How China’s #MeToo evaded the “great firewall” in the digital world

With a draconian online surveillance system in place, China’s censorship is tough to evade. So, how did a movement like #MeToo mobilize under the eyes of the big brother in China?

China’s rigid censorship, also known as the “Great Firewall” is an expansive set of legal and technological measures that shields Chinese citizens from unwelcome content. The authorities use this to filter, ban, and block content and monitor their citizens. It is no surprise that China’s online patrolling system is advanced and that it blocks not just foreign websites, but also any use of keywords that are objectionable under their guidelines. However, amid highly controlled and authoritarian censorship, China’s #MeToo movement managed to make a place for itself in the digital world successfully, albeit creatively. By using Doug Belshaw's concept of digital literacies, this paper will analyze how Chinese activists navigated the digital sphere and bypassed China's great firewall. It will examine the ways and methods Chinese activists used to put the #MeToo movement on the digital map despite extensive surveillance from the authorities.

#MeToo in China

Tarana Burke coined the phrase “me too” in 2006 to stand in solidarity with the survivors of sexual harassment and assault. A decade later, in October 2017, it turned into a viral hashtag in the US as survivors of sexual assault came forward and accused Harvey Weinstein. Since then, #MeToo unleashed multiple sexual harassment accusations against several ordinary and prominent figures across the globe and brought to light the discourse about rape culture and undetected sexual abuse. #MeToo movement became a voice for people to talk about their unsettling experiences.

The movement got a global take-off but was still in its nascent stages in China. For China, the movement garnered public interest on the 1st of January 2018, when a former university student from Beihang University made a sexual assault allegation against a professor. She posted her ordeal in an open letter on Weibo, China’s largest social media platform. Her post attracted around 4 million views and 16,000 shares by the next day (Abbott, 2019). Following her post, many Chinese women started speaking up against their harassers and spreading public awareness of sexual harassment. They began using #MeToo and #WoYeShi which is the Chinese translation of #MeToo, on several other online platforms like Weibo and WeChat, to name a few. Chinese online platforms were flooded with these hashtags and the discourse surrounding sexual harassment. A few days into the movement, authorities started blocking those hashtags, deleting relevant posts across all social media platforms and any content related to #MeToo in order to avoid any more public discussion. That is where the challenge began for Chinese activists. To evade censorship, they started speaking up against their assaulters in the most strategic and creative way. Since authorities had banned any keywords related to #MeToo or its Chinese translation, the activists came up with their own version of #MeToo to bypass censors and avoid the risk of being flagged.

To create meaningful dialogues around #MeToo, activists used more than just their basic digital skills. Using visuals, signs, symbols, and playful manipulation of old hashtags, they used digital literacies to evade the censors and keep the movement going.

Doug Belshaw describes digital literacies as the capability to go beyond basic digital skills to create and communicate rather than simply use digital tools. In digital literacies, the process of meaning-making relies heavily on context (Belshaw, 2014). Therefore, digital literacies involve learning and using knowledge, aptitudes, and certain skills to talk about important issues in a digital space.

From #MeToo to #mǐtù: The Battle of Wits

China spends an extensive amount of money on advanced technologies to censor important topics that cannot be openly discussed or called out (Fedasiuk, 2021). Evidently, after the ban and searches of most of the #MeToo content, China’s activists started bypassing the censorship by using a hashtag that sounded like “me too”. They began using #mǐtù (#米兔) which is a homophone for #MeToo as shown in Figure 1. In Mandarin, mǐ (米) means rice, and tù (兔) means bunny, which translates to rice bunny. Soon that was blocked by the authorities. To trick the censors and algorithms, Chinese activists started creating other variations of #mǐtù, such as emojis of a rice bowl and a bunny together (Yang, 2019). This became a clever way to evade the censors without being banned or flagged. Illustrations or emojis are not easily detected by automatic censors and need to be manually censored. The emojis of a rice bowl and a bunny and the hashtag, therefore, became a sign of defiance for the Chinese women. The use of these symbols and hashtags wasn’t just a creative way, but a calculated retort to circumvent the censorship.

figure 1: homophone for the word #MeToo

Hashtag has been a binding force in digital activism for years. It is no longer just a mere symbol on the keyboard. Users have utilized it beyond its factual consumption and turned it into a useful key that can lead social movements and encourage public participation. It gives a sense of solidarity while emphasizing how experiences are shared within a community. The use of hashtags is one of the several ways in which Chinese activists remixed different digital literacies to create and engage in constructive dialogues. They used their knowledge of digital skills to understand how to navigate censorship. By using variations of the hashtag and homophones, they camouflaged #MeToo by remixing different literacies. Since authorities block keywords frequently, activists also started using linguistic puns and misspellings and turned banned keywords into homophones to outrun the censors. Even after #mǐtù was blocked, they created hashtags out of local dialects to keep the movement going — for instance, #俺也一样 (or me, it’s the same) and 子也是 (I also am) (Guttenberg, 2021). Despite the censorship, Chinese activists found innovative ways to perform effective digital actions.

China’s advanced filtering technologies may not be beneficial to the activists, but it has also given rise to radicals who have figured out a way to navigate the mediascape in China. When a popular and prominent CCTV host Zhu Jun was accused of sexual harassment, due to his connections with the Chinese authorities, the use of his name on any platform was censored. Activists, therefore, started using a homophone for his name — zhūjūn (which means Swine bacteria, 猪菌). This is a perfect example of how they created new meanings by recycling, modifying the old text, and remixing hashtags to evade the censors.

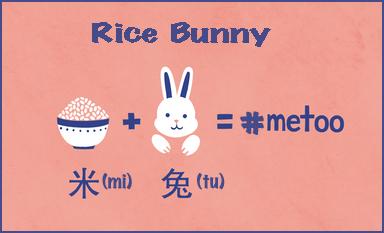

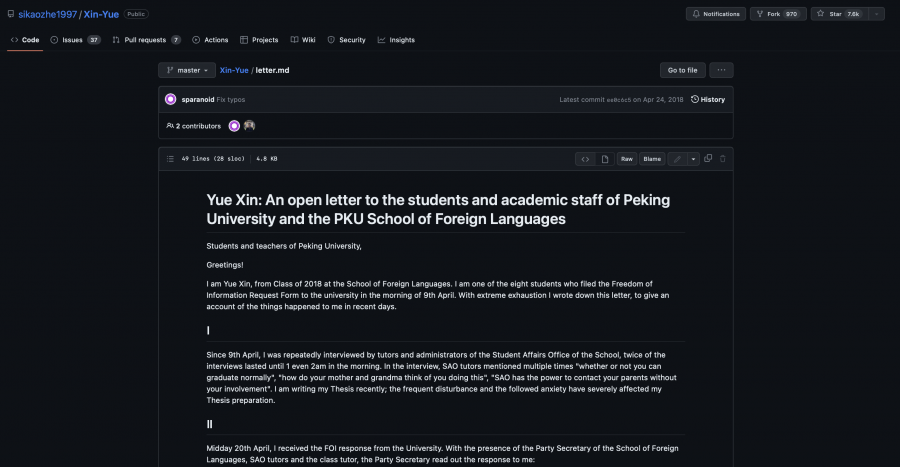

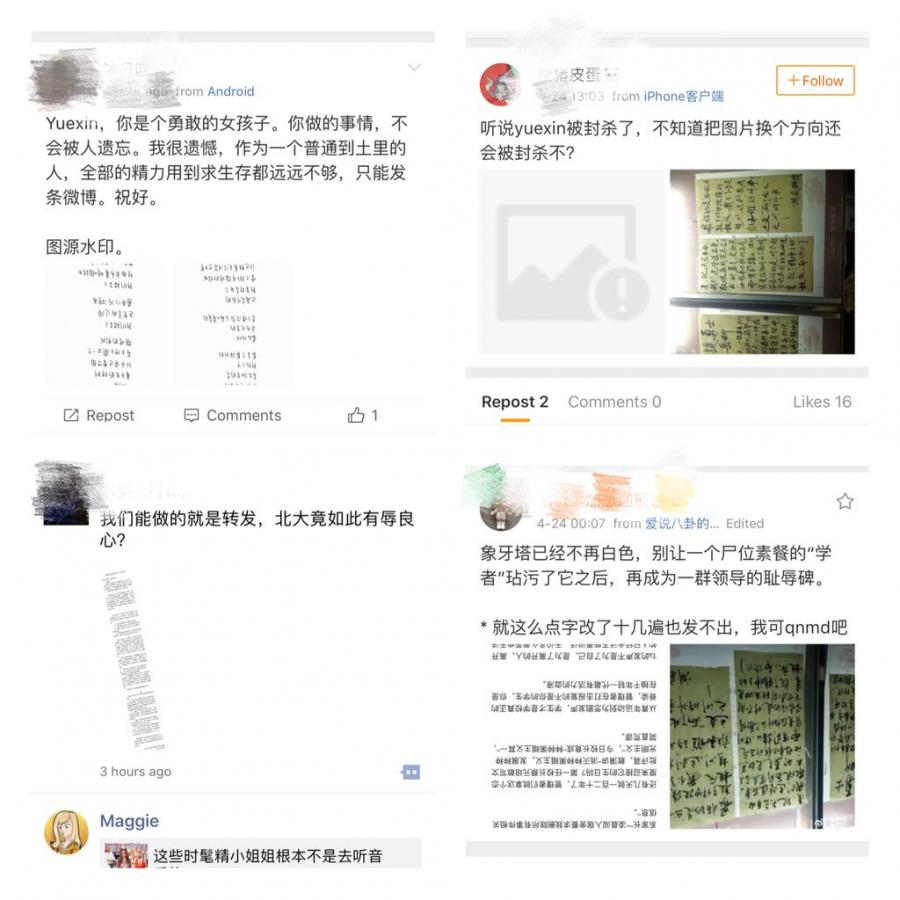

As the #MeToo movement started gaining more visibility in China, Peking University (PKU) students issued a petition requesting that university administrators act in the wake of the movement by reopening a 1998 sexual harassment case. The case involved a student named Gao Yan who killed herself after accusing her professor, Shen Yang, of sexual assault (Hernández, 2021). After PKU rejected the petition, Yue Xin, one of the petitioners, posted an open letter on WeChat narrating her experience and battle against the university officials. Her letter was shared immediately on multiple Chinese social media platforms before it was permanently removed from every platform. To outsmart the authorities, Yue’s ally employed a creative method of caching—which refers to the process of storing sensitive content away from the censors (Zeng, 2020). The supporter made a transaction on the cryptocurrency Ether, intentionally leaving it empty and attaching Yue's letter to the transaction record as shown in figure 2, therefore making sure that it is stored on the internet permanently. Similarly, Chinese activists uploaded the letter to GitHub, a well-known coding website, making it accessible for anyone to view ( see figure 3) (Zeng, 2019). Another example of their excellent evasion technique is the way activists used rotated images to evade the censors. Since images are also subject to censorship, activists discovered a means to get around the image identification algorithms, making it difficult for the government to enforce its censorship policies. They uploaded rotated images on Weibo and WeChat as seen in Figure 4, which consisted of Yue's letter.

figure 3: Yue's letter on Github

figure 4: rotated images of Yue's letter to resist censorship

Belshaw mentions how the practices of digital literacies keep evolving. Therefore, it is critical to understand the nature of the constant shift and act in accordance with it. Publishing Yue's letter strategically on platforms that could not be censored shows how the activists adapted quickly to the changing environment around them and remixed things to make an impact.

The activists, therefore, utilized their literacy skills to the fullest and moved beyond the elegant consumption of literacy. According to Belshaw, elegant consumption of literacy is a linear way of maneuvering technology. In the above scenarios, however, Chinese activists went beyond the elegant consumption of literacy. They participated, collaborated, and shared content by creating and using their digital skills effectively and efficiently.

The Verdict

As the censorship gets more stringent by the day to ensure harsher control on online platforms, activists work harder to go beyond the censors’ filtering techniques. From coming up with innovative tactics to skilfully amplifying the victims’ voices, Chinese activists have facilitated meaningful discussions in the #MeToo movement. Their efforts led to a landmark case of #MeToo that was brought by Zhou Xiaoxuan against one of the country’s most famous star TV hosts Zhu Jun. However, Zhou Xiaoxuan lost the case which could have been the country’s first sexual assault case ever won at that time.

Chinese activists used their tools actively to call for social action. Calling for a systemic change in one of the most authoritarian countries is no mean feat. In a country that did not have any clear legal definition of sexual harassment, the evasion strategies used by Chinese #MeToo activists prompted the government to incorporate for the first time a civil code of law, Article 1010, that defines what constitutes sexual harassment and allows people to file a lawsuit under sexual harassment. The civil code also requires employers and schools to take preventative measures and address sexual abuse. The implementation of the civil code is a small step towards change but a big win for Chinese activists. While the authorities have blocked #MeToo on Chinese social media platforms, the campaign still lives on in creative ways. By using their digital literacy skills to their best knowledge and sometimes even going above and beyond, Chinese activists remain resilient in the face of authoritarian censorship, to date.

References

Abbott, J.P. (2019), Of Grass Mud Horses and Rice Bunnies: Chinese Internet Users Challenge Beijing’s Censorship and Internet Controls. Asian Politics & Policy, 11: 162-168.

Belshaw, D. (2014). The essential elements of digital literacies.

Fedasiuk, R. (2021, January 12). Buying Silence: The Price of Internet Censorship in China. Jamestown.

Guttenberg, V. (2021). Rice Bunnies vs. the River Crab: China’s Feminists, #MeToo, and Networked Authoritarianism. Flux, 11(1), 31-39.

https://doi.org/10.26443/firr.v11i1.59

Hernández, J. C. (2021, March 29). China’s #MeToo: How a 20-Year-Old Rape Case Became a Rallying Cry. The New York Times.

Yang, Y. (2019, August 9). China’s ‘MeToo’ movement evades censors with #RiceBunny.

Zeng, J. (2019). “You Say #MeToo, I Say #MiTu: China’s Online Campaigns Against Sexual Abuse.” In #MeToo and the Politics of Social Change, edited by B. Fileborn and R. Loney-Howes, 71–83. Palgrave MacMillan.

Zeng, J. (2020). #MeToo as Connective Action: A Study of the Anti-Sexual Violence and Anti-Sexual Harassment Campaign on Chinese Social Media in 2018, Journalism Practice, 14:2, 171-190.