Digital economy and platform ideologies

Economy and ideology. Combine the terms and one immediately thinks of Marxism. As is commonly known, in the Marxist theoretical tradition, ideology is part of superstructure; while ‘the economy’ makes up the base of society. In its classic Marxist formulation, it is the base — that is the relations of production and the forces of production — that in last instance determines the ideas. Or more concretely, it is the ideology of the ruling class — that is the class that controls the social surplus product and thus has economic hegemony — that succeeds in normalizing their ideology. This ideology will dominate state discourses, will manifest itself in the law, the norms and values that people embrace, in religion, but also in science, art and literature: ergo, it will dominate superstructure. While this relation between base and superstructure is seen by many critics as too economically deterministic, the actual (or at least parts of that) Marxist tradition is less mechanical than its opponents like to assume. The underlying assumption of this relation between base and superstructure is that people are social and discursive creatures. In the words of Mandel, this means that ‘everything humans do or produce, must “go through their heads” and is therefore accompanied by “ideological” representations (in the guise of ideas, systems of ideas, hopes, fears and other feelings) which react in turn on the material actions of those who experience them” (Mandel, 1994). Ideas, it is thought, exist or come into existence in a relation to the material world: people live their lives in certain labor and social circumstances, and this material reality influences how they think. But ideas are not mere byproducts. To a certain degree, ideas can influence how we see reality. If we understand work as empowerment or exploitation, it doesn’t change the work itself, but it does change how we feel about it. This is where ideology comes in. How we see and frame the world impacts the structure of the world. If the powerful — usually under pressure of popular resistance — conclude that slavery is unethical, or the climate crisis a real problem, then policies can be put in effect to change these realities. There is thus a dialectical relation between base and superstructure and discourse plays a crucial role in that relation.

A research focus on the relation between the base and superstructure, especially in the context of digital economy and digital culture, is still productive today. Precondition: avoid a mechanic or monolithic view on this relation. Any a priori theorization will eventually derail. But base and superstructure are useful and productive as sensitizing concepts (van den Hoonaard, 1997; Maly, 2022) in a digital ethnographic approach. In the remainder of this article I want to show how those concepts can be utilized to make sense of the ideological role of digital platforms in contemporary societies. The reader will forgive me for the many detours, but I do hope that the exercise ahead can be useful to eventually analyze the ideological power of digital media platforms in general, and social media platforms in particular.

Researching ideologies and digital platforms

In a hyper-mediatized society (but even in the days of Marx), it is obvious that the notion that there is a dominant ideology, doesn’t mean that there is only one ideology. The ideological impact of the base should not be understood as if there is a one-on-one relation between economy and ideology. On the contrary, ideologies are part of the power struggles between different groups in a society. In the end, ideology is the work of actual people, with actual interests, class positions, social relations and cultural practices that all influence the shape, content and distribution of ideas. Ideas exist in real contexts of (ideological) power struggle. The economy – if we adopt an ethnographic perspective – is shaped by people who live and work in specific material contexts, and thus in specific relations to each other and to the economic system in general. They have access to certain media and not others, meet certain people and not others. This is how the material realities (of firms and platforms, societal institutions and companies) help to shape the ideas of certain groups of people. If you work in a hip Sillicon Valley work place, where you can enjoy a good wage, hip infrastructure and all kind of benefits, you might think differently about that place, than when you work for that same multinational in a poorly paid moderation function. Important, even though these material circumstances probably have a huge effect, they do not determine them. You can be a well-paid socialist in the heart of Sillicon Valley. History has proven that shitty labour situations do not necessarily produce socialists, more is needed to question the dominant ideas that structure the economy (see Chun, 2018).

How does this now help in analyzing the ideological impact of digital platforms? First take-away is that digital platforms are part of the base of society. We can discuss to what extent they are capitalist forces of production (or merely rentiers); they clearly organize specific relations of production. In other words, they form the foundation of many suprastructural phenomena (see for instance, Miller, 2011: 7). In other words, digital platforms influence social, economic and political life and it is this concrete life in relation to infrastructures and social and economic relations that gives birth to specific social consciousness. It is thus not ‘the digital economy’ or ‘the class’ in abstracto that shapes consciousness, but the actual lived reality with its specific relations of production, socio-cultural life and access (or non-access) to certain resources, domains, institutions and all sorts of capital, that shapes which ideas circulate and eventually dominate and which won’t. Digital platforms, considering their omnipresence, have a huge impact on the establishment of those relations.

Digital media are not just powerful mediators of discourse, they ‘govern’ the interaction possibilities, and they do this from a position of power

Thus, while it is indisputably true that ideologies cannot be dissociated from their material foundations, it is — in the contemporary context of late capitalism and hypermediatization — analytically important to avoid excessive economic determinism. Or to rephrase this: it is key to avoid generic a priori assumptions, and to actually analyze how people develop ideas in relation to material (economic and technological) contexts. Contemporary reality forces us to analyze the actual emerging ideologies in two particular ways:

First we need to take the notion on board that ideologies are relational and discursive phenomena: they are related to the actual ways in which people create their worldview as a social group vis a vis other social groups. As already stressed, they never do this in a vacuum, but always in very concrete material and sociocultural contexts. In the last five decades, those contexts have changed fundamentally. High mobility, globalization of the economy and digitalization have reshaped the world profoundly. As a result, context cannot be a priori limited to a national or regional context anymore (Blommaert 2010; Maly, 2023). The actual discursive production of human beings takes place in layered, stratified, polycentric and transnational contexts (Blommaert, 2005, 2010; Maly, & Varis, 2015) that are of course still shaped by specific power relations. In practice this means that ideologies exist as very specific mixtures, assemblages or synchronizations of different ideas and ideologies. This last point is not new; the dominant ideology was always ‘a realm of contestation and negotiation, in which there is a constant busy traffic: meanings and values are stolen, transformed, appropriated across the frontiers of different classes and groups, surrendered, repossessed, reinflected’ (Eagleton, 1990: 101). This notion of ideology as a site of contestation and negotiation explains why some workers believe that capitalism works for them, even though objectively they themselves were never able to reap the fruits of that seemingly benevolent system (Chun, 2018). It also explains how democratic socialist parties can incorporate all kinds of liberal, neoliberal and even anti-socialist discourse (Maly, 2021). The net result, is a different dominant ideology.

Ideologies are historical and social constructs. In contemporary societies, this also means that ideologies are mediated. Throughout the twentieth century media have become one of the dominant sites for the production, reproduction and consumption of ideology (Thompson, 1990; Maly, 2020). It is well documented by now that, with the rise of digital media, the 20th century media landscape has changed fundamentally once again (Chadwick, 2017). Seen from a positive or empowering perspective, in theory, the new media landscape has enabled all of us with the potential to articulate and amplify our voices. In practice, we see that digital media haven’t created a level playing field. Far from it. Some people have huge reach, while others are almost completely invisible.

From a negative perspective, we could argue that it is — especially in digitally advanced societies — almost impossible to live an unmediatized life, or broader, a life outside of platforms. The digital economy is maybe one of the dominant contexts in which we construct ideology nowadays. And this context is highly unequal: some have vastly more power to shape and make one ideology dominant: platforms have more power than individual users, and influencers with millions of followers more than individuals with 500 friends. Even though users have agency, and can choose for alternatives (Burgress, Albury, McCosker & Wilken, 2022) it is also clear that massive mainstream platforms for instance have unprecedented power over the people that use them.

The dominance of those platforms in social life raises many questions in relation to the production and circulation of ideology. How does ideology take shape in that changing landscape? What are the effects of not being on platforms, or being unsuccessful and thus invisible on those platforms for the circulation, but also consumption of ideology? Who succeeds in becoming visible on those platforms and dominating the superstructure, and what is to be done to succeed in this ‘Big Tech’ controlled environment? But also, which social media platforms succeed in dominating the public sphere? And what does this new media environment tell us about the relation between base and superstructure? Or more concretely, if we see (digital) media as crucial infrastructures for the production and circulation of ideology, which ideologies dominate in that system and, crucially, what is the ideological role of those infrastructures in the selection of discourses that are granted visibility (Bucher, 2018) and the ones that are pushed into a black hole? The digital economy, especially when we look at social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Weibo, Instagram and the likes, are not just economic in nature, they are also cultural and thus ideological. This is true, not only for social media platforms, but also for commercial platforms like Amazon, AliExpress (see for instance Keane & Yu, 2019), AirBnB, Uber and Spotify. They all facilitate the commodification and purchase of cultural products, and in that sense normalize certain cultural values and perspectives.

The digital economy, ideology and the programming of social relations

Let’s break this down further by zooming in on ‘the base’. Doing that means that we cannot ignore that digital media companies are increasingly dominating ‘the economy’. Twenty-one of the largest 100 transnational corporations are active in media, communication and the digital industry (Fuchs, 2021). In 2009, digital platforms made up only 16% of the top 20 companies by market capitalization, in 2018 this number surged to 56% (Sadowski, 2020). A tiny number of platform companies has succeeded in dominating not only global communication flows, but the economy in general. In less than two decades, five American companies — the so-called 'Big Five’ (Alphabet (Google), Amazon, Apple, Meta (Facebook), and Microsoft) and a handful of Chinese players (Tencent, Alibaba, Baidu and JD.com) — are dividing the digital political-ideological pie (van Dijck, Poell & De Waal, 2018:26).

The rise of the digital platform entails not just the rise of a new technology, or a new industry: more and more scholars see this rise in more profound terms. The impact of platforms on the relations of production touches upon a hot debate among economists, social scientists, and culture studies and communication scholars. On the one hand, they understand digital platforms as part of capitalist economy. This 'digital capitalism’, as Fuchs sees it, ‘is not a new phase of capitalist development, but rather a dimension of the organization of capitalism that is shaped by digital mediation’ (Fuchs, 2021: 2). What is new about digital capitalism, according to Fuchs, is that central capitalist processes (like the accumulation of capital, but also class struggle) are now mediated by digital technologies, digital information and digital communication. Störm (2022), like Srnicek (2018), sees digitalization as an extra layer that is added to capitalist production processes, realizing further abstraction. The result, according to him is a new type of capitalism that is caused by the fusion of cybernetics and capitalism. Srnicek sees the digital platform as a new type of capitalist firm. Key to this new type of firm is the process of extracting and controlling of data. Platform ownership is then the ownership of hardware and software that enables the extraction of data (Srnicek, 2018). Surplus, to echo Marxist discourse, is not so much extracted from labor in its traditional meaning, but from interaction. In this sense, digitalization expands the economic field into our private lives, and takes value from the production process of traditional capitalist (and non-capitalist) organizations. Our communications, the performances of who we are, but also of what we do, are now surveilled, datafied, remodeled and commodified. Zuboff (2019: 13) sees this as ‘a new logic of accumulation’ that creates ‘a new actor in history’. She, by now famously, coined this new phase of capitalism ‘surveillance capitalism’. ‘It is of its own kind and unlike anything else’, she says and ‘in the business of aggressive extraction operations that mine the intimate depths of everyday life’ (Zuboff, 2019: 19). Surveillance capitalism creates ‘behavioral surplus’ by harvesting ‘behavioral data’ using machine intelligence or as Zuboff calls it ‘new means of production’ to create predictive models that can be sold to advertisers’ (Zuboff, 2019: 93-95).

Other authors increasingly suggest that the digital economy is not just a new phase in or of capitalism. Varoufakis (2021), Durand (2022) and others argue that the contemporary digital economy is emblematic of an entirely new emerging economic system. They discuss the digital economy in terms of a new form of feudalism: ‘techno-feudalism’. At the heart of this thesis is the observation that ‘today, the global economy is powered by the constant generation of central bank money, not by private profit. Meanwhile, value extraction has increasingly shifted away from markets and onto digital platforms, like Facebook and Amazon, which no longer operate like oligopolistic firms, but rather like private fiefdoms or estates.’ (Varoufakis, 2021). Durand, who subscribes to the techno-feudalist hypothesis, argues that Big Tech does not make profit from the quantity of products sold, ‘but in the social space under the firm’s control’ (Durand, 2022: 37). Sadowski (2020) agrees with the analysis that we should see digital platforms as rentiers who ‘capture revenue from the use of digital platforms (…) they are the gatekeepers to the internet and owners of software applications.’ (Sadowski, 2020). While some see this rentiership as a new phase of capitalism, others like Sadowski see it as part of capitalism. Rentiers control and own the access to a condition of production, and in that sense, even though they don’t create new wealth, but redistribute wealth, they play a central role in capitalist production. Morozov, who first in 2016, saw the internet’s economy as a system of neo-feudalismn (Morozov, 2016, has in 2022 stressed that he sees those re-feudalizations caused by digital platforms as part of neoliberal capitalism (Morozov, 2022).

No matter if we now see this digital rentier economy of platforms as part of capitalism, or as a new phase, what is clear is that as a result of this rentier function and the mediatization and datafication of social live, there are new relations of production ‘whose rapid spread is creating a brand new socio-economic landscape’ that generates specific forms of ‘social control’ (Durand, 2022:36). It is exactly this new social space that they create and control that allows them to create data through the surveillance and datafication of their users. Users are not seen as humans on a platform. From the perspective of the platforms, they are socio-legal and technological constructs created in the interaction between users and the technologies of these companies. Data gathering is the central dimension of this new economy of scale and it are exactly these massive investments that are needed to create such a platform of scale that shapes the digital economy in the playing field of only a handful of huge players. On a global scale, we see that ‘the platform’ has become a new, very powerful and dominant business model that is characterized by ‘providing the infrastructure to intermediate between different user groups, by displaying monopoly tendencies driven by network effects, by employing cross-subsidization to draw in different user groups and by having a designed core architecture that governs interaction possibilities’ (Srnicek, 2017: 48).

The latter is important: digital media are not just powerful mediators of discourse, they ‘govern’ the interaction possibilities, and they do this from a position of power. Note that this power is economic and cultural, but not democratically elected. The governing of interactions on their platforms takes the form of directing, steering and triggering user behavior. Certain discourse practices are stimulated and others are discouraged (updating on a daily or even hourly basis is preferred to never or rarely updating, uploading videos over text, uploading short texts over longer texts and so …) or even forbidden (hate speech, conspiracy theories, …). At the very least, we see that digital platforms create certain boundaries for discursive action. But even within the boundaries, it is clear that platforms like Google will award certain practices with visibility (and/or financial gains) by showing them on the first page of search results, while others are pushed into oblivion. These choices are never neutral, they are ideological: they are connected to larger discourses on truth and falsehood, on relevance and irrelevance, and thus also on accepted and less accepted ideas.

How people connect with each other, be it in the context of labor or in their leisure time, is constitutive of societal relations and thus in last instance of society. Both Simmel and Goffman have argued throughout their careers that the big things in society, in actual observable reality are made up of a dynamic and complex system of interlocking and interacting small things (Maly, 2017). The fact that digital media format or govern our interactions, has, according to this logic, impact on society in general. For the study of ideology, it is thus key to keep in mind that, in contemporary post-digital societies, ideologies have the shape they have not only as the result of the whole field of social struggle between the different groups, but also because these ideologies are co-constructed by digital media.

To conclude this section. Researching the ideological role of the digital economy within or beyond capitalism starts by realizing that platforms are base and superstructure in one. How platforms operate and with which goals is an important precondition to understand (1) how they impact social relations, (2) how they have an ideological impact and (3) how we can see this ideological impact in relation to the base, the actual techno-economic infrastructures.

Digital economy and digital culture

For the sake of clarity, in what follows, I’m going to narrow down the notion of platforms to social media platforms and focus on how platforms direct or govern user interaction. This choice of course shouldn’t be read as claiming that only social media platforms are facilitating new social relations, relations of production and (digital) culture. The contrary might actually be true. The choice is in first instance a practical choice. Secondly, it is hard to deny that social media platforms are the ones that speak most to us if we want to zoom in on the relation between digital economy and digital culture. Central to the social mediatization of society is not only that they ‘democratize’ media access, but maybe more importantly that they turn their users into prosumers (Miller, 2011). Their online presence is turned into data that can be used to construct productive models that in turn are sold in different shapes to advertisers. Their social lives are cannibalized. But there is more. Platforms instruct people to participate in certain discursive practices (be it in the form of liking, commenting or sharing or in producing status, videos, reels or any other content format). Or more concretely; users are directed to produce popular content.

The focus on ‘data’ is what drives the lowering of the threshold of what counts as producing content and what is defined as qualitative content. Even users who never actually produce content in the classical sense, are contributing to the profits of those platforms. Scrolling and viewing are acts just like posting, liking, sharing and commenting. They all equal ‘producing data’. An active smartphone in your pocket on holiday is enough to contribute to Google Maps but also to Facebook’s or Instagram’s profits. Digitalization is so omnipresent that not ‘producing data’ is almost impossible. Digital labor (if we can call it a such) is a continuum: from switching your smartphone on to actually producing content. This entire continuum between having a smartphone and creating likeable content is a fuzzy but profitable space. Digital media contribute to the realization of a classic neoliberal rule: the extension of commodification processes to all aspects of life (Harvey, 2005).

Platforms not only organize specific relations between users, companies and clients, they also give meaning to these relations.

In order to succeed in harvesting our data, and thus steering our social relations, platforms need to create ‘frictionless interfaces’ (Sadowski, 2020: 4). The steering shouldn’t feel as steering, but as a normal and natural way — and thus something we do not think about — of facilitating communicating, while at the same time triggering or creating needs and desires. Let’s take the metrics of social media platforms as an example. Metrics — the number of likes, comments, shares, etc. — have a central role in activating users and turning them into ‘active’ producers because they connect to our needs to be social beings. They are ‘proof’ of our meaningful interaction with others. What Marwick (2013) calls ‘web 2.0 ideology’ is intrinsically connected to the economic base of the contemporary digital economy. The more people interact, the more data is produced. But also; the more content people produce, the longer others stay online to consume content and thus the more data can be extracted. Venturini (2020) therefore sees the influencer or micro-celebrity culture as an important fundament of the social media economy. By grabbing the attention of users, influencers enable the extraction of data by platforms. This data is in turn used to connect advertisers with the ‘right audiences’.

It is not a coincidence that within those social media platforms the ‘Follow your passion’ or ‘Do What You Love’ discourses are so omnipresent. These discourses — produced by influencers — portray digitalization as a unique opportunity to make money by doing what your love. Whether it is restoring cars, trying out make-up, refurbishing furniture, another artisanal craft, or just entertainment: digital media seemingly allow people to become who they are and make money out of this. But taking the step to become fully integrated in the digital culture of a platform, and subsequently become a professional influencer, usually doesn’t happen overnight. It takes many hours, weeks, months and years of unpaid digital labor. It means learning to understand the mechanisms of the platform, the community guidelines, the platform cultures and of course the algorithmic environment. It also means that the would-be influencers learns how to edit videos, make thumbnails, analyze the metrics, create a community and so on. Duffy coined this ‘aspirational labor’. Aspirational laborers, she argues, ‘pursue creative activities that hold the promise of social and economic capital’ (Duffy, 2015: 3). These aspirational laborers inject free labor in the system, and contribute substantially to the possibility of data extraction by keeping people hooked (Eyal, 2014).

The engine of such aspirational labor is the Digital (American) dream. This digital version of the American dream promises that this free labor, in the long term, will allow people to live the life they dream of. That they will become successful. Central to that culture is a competition to grab the limited supply of attention: only those influencers who succeed in attracting attention will be rewarded with visibility and financial gains. Social media platforms are arenas of struggle. Once we are integrated in a platform culture, all kinds of mechanisms — of which metrification and the fear of invisibility are maybe the most important — become drivers to ‘produce’; to commodify evermore parts of our lives in the hope to grab eyeballs. Ergo, we are all becoming pawns in a world that is dominated by algorithms, datafication processes and changing interfaces that lure us into producing data and connecting to sellers.

Even though cultural and ideological differences are legio on platforms, on a meta-level we cannot ignore the cultural functioning of all these platforms. Each new feature, each new tweak of the algorithm and each new lay-out has general cultural effects. Social media platforms are the format in which users make culture. It is exactly in this sense that digital platforms are ideological: they define the contours in which legitimate or at least successful and thus visible culture is produced. Platforms, argues Durand (2022: 35) have within the space they govern ‘the means of socio-economic co-ordination’.

The reproduction of platform ideologies

Platforms not only organize specific relations between users, companies and clients, they also give meaning to these relations. When Meta describes its mission as ‘Bringing people closer every day’ it is not necessarily lying. Meta is indeed facilitating and programming sociality. When Meta claims that they give ‘people the power to build community and bring the world closer together’ or that they ‘empower more than 3 billion people around the world to share ideas and offer support’ they are describing, or at least try to give meaning to, user behavior on their platforms. At the same time, it is obvious that such slogans obfuscate the raison d’être of the platform which is the extraction of data — and the subsequent creation of profits for their shareholders. That these reasons are never mentioned in these user-directed discourses — even though they are the essence of the platform — shows the ideological nature of these reasons. Althusser wouldn’t be surprised that the real economic goals and relations of production are obfuscated in Facebook’s discourse. ‘All ideology’, he argued, ‘represents in its necessarily imaginary distortion not the existing relations of production (and the other relations that derive from them), but above all the (imaginary) relationship of individuals to the relations of production and the relations that derive from them. What is represented in ideology is therefore not the system of the real relations which govern the existence of individuals, but the imaginary relation of those individuals to the real relations in which they live’ (Althusser, 2020: 39).

Those real relations in a platform economy, and in Facebook in particular, are clear. Facebook does indeed let people connect and interact, and it can help people to make money. But it does of course much more than that. The surveillance and datafication of that behavior, as we have seen, turns user interaction into raw data that can be sold in the form of predictive models. This in turn is then used

- to tweak the system in a way that lets users see the connections and content that lets them stay online,

- to technically improve the platform itself so that it becomes more efficient for the users, and in extracting data (in term of profit generation and attention grabbing)

- to tweak connections with customers paying Facebook to get users’ attention.

In other words, Facebook determines how and with whom people connect. From this perspective, Meta’s sales pitch of Facebook gets a different ring to it:

“Let's find more that brings us together. Facebook helps you connect with friends, family and communities of people who share your interests. Connecting with your friends and family as well as discovering new ones is easy with features like Groups, Watch and Marketplace.” (Meta, 2023: Facebook).

Note what is completely absent here: (1) the fact of harvesting data and (2) the fact that companies pay Facebook to access specific audiences. The real relations of production are replaced by largely imaginary ones. In the latter, the individuals are happy, free, connected and empowered by Facebook. In reality, we see the opposite: users’ data is exploited, the connections they make are not free but steered, and the company and its customers are empowered. The frictionless interfaces are not only a matter of design that feels natural and organic, they have an ideological function as well. They contribute to the notion that platforms are only there to help us connect, interact and inform ourselves. Platforms are just forces for good.

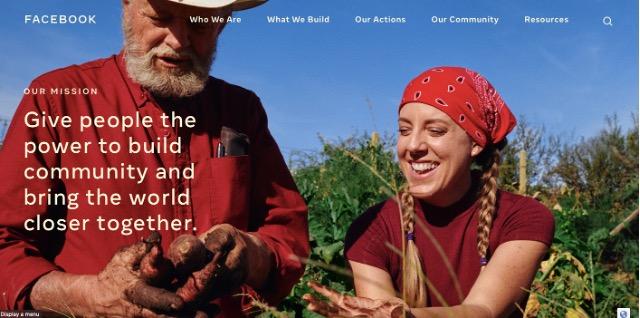

Image 1: Facebook's about page 2022

Facebook as a company, is an active player in articulating a specific media ideology (Gershon, 2010). This media ideology has a long tradition, it goes back to what Turner (2006) has called digital utopianism. Turner sees in Stewart Brand and his Whole Earth Network and shows the start of the fusion of counterculture values — including back to the land movements-, cybernetic theories and neoliberal libertarianism —into a techno-liberating narrative. Barlow’s famous Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace is emblematic of the anti-government stance of this digital utopianism. Cyberspace was described as a global place where minds could come together, ‘a world where anyone, anywhere may express his or her beliefs, no matter how singular, without fear of being coerced into silence or conformity’ (Barlow, 1996). A world also where governments have no sovereignty. Central in that new world was the liberated individual that could connect with people around the world. In Facebook’s version of digital utopianism, technologies are also framed as liberating and empowering. Technology, it seems, is inherently progressive. In image 1, we see Facebook’s mission in words and in one carefully chosen image. The essence of Facebook, so it seems, is to ‘Give people the power to build community and bring the world closer together’. The image of the young women and older man adds meaning to what this ‘bringing closer’ can mean. We see an intergenerational relation that is clearly inherently happy. Both the older man, and the young women have smiles on their faces. Man and woman are closely connected to the soil — harvesting carrots under a clear blue and sunny sky —; a strong metaphor of being part of a local community. Technology is so frictionlessly integrated in daily life, that it is completely absent from the picture. It is Facebook’s mission slogan that lets us see this pictured relation as the effect of technology that brings people together as people, and as part of a local community. In Facebook’s discourse, there is no contradiction between local and global communities, between nature and technology and between young and old.

Zuckerberg articulates this mission of Facebook more explicitly in his famous Facebook post Building Global Community (Zuckerberg, 2017). In this post, he argues that ‘Facebook stands for bringing us closer together and building a global community.’ ‘In times like these,’ Zuckerberg argues, ‘the most important thing we at Facebook can do is develop the social infrastructure to give people the power to build a global community that works for all of us’. In times like these, of course refers to the election of Trump and the rise of other far-right populist movements and politicians around the world since 2016. Facebook, implicitly, positions itself as a progressive medium, as pro-globalization but also as a new form of post-state social infrastructure on parwith nations and governments: ‘History is the story of how we've learned to come together in ever greater numbers -- from tribes to cities to nations. At each step, we built social infrastructure like communities, media and governments to empower us to achieve things we couldn't on our own.’ (Zuckerberg, 2017). Social media, in Facebook’s narratives, is thus more than just a platform, it is framed as a social infrastructure. And not just any infrastructure: is imagines itself as a post-state infrastructure that can over (a lot) of the tasks that governments used to organize not just ‘a people’, but humankind. Facebook as a post-state institutions is communicated as an actor of change that can help bring humanity together. ‘Building a global community that works for everyone starts with the millions of smaller communities and intimate social structures we turn to for our personal, emotional and spiritual needs.’ The local and the global are and can be connected according to Zuckerberg, and it is Facebook, among others, that can help realize this. Facebook, ‘as the largest global community’, (…) can explore examples of how community governance might work at scale.’ Facebook is not just on par with nations, it is quite obvious that its CEO sees it as the follow-up on a global scale. Zuckerberg sees technology as a tool to create a better world, connecting people should allow them to form communities, to get informed and be safe, to pay, but also to engage in the political process. Facebook in this sense is constructed as an instrument that can help to create a benevolent global community, it is a new form of ‘government’ (Beekmans, Maly & Van Hout, 2023) presenting a new form of organizing society.

A media ideology, especially when shared by users, shapes the way the users think about and use that medium. Facebook can say what it wants in its promo-discourse, if the users disagree, protest, or leave the platform, it’s platform ideology would lose its functionality or they will adjust their values, norms, settings and affordances (something we see happening since 2016). Facebook may not be the hippest platform of them all, it is still a densely populated space where users are happy to comply with the environment that Facebook has created for them. This starts with the first letters they type when they register. The real name policy, according to Bucher (2021: 76-77) is the foundation of Facebook’s business model, as it wants to connect costumers — the actors that are paying for their ads — to real people. This business decision wasn’t logical in 2004, when most of the internet users used handles, but it has been accepted by a large majority of people. And quite a lot of them will discuss their use of Facebook in similar terms as the marketing pitch from Meta: as a site where people connect. It shows how Meta and Facebook act as centering institutions. Centering institutions impose a certain doxa in a particular group. ‘This function is attributive’ argues Blommaert (2005: 75): ‘it generates indexicalities to which others have to orient in order to be ‘social’, i.e. to produce meanings that ‘belong’ somewhere.’ The centering institutions — by generating an order of indexicality — produce perception and/or real processes of homogenization and uniformization. If one wants a voice on Facebook (and all other social media platforms for that matter), one has to adjust oneself to the norms that are embedded in the algorithms, community guidelines and affordances of the platform. In other words, digital media generate certain norms and rules that give direction to specific behavior. In the context of Facebook, this not only means using one’s real name, it also means amassing algorithmic knowledge (Maly, 2018) and producing discursive behavior that lives up to the platform’s expectations in terms of rhythm of posting, type of content and networking practices.

Ergo, in the discursive practices of users, we see if and how Facebook’s ideology is reproduced. We shouldn’t necessarily mistake this for a belief in or support for Facebook’s ideology, but it is emblematic for the power of the social platform over the social relations between users, and how users behave within the context of the platform. This uptake is, even if it is only orthopractically, crucial in understanding platforms as an ideological apparatus (Maly & Beekmans, to be published). Important to realize is that media ideologies are not created in a vacuum, they resemble dominant ideologies from the sector, and from (dominant groups within) society at large. Platforms exists as layered, stratified and polycentric ideological apparatus by synchronizing many different ideologies into one structure operating in a certain territory. They can combine the digital utopianism of the Californian ideology, the neo-feudal view on users with the neoliberal economic policies and the liberal moderation juridical rules of the state. The result of that specific synchronization of ideologies creates a specific platform that steers user behavior in specific ways. The affordances and interfaces of those platforms create a specific grammatical system to be used that at least partially directs communication (Cara, 2019). As a result of this, each social media platform not only has its sharedness with other platforms, it usually also has its own aesthetics, affordances and interfaces that contribute to the growth of specific platform cultures and discursive practices that flourish on them.

From a digital discourse analytical perspective, this means that we need to direct attention not only to human discourse, or analyze digital discourse as a socio-technical assemblage but also focus on the role of these platforms as ideological and thus discursive actors. The ideological impact of these platforms can of course not be limited to the discourse they produce about themselves, their algorithmic organization, affordances or the interfaces. We also need attention to the uptake and reproduction of that ideology on the platform (Maly, 2022). Especially on social media platforms, that means carefully paying attention to the reproduction of platform ideologies by key influencers.

In a follow up paper I zoom in on Gary VaynerChuck or GaryVee as he is usually called, not so much as a person in his own right, or a successful influencer, CEO or entrepreneur, but as an ideological actor or broker. Or more concretely; as somebody who embodies and reproduces social media ideology.

References

Althusser, L. (2020). On ideology. London: Verso.

Barlow, J.P. (1996). A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace. The Electronic Frontier.

Beekmans, I., Maly, I., & Van Hout, T. (2023). ‘Here in the US’: Identity narratives, national beliefs and corporate governance values in Big Tech Hearing discourse. First Monday, 28(5). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v28i5.12803

Blommaert, J. (2005). Discourse, a critical introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blommaert, J. (2010). A sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bucher, T. (2018). If…. Then. Algorithmic power and politics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Burgress, J. Albury, K., McCosker, A. & Wilken, R. (2022). Everyday data cultures. Cambridge: Polity Press.

Byerly, C. and Ross, K. (2006). Women and Media: A Critical Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Chadwick, A. (2017). The hybrid media system. Politics and power. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chun, C. (2017). The discourses of capitalism. Everyday economists and the production of common sense.London & New York: Routledge.

Duffy, B. E. (2015). The romance of work: Gender and aspirational labour in the digital culture industries. International Journal of Cultural Studies, (), 1367877915572186–. doi:10.1177/1367877915572186

Durand, C. (2022). Scouting Capital’s frontiers. Reply to Morozov’s ‘Critique of Techno-Feudal Reason’. New Left Review, July August 2022.

Eagleton, T (1991). Ideology: an introduction. London: Verso.

Eyal, N. (2014). Hooked. How to build habit-forming products. London: Portfolio Penguin.

Fuchs, C. (2015). The Digital Labour Theory of Value and Karl Marx in the Age of Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Weibo. In: Fisher, E., Fuchs, C. (eds) Reconsidering Value and Labour in the Digital Age. Dynamics of Virtual Work Series. Palgrave Macmillan, London. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137478573_2

Fuchs, C., (2021) “The Digital Commons and the Digital Public Sphere: How to Advance Digital Democracy Today”, Westminster Papers in Communication and Culture 16(1), 9-26. doi: https://doi.org/10.16997/wpcc.917

Gerschon, I. (2010). The Breakup 2.0. Disconnecting over New media. Ithaca & London: Cornell University Press.

Harvey, D. (2005). A brief history of neoliberalism. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keane, M. & Yu, H. (2019). A digital empire in the making China’s Outbound Digital Platforms. International Journal of Communication 13(2019), 4624-4641.

Lewis, R. (2018). Alternative Influence: Broadcasting the Reactionary Right on YouTube. Data & Society.

Maly, I. (2017). Saabs and Saabism. A Digital Ethnographic analysis of Saab culture. Tilburg Papers in Culture Studies, nr 188.

Maly, I. (2018). Nieuw Rechts. Epo: Berchem.

Maly, I. (2020). Metapolitical New Right Influencers: The Case of Brittany Pettibone. Social Sciences, 9(7), 113. MDPI AG.: http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/socsci9070113

Maly, I. (2021). Vooruit! Politieke vernieuwing, digitale cultuur en socialisme. Berchem: EPO.

Maly, I. (2022a). Populism as a Mediatized Communicative Relation: The Birth of Algorithmic Populism. In C.W. Chun (Eds.). Applied Linguistics and Politics (pp. 33–58). London: Bloomsbury Academic. Retrieved May 8, 2023, from http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350098268.ch-002

Maly, I. (2022b). From methodology to method and back. Some notes on digital discourse analysis. Diggit Magazine.

Maly, I. (2023). Metapolitics, Algorithms and violence. Far-right activism and terrorism in the attention economy. London & New York: Routledge.

Maly, I. & Beekmans, I. (to be published). Discourse analysis of Digital media.

Maly, I., & Varis, P. (2016). The 21st-century hipster: On micro-populations in times of superdiversity. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 19(6), 637–653. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549415597920

Mandel, E. (1994). The place of Marxism in history.

Mandel, E. (1980). Het historisch materialisme. Marxists.org

Marwick, A.E. (2013). Status update. Celebrity, publicity & branding in the social media age. New Haven & London: Yale University Press.

Miller, V. (2011). Understanding digital culture. London: Sage.

Morozov, E. (2016). Tech Titans are busy privatizing our data. The Guardian, 24 April.

Morovoz, E. (2022). Critique Of Techno-Feudal Reason. New Left Review, 133/134, Jan -Apr.

Sadowski, J. (2020). The internet of landlords: Digital platforms and new mechanisms of rentier capitalism. Antipode Vol. 0, No. 0, 2020 pp. 1-10. Doi: 10.1111/anti.12595

Srnicek, N. (2017). Platform capitalism. Cambridge: Polity.

Störm, T.E. (2022). Capital and Cybernetics. New Left Review 135, May – June 2022.

TeamGaryVee (2020a). What Is “Day Trading Attention”? Gary Vaynerchuk.

Turner, F. (2006). From Counterculture to cyberculture. Stewart Brand, the whole Earth Network and the rise of Digital utopianism. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Tokumitsu, M. (2014). In the name of love. The Jacobin.

van den Hoonaard, W.C. (1997). Working with sensitizing concepts. Analytical field research. Qualitative research methods series 41. Sage University paper.

van Dijck, J., Poell, T. & De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society. Public values in a connective world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

van Dijck, J. (2013). The culture of connectivity. A critical history of social media. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Varoufakis, Y. (2021). Techno-Feudalism Is Taking Over. Project Syndicate.

Zuboff, S. (2019). Surveillance capitalism. The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. London: Profile Books.