The power of online reviews in decision-making

In our daily lives, we make decisions based on the experiences of others, often online. We may trust reviewers blindly on their expertise and knowledge on films and books. This is caused by the emergence of social media, which has resulted in people discussing with others around the world all kinds of topics, from politics to experiences in daily life. This urge to discuss issues online is visible in the availability of many websites that focus on reviewing different products and services. For example, the reviewing of places, like hotels or restaurants. Entertainment objects are also reviewed, including films and books. These reviews involve the sharing of one’s experience of a cultural object. On websites that focus on the sharing of reviews, like IMDb, the biggest film-rating website, users create the content for the website’s reviewing section.

Visiting these (partly) user-generated websites is embedded in our daily lives. Whenever one is searching for a film to watch or one just has watched a film, one can retrieve information about the quality of the film by reading reviews. A decision to watch a film can be made or an opinion constructed after watching the film, based on the subjective experiences of others. But which reviews are seen as trustworthy? How do these platforms contribute to what users regard as experts and knowledge online?

Experience as evidence

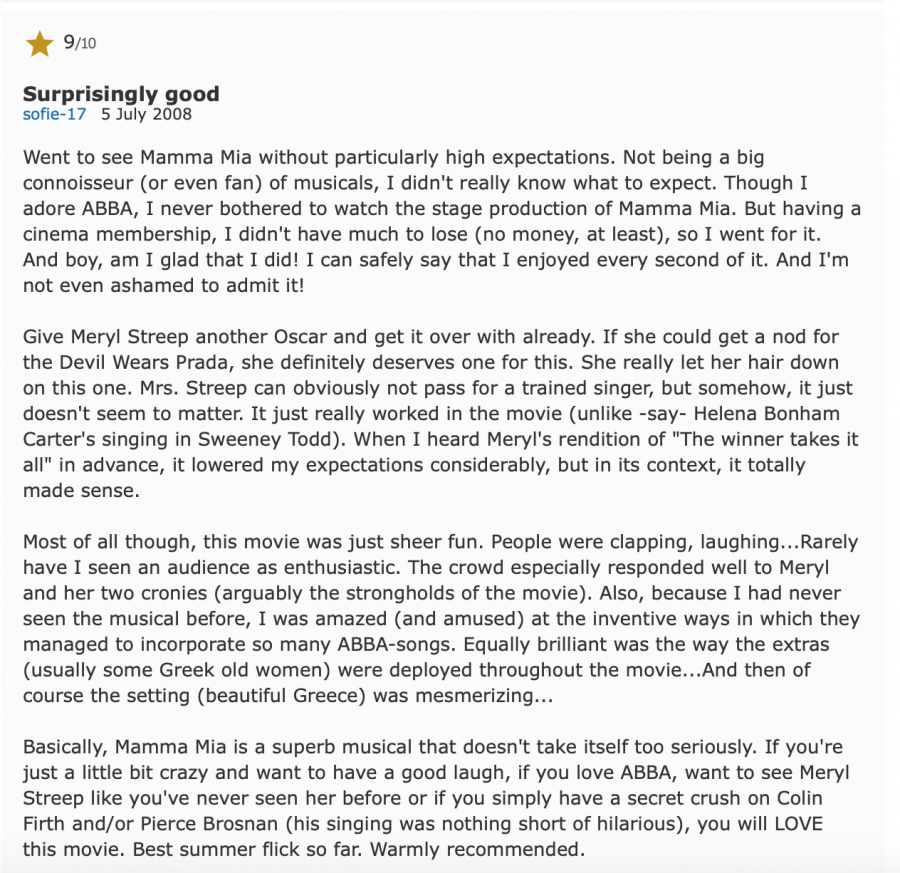

First, it is important to clarify some things about the relation between experience and knowledge. Personal experience is one source of knowledge. Experience is socially constructed, and it depends on the context in which it occurs (Scott, 1991). Individual interpretations of a situation can therefore also differ from person to person. For instance, one person can find the film Mamma Mia! (2008) very cheerful and romantic, while someone else finds it too cliché. These experiences depend, among other things, on what your taste in films is, on your age, your knowledge about films, what films you have seen before, and so on. Every individual focuses on different things when rating a film. The reviews of Mamma Mia! on IMDb show a great variety in ratings. Two different users, for instance, both mention their love for ABBA but rate the film totally differently. These two reviews show how experience is always a matter of interpretation. One user focusses on the actors and how the audience responded to the film in the cinema, while the other focusses on the colours used, the singing and the plot.

Entextualizing experiences

Users contribute to the discourse with the entextualization of their experiences (Hanell & Salö, 2017). In other words, they put their experiences into words for others to understand them in the context of an online review. As Scott (1991) has argued, "writing is reproduction, transmission - the communication of knowledge gained through experience" (p. 776).

Users of IMDb who look for reviews after they have watched a film, will be pointed in different directions regarding the quality of the film. However, when you have watched the film and think it is really good, you will probably agree with the good reviews. It works as a "self-fulfilling prophecy", where the outcome depends on the things you filter out of all the reviews. People tend to rely on shared norms, references, and understandings, and therefore, the reviews that one agrees with are seen as evidence that their opinion is correct. However, every experience is still an interpretation. As Todd VanderWerff, culture editor at Vox.com, has said, "I feel like [movie rating websites] have created a sense that there’s an answer to whether a movie is good or bad when really that’s a very personal question" (Hickey, 2017). As experience is seen as evidence, anyone can become an expert on cultural knowledge by writing user reviews.

Algorithms and the orders of visibility

Other factors also contribute to one reviewer’s expertise compared to another's, such as the use of algorithms, which are embedded in every medium and thus everywhere in our society. Algorithms are now "a key logic governing the flows of information on which we depend" (Gillespie, 2014, p. 167). They have the "power to enable and assign meaningfulness and manage how information is perceived by users", a concept which Langlois (2013) called the "distribution of the sensible" (as cited in Gillespie, 2014, p. 167). Algorithms thus play an important part in our social lives.

Reviewing websites also use algorithms in order to sort reviews. Companies thereby make, with the use of algorithms, decisions for the users, for instance, through recommendations. On the book reviewing website Goodreads, users will get recommendations based on the books they have clicked on before, or because they like a particular genre. The website’s database contains all kinds of data about the users’ behaviour on the site. The algorithms then decide what data is useful to use as input and what should be showed as relevant. Still, relevance is an interpretation of what is useful for the user to see and is always designed with certain ideas in mind regarding what is relevant. Relevance is decided based on other information, like follow-up clicks on the things recommended (Gillespie, 2014).

Algorithms are now "a key logic governing the flows of information on which we depend" (Gillespie, 2014).

The algorithms also decide what numerical rating a film receives. This can be the true average of all the ratings given, or the mean, or even only the average of “real” critics. IMDb offers an average on a scale of one to ten, where it does not matter if everyone gives a 7,5 or if the ratings are different but average to 7,5. However, they tweak this a bit with the use of algorithms that prevent certain groups from disproportionately influencing the vote (Reynolds, 2017). Rotten Tomatoes, another website for reviewing films, only uses reviews from critics to make up an average score. In addition, it weighs its rankings depending on how many reviews a film has (Reynolds, 2017). These differences in algorithms may make users prefer one platform over the other, although these algorithms can also change every day.

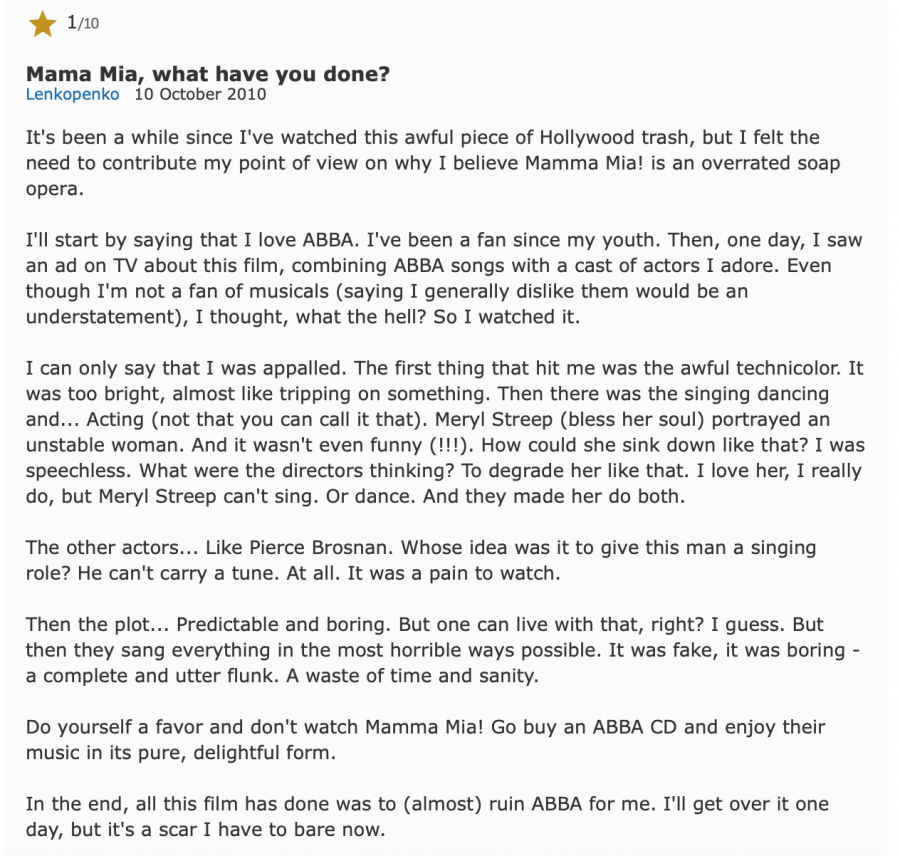

Algorithms on these kinds of websites also decide the orders of visibility (Hanell & Salö, 2017). The reviews that are most engaged with or clicked on, will be listed on the first page. The placement of a review on the first page results in more visibility and will make it more likely for the first-page review to be seen as more credible than a review on the last page. The algorithms normalise this cultural knowledge logic as “right” (Gillespie, 2014). The platform makes these reviews suitable to be employed as knowledge (Hanell & Salö, 2017). However, the review’s placement is not related to its truthfulness, but only related to the amount of engagement and other aspects that the algorithms decide. On IMDb, every review can be rated by readers. A voting system also influences the order in which the reviews are placed on the website. So, readers can decide when a review is helpful or not by voting. When a review is found to be helpful, it gains more visibility for users than a review that only a few people found helpful. The algorithms are thus producing and certifying knowledge for users of the platform, in collaboration with humans.

In addition, users can learn how to write a “helpful” review that receives a lot of positive feedback. As Gillespie (2014) explained, "we make ourselves already algorithmically recognisable in all sorts of ways" that are sometimes not even explicit (p. 184). When using a platform a lot, the requirements for users to like a review can be learned. For example, the length and depth of the review can be taken as an indication of it being "helpful". Or, users may adjust their review to the numerical rating of the film and write a review that fits this widely shared opinion.

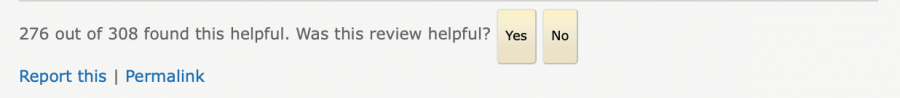

On Rotten Tomatoes, the orders of visibility are clear. Only four reviews are visible on every film page. On Rotten Tomatoes, this visibility depends on whether you are a “super reviewer” or not. According to the website, super reviewers are “users who’ve demonstrated consistent insight and whose reviews we feature prominently on film pages” (Rotten Tomatoes, n.d.). In other words, the website has some kind of system to decide who is featured and who is not. This shows that every review website has a political aspect to it, in the sense that there is always power involved regarding who decides which experience is worth relying on.

'Joker' highlighted reviews

The power of the platform

When one analyses this platform further, it seems that Rotten Tomatoes has all kinds of reviewers. They also distinguish Verified Reviewers, Super Reviewers, Critics and Top Critics. This way, they also draw a line between normal users and professional critics. Critics are podcasters, newspaper and magazine writers, bloggers, and YouTubers, according to the website (Rotten Tomatoes, n.d.). These so-called “critics” are not very different from normal users, as they all use their interpretation to say something subjective about a film. It is very possible that a critic knows more about cinematic features and cinema in general. With the platform legitimising their knowledge, these critics have more power over what is considered as legitimate knowledge compared to other users (Hanell & Salö, 2017). However, a film that is negatively criticised by "critics" a lot can still be a very good film to watch for different individuals.

Every platform has different kinds of users and thus every platform is biased in a different way.

The power of these websites goes even further, beyond the shape of the platform itself. Users also play a role in the kind of power the platform has. Every platform has different kinds of users and thus every platform is biased in a different way. For example, the users of IMDb are mostly men; "men often make up over 70 per cent of the voters for any film" (Reynolds, 2017, par. 21). This has consequences when searching for the rating of a film on IMDb because "men consistently rank masculine films higher than films that feature female leads or more traditionally female themes" (Reynolds, 2017, par. 24). The same applies to Rotten Tomatoes, which has a vast majority of male critics.

Trusting reviews

Then there is the notion of fake reviews. It is hard and very time-consuming to discover fake reviews as a user, even though they can of course influence what is seen as knowledge or evidence of, for example, the quality of a product. For instance, this happens on Amazon, where the seller can leave a review of his or her own product with a different name. This also counts for websites like IMDb, which is owned by Amazon, where a cast member of the reviewed film can write a very positive review in order to promote the film and to get more buys on Amazon. In addition, with online reviews, there is no evidence that the reviewer has even watched the film reviewed. Readers thus have to trust the reviewer to be honest, something that is always the case with user-generated content. Some websites, like Rotten Tomatoes, avoid this blind faith by letting their users give evidence. Rotten Tomatoes has, for instance, “Verified users” that upload their cinema ticket together with their review. This is still of course no guarantee that the review is based on honesty but images as evidence are seen as more credible than words. The cinema ticket can therefore be taken by the audience as visual evidence of the reviewer’s honesty.

Shaping culture experts

To conclude, the construction of experts on cultural knowledge online is influenced by various factors. It is determined both by the users itself and by the platform. Platforms can decide what is more and what is less visible to visitors using algorithms. This is because the platforms’ rating systems do not show a neutral selection; they show what they want visitors to see. When users know of the workings of the algorithms, they can manipulate them in order to gain more visibility. Users can then write reviews that will be liked and engaged with more, and thus become more visible on the platform. Algorithms are therefore not only shaped by their engineers, but also by their users. However, we can never really know the true procedures behind the algorithms unless they are openly explained. These unknown procedures can be tricky, because algorithms that make decisions for us can of course feature failures and mistakes.

In addition, the readers of reviews still have their own opinions and can decide what counts for them as valid knowledge and what doesn't. This also depends on different social factors, like the environment you grew up in or the kind of friends you have. It is best to just watch or read what you want to, instead of making your decision based on others’ interpretation. Everyone can be an expert if it is about an interpretation, so why not trust yourself? However, even when you trust others’ reviews, the only thing that can go wrong is watching a film or buying a book you do not like. And how bad is that really?

References

Gillespie, T. (2014). The relevance of algorithms. In Gillespie, Tarleton, Pablo J. Boczkowski & Kirsten A. Foot (eds.), Media technologies: Essays on communication, materiality and society (pp. 167-193). MIT Scholarship Online, 167-193.

Hanell, L. & Salö, L. (2017). Nine months of entextualizations. Discourse and knowledge in an online discussion forum thread for expecting parents. In, Kerfoot, Caroline & Kenneth Hyltenstam (eds.), Entangled discourses. South-North orders of visibility. London: Routledge.

Hickey, W. (2017, April 21). Be Suspicious Of Online Movie Ratings, Especially Fandango’s.

Reynolds, M. (November 10, 2017). You should ignore film ratings on IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes.

Rotten Tomatoes. (n.d.). FAQ. Retrieved from https://www.rottentomatoes.com/faq

Scott, J. W. (1991). The evidence of experience. Critical Inquiry 17(4), 773-797.