Capharnaüm: an engaging story about Beirut

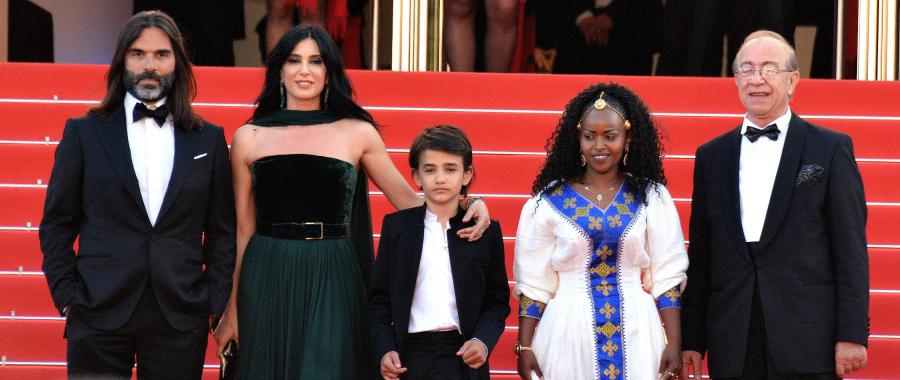

When the film Capharnaüm premiered at the Cannes film festival in 2018, it won the jury prize. The audience was impressed by its incredible and confronting story. Capharnaüm (“Chaos”), directed by Nadine Labaki, tells the story of Zain, a twelve-year old boy who wants to sue his parents for giving him life. He and his family are refugees from Syria, now living in Lebanon. Zain runs away from his parents because they have forced his sister into an arranged marriage. After running away, he is doomed to a life of crime and goes to jail.

The film is set in Beirut, where Zain wanders the streets trying to feed himself and a street baby named Yonas. Yonas has been abandoned by his mother Rahil, an illegal immigrant and could not take care of him anymore. Zain gets to know different people and is involved in heartbreaking situations, such being denied passage on a refugee boat because of his absent identity papers. "The film tells about the struggles of parenthood in a poor country, but told through the eyes of a twelve-year old child. It also tells about the refugee crisis and the importance of identity papers to prove that people actually exist." (Pomeroy & Rantala, 2018)

This paper explores the ways in which Capharnaüm makes these events believable to the audience and how they are affected. In doing so we will first go into Carphanaüm's place in the docudrama genre, and the consequences this has for the 'reality' of the film.

Then we will position Carphenaüm as a Third Cinema film, and further look at the different aspects of the film's impact on the audience, and how the events and characters that occurr can create emotional engagement. At the end we will come back to the issue of reality and fiction in Capharnaüm.

Capharnaüm as a docudrama

Capharnaüm can be seen as a docudrama. A docudrama, short for documentary drama, is a film genre where a fictional form is combined with documentary content. In Capharnaüm, the events illustrated have actually occurred but the form is like a fictional movie. This is different from an observatory documentary, where real material is shown, like archive footage and interviews.

However, in Capharnaüm, a lot of the Lebanese neighbourhoods are shown in their real state. It shows drone shots of the slums, with poor kids on the street selling things to make money. Another aspect of the documentary style in this film, however not the traditional observatory style, is that not everything shown in the film is really significant. We often just see how people are living to paint a picture of Lebanese life in the slums. In these moments, we do not see any events that have big effect on the story. This technique is called ‘a slice of life’.

“Docudramas are useful because they portray issues of concern to national or international communities, in order to provoke discussion about them.” (Lipkin, 2006) This film shows the poverty in Lebanon and the effects it has on families and especially children. Zain's individual story is illustrative of these particular issues. As the director, Nadine Labaki, mentions: “For me, film-making and activism are one and the same thing. I really do believe cinema can effect social change.” (Cooke, 2019) Provoking discussion in the audience is one of the most important functions of the docudrama, different from Hollywood films that focus on entertainment and making profit. Therefore, this film is related to Third Cinema, which is discussed later on.

How ‘real’ is Capharnaüm?

To provoke a discussion in the audience, there has to be something shocking or engaging in the film. In Capharnaüm there are different aspects that help to bring up a discussion. The most notable aspect is that the film is based on real events. After seeing the film, the audience may question the notion of realism. ‘Is this really happening? Or is it dramatised for the film?’ ‘Can we trust the story?’ To answer these questions we need to consider if the audience thinks it is a believable story. Is it a story that could have happened, or is it too obviously being dramatised?

Capharnaüm is made believable in different ways. For a start, the characters in the film are played by non professional actors who know about the real situation illustrated in the film. The audience may not notice this, but it is clear that the “actors” fit the story very well. “Zain Al Rafeea plays the character of Zain and is a Lebanese boy who at that time was staying illegally in Beirut.” (Beekman, 2019) So, he did not act, he was the character himself. This makes the “acting” more believable.

"Zain lives, in the film, with an illegal immigrant from Ethiopia, Rahil, for a while." (Cooke, 2019) Rahil is played by Yordanos Shiferaw, also an Ethiopian illegal immigrant. A street baby that Labaki found when she was observing the situation in Lebanon also plays a part in the story. “And for the character of Zain’s mother, the director was inspired by a woman who had had 16 children, seven of whom died from neglect." (Cooke, 2019)

"The anger of the children inspired me. Why did my parents conceived me, they said, if they do not care about me? That is not about poverty or about going to bed hungry. It is about the lack of love and care" (Nadine Labaki)

The events illustrated in the film are actually happening in Lebanon today. Director Nadine Labaki immersed herself in the world of the poorest children of Beirut for four years. She visited youth jails, detention centres and court proceedings. She became engaged and involved in the world of Beirut. She asked the children there if they were happy to be alive, and the answer was often ‘no’. She also stated: “The anger of the children inspired me. Why did my parents conceived me, they said, if they do not care about me? That is not about poverty or about going to bed hungry. It is about the lack of love and care.” (Beekman, 2019)

The ‘real’ Zain lived in a much more difficult situation than in the film, however, his parents do love him. So, some aspects in the film are made up, but always with the thought that it could be the truth. For example, the prosecution of the parents is fictional; it is not possible in reality to sue your parents for giving you life. But, if it was possible, these children would have done it. We can say that the events in the film are not dramatised to make it more beautiful. This is real and happening. The characters had almost no script and improvised along the way to achieve intense realism. This was possible because they know everything about their own lives.

Because of the absence of a script, it was a laborious project. "Nadine Labaki mentioned filming 520 hours of footage over six months." (Pomeroy & Rantala, 2018) Another example of achieving realism is that “when shooting the film, the mother of the street baby was arrested because of she was staying there illegally. What is fascinating is that in the film the street baby also loses her mother” (Beekman, 2019). When filming, truth and fiction were intertwined, which made it even more real and confronting for the director. Labaki knows the situation well because of her research and relation to the country, and thus the invented events in the film become real and truthful.

Capharnaüm as a Third Cinema film

Capharnaüm is a good example of a Third Cinema film. According to Dodge (2007): “The term ‘Third Cinema’ reflects its origins in the so-called Third World, which generally refers to those nations located in Africa, Asia, and Latin America where historical encounters with colonial and imperial forces have shaped their economic and political power structures.”

LeBlanc (2018) further says: “The films related to Third Cinema try to be socially realistic portrayals of life and emphasize topics and issues such as poverty, national and personal identity, tyranny and revolution, colonialism, class, and cultural practices.” The film shows the realistic life of Zain and the effects of his poverty. But we also see his personal and national identity and the meaning of this in his life. To add: “Third Cinema challenges viewers to reflect on the experience of poverty and subordination by showing how it is lived, not how it is imagined.” (Dodge, 2007) The technique, ‘a slice of life’, relates to this because it does not always shows big events.

Zain has many difficulties and setbacks in the film and this can be misleading in relation to the realism of the film. The audience might think that the film is dramatised, because everything is going wrong. First, Zain loses his sister because of an arranged marriage to a man he hates. He runs away and is left for dead. When he finds someone who can feed him, she leaves him with her baby. To make matters worse, he has to leave the baby for money for a boat he cannot even board because of absent identity papers. The film is a real drama and there is hardly any hope for a good ending throughout the whole film. However, the director did not choose to dramatise the events, but based these on findings of her field research.

"It is a tragedy of systems and institutions rather than of individuals." (Wilson)

The audience will be somewhat distanced from the story, because they are probably not as poor as Zain. When you think about this film premiering in Cannes, it is seen by (mostly) rich and famous people. And if you are not an immigrant yourself, you are probably not even capable of imagining these horrible situations. But this is a way of letting the audience know that it is happening and asking them to think about it, even if it is in whole other social class. It is good to think about the struggles of someone who is completely different from you.

Engaging the audience: sympathising with Zain

As seen before, the characters in the film play a huge role in getting the audience engaged with the story. The characters in this film are emotionally affected by the awful situations, which makes the audience personally engage with them, even when their background is completely different. The audience sees everything through the characters’ eyes and it is possible to think about the personal events that are happening. Batty (2014) states: ”It is through such characters that we experience media. It is through their perspective, point of view, and narrative drive—through agency—that audiences are able to follow what is happening.”

The characters in this film are emotionally affected by the awful situations, which makes the audience personally engaged with them, even when their background is completely different.

In Capharnaüm, Zain goes through a development, which we can also call a character journey. The attachment of the audience is structured in a way that guides them through identification with the characters. In this film, the development is an especially emotional development. As Batty (2014) states: "Physical action influences emotional development, and emotional development influences physical action."

An example of this development is that Zain’s sister Sahar forced into an arranged marriage to a man named Assad, who Zain hates. When Zain finds out, he is devastated and angry at his parents for letting their daughter go so easily. But for his parents it is an easy decision. With a lot of children to feed and no money to do so, this arranged marriage is a relief. So Sahar, even though she resists, is taken to Assad to marry him.

After running away, Zain needs to come back home for his identity papers. However, his parents do not have these and he finds out that Sahar is in the hospital. Apparently Sahar was pregnant but did not survive it, being only eleven years old. This is terrible for Zain and because of this emotional development, he is so angry that he stabs Assad with a knife. This circle of emotions influencing physical actions and the other way around is very visible in this film. Because of this, the audience can identify with his actions and emotions. They will understand his decisions and feel connected to him.

Zain has to overcome different obstacles and as audience you hope for the best.

"We need someone or something to guide us through the narrative — a central identification figure — we psychologically connect to the character as a way of rendering meaning possible" (Craig Batty)

Zain is the personification of these struggles and guides us through the story of poverty. The good ending of the film fulfils this hope, in a way. Zain finally receives his papers with a laughing smile on the front. But, the prosecution of his parents is just put into an archive with other, dozens of files. The audience is thus left feeling both relieved and disappointed. This mix of emotions, throughout the whole movie, pulls the audience into the story.

Wilson's (2014) description of the TV series The Wire can also be applied to Capharnaüm: "It is a tragedy of systems and institutions rather than of individuals." However, in Capharnaüm the tragedy of the individuals adds more emotion to the systemic tragedy. “Zain is actually not only suing his parents, he is suing the whole system because his parents are also victims of that system — one that is failing on so many levels and that completely ends up excluding people.” (Aridi, 2018) This adds a new layer to the struggles Zain has to deal with. He is the voice of all the children and families that are influenced by the refugee crisis.

Fiction and reality as a starting point for discussion

The docudrama Capharnaüm tells the story of Zain, who wants to sue his parents for giving him life. We see Zain develop throughout the film, especially on an emotional level. His emotions justify his (mostly) cruel actions. The audience identifies with him, because they know where he is coming from. It's a film about real events but told in a fictional form.

Even though there are a lot of wonderful aspects to realistic films, there can also be some difficulties. Lipkin (2006) explains: "Think about the permissibility, usefulness and even danger of mixing the functions of documentary and drama." When showing Capharnaüm to audiences in Lebanon, they reacted in two different ways. Part of them were shocked and moved by the discussion it had caused. However, the other partdenies the events illustrated in the film. "They do not want to look in the mirror and see the flaws of the country." (Cooke, 2019)

This shows that the message of the film is an important and good starting point for the audience to discuss these issues. But, mixing the functions of documentary and drama can mislead the audience in forming their opinion about the events illustrated in the film. They could misinterpret the message of the film. They will know it is not a typical documentary because of the form in which it is told. Considering that not everyone will immediately understand that these are real events, this movie can lose its value.

The film is not explicit about this realism by mentioning it before or at the end of the film. The audience has to think for themselves about this. But the confirmation of the real events illustrated is achieved by making it as ‘real’ as possible and using a personal and engaging story. On the other hand, trusting a film to be completely fictional is another difficult consideration.

Capharnaüm manages to mix the the functions of documentary and drama in a convincing way by making it so realistic that the audience cannot doubt it. The situation in Beirut was carefully researched, something audiences can verify with a quick google search. The story is constructed through facts. This makes Capharnaüm a good starting point for discussion of the issues illustrated, and it will affect the audience in a positive, engaging way.

References

Aridi, S. (2018, December 16). Capernaum Is Not Just a Film, but a Rallying Cry.

Batty, C. (2014). ’Me and you and everyone we know: the centrality of character in understanding media texts. In B. Thomas & J. Round, Real Lives, Celebrity Stories: Narratives of Ordinary and Extraordinary People Across Media (pp. 35–56). New York, United States: Bloomsbury Academic.

Beekman, B. (2019, January 30). Regisseur Nadine Labaki: ’Misschien zorgt Capharnaüm ervoor dat er in ieder geval eens over deze kinderen wordt gepraat’

Cooke, R. (2019, February 25). Nadine Labaki: ‘I really believe cinema can effect social change’.

Dodge, K. (2007, January 11). Third (World) Cinema: What is Third Cinema?

LeBlanc, J. (2018, November 26). Third Cinema.

Lipkin, S., Paget, D., & Roscoe, J. (2006). Docufictions: Essays on the Intersection of Documentary and Fictional Filmmaking. In G. D. Rhodes & J. P. Springer, Docudrama and MockDocumentary: Defining Terms, Proposing Canons. (pp. 11–26). Jefferson and London: McFarland and Company.

Pomeroy, R., & Rantala, H. (2018, May 18). Tipped for Cannes glory, Beirut slum actors play their real lives.

Wilson, G. (2014). “The Bigger the Lie, the More They Believe”: Cinematic Realism and the Anxiety of Representation in David Simon’s The Wire. South Central Review 31(2), 59-79. Johns Hopkins University Press.