Doxing and online communities

Doxing is proof that the internet is as real as the offline world. Imagine that someone goes through the internet and tries to find every personal detail about you. Where you live, where you work, the names of your family members and your telephone number. This person might not be alone and fires up an online community to track you down. This is what happened to Zoe Quinn, a female developer in the gaming industry. She became the center point of online harassment in what was later known as ‘Gamergate’. After a blogpost of her ex-boyfriend was posted where she was accused of cheating, random internet people joined forces to discover all her personal details. Her information was published and harassment followed.

This phenomena, called doxing, has become a problem in an increasingly global world with increased connectivity and networks spread out over the globe. This article aims to research doxing and online communities, and how the latter facilitates the former in a global context. To answer this question, current literature and trends will be analyzed and specific doxing cases will serve as examples throughout.

Doxing

Doxing comes from ‘dox’, which is a play on the word ‘documents’. It is the act of tracing someone or gathering their information, hence the word ‘documents’. The image below illustrates from which sources these ‘docs’ can be retrieved. Information can be found in a lot of different areas of the internet, from local news websites to personal profile pages on Facebook and Twitter. D

oxing sometimes involves hacking, such as trying to retrieve someone’s IP address to find out where they live or work. The success of the dox is entirely dependent on the ability of the doxxer to find information, assess its relevance and combine the bits of information in order to find out more about this person’s identity. Now, the next step is very crucial and arguably the most harmful. The collected information, ‘dox’, about the person’s identity is shared online. But why would someone do this? And at what cost?

Doxing

Online vigiliantism

When you go through the history of the internet, you may notice there is a vast array of known doxing cases that each seem to serve a different purpose. Unfortunately there are countless examples of doxing. There is, understandably, huge debate over the act of doxing and the causes it is used for. While some cases can be quite personal, and only serve the vengeful need of the doxer, other cases are different and more serious. With the concern of society at stake, doxing can be used to organize an online witch-hunt for a person that is believed to have committed a crime.

The action of taking the law into one's own hands to effect justice is definitely not new. Vigilantism is something that people have done all throughout history, fighting crime with their own beliefs on what is wrong and right. However, the information technology of contemporary globalization has brought about new dimensions.

Online vigilantism relates to a public that unites on virtual networks and puts in a joined effort, or crowdsources, in order to find justice. It is what happened after the Boston Bombing in April 2013. A 22-year-old Brown University student Sunil Tripathi was the target of an online manhunt. The student went missing in March 2013, before the bombings in Boston happened. In the light of this event a thread was started on the popular social network Reddit, on a subreddit called r/FindBostonBombers. The community went through the internet comparing information released by the FBI with pictures, videos and other types of information.

Even a large network such as CNN can be found guilty of doxing. That seems to be a characteristic: everybody can dox.

They ended up wrongly identifying Sunil as the bomber. The Facebook page set up in an attempt to find Sunil after he went missing was flooded with hate comments. Unfortunately, it happens often that someone is wrongfully identified. Unfortunately, in the mass of communication that is the internet, there is not always time and space for fact-checking. If you happen to share similarities with a culprit, or if a bunch of internet strangers are convinced you did something wrong, that could be enough to get you doxed.

A very similar phenomena with a different name is the ‘human flesh search engine’ in China. It is basically the same deal, people (sometimes wrongfully) accuse a person of a certain crime. This can range from adultery to the abuse of animals. The phenomena first came into the picture when a video went viral of a woman wearing stiletto heels and using these to crush a kitten’s head. People on the internet joined forces to find out who this woman was, and made her pay for it. After her identification she lost her job and received numerous death threats.

In a different case, a certain Mr. Yin was wrongfully accused of spitting on an elderly homeless man. The scary thing is that the harassment continues offline. Mr. Yin received many calls every day with serious threats, his house would be burned down if he didn't pay the threateners. And while most threats on the internet are empty, in this case it can quickly become very real. The consequences can be huge for individuals. Online anonymity is exchanged for offline harassment. Therefore doxing should not be taken lightly.

The ethics of doxing are debatable. While the manhunt on Sunil was done arbitrarily by a large group of individual anonymous internet surfers, there are also systematic doxers. The hacktivist group Anonymous is known for outing several people and organizations. Usually this involves big, political actions against people like Donald Trump or the Islamic State. There seems to be a trend of activism doxing.

If doxing involves tackling a large institution or a threat to a harmonious society, the general consensus is probably that this is OK. There is an inflation of cases where doxing is used to publicy name and shame individuals that are believed to have misbehaved in one way or another, such as the doxing of Nazis from the Charlottesville's rally.

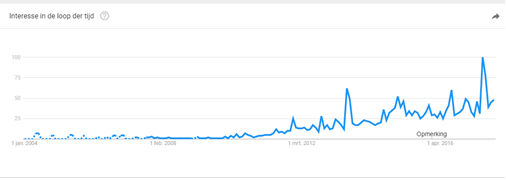

A search in Google Trends shows that the popularity of the name has increased significantly since 2004.

Google results show many different hits with information about doxing and, strikingly, simultaneously shows information on how you can protect yourself against doxing. What can be done against doxing? Doxing in itself is not illegal, as long as it solely contains publicly shared information. However, it can take a turn for the illegal if the information is used to stalk, harass, steal identity, blackmail, etc. It causes controversy, as people who are accused of doxing point to the availability of the information. However, most people can agree that instigating harassment cannot be tolerated.

Online communities such as Reddit and 4chan, while not aimed at doxing specifically, seem to be perfect platforms for instigating online man hunts. At odd times, these networks are put to work to find the love of someone's life.

As it turns out, even a large network such as CNN can be found guilty of doxing. That seems to be a characteristic: everybody can dox. Of course, as mentioned before, success in finding information depends on the ‘skills’ of the doxer. Then again, using an online network to receive help from other people clearly improves your chances of finding relevant information, of which the community focused on doxing and online vigilantism WeSearchr is a prime example.

Online communities in global networks

As mentioned before, the information the doxxer gathers about the victim mostly comes from online communities and networks. While the definition of an online community is not clear, it seems that the following definition is fitting: "a group of people, who come together for a purpose online, and who are governed by norms and policies" (Preece, 2000).

Online communities are quintessentially global. As Castells (2010) mentioned in his book The Rise of the Network Society:

“With the prospects of expanding infrastructure and declining prices of communication, it is not a prediction but an observation to say that on-line communities are fast developing not as a virtual world, but as a real virtuality integrated with other forms of interaction in an increasingly hybridized everyday life.”

In other words, the aforementioned networks are effectively part of our everyday lives. It is hard to imagine a world without them and quite frankly, they are hard to avoid. It seems that everybody is using these networks. Consequently, people are connected through these networks 24/7.

Communities are formed everywhere, as it is easy to bring people together online around shared values and interests. An online community can concern games, hobbies, socializing, news, opinion, anything. There are a number of social networks that have penetrated fairly well into society considering the number of users. Think of social media such as Facebook, YouTube and Instagram that have respectively 2.061, 1.500 and 700 million users. By looking at them, it seems they all mainly involve a personal profile, private messaging and data such as pictures and videos.

Thus, nobody can refute the growth of social networks in the last decade. People participate in these communities around a plethora of values, interests, passions, or whatever you want to call it. There are many networks devoted to rather general shared interests such as ‘being a parent’ or 'being a student'. But even people that enjoy eating ice, or have an interest in Thomas the Tank Engine’s soundtrack remixed with hip hop songs, can find like-minded people online. This shows that people will find and identify with each other over the most arbitrary shared interests. More importantly, it creates a community feeling, a sense of belonging.

In community psychology McMillan & Chavis (1986) describe four factors that together can create a sense of community: membership, influence, integration and fulfillment of needs and shared emotional connection. While it is unnecessary to go into too much detail about the psychology of communities, we can point to the influence factor that communities have on its members and vice versa. Additionally, Morgan et al. (2011) compare traditional media to social media and list several characteristics. It seems that a combination of the reachability, accessibility and immediacy of social media can facilitate doxing. Social media have an extensive reach and are accesible for free or very low prices to anyone in the world with an internet connection.

Another factor Castells (2010) points out that seems to fit here is the space of flows. The success of these global communities is that they transcend spatiotemporal limitations. Regardless of location, people are able to participate in online networks at any given time of day. Information moves at a very high speed across the globe. This is what makes the term ‘viral’ so relevant. In relation to doxing this means that information about people can be found at any given time of day, from any location in the world. Information flows freely between networks and is highly available.

Moreover, the community feeling that is established in these online networks facilitates doxing in two ways. Firstly, they create a platform for inciting people to dox. People might adhere to this because they sense they belong and want to remain part of this community. It might be the case that if your community tells you that is OK to harass someone, people will follow this example.

Secondly, the communities create a sense of trust. With trust, people might feel more comfortable sharing private information. They might feel that they are in a 'safe space'. This brings us to our next point; information sharing in these online communities.

Information sharing

A characteristic of many of these online communities is that people are encouraged to share information online. Facebook wants to know where you work, where you go to school, where you are now etc. These are all very personal details. The success of doxing is the availability of this information. What has been put online, usually stays in the ether forever. This puts pressure on the responsibility tasks of social networks in protecting this information. A recent court case cleared Facebook from the claim that they violated the privacy of 25,000 people.

Many researchers have been engaged in studying the information sharing behaviour of users in the virtual world. Privacy regulations on network websites have received a lot of attention. If you ask people blatantly if they are willing to share their very personal information with you right now, they are reluctant. Why does this changes when they are surfing the web? People are leaving bits and pieces of numbers and addresses everywhere for websites and commercial organizations to pick up on. While this at worst would be a nuisance, people are generally not aware this could lead to actual harassment.

Many different social networks propose different privacy settings. People are often not aware of what can be found online. On Dumpert.nl, a video shows an act where people are lured to a 'fortune teller' that seems to get a lot of the details a little too perfectly right. The availability of information is crucial in the act of doxing. With well-protected profiles and low visibility in the virtual world, doxers are lost. Instead, with an accumulation of communities and networks people are part of and varying degrees of privacy affordances, people leave bread crumbs everywhere for doxers to pick up on. One piece of information leads them to the next.

Doxing as a side-effect of globalization

Doxing can be viewed as a side-effect of globalization. Networks are expanding and people are connected globally, every moment of the day. The information that is shared in these communities or networks is saved forever and accessible to anyone. People might not be aware that the small bits of personal information they leave behind can haunt them in their offline life.

Online communities are enriching offline networks and a combination of these two can be disastruous for doxed victims. Communities are used to crowdsource information about people. Doxing is growing in popularity and it can have incommensurable consequences. With increasing connectivity and accumulating data and communities: where will it end?

References

(2017, December 17). Retrieved from WeSearchR.

(2017, November 23). Retrieved from Statista.

(2017, December 17). Retrieved from Parenting.

(2017, December 17). Retrieved from The Student Room.

(2017, December 12). Retrieved from Ice Chewing.

(2017, November 3). Retrieved from Google Trends.

(2018, January 2). Retrieved from Anonymous.

Anonymous - The TRUTH about Donald Trump. (2017, January 28). Retrieved from YouTube.

Castells, M. (2010). The rise of the network society. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Charlottesville Doxxing. (2017, August 14). Retrieved from NY Times.

Collins, K. (2017, November 14). Facebook safe from massive privacy lawsuit for now. Retrieved from CNET.

Doxing. (sd). Retrieved from www.html.com.

Doxing at it's finest. . (2011, December 29). Retrieved from Imgur.

Ellis, E. G. (2017, August 17). WHATEVER YOUR SIDE, DOXING IS A PERILOUS FORM OF JUSTICE. Retrieved from Wired.

Fremlin, D. J. (2017, December 17). Identifying Concepts That Build a Sense of Community. Retrieved from Sense of Community Research.

Gedachtelezer laat zien hoe het werkt. . (2017, December 17). Retrieved from Dumpert.

Hatton, C. (2014, January 28). China's internet vigilantes and the 'human flesh search engine'. Retrieved from BBC.

Hern, A. (2017, June 17). Islamic State Twitter accounts get a rainbow makeover from Anonymous hackers. Retrieved from The Guardian.

Lee, T. G. (2015, June 22). The Real Story of Sunil Tripathi, the Boston Bomber Who Wasn't. Retrieved from NBC News.

Malone, N. (2017, July 26). NY Mag. Retrieved from nymab.com.

Morgan, N., Jones, G., and Hodges, A. (2011). Social Media. The Complete Guide to Social Media From The Social Media Guys.

Shugerman, E. (2017, July 5). CNN accused of blackmailing Reddit user behind Trump's wrestling meme. Retrieved from Independent.

Subreddit How to Hack. . (2018, January 2). Retrieved from Reddit.

Thomas The Dank Engine. (2017, December 11). Retrieved from Reddit.

Vigilantism. (n.d.) West's Encyclopedia of American Law, edition 2. (2008). Retrieved January 2 2018