Empress Theodora: A feminist at the dawn of the Middle Ages

Empress Theodora of Byzanthium is mostly known for her early years, which she spent in poverty. However, if we look at the rest of her life, we can see an early medieval example of feminism in her actions as empress.

Who is Empress Theodora?

The lone ponderer’s senses will be delightfully nourished when they find themselves in the Basilica of San Vitale, an early Roman Catholic church located in Ravenna, a small port city in north-eastern Italy that is often described as “the capital of mosaics”, due to the superb medieval artworks that decorate many of its archaeological sites. While the eyes enjoy this aesthetic miracle, a vigilant mind may unexpectedly come into great surprise while encountering a strange discord between the age that the church has been built in, the 6th century AD, and two of its most luminous mosaics. One of emperor Justinian and that of his wife and empress, Theodora, which both adorn the apse’s opposite side walls.

"Byzantine images do not simple illustrate; they also encapsulate ideology" argues Liz James (2001). And by reflecting on this, what raises a few eyebrows is the fact that both central figures of these mosaics are symmetrically displayed opposite each other, being identical in height, size, and embellishment, showcasing thus overtly, as LeBel and McLaughlin state, gender equality between them, and connoting that the empress' role has been equivalent to that of the emperor's regarding the governance of the empire.

But who is Theodora and why is she that important?

Her name serves as a good reason to go back to the very early stages of feminism and to shed light on her historical figure. She was someone who, as J.W. Barker (1966) writes, “clawed her way up from a life among the dregs of human society to the peak of human ambition”. Moreover, her contribution to the amelioration of the status of women in society has been considered so valuable that it led the highly prominent Byzantine scholar Charles Diehl (1979) to describe her as 'deeply feminine'.

A 'rags to riches' story and a portrait in question

Before rising to the throne of the Byzantine Empire, Theodora’s life had been a diametrically opposite one. Her beginnings are described by Austin (2010) as 'exceedingly humble', as she was born into a circus family and grew up in the society of the Hippodrome of Constantinople. Her father’s early death led her to become an 'actress', a term that, as Gregory (2005) states, "is synonymous with a prostitute in modern day" and to live a life of sexual immorality.

The events that mark this period of her life were first described by Procopius of Caesarea, the most eminent historian of the age. His Secret History, a scandalous narrative that has received universal credence, has been the main source of the life events of the uncrowned Theodora and one that resulted in her utter denigration. In it, Procopius uses the boldest terms to discuss Theodora. As Lankila (2008) states, he was influenced by both the ideas in society surrounding members of the lower classes and preexisting unfavorable views of women. As a consequence, what is ascribed to her is a lascivious status and a life so depraved it was unparalleled. To understand how harmful these texts are, one could argue that C.E. Mallet's (1887) statement that "from the date of the publication of the Secret History, Theodora was condemned" aptly describes the degree of tarnishing that her name suffered.

But is this the Theodora that we shall remember?

Many of the events of her later life are less well-known. Theodora's life took a wholly different trajectory once meeting Justinian. Through their marriage, which took place after the institutionalization of a special law, as it was illegal for men of senatorial rank to marry courtesans, she was moved up to the uppermost position in a class-conscious society. Her part has been essential to the expression of her husband's imperial role. This provided her with the ability to exercise political power. Consequently, she occupied an exceptional position of influence upon political matters, as Vasiliev (1958) informs us, and her opinion had to be taken into account in the emperor's decision-making.

However, Theodora's rise to the throne did not make her forget where she came from. Her first-hand experience of the evils that lower class women could face turned her into a woman of great philanthropy, who lavishly provided a helping hand to those living in thrall of the strictly patriarchal and misogynist society of Byzantium (James, 2009). To paraphrase Diehl (1905), one could argue that her feminist spirit was based on the following phrase from Virgil's Aeneid (29-19 B.C.; 2008): “No stranger to misfortune myself, I have learned to receive the sufferings of other”.

Hence, it would be prudent not to judge Theodora to such a harsh extent in relation to the ethics of her early life. It would, however, be constructive to sketch a portrait based on her charity.

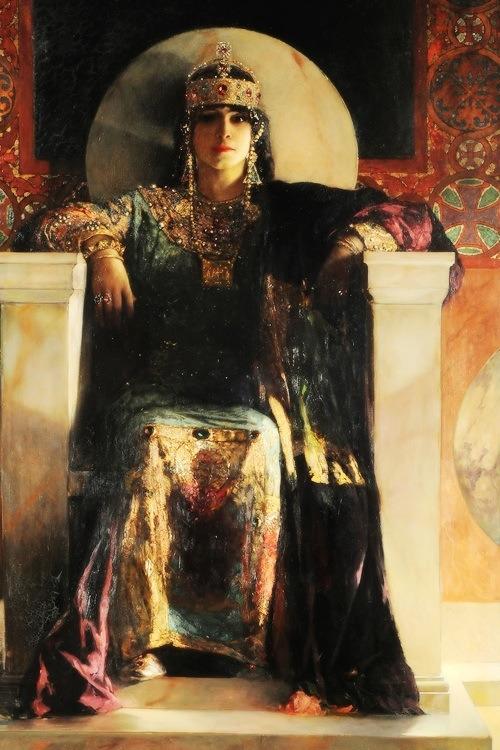

© Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant

An Advocate for women

© Jean-Joseph Benjamin-Constant

An Advocate for women

Lynda Garland (1999) mentions that "much of Justinian’s legislation was concerned with protecting women and their rights”. Of course, even back then, violence against women and girls, was a global phenomenon was been hidden, ignored, and accepted. Theodora was aware of that, and therefore aimed to make an effort in their favor. Her influence regarding many reforms and legislations concerning the status and the protection of women, though latent, has been decisive. Theodora made her mark in three different areas: the strengthening of the institution of marriage, the banishment of prostitution and the provision of welfare for those who weretraumatized.

For Theodora, marriage was the the "holiest of all institutions", as Diehl (1979) highlights. Her convictions were fully supported thanks to a range of laws that expanded the rights of women. A first big step was taken thanks to the legitimization of marriages between men and women of different social classes. With regards to this, a marriage between a citizen and an ex-slave woman, or one who has been an actress, was to remain intact, even if the husband was made a senator. A similar reform allowed senators to marry the daughters of tavern-keepers or pimps. Dowry, in addition, was described as “strictly unnecessary” and being rejected on the basis of not having one was strictly prohibited. As the law stated: “mutual affection is what creates a marriage”. In other words, the main prerequisite for a marriage has been defined as the consent from both the woman and the man.

Νo woman, thus, could be forced to marry any man, but any woman could marry the man of her choice.

While laws surrounding marriage were loosened, it was also possible to get a divorce, but this was made more difficult. A woman could divorce her husband due to treason, attempts on her life and being falsely accused of adultery, while a a man could divorce his wife if she committed adultery, was away from the house and not with her parents or betrayed him. The killing of adulterous wives was strictly forbidden. Although these reasons may seem ridiculous to us, they were particularly progressive and beneficial to the women of the era. This becomes even more apparent if we consider that if a woman wanted to stay with her husband she would just have to live by specific guidelines. So, because husbands could not just simply decide to divorce their wives, it allowed the women better opportunities to obtain status. As Thomas (2005) argues,

"this law was hugely beneficial for the respect of women and it helped men to view them more as human beings"

Nevertheless, to justify Diehl's (1979) characterization of Theodora as "deeply feminine", we need to examine the laws against prostitution. Her interest in helping the unfortunate is shown in the following words of an imperial edict, which was clearly inspired by her:

"We have set up magistrates to punish robbers and thieves; are we not even more straitly bound to prosecute the robbers of honor and the thieves of chastity?"

Arguably, her early exposure to the realities of a lower class upbringing, and her awareness of all the evils that women of this class could suffer, led her to take a personal interest in such issues. This is closely related to the charitable actions she has undertaken, according to historians. These included reforms on regulating prostitution and also setting up establishments for women on the streets where they could receive help and guidance (Garland, 1999).

Prostitution was always an issue, especially in the empire's capital, Constantinople. Numerous were the pimps who were conducting their business in brothels, selling others' bodies. Young girls were being forced unwillingly into a life of unchastity after being enticed away from their parents by promises of clothes or food and by being led to believe that their contracts with or promises made to their pimps were legitimate. Theodora, aspiring to put an end to their hardship, devised a range of plans to end this phenomenon. As early as 528 AD, she was involved in taking action against pimps and brothel-keepers who were forcing poor girls into prostitution. She ordered that all such people should be outlawed and arrested. She also paid for young girls to be freed from them Nilson (2009). As a resource for their new life, she presented the girls with a set of clothes and offered monetary support to each of them. In this way, the state was cleansed of the pollution of brothels and the women who were struggling with extreme poverty were provided with a way of becoming independent.

Her benevolence, however, was limited to these acts. Mallet (1887), by making an allusion to earlier historical accounts, refers to a stately palace that was build on the shores of Bosporus and that was used as a refuge for the unhappy women and former prostitutes whom Theodora had rescued from the streets of Constantinople. To make it of lasting benefit, she endowed the palace with an ample income of money and added many remarkable buildings, so that these women would never be compelled to depart from the practice of a virtuous life. Moreover, before Theodora was empress, raping a lower class woman or a slave was legal, "but she enacted a law making the rape of any woman punishable by death", as Nilsson (2009) states. Women now protected by the law from sexual offences. At last, women who were charged with major crimes were also benefited, as legislation was passed that stated that they were to be sent to a convent or be guarded by reliable women, aiming to ensure their protection.

A springboard for change

Procopius (1996) writes that Theodora "was naturally inclined to assist women in misfortune". Although we cannot me sure as to what degree her charitable actions arose from a natural charisma, we can be sure that their effect was turning the prevailing tide of silence, and promulgated the high prevalence of violence against women and girls and to fight for their rights. As Garland (1999) argues, 'No doubt she brought greater knowledge to bear on the problems suffered by the lower class than the usual great lady in Byzantium, and it would be satisfactory to think that her measures were more successful than was customary'.

These days, Theodora's remembrance isn't just able to trigger a sense of nostalgia, but rather to serve as a strongly promising motivator for the future of a changing world. Her feminism, consequently, can be deemed a visionary one; one that managed to instigate a shift of perception towards female dignity in many aspects, from respecting the chastity of the female body, to giving women the right to choose their own destiny in life. Her feminism was also one that was also meant to pave the way for later proponents’ realizations of an egalitarian society, because, as resonantly stated in another law of her age:

'In the service of God there is no male or female, nor freeman nor slave’.

References

Austin, Cheridan E., "Sex and Political Legitimacy: an Examination of Byzantine Empresses (399 -1056 c.e.)" (2010). Honors College Theses. 94.

Barker, J. (1966). Justinian and the later roman empire. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

Diehl, C. (1979). Byzantine portraits (H. Bell, Trans.). New York: A.A. Knopf.

Diehl, C. (1905). Théodora, impératrice de Byzance [Theodora, empress of Byzantium],(5e éd. ed.). Paris: H. Piazza.

Garland, L. (1999). Byzantine empresses : Women and power in Byzantium, aD 527-1204. London: Routledge.

García-Moreno C., Zimmerman c., Morris-GehringA. , Heise L. , Amin A., Abrahams N. , Montoya O.,Bhate-Deosthali P, Kilonzo N, Charlotte Watts (2015), Violence against women and girls. Addressing violence against women: a call to action, Papers WHO.

Gregory, T. E. (2005) A History of Byzantium. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

Horner, T., Paulin, J., Stackhouse, H., Stephen, C. (2010, March 19) The status of Byzantine Women.

James, L. (2001). Empresses and power in early byzantium (Women, power, and politics). London: Leicester University Press.

James, L. (2009). Men, Women, Eunuchs: Gender, Sex and Power. In J. Haldon, The Social History of Byzantium. Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Korte, N. E. (2004). Procopius’ Portrayal of Theodora in the Secret History: ‘Her Charity was Universal’. Hirundo, Vol.3 (2004)

Lankila, T. (2008) "The Unkown Empress: Theodora as a Victim of Distorted Images." Language and the Scientific Imagination: 113. Web. 3 Feb. 2010.

LeBel, K., McLaughlin, M. (n.d.) The Byzantine Empress Theodora. 1-5.

Mallet, C. E. (1887). "The Empress Theodora." The English Historical Review: 1-20. Web. 15 Feb. 2010.

Nilsson, C. (2009). "Perspectives of Power: Byzantine Emperor Women." Preteritus 1 : 4-13.

Procopius of Caesarea, The Secret History as cited in: “Procopius The Secret History.” (1996)

Teall, J., & Barker, J. W. (1967). Justinian and the later roman empire. The American Historical Review, 72(3), 941-941. doi:10.2307/1846682

Thomas, J. C. (2005). Justinian’s law as it applied to women and families.

Vasiliev, A. (1958). History of the byzantine empire (2nd English ed. ed.). Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

V., Fagles, R., & Knox, B. (2008). The aeneid (Penguin classics deluxe edition). New York: Penguin Books.