Being one of them: Participating in an online community while researching cultural heritage

Regional language, ranging from local dialects to an iconic accent, is an important part of cultural heritage and identity. Consequently, dialects and accents are also of significance for many online communities. This article deals with one of these communities: Brabantians who are involved online with their regional language.

Regional language, ranging from local dialects to an iconic accent, is an important part of cultural heritage and identity.

As a professor of diversity in language and culture I participate in this online community to share my expertise on language variation and cultural heritage. Yet, at the same time I am also doing research within the community and tap into the knowledge of the participants to gain new insights into their regional language, and hand these back to the community.

Policy work for a regional language community

When working on a new policy for regional language for the Dutch province of Noord-Brabant as part of the work for an external research chair with the Department of Culture Studies at Tilburg University — which is funded by that same province —, one thing became very clear: there was a necessity to find new ways to connect volunteers, professionals and others who were interested in Brabantish and to keep them involved through new media. To my conviction, to achieve this goal, the policy had to be focused on regional language in the broader spectrum; from regional accents to ‘old’, local dialects.

Regional language is important since it connects groups in our societies to geographical space, i.e. the region or place they associate with that language. A regional language community therefore is built upon a sense of belonging: feeling at home in Noord-Brabant.

A regional language community therefore is built upon a sense of belonging: feeling at home in Noord-Brabant.

We needed to come up with approaches that might help to preserve a regional language, make people more aware of its value, and empower the community of regional language speakers. In this sense, the new policy aimed to improve the image and prestige of Brabantish, and increase the knowledge of Brabantish and strengthen the underlying knowledge network. We believed these goals could be pursued through professionalization and digitalization, by developing a knowledge network and doing research, and through rejuvenation, developing talent and offering platforms. This might seem rather abstract, which is why I will discuss some of our work.

A new community

In May 2021, heritage consultants of Erfgoed Brabant (the cultural heritage foundation of the provincial authorities) and I started ‘Brabanders en hun taal’ (Brabantians and their language). ‘Brabanders en hun taal’ contains a Facebook-group, a newsletter via e-mail and a twitter-account. Furthermore, we organize bimonthly, publicly accessible sessions in Microsoft Teams, in which we talk about the value of home language, arts and regional language, documenting dialects and more, and in which we feature performances, presentations, or lectures.

In the Facebook-group community members post questions about dialects, and stories, poems, or humorous memes in dialect. Age does not seem to be a threshold; older members are not scared of joining. Perhaps this is a small benefit of the calamity called Covid; nowadays, we are all used to digital communication.

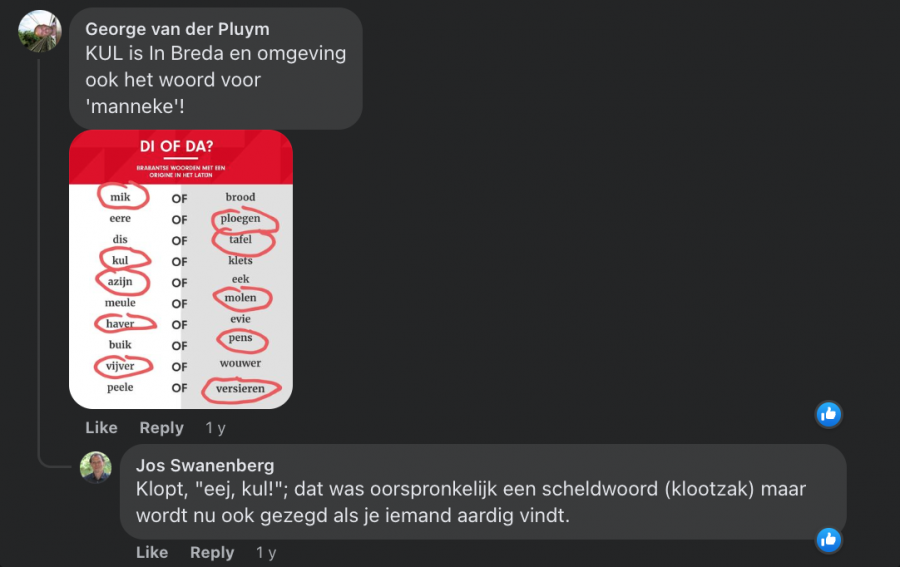

This screenshot shows a fragment of a conversation on the ‘Brabanders en hun taal’ Facebook page about the meaning of the word “kul”.

Some of the members of ‘Brabanders en hun taal’ are old acquaintances, like amateurs working on a dialect dictionary or singers who perform an oeuvre in dialect. Often, these ‘experienced’ language lovers already know each other from events such as festivals or contests. But the majority of Brabantians who now choose to get involved in their language on social media were unknown to us. Experience or not, just the will to be involved and share an interest is enough to become part of this community (cf. Blommaert & Varis (2013) on ‘enoughness’).

Adding and retrieving knowledge

As a scholar, I often answer questions and add information to discussions on the social media of ‘Brabanders en hun taal’. But being part of such a community also offers opportunities for citizen science (Ciolfi et al. 2017). The collective of the members in such a network provides highly valuable complementary knowledge. Each member has its own interests and expertise and is willing to exchange knowledge and experiences.

And even more: opportunities for online interaction might allow groups and individuals to exert more power over research. For instance by proposing new goals or directions for the research — in the case of this research; suggesting we make sure Brabantish survives as a regional language —, or by providing novel contextual information. In this sense, cultural heritage research within online communities could be transformed into empowering research (Cameron et al., 2020).

This screenshot shows some members of ‘Brabanders en hun taal’ commenting on a survey about their language. One person mentions she has “shared” it with other Brabantians, while another member writes he hopes a lot of people will also complete the survey.

In June 2021 some Erfgoed Brabant-colleagues and I investigated the knowledge of certain agricultural terminology as part of Erfgoed Brabant’s theme-months on Farm life and Dialects, and in July 2022 I tested the knowledge of certain ethnozoological terms, as part of Erfgoed Brabant’s theme-month on Nature, Landscape and Dialects. Using the affordances of Facebook and Instagram, we also involved followers of the social media accounts of Erfgoed Brabant, who share an interest in local history and folklore.

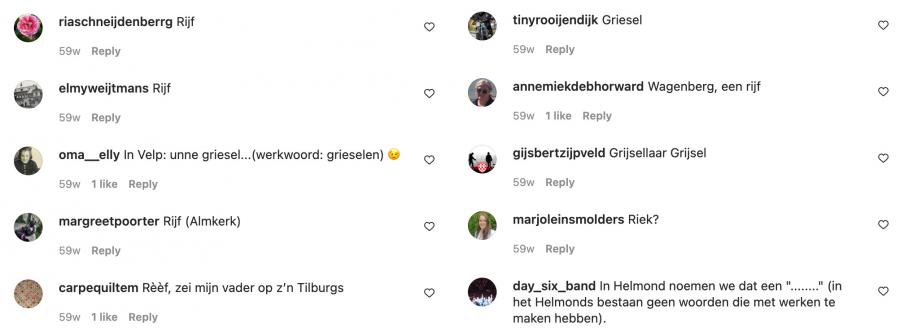

This screenshot shows an Instagram post of Brabants Erfgoed asking Brabantians which word their dialect uses for the word “rake”.

This screenshot shows a Facebook post of Brabants Erfgoed asking Brabantians which word their dialect uses for the word “jay”.

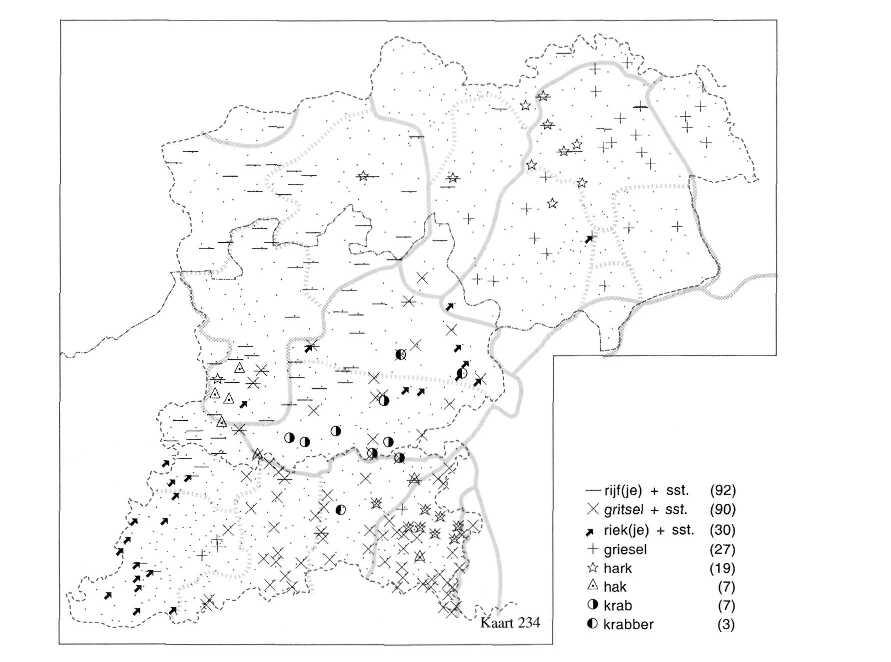

We posted pictures of agricultural subjects (barbed wire, rake, etc.) and birds and asked what they were called in our followers’ dialects. With the replies, consisting of the answers (dialect word) and placenames (localization of the word) we were able to compare the present-day situation of ethnolinguistic knowledge to earlier documentations, e.g., of data from the 1930s to 1960s from the databases of the Meertens Institute (Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences KNAW) in Amsterdam.

This screenshot shows some replies to an Instagram post about the word “rake”. Different words are mentioned and some additional information is shared, for instance considering the corresponding verb, pronunciation and a joke about a regional stereotype.

The results of these small inquiries were shared via social media and were or will be published on the website Brabants Erfgoed and in an edited volume of the Meertens Institute (Van Oostendorp & Wolff 2022).

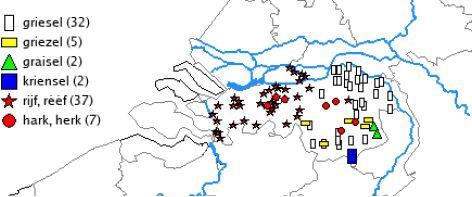

This map shows the different words that were used for “rake” between 1975 and 2000 (Woordenboek van de Brabantse Dialecten).

This map shows the different words that were used for “rake” in our most recent study, for which the Instagram account of Brabants Erfgoed and the social media of ‘Brabanders en hun taal’ were used.

This way we handed back the accumulated knowledge of these topics to the participants and made them part of this bidirectional online exchange of heritage participation. We made knowledge available for the online community by drawing upon the knowledge of the individual participants in that same community, which firmly empowered these small studies but also the interest of our individual participants.

‘Brabanders en hun taal’ connects a great number of people with shared interests in regional language and culture, offers ample opportunities to contribute and participate, and stimulates citizen science. The main goals of the new policy for regional language in Noord-Brabant have not been reached yet, but a first step has been taken; a growing online community of Brabantians displays its valuation for Brabantish on social media, and in doing so, contributes to the regional language’s preservation and development.

References

Blommaert, J. & P. Varis (2013) Enough is enough. The heuristics of authenticity in superdiversity. In J. Duarte & I. Gogolin (eds) Linguistic superdiversity in urban areas (pp. 143-158). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Cameron, D., Richardson, K., Frazer, E., Harvey, P., & Rampton, M. B. H. (2020). Researching Language. Taylor & Francis.

Ciolfi, L., A. Damala, E. Honecker, M. Lechner, L. Maye (eds) (2017) Cultural Heritage Communities. Technologies and Challenges. London: Routledge.

Oostendorp, M. van & S. Wolff (red.) (2022) Het Dialectendoeboek. De schatkamer van 90 jaar Meertens Instituut. Gorredijk: Sterck en De Vreese.