Research report: analyzing Facebook's Guidelines for publishers

On March 1st 2018, Diggit Magazine set up a Facebook experiment: for one day we tried to (1) follow the Facebook Guidelines for Publishers in detail and (2) to carry out a smallscale experiment that would hopefully give us some insights in the working of the algorithms and, more importantly, could enable us to set up more complex research experiments in the future.

Reading The Facebook Guidelines

The starting point of this experiment was the announcemen byFacebook creator and CEO Mark Zuckerberg that he would ‘fix Facebook’ in 2018. In a series of blog posts, he announced several upcoming changes in the Facebook algorithms. Mainstream media engaging in the Facebook Journalism Project were referred to the ‘Facebook Guidelines for Publishers’ if they wanted to know how to use Facebook as a publishing tool. Diggit Magazine decided to analyze these guidelines and find out what Facebook expects of publishers.

In that document, Facebook presents itself as a tool and a platform publishers can use. Facebook reaches out to publishers andhe message seems to be that the medium is not a competitor and not an editor either. Facebook presents itself as a technological solution for publishers. The only thing they have to do, besides creating ‘important and meaningful stories’ is understanding that tool called Facebook and to follow its guidelines. This is where it gets interesting: the guidelines stipulate the ‘ideal publisher on Facebook’: the publisher that uses and thus reorganizes their production in order to use Facebook to the full. From the moment one puts all these guidelines together, you see how Facebook cannot be seen as a neutral technological tool: the Facebook guidelines not only promote certain types of content, they also create a very particular environment.

The audience

‘The audience’ or better ‘your audience’ has a central place in that environment. Publisher guideline one is clear: ‘People on Facebook Value Content That's Meaningful and Informative’ (Facebook, 2018). ‘The people’ are out there. They are the key-product Facebook has to offer to publishers and Facebook claims to know what the ‘people’ want. The technological solution that Facebook offers publishers to reach that audience is the News Feed: ‘The goal of News Feed is to connect people to the stories they care about most.’. The ‘people’ or in Facebook rhetoric ‘our community’, is constructed as an enormously fragmented audience. The News Feed does not present the news or stories with the highest quality, or the most important and meaningful ones, but the news that ‘the user’, that is the individual Facebook user, ‘cares’ about.

As we all know, the users of Facebook are hardly questioned on what they would like to see in their News Feed. Facebook still speaks in name of the individual Facebook users and its algorithms organize content in that News Feed on the basis of:

- An Inventory of all the content that has been produced by your friends and pages

- Categorizing the content on the grounds of following criteria:

- Who posted it, when, internet connection, time,

- Form, title, image, text, ….

- Prediction: the algorithm tries to predict how the individual user will interact with the post

- What are the chances that the individual user will click on, comment on, share or like a piece of content.

- This prediction is based, among other variables on your relation with the poster (many personal signs, Facebook, 2018: 4)

- In 2018, clickbait, like-bait, engagement-bait and comment-bait will be suppressed.

- A Relevancy score is attached to content.

- On the basis of that score, the algorithm decides whether or not the post will pop up in one’s newsfeed

So Facebook's claim that they “are not in the business of picking which issues the world should read about, but we are in the business of connecting people with stories they find most meaningful’ (Facebook, 2018: 2-3) is dubious. Facebook clearly does pick the issues the individual reads about, but does so on the basis of the algorithmic Facebook identity of the user. In the end, it is Facebook that decides what the individual really wants and it does so on the basis of big data on their audience.

Implicitly, Facebook sells itself as an excellent and seemingly neutral tool for publishers to create, find and reach out to audiences. The only thing publishers should be worried about, according to Facebook, is ‘making the important and meaningful stories interesting to their audience’ (Facebook, 2018). ‘Their audience’ is of course a Facebook construct: one can only build up ‘an audience’ as a publisher if one succeeds in popping up in people’s timeliness. From the moment one has ‘an audience’, Facebook urges publishers to utilize “Facebook insights features to see what content is resonating with your fans on the platform.”

Track, monitor and surveil your audience

Facebook urges its publishers to track monitor and surveil the behavior of their audience on their Facebook page. Moreover, Facebook wants publishers to insert Facebook Pixel to track activity on their websites and on the internet in general.

- To track user behavior on their site, Facebook suggests to install The Facebook Pixel is ‘a piece of JavaScript code for your website that enables you to measure, optimize and build audiences for insights or Facebook ad campaigns.’ The Pixel Base Code tracks activity on your website, providing a baseline for measuring or creating simple rule-based audiences. Beyond tracking basic website visits, there are likely important actions that your audience may take on your website that could be helpful for tracking or retargeting an audience.

- To track the sharing behavior of your user by using Search and Link Checker. Set up saved searches around your domain and

- To track posting behavior by using Link Checker (or Chrome Extension) to see who is posting your content on a regular basis.

The audience on Facebook is thus a datafied audience and the medium is set up as a technological interface to monitor, track and datafy that audience. Based on the profile of that datafied audience, content has to be created. What constitutes quality and what meaningful information is, is thus not only quantified, in reality it has nothing to do with the quality of the content. What is understood as ‘meaningful’ by Facebook is something that resonates with an audience and publishers are urged to reverse roles: Facebook does not help them to find an audience for their content, but presents a datafied audience for which publishers should write personalized content.

The audience, in terms of Facebook profiles that can contribute to the construction of virality, should determine the content. Publishers are advised to ‘Use keywords (and lists) to funnel story ideas to your writers. Set up some combination of daily emails, rolling digests throughout the day and/or viral alerts based on both lists and keywords to both keep your writers and editors up-to-date on the biggest social stories and uncover great content coming from small and unknown sources[MO1] .’ (Facebook, 2018)

Facebook as an audience market place

Facebook controls publishers' access to their audience. Even followers of a certain publisher’s page do not necessarily see their posts. Facebook sells this as a plus: ‘News Feed uses a variety of diversity rules to prevent people from seeing too many stories from a given publisher. That means you don’t need to worry about spamming your fans or followers provided that the content you post is new and high quality’ (Facebook, 2018). Publishers are pushed to publish frequently. What's more, the medium pushes publishers to post different types of content: not only links to articles on the publishers' website, but also introducing Facebook-only content, such as Live Videos, pictures and instant articles.

Your content enters a marketplace with other publishers competing for an audience. Publishers should ‘Pop in a Leaderboard to see who's winning the day among your industry peers and use the post streams to help track everything in one place and figure out what the biggest social moments are.’ Publishers should thus not only monitor their audience, but also their ‘competitors’. They should build lists of their competitors and set up viral alerts to get notified on ‘large stories’; ‘use CrowdTangle's Intelligence feature to see the highs and lows of your Page and how your Page stacks up against competitors over any timeframe.’

Facebook not only reverses the role between publisher and audience, it also pushes publishers to produce certain types of content and to adapt their content to social media: “Improve the framing you use when you post a story to social. Before you post a story to Facebook, you can use the keyword search to see how similar stories are doing on social and what headlines, images, angles, etc. are working the best to help you shape the approach you take.” (Facebook, 2018). Facebook formats the content of publishers, and it favors content that aligns with the formats Facebook likes. The first rule is, that every publisher should ‘(u)se diverse storytelling tools to tell your stories’ (Facebook, 2018). Publishers shouldn’t just post links to articles on their website, they should also use Facebook Live Videos. Each of these content types is highly formatted by Facebook. In the case of Live Videos, publishers should only post ‘High resolution’ videos, ‘have a strong connection’ when going live, ‘write a catchy description before going live’, use ‘captioning’ and use ‘narration or an on-camera host’ and when possible, they should use ‘scheduled live’.

Moreover, Facebook not only pushes publishers to engage with ‘trending topics’ using ‘predetermined formats’, it also introduces time as an important parameter for uptake. When something is ‘trending’, or when there are large events or major new stories, publishers should use ‘live displays (…) to track what’s happening in real-time. (Facebook, 2018). They should ‘Track what celebrities, athletes, business leaders, politicians and other influencers are doing on social.” (Facebook, 2018) and are urged to produce content fast: Be fast: ‘don’t wait too long to post on a trending topic’ (Facebook, 2018). To track the produced content and decide ‘if you want to put money behind it, push a credible story on other social accounts, repost at a later date, do a follow-up story, etc.’ (Facebook, 2018).

Facebook thus creates a highly competitive environment where publishers compete against each other to produce ‘personalized’ and ‘trending’ content. Content does not circulate because it is important or high-quality, but because the Facebook algorithms determine if the individual Facebook users that are part of ‘your audience’ will like, share or comment on the posts.

Setting up the experiment, part 1: #diggitday

Diggit Magazine was set up in the fall of 2016 as an academic, community-driven, news, information and reflection platform focusing on (digital) culture, globalization and arts. Injecting academic quality in the public sphere is one of its major goals. We value ‘slow’ content production that has been peer reviewed, checked and double checked. The overall goals and values that Diggit Magazine honors do not align with the vision Facebook is promoting as the ‘ideal type’ of publisher.

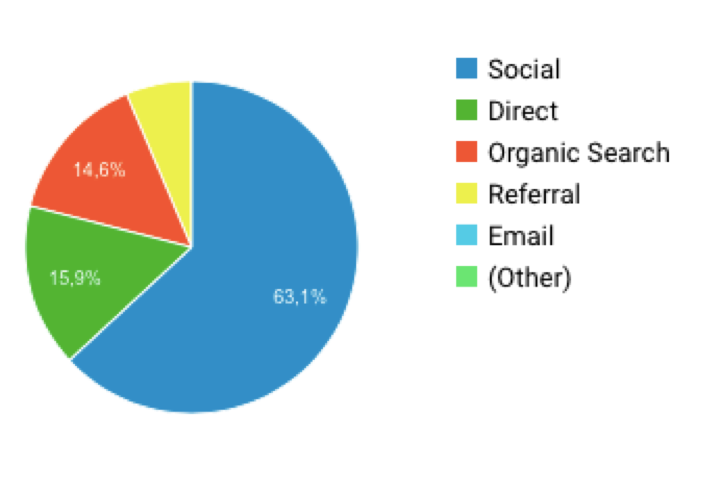

Traffic Sources Diggit Magazine

Nevertheless, we see that over 63,1% of our visitors find us through social media. Among these platforms, Facebook is the largest channel through which readers find Diggit Magazine, with a share of almost 77%. Twitter is second with a share of 11%. Facebook clearly dominates. This can be explained by a couple of things.

- First of all, Diggit Magazine is a very young medium, meaning that the more conservative algorithms of Google do not promote us as much as the more progressive algorithms of Facebook. Google is responsible for 97% of the readers who arrive on Diggit through organic search.

- Secondly, Diggit Magazine has a rather small Twitter base (325 followers). Compared to that base, the magazine has more than 2300 ‘fans’ on Facebook. Facebook thus provides the magazine with a platform for uptake.

Facebook is thus an important factor in gaining readers for Diggit Magazine. Up until this experiment, Diggit Magazine certainly did not follow (all) the Publisher Guidelines as stipulated above. Facebook was only used to let the page's followers know that there was new content available. Even though Diggit Magazine has an international audience[i], with a substantial amount of readers from the US, we publish around 9-10h o’clock in the morning, European time. On average, Diggit Magazine publishes 4 articles/papers per week. Apart from 4 videos, Diggit Magazine did not yet produce content for Facebook: We didn’t post Facebook updates, we didn’t use Facebook Live Videos and we did not post pictures of our authors, nor did we use Facebook instant articles or the publishing tool module.

In the context of the first experiment, this was all about to change. What was this experiment about? In order to understand how beneficial it is for a publisher to reorganize itself so as to meet the Facebook Guidelines, Diggit Magazine decided to try to meet as much of these guidelines as possible for one day. A small team of 25 Culture Studies students analyzed the guidelines, and prepared content for the experiment.

Following the guidelines, we produced different types of content for Diggit Magazine itself. Ranging from interviews and essays, overt articles and to columns to longer analyses. All content was prepared for SEO and SMO. We used colorful images that stand out and all content came with ‘truthful’ and ‘informative’ abstracts and titles. We made sure that the caption was short, pointy and triggering attention.

We also produced content that was to be used on Facebook itself: short and funky video-clips, 3 Facebook Live Videos that were announced before the actual airing. All had one host, who was used to doing Facebook Live Videos. We also set up an event later on the first of March that was also live streamed. All Diggit Content was announced one hour before publication with a professional picture of the author accompanied by a ‘quote’ to trigger curiosity in the audience. All of these actions follow Facebook's Guidelines perfectly.

Building up to #diggitday

To give the experiment some traction, we invested in communication. On February 22nd, one week before the experiment, and for the first time ever, Diggit Magazine went Live on Facebook to inform our audience about the experiment. The Live Video had 794 views, 10 shares and 25 comments.

Facebook Video to promoot #Diggitday

In the afternoon, at 15:45 CET (9:45 New York Time) we launched a video on Facebook explaining the experiment. This video gained traction quite fast (in the sense of likes, shares and comments), and following the guidelines we decided to boost the post to three target groups. All three groups can be considered as representative of the existing audience of Diggit Magazine: students in the Netherlands, Belgium and the UK and Lecturers working at Universities in the Netherlands and Belgium. The post reached 15,082 people, of whom 5,000 were organic and 10,000 were paid for. 7,948 people viewed the video, which generated 118 likes (44 on the post and 74 on the shares) and 33 shares.

Second promo-video #Diggitday

On February 27th, we launched a second promo-video: ‘Diggit magazine: Diggit Facebook Extravaganza!’ giving more detailed information on the experiment and invited our audience to be a part of the experiment. They were asked to take a look on the Facebook page and the website of Diggit Magazine on the first of March. This video reached 2,213 people in total and generated 1,346 views. This post was clearly less successful than the first promo-video, and we decided to boost it only to students in the Netherlands. Half of its total reach was organic.

Facebook Banner to promote #diggitday

On the same day, we also uploaded a special banner on Facebook, advertising the experiment on March first, using images of people who were involved with the event. We also created a Facebook event and announced it on our Facebook page. This post reached 6,500 people, 444 people viewed it and it got 38 likes. 41 people announced that they would join the lecture by Jan Blommaert and 98 said that they were ‘interested’.

Diggitday event with Jan Blommaert

The next day, February 28th, we started publishing Diggit Content connected to the main topic of the experiment: the effects of Facebook on the public sphere. The first contribution was a column with the title ‘The public intellectual trapped in the Facebook Bubble’. It reached 1,780 people, received 64 (35 on the post and 29 on the shares) likes, generated 10 shares and 2 reactions.

Promo-picture #diggitday

At 15:35h, we launched a professional picture of Diggit author Ruben Bastiaanse by Maud Schoonen, with the hashtag #diggitday, introducing content that would be published at 16.00h. The high-quality picture, the quote and the fact that an interview with Piia Varis would be published, we hoped, would give more readers a stimulus to check back on our page and hopefully check out Diggit Magazine later during the day.

Post interview Piia Varis

The post was quite successful: it reached 1,999 people, generated 32 likes and 2 shares. After this post, we still posted a couple of memes and informative posts on the experiment the following day.

Big Data- video

On the evening of February 28th, we published a Facebook Video on Big Data. Even though it was published at an hour that we did not expect that much traffic and we did not boost it, we reached 1,024 people, generated a total of 336 views with a total of 120 minutes' viewing time.

#diggitday.

Diggit Day started at

8:00 o'clock. in the morning with an advertisement picture of the author of the first article to be published on Diggit Day, together with an inspirational quote. At 9:30, The article itself This Brazilian newspaper decided to stop posting on Facebook reached 990 people, generated 30 likes and 5 shares.

Brazilian Newspaper - post

At 11:05, we set up a Facebook Live Video. We made sure that we had a high-quality connection, using the latest iPhone to set up the connection and there was one experienced ‘host’ in all the Facebook Live Videos, introducing the session. The viewers could see an interview with Piia Varis (Tilburg University) and after that, were informed about the second experiment. The video was picked up well: 2,675 people were reached and the video had 1,104 unique viewers. We did not boost the video. It generated 131 reactions and 25 comments on Diggit's Facebook page.

Going Live!

At 11:30, we published a picture of the author of the next piece of Diggit content (Daria), thus promoting the article Is big data making the world better?

From 12:00 o'clock until 13:00 o'clock, the second Diggit Experiment took place. The article by Daria Kholod was used for this, more detailed, experiment. This will be elaborated on later on in this report.

At 14:38h, following Facebook's Guidelines to engage with a ‘trending topic’, our writers were researching the app Vero. Vero was trending since the day before and was still huge on the 1st of March. In the Netherlands and in the US it popped up as a trending topic. We published a short column, with a custom-made banner and a provocative new take on the trending app. Even though it was posted at a bad time (too early for the US and too late in the afternoon for Europe), it reached 2,144 people. It gained 18 likes and 18 shares.

Writing about a trending topic

At 16:00h, Diggit went live once more, broadcasting a lecture by prof. dr. Jan Blommaert on the political and social impact of memes.

Facebook Live Video - #diggitday Event

6,500 people were reached with this post, of which 2,400 people actually viewed the video. In total 3,267 minutes of video were watched and the peak during the Live Stream was 47 viewers. It generated 272 reactions, comments and shares. This video was not boosted, so its rather exceptionally large reach was fully organic. The explanation for this success is manifold: (1) It was released at an excellent time: 16:00 aligns with 10 AM in New York and in Europe, a lot of people are commuting at that time, (2) It was announced days beforehand, (3) Jan Blommaert is an internationally known academic, with a large base on social media, (4) Jan Blommaert also announced his performance beforehand and shared it on his wall. (5) during the Live Stream, it was shared by 49 Facebook profiles and pages.

At 20:00h, the last post of the day was published, which was a short Facebook video on the Verso app. The video reached 565 people, 199 people viewed it and it generated 11 reactions.

Trending topic-video

Analysis of #diggitday data

In the days leading up to March first, following the Facebook Guidelines, we published different types of content: articles, essays, videos and gifs. We only boosted the videos that had organic uptake. On the day of the experiment itself, we had a steady publishing rhythm. We published three items on Diggit itself (two articles and one column); we went live two times, posted one Facebook video and several ‘advertorial pictures’. What do the data tell us?

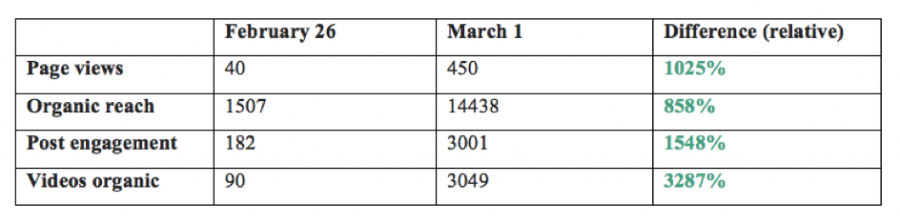

The first of March was, when it comes to reach on Facebook, an incredibly successful day. If we compare data from the day before the project started (February 26th) with ‘Diggit Day’ (March 1st), we can observe a huge increase in a lot of different areas:

The general hypothesis behind this experiment was that following the Facebook guidelines would not only lead to more interaction on Facebook itself, but would also result in more traffic to Diggit Magazine. With numbers like that, you might expect the number of people that visited diggitmagazine.com on March 1st to be huge. Surprisingly, this was not the case. Google Analytics is not displaying any striking differences between March 1st and most other days. There were a few more new visitors than on other days. This results in the average reading time being a little bit shorter, and the bounce rate being a little higher. These differences, however, are almost negligible.

Taking into account that we produced three times as much Diggit content that day and the fact that we engaged with a trending topic and mobilized 25 people to work on producing content and promoting content, we can only say that following the Facebook Guidelines, at least for a small publishers doesn't seem to be that beneficial. Of course, we are aware of the limits of this experiment. The Diggit Magazine Facebook page only has around 2K followers and likes. Moreover, the experiment only took place on one day and activities leading up to the experiment only took place during the week before that. One possible explanation is that the algorithms drive exponentially more traffic to a website when a certain threshold of followers and likers has been passed.

Small publishers can still use Facebook to find an audience, but all our data points to the fact that they should not invest in following the guidelines as their principal means of getting traffic to their site. There is no multiplicator effect of publishing a lot of content on one day, at least not in comparison to the extra investment that this brings along. The general rule seems to be that what works on Facebook is beneficial for Facebook. Or to put it differently, content that is exclusive for Facebook works best (Facebook videos, Live videos, pictures and memes). These different content types do not drive traffic to the website, but let content circulate on Facebook. Publishers that follow the Facebook Guidelines are in reality building traffic for Facebook, not for their own platforms.

Facebook should thus be seen more as a ‘branding’ machine than as a platform that connects an audience to your website. Circulating content on Facebook helps in gaining recognition and finding an audience. When, on February 22nd, we published the first post in the context of this experiment, Diggit Magazine had 2,350 likes on Facebook and 2,389 followers. On March 2nd, Diggit Magazine had 2,418 likes and 2,466 followers. A net rise of 68 likes and 77 followers in seven days. Unsurprisingly, on March 1st we gained the most likes in one day: 23 (losing 2) and the most followers: 31 (losing 2). Combine this with a total reach of 14,438 people in one day and you know that Facebook is still a useful medium to position yourself and make yourself known to a certain audience.

Setting up the experiment: part 2: What yields traffic.

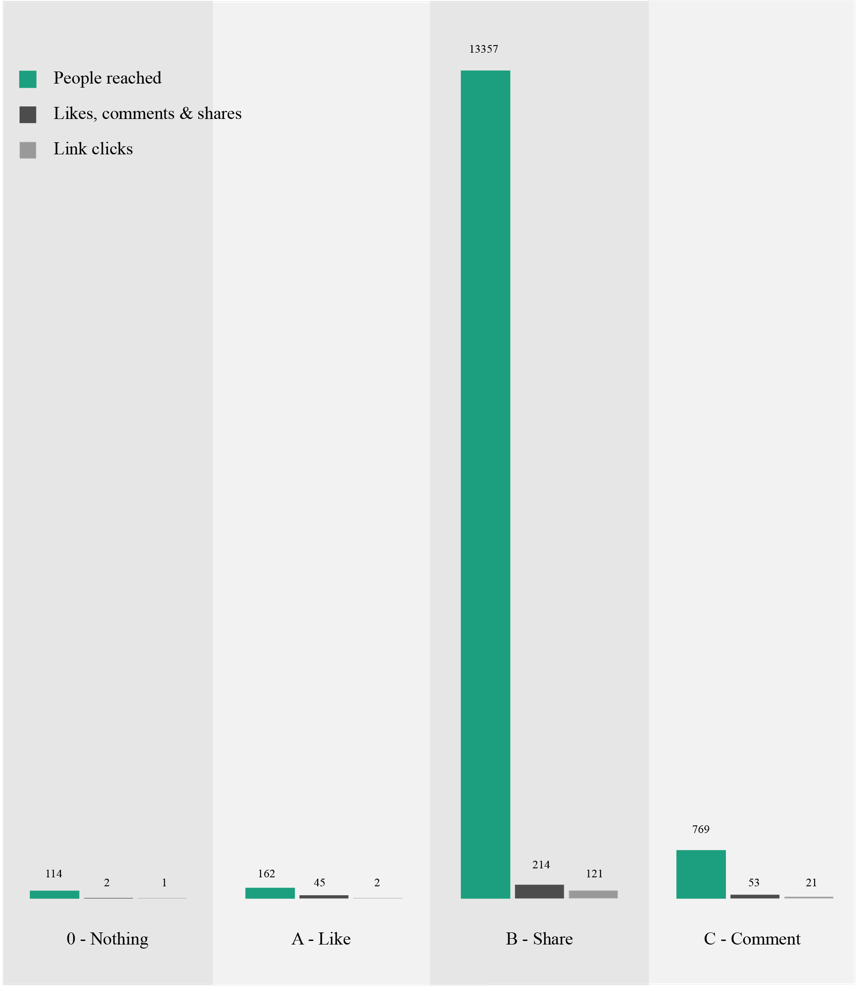

On March 1st, one small experiment was carried out as part of the total experiment. We decided to look at the impact the types of interaction on a post have. What makes a post go viral? What is more important for uptake: a Like? A share? A Comment?

In order to test this, we decided to post the exact same post three times, each time with instructions as to what we wanted our audience to do, and one time without any instructions for our audience. Each post had the same title, the same url, and the same caption. Considering the fact that Facebook has announced that it would downgrade all forms of ‘-bait’, we of course had to design the experiment in such a way that the algorithms would not see this experiment as ‘click-, like-, or comment bait’. That’s why we avoided any calls to action in the caption. We decided that we would add the call to action in the different header images. The image itself would be the same, only the call to action in it would differ.

Experiment 2: neutral post

All the posts were published between 12 o’clock and 13 o’clock. We have chosen this timing – lunchtime in the Netherlands - because it normally is a ‘low’ traffic hour. This would provide us with the best chances of controlling the interactions with the post. The original post – without instructions – was posted at 12:08. We decided to post this one first, because we suspected that Facebook would push it more than the duplicates in the newsfeeds of our potential audience.

Given the fact that Zuckerberg announced that ‘meaningful interactions’ would matter most, we had the hypothesis that long chunks of text and interactions in the form of interacting comments would produce the biggest uptake. Starting from this assumption, and the idea that the more a post was reposted, the more Facebook would suppress its circulation, we decided to post the different posts in the following sequence:

- version A of the initial post would ask people to ‘only like’

- version B of the initial post would ask people to ‘only share’

- version C of the initial post would ask people to ‘only comment’

These very concrete and narrow guidelines of course create biases. It is for instance impossible to say something about the relation between ‘interaction with the post’ and the ‘conversion rate’(clicking on the link that refers to Diggit Magazine). The only thing that we can say about these posts is about the ‘asked interaction’.

In order to set up the experiment, we informed our audience several times. On the day itself, we informed the audience through our Facebook Live Video and in the days before we gave the instruction to our audience to follow a post.

Instructing our test-audience

On 1 March, we added the following comment to this post:

"Dear Diggit Magazine readers, at 12 o’clock, we will be posting “Is big data making the world better?”. To partake within our Facebook experiment, we would like to invite you to; like article version A, share article B, comment on article C. To do this as orderly as possible, we added specific visual markers instructing you which article to like, share and which article to comment."

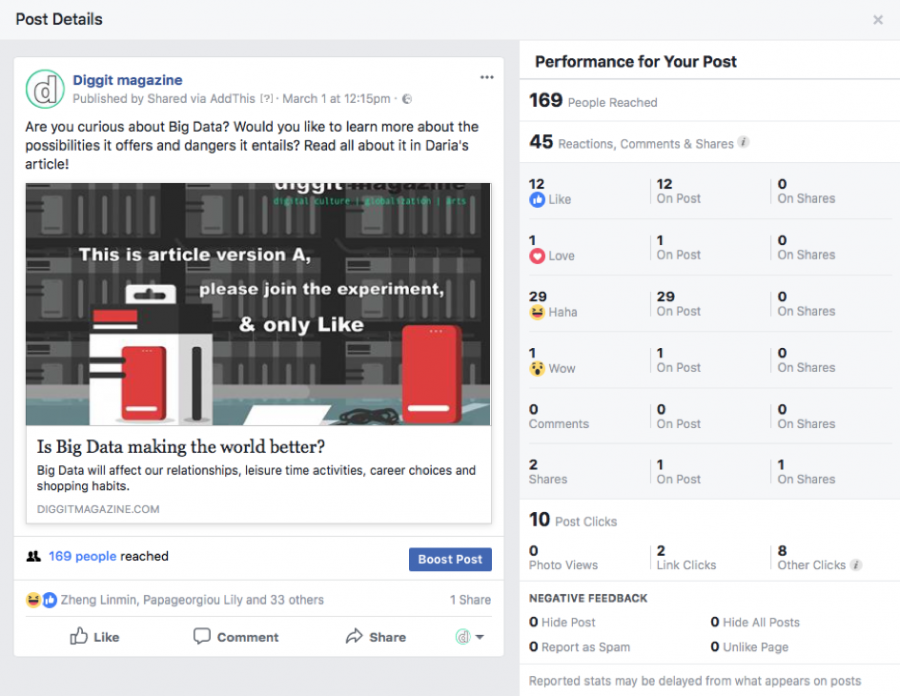

Post A: Please only like.

Version A of the experiment was posted at 12:15. The instruction to only like the video was added to the header image of the post. Even though 35 people liked it, the posted only reached 169. This is only 50 people more than the post without any interaction reached.

Experiment 2: version A

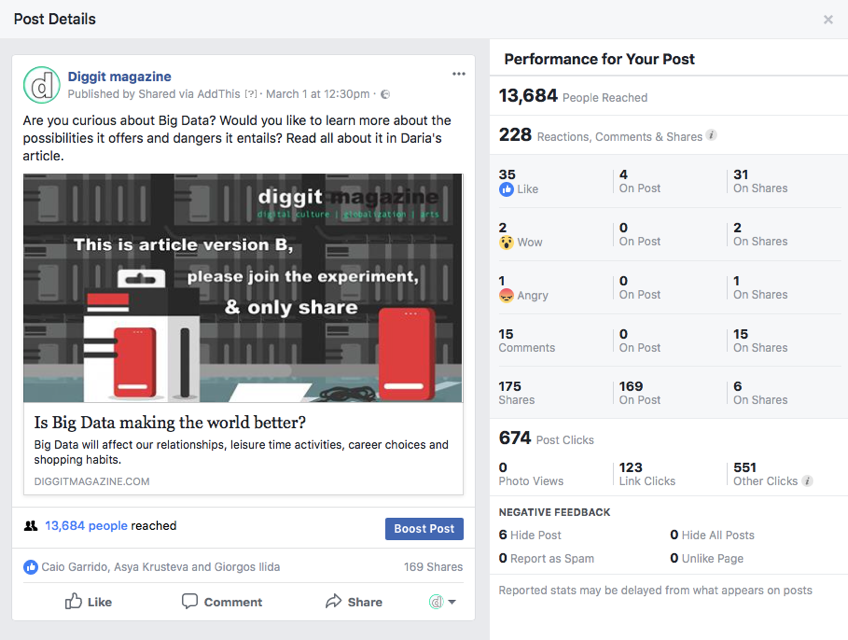

Post B: Please only share

Version B was posted at 12:30. Even though we asked to only ‘share’ this post, 3 people also liked it on the original post (and 31 on the shares). Considering that the effects of 44 likes was rather slim, we believe that these 3 likes do not have a substantial impact on the results of our test situation. The call for action was followed exceptionally well here: 175 people shared the post (169 from the original post and 6 shared it from a share). Even though the call to action only asked to share, we see that the post also generates 123 link clicks.

Experiment 2: version B - only share

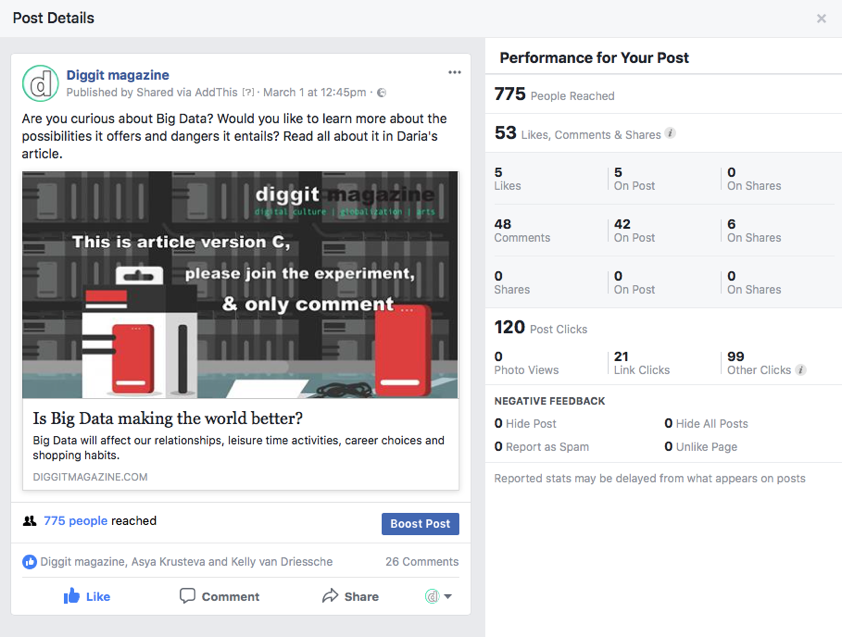

Post c: Please only comment

With post C, the audience was asked to ‘only comment’. The post received 48 comments (42 on the post and 6 on the shares). It reached 775 people and generate 21 link clicks.

Experiment 2: version C - only comment

Even though Facebook claims that ‘meaningful interaction’ will be rewarded the most, up to this day, this is not yet the case. According to Facebook analytics, shares are the most important tool to reach a large audience. Post B clearly managed to reach the largest amount of people; 13.357 in total.

However, what might be more interesting is the efficiency of the posts (or maybe, the lack of it). Of course, we should take into account that clicking on the link was not part of the experiment. We never asked our audience to click the link, and the calls for action were always framed in terms of ‘only’ like, share or comment. Bearing this in mind, we can still ask the question: ‘How likely was it that a person who saw any of these posts would click on it?’

Post 0: 0,87%

Post A: 1,23%

Post B: 0,9%

Post C: 2,73%

Post B had the highest reach, but if we look at the relative numbers, the chance that a person would click the link in the post (and therefore, visit diggitmagazine.com) was almost as low as it would have been if the post would not have been promoted at all. However, we should take into account here that the way the experiment was executed could be responsible for the low link click rate. As people knew this was part of an experiment and were explicitly asked to ‘only share’, we cannot know if they would have clicked on the link if it had not been part of the experiment. On the other hand, this bias was also present for Post C and this post was the most successful by far in terms of the link click rate.

Some concluding remarks

The two small experiments show that reaching a large audience on Facebook does not automatically translate to getting many visitors on your website. If it’s an online news medium's goal to attract as many visitors as possible, Facebook might not be the best platform to use. Facebook does provide traffic to the Diggit Magazine website, but when we compare this traffic to (1) the audience we reached on Facebook, (2) the formatting and labor-intensive investments that Facebook demands and (3) the quality of the Facebook driven visits (reading time, bounce rate), one could question the importance of Facebook for media.

Facebook seems first and foremost an important medium to acquire a name and to build a brand. It can drive traffic, but the difference between posting one ‘post’ per day and meticulously following the guidelines is small. The Guidelines seem to benefit Facebook more than the publisher. Following the guidelines means that one works for Facebook.

[i] The top 5 consists out of The Netherlands (23,5%), The United States (17,5%), Belgium (15%), United Kingdom (6,5%) and Canada (3%).