Bearing witness online: How hashtags enabled an uprising in Iran

On September 13th, 2022, Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish Iranian woman was detained by Irshad patrols, also known as the ‘morality police’ in Iran, for allegedly violating the Islamic Republic’s strict dress code for women. They took her to the detention center for wearing her hijab "improperly". Three days later, she died in the hospital after falling into a coma under mysterious circumstances. Authorities claimed she got a heart attack, but witnesses say she was beaten by the morality police. Her death sparked a movement in Iran, predominantly championed by young women. Subsequently, an enormous wave of protest spread across the world, to stand against the brutality of the Islamic regime. This paper explores how Instagram became a channel for Iranian citizens to fuel the movement through hashtags and citizen witnessing. Furthermore, it will discuss in detail how the practices of bearing witness following the death of Mahsa Amini gave momentum to the ongoing uprising in Iran.

The Iranian revolt

The uprising is the latest in a series of powerful street protests in Iran that challenge the legitimacy of the Islamic regime that came to power in 1979. Since then, the Iranian security forces have opened fire on countless people and killed at least 44 children who bravely took to the streets of Iran to oppress the supreme leader's regime (Amnesty, 2022). Protests started flaring up not just on the streets but also on Instagram. Citizens took over to their accounts to report, stand up, and rage against the Islamic regime using the hashtags #MahsaAmini & #WomanLifeFreedom.

Mahsa Amini’s death gripped the world and has become a symbol for young women in Iran to fight for their rights and freedom. From chanting slogans on the ground to using hashtags to protest, citizens are leaving no stone unturned to fight for their basic rights. Weeks after the protests began, citizens have been faced with a brutal crackdown from the government leading to executions, the shooting of tear gas, and the usage of lethal force to suppress them. The protestors bear witness to the violence and keep sharing all the details on their Instagram accounts to fight back and let the world know about their oppression. They are retaliating by sharing imagery, live-streaming protests, and detailing events on their profiles.

The world has joined the movement and people are showing their support by re-sharing, commenting, and posting it on their social media feeds. The widespread protests are now picked by numerous news channels both traditional and digital. Undoubtedly, their voices have gotten stronger than any pellets or tear gas. These protests reek of fearlessness and inspiration. This movement is a perfect example of how news is not only made and shared by professionals but also ordinary people–who contribute in abundance because of their first-hand experience during a crisis. Citizens are continuously intensifying the social movement through two approaches: bearing witness and citizen witnessing.

Bearing witness & empowering through hashtags

In Iran, the traditional media is primarily controlled by the Islamic regime and counts as one of the 10 worst countries on the press freedom index (Iran, 2022). Nevertheless, when the protests began after Mahsa Amini’s death, the news started to spread like wildfire. Human rights activists, protestors, and bystanders helped in disseminating information about the brutality of the Islamic government. They took control of the crisis by bearing witness. This gave rise to a public outcry both inside and outside of the country. The concept of bearing witness refers to when citizens feel compelled to record events, frequently putting their own lives in danger (Allan, 2016). The rawness and first-hand experience of witness footage gave a sense of authenticity to the crisis. In the case of this uprising, authenticity was and continues to be important for the audience as it lends credibility to the reports and footage shared by ordinary citizens.

Following her death, citizens began painting a visual picture of the event unfolding in Iran on Instagram and started using two specific hashtags #MahsaAmini & #WomanLifeFreedom that framed the issue. "The concept of framing consistently offers a way to describe the power of a communicating text" (Entaman, 1993, p. 51). Framing is essential in human communication as it influences the reader’s thinking and helps in conveying the message. The emergence of hashtags also results in many people showing support and reusing them on their social media accounts to create awareness.

To understand how the framing of hashtags, authenticity, and bearing witness has solidified the movement, a few Instagram posts and stories will be analyzed. It is important to note that these posts represent some of the most crucial moments of the uprising.

Analyzing the uprising

For years, women in Iran have been bravely protesting compulsory hijabs offline and online. This has given them a sense of collective identity and solidarity (Khazraee & Novak, 2018). It should be considered that their solidarity has strengthened the ongoing women-led protests and given a foothold to the uprising.

Mahsa Amini’s death triggered nationwide unrest and erupted protests in multiple parts of the country. Since then, on account of its geographic territoriality, important news surrounding the vast protests is coming through ordinary people’s phone cameras. The movement has heavily relied on Instagram as bystanders keep documenting and posting about the protests. Videos continue to surface from many cities in Iran, including Mahabad, Bukan, and Piranshahr in West Azerbaijan and Javanrud in Kermanshah (Adil, 2022). Citizens, especially young women, are playing a prominent role in spearheading the movement. They are standing defiantly against the government to protest the death of Mahsa Amini and the forced use of hijab. While many women are taking a stand wearing their hijab, it is essential to remember that it is not so much about the hijab as it is about their freedom to live and have the choice to decide whether or not they want to wear a hijab.

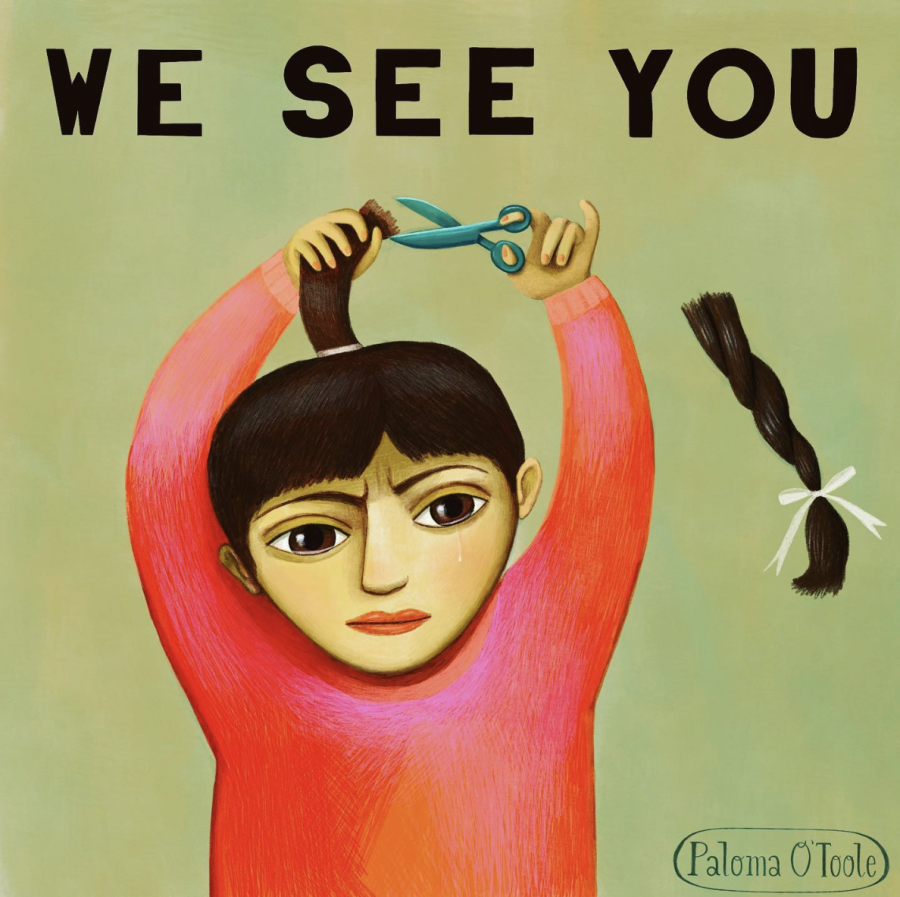

As an act of rebellion against their oppressors, they are cutting their hair, burning headscarves and going around the streets with uncovered hair.

As an act of rebellion against their oppressors, they cut their hair, burn headscarves, and go around the streets with uncovered hair. Figure 1 shows a protest where women take turns burning their mandatory headscarves and they are chanting “no to the headscarf, no to the turban, yes to freedom and equality”. The video was recorded from a phone camera and enables viewers to process the experience in all its novelty. While it is not a professional high-quality video, it gives citizens the power to capture the moment on the spot and publish it instantly (Allan, 2016). This footage, therefore, represents authenticity and rawness for the viewers who are witnessing the crisis audio-visually through the media.

Figure 1. Women taking part in protests by burning their headscarves

The protests started to grow rapidly as more videos began to circulate. Women burning their headscarves and cutting their hair online to abolish the Islamic regime caught everyone’s attention. What started as a protest of slashing their hair, has now become an important aspect of the uprising. The compilation below (Figures 2 & 3) shows women cutting their hair on cameras. This act is one of the most meaningful forms of rebellion against the oppressors. In the Islamic Republic, hair is a sign of beauty for Iranian women and therefore must be hidden under the hijab. Chopping off one’s hair is thus a symbol of mourning and support for every Mahsa Amini and all the victims who suffered from the brutality of the regime. It has led to collective empathy and triggered anger towards the regime, with many women from outside of Iran showing their solidarity by cutting their hair on other social media platforms. Celebrities and politicians are also showing their support by doing the same. Witnessing such photos and videos has given people an authentic look into the event and increased their emotional affectivity. When people witness this event through the media, it does not directly affect their lives but has an emotional impact on them due to their portrayal and viewers’ subsequent witness to them (Allan, 2016).

Figure 2. A woman cuts her hair in solidarity with Iranian women

Figure 3. Women chop off their hair to stand against the oppressor

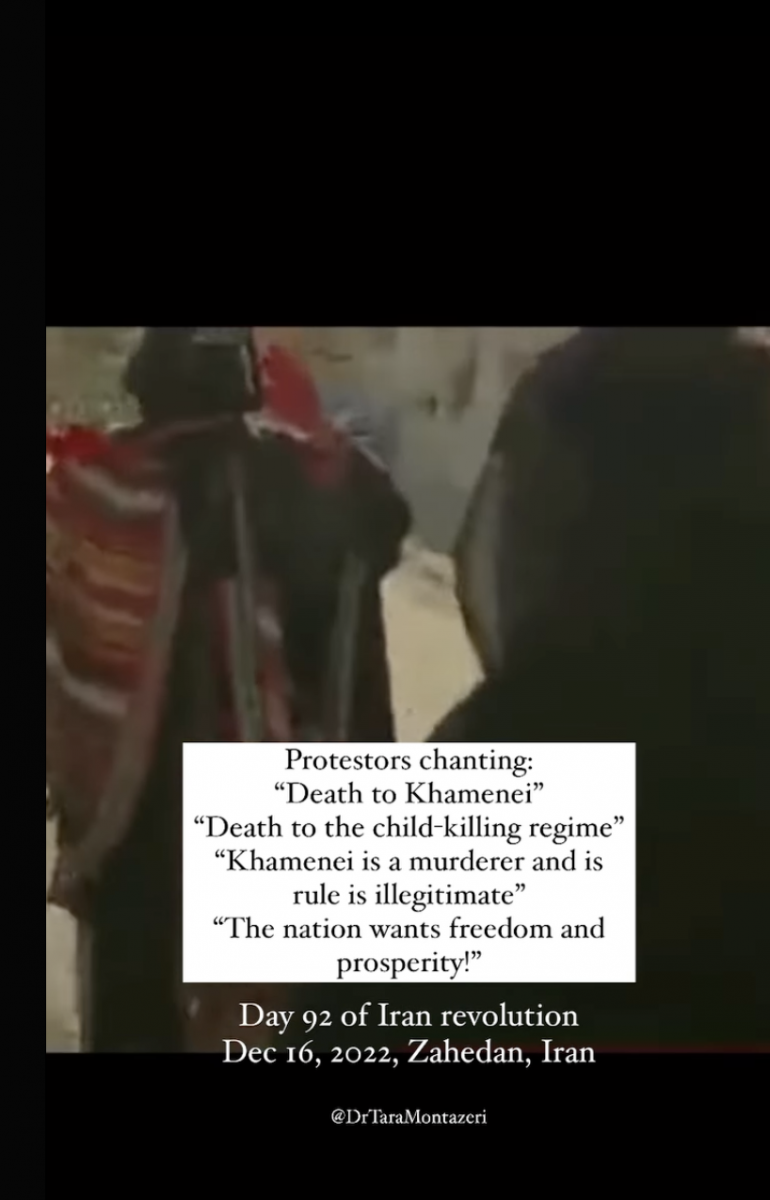

The video in Figure 4 shows protestors chanting “Azaadi”, which means freedom, and circling around burned headscarves. While figure 5 shows citizens shouting “death to the dictator”. These rallying cries have been a crucial part of the protest throughout. These are a few of the several protest videos on Instagram that are helping fill the news vacuum during a crisis. Citizens feel it is their moral duty to get the message across despite a huge personal risk from the external forces of the government. The first-hand documentation of the ongoing protests further enables people who are not present to effectively understand the intensity of the crisis. The viewers along with the protestors are accomplices in the crisis because they are seeing what happens when it transpires. More importantly, people may watch those videos from another time or from a different country, but the event displayed makes a silent appeal to their conscience to not pretend as though they are unaware of the crisis (Allan, 2016).

Figure 4. protestors chant ‘Azaadi’

Figure 5. citizens shouting death to the dictator

#MahsaAmini and #WomanLifeFreedom have been consistent and relevant hashtags for everyone to follow the crisis. They have been the backbone of the movement. As the news of Mahsa Amini’s death broke out, hashtags have been an effective form of spreading information and protesting against the regime. They are now used for creating conversations, re-posts, and discussions from people worldwide on other social media platforms such as Twitter, Facebook, and even TikTok. People are now populating hashtags to show their support and voice their opinions in this mass movement. The way these hashtags are framed highlights information about the current crisis making it more salient (Entman, 1993). #MahsaAmini and #WomanLifeFreedom have substantially helped gain visibility about the current situation in Iran by enabling users to discover the accounts of key information sources on the hashtag event.

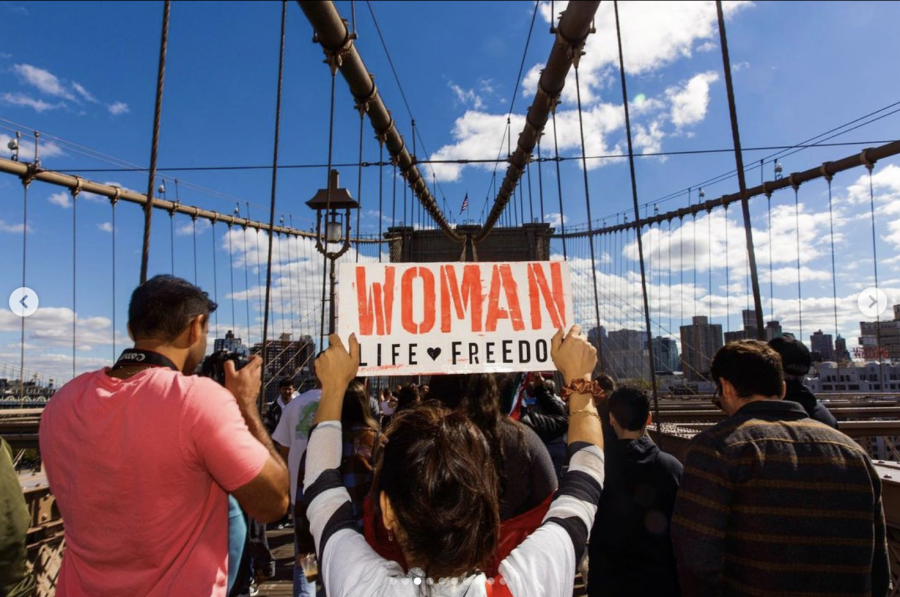

Instagram, a visually loaded social platform, now has countless posts under these hashtags. They were worded by the citizens to convey what women in Iran are fighting for. The selection of words used in the hashtags defines the movement. Framing of the hashtags is essential as it “exercises a certain interpretive power over what is unfolding" (Bruns, 2018, p. 81). With #MahsaAmini, people want Mahsa Amini to be remembered and create awareness about the plight women are going through in Iran. It is not just a name but a telling attempt to defy the oppressors and let the world know of the unrest. #WomanLifeFreedom is a literal translation of a Kurdish slogan coined by Kurdish female fighters, “Jin (woman) - Jiyan (Life) - Azadi (Freedom)”. It has become a poignant cry in response to Mahsa Amini’s death. The hashtag echoes what Iranian women have been bravely fighting for–their fundamental rights and freedom (figure 6). Citizens are using both hashtags with audio-visual material to shed light on the crisis in Iran and get their voices heard. Furthermore, people around the world are taking part in the protests with these hashtags to bring awareness. Evidently, the initial coverage of news began with the bystanders on Instagram rather than news networks. As more videos and photos began circulating, news channels quickly picked up the news and started covering the protests by including footage from ordinary citizens (see Figures 7 & 8).

#WomanLifeFreedom echoes what Iranian women have been bravely fighting for–their fundamental rights and freedom

Figure 6. a protestor holding the #WomanLifeFreedom sign

Figure 7. news channel showing footage captured by ordinary citizens

Figure 8. news channel showing footage captured by ordinary citizens

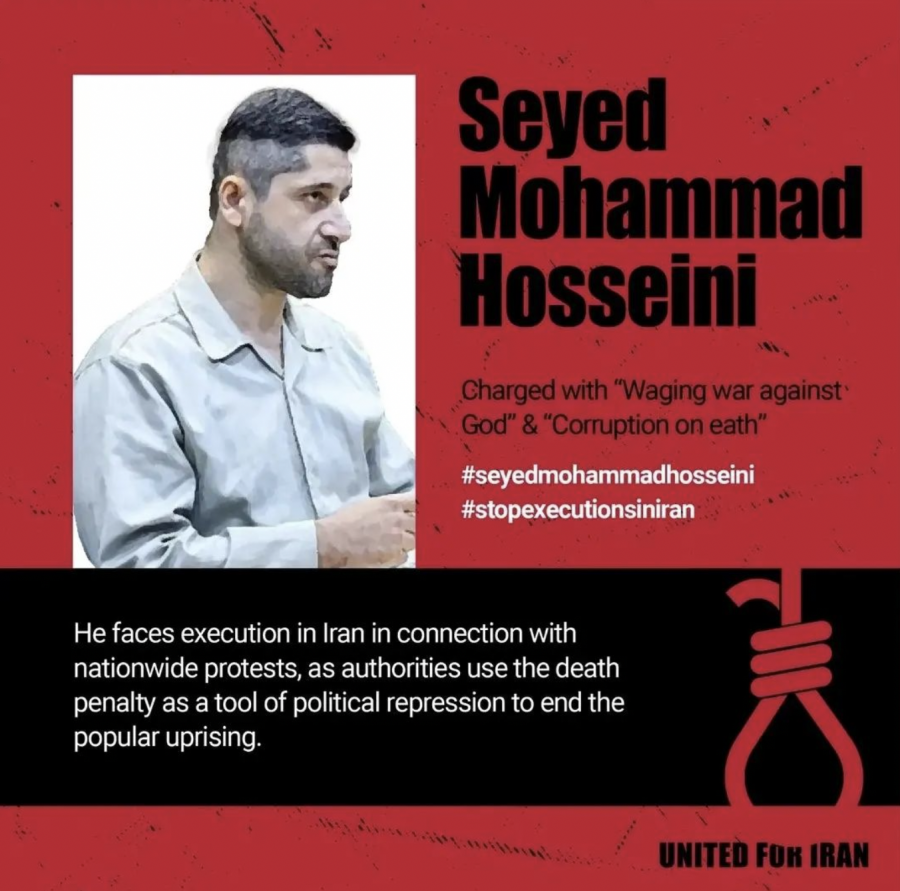

Hashtags enhance the accessibility and dissemination of critical information about an event, encouraging distant social media users to participate (Bruns, 2018). As a result, both hashtags have more than a million posts on Instagram with a broad range of actors all around the globe. However, many posts within these hashtags are not news about the protests. They come from a myriad of emotions–condolence posts, art dedications (Figure 9), petitions to stop executions (Figure 10), and conversations about the movement. Such type of content is contributed by the ad hoc public. Ad hoc public refers to a group of people who come to the hashtag only after the event has happened, engage and dissolve again (Bruns, 2018).

As the protests continue to gain more power, Iran has restricted access to WhatsApp and Instagram in certain areas to repress the demonstrations (Strzyżyńska, 2022). Nevertheless, citizens across the country, human rights activists, and people outside of Iran are posting updates and leading the protests. The news coverage of this crisis, therefore, has become a hybrid form of coverage with first-hand witnesses, witnesses through the media, professional journalists, and official news channels disseminating information and strengthening the movement.

Figure 9. art dedication by an artist

Figure 10. petition to stop the execution of a protestor

All or Nothing

In Iran, citizens are providing the latest developments of the protests through their Instagram posts and helping the uninformed get a grasp of what is happening during the crisis event. Bearing witness to the crisis has put considerable power in the hands of the powerless, giving them a voice and a platform to challenge their clerical leaders. Due to its enormous visibility, the movement has grown manifold. One of the main aspects of bearing witness in these protests is that citizens are ensuring they are seen and heard, even when one scrolls past it on their social media. Their voices have been amplified to a point where people can no longer turn a blind eye to the crisis. The stories, videos, and posts are a constant reminder for the rest of the world to not look away from the revolt and the wrongdoings of the regime. The movement has significantly gained momentum through the fearless citizens who bear witness to the crisis every single day. The price they are paying for their freedom is horrific, with 475 civilians killed and 18,000 detained and counting.

And yet, they rise.

References

Adil, H. (2022, November 21). ‘Say her name, Mahsa Amini’: Iran protests arrive at World Cup. Qatar World Cup 2022 News | Al Jazeera.

Allan, S. (2016). Citizen Witnesses. The SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism (pp. 266–279). SAGE Publications Ltd.

Amnesty International. (2022, December 11). Iran: Killings of children during youthful anti-establishment protests. Amnesty International.

Bruns. A. (2018). Gatewatching and news curation: journalism, social media, and the public sphere. Peter Lang.

CNN. (@cnn). (2022). The death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini. [Video] Instagram.

Entman, R. M. (1993). Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication, 43(4), 51–58.

FJParsa. (@farhadjphotographs). (2022). If your religion, the blood of lovers demands. [Photograph] Instagram.

FJParsa. (@farhadjphotographs). (2022). I hope the blood will feed the roots we have for a better future. [Photograph] Instagram.

Guardian. (@guardian). (2022.). They do not want us to call it protests anymore. [Video] Instagram.

Iran. (2022, November 9). RSF.

Khazraee, E., & Novak, A. N. (2018). Digitally Mediated Protest: Social Media Affordances for Collective Identity Construction. Social Media + Society, 4(1).

Liberatum. (@liberatum). (2022). Iranian women we are with you. [Photograph] Instagram.

Lost in history. (@lostinhistorypics). (2022). Mahsa Amini has become the name of REVOLUTION in Iran. [Photograph] Instagram.

Montazeri , T. (@drtaramontazeri). (2022). The brave people of Zahedan protesting for a free Iran. [Video] Instagram.

O’Toole, P. (@palomaotoole). (2022). Women of Iran are still protesting and demonstrating. [Photograph] Instagram.

Shaghayegh. (@shaghayeghdarabi.art). (2022). Now that they put their hands in front of your mouth, I will be your voice. [Photograph] Instagram.

Strzyżyńska, W. (2022, October 19). Iran blocks capital’s internet access as Amini protests grow. The Guardian.

افشون. (@afshoon). (2022). Tonight an Iran is out. [Video] Instagram.