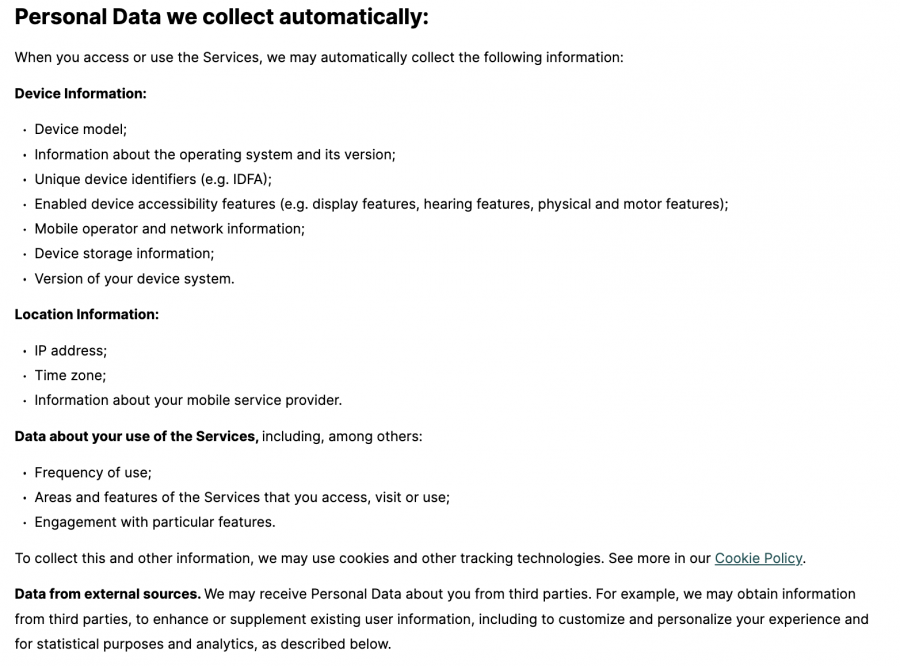

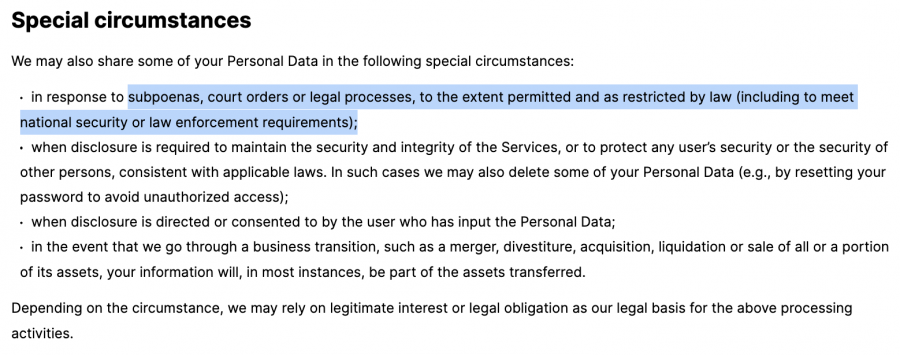

Flo’s privacy policy highlights the data users provide and the data Flo automatically collects from them (Figures 6 & 7). This data consists of basic facts about the users such as their name, email id, and even IP address. Additionally, if users want to receive more insights about their reproductive health, they can enter their weight, pregnancy details, and other health information. Flo's privacy policy also mentions (figure 7) that they collect users’ information from third parties. So that is a whole lot of data on a user who believes they have just fed in their name and email id or have willingly consented to the rest in the hope that it is kept private. This data surplus can be sold to authorities or any state that has passed a ban on abortion in the US. Shoshana Zuboff interprets this as an assault on bodily autonomy (Kavenna, 2019). Even if the individual has not uploaded any data related to their pregnancy loss, if suspected, their data could be re-identified through other multiple sources like location and gender. Fears of reproductive health data being misused or violated after the Roe v. Wade reversal are valid and should not be taken lightly. While period tracking apps assure women of transparency in their privacy policies, apps are by law obliged to share users’ data in response to subpoenas or court orders (figure 8).

Figure 6: Personal data users provide to Flo-taken from their privacy policy

Figure 7: Personal data Flo collects-taken from their privacy policy

Figure 8: Data shared under special circumstances-taken from their privacy policy

Data breaches are not uncommon, but they can have privacy implications for an individual. Users create privacy boundaries on period tracking apps by feeding selective intimate data and adjusting the level of information they disclose in exchange for support. However, abuse of such boundaries can lead to turbulence and privacy dilemmas (Petronio, 2002). Law enforcement has previously investigated crimes by tracking users' social media accounts as evidence. One such case was of a 17-year-old girl, where they used her Facebook message chat to charge her with illegal abortion (Koebler & Merlan, 2022). With the constitutional protection for the right to abortion being lifted, women in the US are fearing for their privacy as anyone can get their hands on their reproductive data, and authorities can buy it to investigate an abortion to prove the crime. The HIPAA (The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act) is a federal law that protects the privacy of personal health information in the US. However, it does not apply to the reproductive data stored on period-tracking apps. So, the power of how to utilise the information, whom to sell, or where to disclose it, lies with the companies (Spector-Bagdady & Mello, 2022). Thus, the accessibility to reproductive health data requires minimum effort, and that is a threat to human autonomy.

Delete or keep?

In conclusion, the issue of reproductive health data and its potential commodification and use against users is a persistent concern. Period tracking apps, even if they adjust their privacy policies, will always remain an unsafe space, primarily in a country with strict abortion bans. Changing the privacy policies could also be a small compliance mechanism to gain users’ trust again. In Flo’s case, they came up with an Anonymous mode to protect users’ privacy. Ideally, creating an Anonymous mode or other period apps’ efforts to protect users’ privacy should have existed from the beginning itself rather than a façade of reducing the harm they can cause.

In a world where data is easily accessible and capitalised, privacy is a myth. When users upload details about their reproductive health on period apps, they expect that data to be protected regardless. Furthermore, an individual’s digital trail can expose the most intimate details, and that data is valuable—for advertisers, marketers, and the government. While the chances of using period tracking app data in court are less, it can still be used as a shred of potentially incriminating evidence. There is no certainty that women's reproductive data may be exploited to prove an abortion in the US, however, the use of period-tracking apps have undoubtedly entered a digital dystopia.

References

A First Look at Communication Theory. (2014, January 29). Sandra Petronio on Communication Privacy Management Theory [Video]. YouTube.

Democracy Now. (2019). Age of Surveillance Capitalism: “We Thought We Were Searching Google, But Google Was Searching Us.” In YouTube.

Kavenna, J. (2019, October 29). Shoshana Zuboff: ‘Surveillance capitalism is an assault on human autonomy.’ The Guardian.

Koebler, J., & Merlan, A. (2022, August 9). This Is the Data Facebook Gave Police to Prosecute a Teenager for Abortion. Vice.

Lipka, M. (2022, June 17). Abortion views within parties: Demographic profiles of supporters, opponents | Pew Research Center.

Mozilla. (2022, August 9). *Privacy Not Included review: Flo Ovulation & Period Tracker.

Petronio, S. (2002). Boundaries of Privacy. State University of New York Press.

Privacy Policy. (n.d.). Flo.health - #1 Mobile Product For Women’s Health.

Rocher, L., Hendrickx, J. M., & De Montjoye, Y. (2019). Estimating the success of re-identifications in incomplete datasets using generative models. Nature Communications, 10(1).

Spector-Bagdady, K., & Mello, M. M. (2022). Protecting the Privacy of Reproductive Health Information After the Fall of Roe v Wade. JAMA Health Forum, 3(6), e222656.

Zuboff, S. (2019). The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power: Barack Obama's Books of 2019. United Kingdom: Profile.