Birds Aren't Real: a post-truth 'conspiracy' paradox

Throughout the United States on billboards or on vans, the slogan “Birds aren’t real” is occasionally popping up. Birds Aren’t Real is a conspiracy theory claiming birds are not actually animals, but drone replicas installed by the U.S. government to spy on Americans (Birds Aren’t Real, 2021). This movement is linked with the conspiracy theory ‘QAnon’: a belief that the world is controlled by an elite cabal of child-trafficking Democrats. However, the Birds Aren’t Real movement is not real.

Birds Aren't Real: the conspiracy movement

In December 2021, the creator of the movement, Peter McIndoe (2021), explained to the New York Times the true meaning of Birds Aren’t Real. “It is a parody social movement with a purpose”: making fun of misinformation in a post-truth world dominated by online conspiracy theories (NY Times, 2021). Birds Aren’t Real is trying “to deal with the world of misinformation. A lot of people in our generation [Z] feel the lunacy in all this, and Birds Aren’t Real has been a way for people to process that.” (McIndoe, 2021)

While the movement's purpose is not to actually make people believe that birds are indeed drones, it does exaggerate its discursive actions. For example, on their website they answer the question ‘What is bird poop?’ as follows: “Confidential documents leaked in 2018 revealing that “Bird Poop” is actually a form of liquidated tracking apparatus. If you walk outside and notice some bird poop just “happened” to fall on your car, be aware that you are now being tracked by the United States Government.” Or to the question ‘What if ‘birds’ fly out to other countries?’, the answer is: “The government will do anything they can to maintain control over its citizens. Any bird you see flying across the U.S. borders is simply tracking an American citizen who went on vacation” (Birds Aren’t Real, 2021). The absurdity and hilarity in these small comments form the movements’ identity, and indexes the parodic intent of the entire Birds Aren't Real movement.

Surveillant landscapes

However, some people now truly believe that birds aren’t real. Indeed, big data and digital surveillance are concepts that are tied up with our everyday practices of searching the internet: from engaging with friends to online shopping (Jones, 2017). Birds Aren’t Real plays into this digital surveillance society and claims they “care that the government watches you drive to work, eat, and sleep. They see everything from above, without an ounce of consent from their own citizens” (Birds Aren’t Real, 2021).

It makes the powerless feel even more disempowered

Landscapes that are designed to make people’s actions visible and legible are known as surveillant landscapes (Jones, 2017). This landscape 'works' when it manages control over power relations: when it gives citizens the feeling they are being watched. A public space, which is by nature a surveillance space “built to maximize the exposure of people who inhabit them and thus minimize the opportunities for people to engage in antisocial behavior” (Jones 2017), would now also include drones with surveillance cameras if you believe Birds Aren’t Real. This visibility can make us feel safe (considering criminals versus government), just as it makes us feel vulnerable: it makes the powerless feel even more disempowered. The fact that environments are built to render behavior and identities makes people legible since these spaces are augmented by digital technologies that translate happenings into data.

What makes this digital surveillance possible has to do with the way discourse is deployed to lure users into making compromising decisions. Or, in the Birds Aren’t Real case, when drones are disguised as birds. Discursive processes can be divided up into participation, pretexting, entextualization, recontextualization, and inferencing (Jones, 2017). These processes impact the way we understand surveillance and force us to think of key issues in discourse analysis such as identity, agency, and power.

What Birds Aren’t Real complains about is the invisibility and lack of transparent communication by these surveillant landscapes (Birds Aren’t Real, 2021). Believing in the fact that detective cameras are covered by the appearance of flying birds is an example of a disguised practice of surveillance (Jones, 2017). The way these 'bird drones' fly over our heads is a form of monitoring through a panoptic structure to enforce a form of social organization and thus power relations (Foucault, 1970, p.132). “The situated interaction orders constructed by surveillant landscapes often act to invoke and reinforce broader cultural narratives about certain kinds of people and the kinds of relationships they are supposed to have: people such as criminals and victims, or citizens and their governments” (Jones, 2017). Bird-drones controlled by the government fly and observe, while humans are being watched and therefore controlled. This increases the feeling of disempowerment and the chances of distrust.

Regimes of post-truth

A lack of trust in the government brings us to regimes of post-truth, which are shifted from regimes of truth. The latter is a society that is characterized by truth markets, that correspond with a disciplinary society and tight functioning between media and education, scientific discourses, and dominant judgers of the truth (Harsin, 2015). In other words, regimes of truth are based on objective facts. Regimes of post-truth on the other hand are based on emotions. Harsin (2015) explains regimes of post-truth as societies of control “where power exploits new freedoms to participate and produce”. It emerges out of post-political strategies to control societies where resource-rich people attempt to use data-analytic knowledge.

The internet and social media have made post-truths, or counterknowledge, more accessible (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). In our ‘always on’ culture, algorithms play a big part in influencing people with predictive data, using surveillance to influence codes and software for quantifying digital behavior (Harsin, 2015). These algorithms create personalized filter bubbles, which happen when a user gets trapped by a search engine that collects user statistics, search histories, and click-baits, to keep providing similar information. At this moment, the user is shown no contrasting viewpoints on political or moral issues (Pariser, 2011). This has not per se led to the demise of truth regimes, but to a complex reorganization of functions to mobilize new digital participatory culture. This caused the rise of media misrepresentations, hoaxes, and conspiracy theories over the last 20 years (Harsin, 2006).

Conspiracy theory believers easily find each other as theories become easily accessible due to a 24/7 internet connection and alternative news channels or websites (Varis, 2019). Conspiracy theories take an ambivalent relationship to the truth and are based on feelings and identity rather than on facts. These kinds of theories are to be found on alternative news sites or counter-media outlets that promote ‘fake news’. Conspiracy theory, or conspiracism, is explicitly political in a populist fashion, as it posits that the common people are misled in secrecy by an elite group (Ylä-Anttila, 2018). These ‘fake’ theories provide a sense of security, as they explain the unexplained and comfortably fill a void for the lost searcher in place. Therefore, it becomes a populist theory of knowledge, with the assumption that ‘the truth is out there’: as the elites hold not just the secret power, but also secret knowledge (Ylä-Anttila, 2018).

Birds Aren’t Real (2021) critically states: “The government should not exist as a separate entity from the citizens - that is what a democracy is all about. We need to take this country back. You don't have to be a brainwashed sheep. Through the simple act of understanding that Bird-Drone surveillance is happening on a mass level, we slowly become human again.”

The socio-cultural and socio-political consequence of the division between conspiracy thinkers and non-conspiracy believers causes polarization in society due to the divergent disagreements (Sphor, 2017). This division is tangible in the offline and online nexus. More than ever before, we feel and notice our society's polarization as numerous Facebook groups, YouTube channels, and WhatsApp chats promote and organize protests to fight against the mainstream, as well as physical protests in metropolises. “So why not have fun with it?”, is Birds Aren’t Real vision statement.

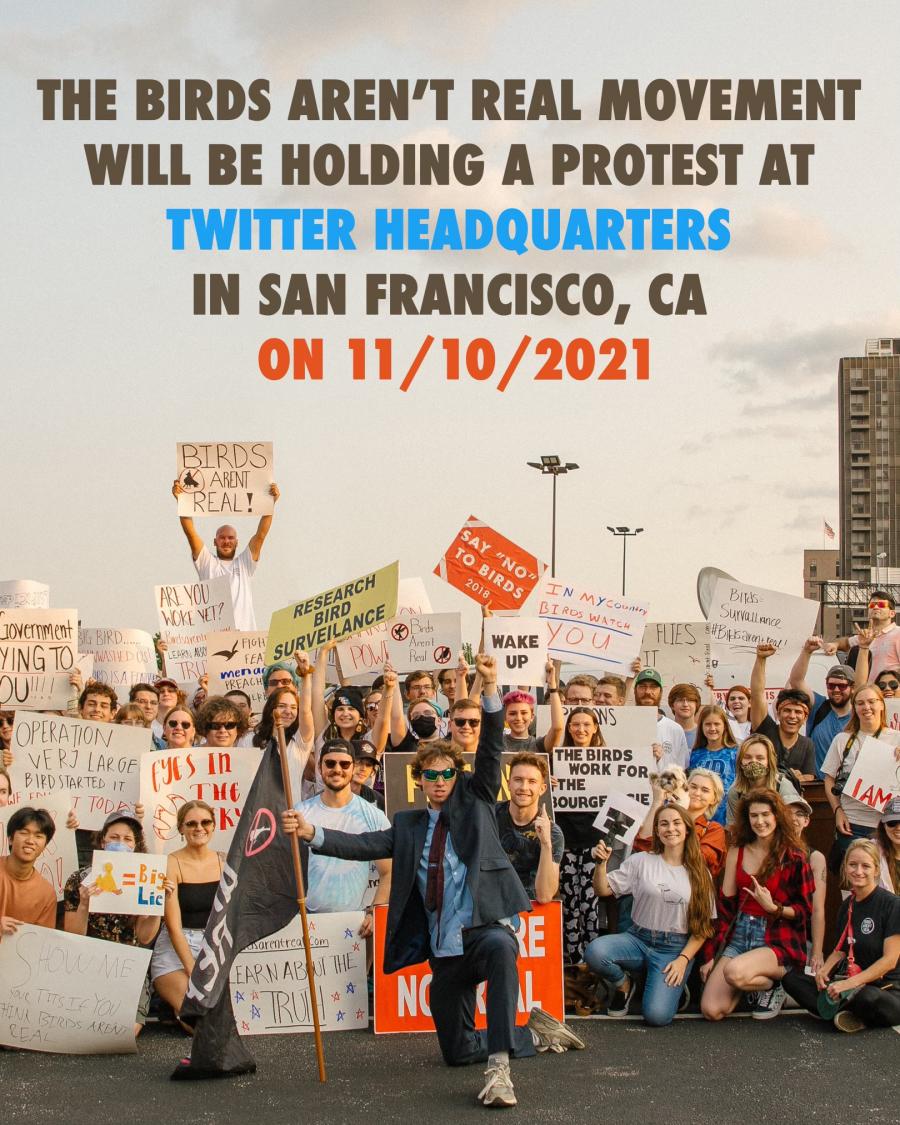

Figure 1: Picture of Birds Aren’t Real protest in front of Twitter HQ, demanding Twitter to change its bird logo

What Birds Aren't Real teaches us

It could be the case that this movement reminds you of the Flying Spaghetti Monster, which also began as a parodic religion and grew out into a social movement. It started as a protest against intelligent design alongside evolution in secondary schools. Similarly, the founder of Birds Aren’t Real explained to the New York Times (2021) how he was raised in a conservative and religious community, being home-schooled, and taught that evolution was a massive brainwashing plan by the Democrats. During High-School, the internet and social media offered a gateway as he taught himself different views of the world. “I was raised by the internet, my whole understanding of the world was formed by the internet.” (McIndoe, 2021)

He realized he was not the only young adult forced into multi realities and decided to reflect on the absurdity by founding Birds Aren’t Real – and so the experiment of misinformation began. This anecdote resembles the post-truth world, dominated by misinformation and surveillant landscapes in which most conspiracy theories are fueled by hate or distrust. This behavior based on emotions is typical for regimes of post-truth (Harsin, 2015). The Birds Aren’t Real movement on the other hand, is about “holding up a mirror to America in the internet age”. While it reflects on America’s post-truth society, it offers Generation Z a fun, viral-worthy, yet educational way of dealing with it.

References

Birds Aren’t Real. (2021). Birds Arent Real.

Foucault, M. (1970). The Order of Things. An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. Michel Foucault. Isis, 64(2), 246–247.

Harsin, J. (2015). Regimes of Posttruth, Postpolitics, and Attention Economies. Communication, Culture & Critique, 8(2), 327–333.

NY Times, T. (2021, December 9). Birds Aren’t Real, or Are They? Inside a Gen Z Conspiracy Theory. The New York Times.

Pariser, E. (2011). The Filter Bubble: What the Internet Is Hiding from You by Eli Pariser (2011–05-12). Tantor Audio.

Spohr, D. (2017). Fake news and ideological polarization. Business Information Review, 34(3), 150–160.

Varis, P. (2019, 10 november). Conspiracy theorising online. Diggit Magazine.

Venturini, T. (2019). From Fake to Junk News, the Data Politics of Online Virality. In D. Bigo, E. Isin, & E. Ruppert (Eds.), Data Politics: Worlds, Subjects, Rights. London: Routledge (forthcoming).

Ylä-Anttila, T. (2018). Populist knowledge: ‘Post-truth’ repertoires of contesting epistemic authorities. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 5(4), 356–388.