Right-wing Gramscianism: the hegemonic project of Thierry Baudet

After WWII, Antonio Gramsci became one of the left's favorite intellectuals. In recent decades, however, prominent right-wing figures, including Thierry Baudet, have started applying his lessons to their own way of approaching politics.

Baudet and Gramsci

In October 2019 Baudet (leader of the Dutch political party Forum voor Democratie, FVD) spoke at a conference organised by the American Freedom Alliance. He recited his usual speaking points (e.g., criticizing mass migration, the EU, and the general ‘obsession’ with climate change), but at the end of his speech Baudet mentioned how his opponents had spread their worldview, concluding that:

"Antonio Gramsci was a far greater revolutionary than Lenin. I think the great Italian philosopher Antonio Gramsci, when he was writing about power in the 1920s in Italy, he said that [...] we shouldn’t be merely taking over power such as the Leninists had done in Russia because power can be toppled, revolutions can be orchestrated, governments can change, but we need to get [...] into the institutions of society. And then he used an incredible metaphor, which I think is beautiful, he said the electorate and power comes and goes like the tides of the sea. You have high tide and low tide and these are somewhat like the polls we experience with our several political movements. [...] But we need to get to the undertide, [...], the stream under the tides of the sea, the deep stream, where actually power can be institutionalized in a much more stable manner. And that’s why I think it is so important what we’re doing here. Because we’re creating not just a political narrative and political alliances, but cultural and societal alliances."

It is noteworthy that Baudet, a self-proclaimed nationalist and conservative, refers to Gramsci, a communist, with admiration.

It is noteworthy that Baudet, a self-proclaimed nationalist and conservative, refers to Gramsci, a communist, with admiration. He is, however, not the first right-winger to show an affinity with Gramsci. In Belgium (Sam Van Rooy, Filip Dewinter, Tom Van Grieken and Joachim Pohlmann), Italy (Matteo Salvini), and France (Marion Maréchal-Le Pen), right-wing politicians have done likewise. References to Gramsci (and thus also his texts) are essential in understanding their goals and way of doing politics. By focusing on Baudet I hope to provide insight into this unusual marriage.

By examining right-wing intellectuals’ interpretations of Gramsci, I will describe the development of a right-wing gramscianism. The intellectuals considered here are Roger Scruton, Paul Cliteur, Sid Lukkassen (with regard to cultural marxism), and the Nouvelle Droite. Using this framework, I will proceed to analyze Baudet's discourse. I do not intend to elaborate his political points but rather will concentrate on his strategic statements. This will allow for a better grasp of Baudet’s reference to Gramsci and his place in a broader movement.

Roger Scruton, cultural marxism, and the Nouvelle Droite

Roger Scruton was Baudet’s PhD supervisor and originated the term ‘oikophobia’, which would become the title of a book by Baudet. In his written work he focuses mainly on Gramsci’s concept of hegemony. According to Scruton (2007, p. 280-281), hegemony for Gramsci consists of “complex and concealed modes of class domination, whereby positions of influence throughout society are always, by a hidden mechanism, filled by the members of an already ruling class.”

The task of the revolutionary is therefore to infiltrate the institutions through which hegemony is exercised - e.g., universities, councils, the church - and weaken their staying power. The revolution itself then involves the construction of a brand-new hegemony that would, in Gramsci’s case, spread itself from the communist party all throughout civil society. Furthermore, Scruton (2015) considers Gramsci to be the basis of the so-called ‘culture wars’ raging on American college campuses. It is the Italian who started this cultural revolution and removed the notion of class from its economical and material foundations.

This view is also at the center of the discourse surrounding ‘cultural marxism’ in the Netherlands, as spread by key right-wing figures like Sid Lukkassen and Paul Cliteur. According to them, Gramsci came up with a new political strategy - the war of position or the long march through the institutions - and in doing so shifted attention from the economic base to the cultural superstructure. Hegemonic ideas, which constitute the superstructure and are consented to by the general public, had to disappear. The most efficient way of doing so would be taking over universities and media in order to indoctrinate the people. Those who oppose 'cultural marxism' claim that the Frankfurt School followed through with Gramsci’s mission and, as of May ‘68, completed his march. From then on the left has, allegedly, represented the voices of women, minorities and homosexuals and limited public debate to climate, diversity and racism.

Cultural Marxism

This evolution, which would inevitably lead to the decline of Western civilization, is what Lukkassen and Cliteur want to halt. Although they do not subscribe to the ideas that Gramsci and his followers allegedly wanted to implement, they do affirm the effectiveness of his strategy. Hence a plea for a right-wing gramscianism has emerged, with their own agenda for a long march through the institutions, to counter cultural marxism. Lukkassen (2018, p. 66) thus endorses the creation of the right's own 'New Pillar', with accompanying institutions and culture-bearing bodies. However this isn't an original invention of Lukkassen's - right-wing movements in the late 60s, traditionally referred to as The New Right, had exactly this in mind when opposing the ‘68 movement.

The most infamous movement from this period is the French Nouvelle Droite. Their foreman, Alain de Benoist, wanted to push the radical-right in a new and more intellectual direction: away from the sometimes-violent battle over political institutions and towards a long-term struggle for hegemony (Maly, 2018). Reading Gramsci’s texts, de Benoist found instruments and ideas to fulfill this task. He learned that whoever possessed cultural power could influence civil society's reigning norms and values.

De Benoist's plans for revolution had to begin with the “transformation of general ideas” as embedded in, for example, traditions. The starting point of that transformation would be “ideological reflection, philosophical construction, political education, and dialogue with the adversary” (cited in Casadio, 2014, p. 53). De Benoist therefore decided to give up on party politics and fully dedicated himself to metapolitical struggle at the cultural level, resulting in various think tanks, institutes, seminars, conferences, journals, and books (Maly, 2018). According to Bar-On (2014), the recent success of extreme- or radical-right parties, as well as ever-growing criticisms of multiculturalism and anti-migrant rhetoric, are all indebted to the Nouvelle Droite and the efficacy of their strategy.

Thierry Baudet's project

Forum voor Democratie was founded as a conservative and eurosceptic think tank but later developed into a political party. Baudet’s decision to enter politics seems curious given that he thinks intellectuals are changing society, not politicians, and he often speaks of parliamentary work with disdain. As reflected in the quote at the beginning of this article, he believes that power is institutionalised in different ways. The composition of political institutions reflects the people's preferences, but these ebb and flow: the left will win one election, the next one will be won by the right.

In Baudet's eyes, the most successful Dutch political party of the last thirty years has been GroenLinks, the green left. Although GroenLinks has never been part of the government, their agenda has nonetheless been carried out. From this Baudet infers that GroenLinks has accomplished the long march through the institutions and now dominates all layers of society, except the political one. He sees their agenda in action in universities and schools, the judiciary, institutes responsible for asylum and migration, editorial boards of newspapers, tv-shows, and all sorts of urban development, spatial planning and organisational authorities. In other words: underneath the volatile political tastes of the people, one can find an undercurrent of green-left ideology.

Baudet and GroenLinks

Baudet, however, represents a completely different conception of the world. To cultivate his views throughout society, he wants to use the same approach that has brought his opponents so much success. He has called on the FVD's youth wing to build its own ecosystem and train its members to take up important societal posts. In order to fundamentally transform society and policy, Baudet urges his audience to storm institutions through cultural means. The word ‘fundamental’ is of utmost importance here. Baudet has stated repeatedly that he doesn’t simply want to govern or make policies. He doesn't want to be just another player on the board: he wants to alter the board all together. His goal is to change public opinion, form a collective will, and steer society in a completely different direction.

His strategy also includes several extra-parliamentary initiatives. First is FVD’s ‘Renaissance Instituut’ - according to its website, this research and training institute is basecamp for the march through the institutions. For example, in the past it has targeted Dutch teachers allegedly forcing their political views on students or 'indoctrinating' them. Education, science, and the media have all become sites of ideological struggle. Baudet considers the 'fake news-spewing' mainstream media one of his fiercest enemies. He has thus sought out alternatives for communicating his version of the facts, namely television broadcaster ‘Ongehoord Nederland’ and the FVD’s own news program on YouTube.

Right-wing gramscianism

Following in the footsteps of the Nouvelle Droite, Baudet started his metapolitical mission by establishing a think tank. Based in his conviction that ideas rule the world, he thus regarded the role of the intellectual - who shapes and structures ideas into a coherent worldview for the public - as critical to society. Although Baudet still describes the FVD as a broad cultural movement, he also now realizes that the political cannot remain untouched. He has therefore waged his hegemonic battle on two fronts: one, breaking open the political order from the inside and two, targeting institutions to reverse the May ‘68 revolution and change the 'undercurrent.' This is why Baudet is such a fan of Gramsci's: cultural hegemony, not just political power, is key in bringing about change. Gramsci, says Baudet, “understood the need of culture as an undercurrent. The globalist movement has been very successful in monopolizing this undercurrent.” Consequently the core of his politics is the “cultural battle” to “replace the current hegemony.”

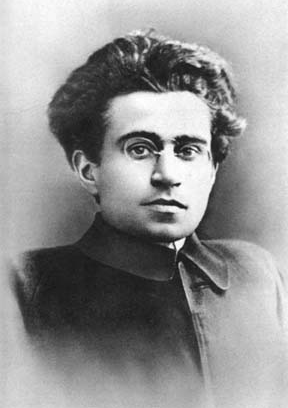

Antonio Gramsci

The concept of hegemony - in Baudet’s vocabulary synonymous with power over the undercurrent - is probably Gramsci’s most known (and most important) idea. One of the starting points of Gramsci’s analysis was the absence of revolution in the West (Thomas, 2009). This made him realise that the Italian labour movement had to pursue an alternative strategy. Contrary to more orthodox marxists who thought that eventually capitalism’s inherent contradictions would cause the system to collapse almost spontaneously, Gramsci believed deliberate action was necessary (Bocock, 1986; Simon, 2015). Society had developed in such a way that classical-marxist, economically-determined schemes did not apply anymore. Parliamentary democracy had become the prevailing form of government and capitalism continued to expand. Relations within the state and between states grew more complicated.

Apart from political society's public institutions, institutions within civil society - for Gramsci, the complex of private and voluntary institutions including trade unions, churches, political parties, charitable and other societal organisations (Simon, 2015) - started playing a political role as well. The ruling class could exert its power on two levels, but also in two different ways. According to Gramsci (1971, p. 12), civil and political society corresponded respectively to “the function of “hegemony” which the dominant group exercises throughout society and on the other hand that of “direct domination” or command exercised through the State and “juridical” government.” Hegemony here refers to:

"The “spontaneous” consent given by the great masses of the population to the general direction imposed on social life by the dominant fundamental group; this consent is “historically” caused by the prestige (and consequent confidence) which the dominant group enjoys because of its position and function in the world of production." (p. 12)

Governing, in the strictest sense, however, comprised: “[t]he apparatus of state coercive power which “legally” enforces discipline on those groups who do not “consent” either actively or passively” (p. 12). A hegemonic class was able to rule with the consent of the people, therefore grounding its power that much more firmly. As a last resort it could fall back on coercive means, but due to the functioning of parliamentary democracy, controlling an entire people by pure coercion was impossible. If the communists wanted their revolution to succeed, it was crucial to first win hegemony in the ‘trenches’ of civil society.

At this point it is important to underline that Gramsci’s ultimate goal was always to overthrow the capitalist system. The right-wing gramscianism, as described above, omits this element. The gramscian arsenal is stripped of its original marxist connotation and can thus be used by anyone, across the political spectrum. Today it serves as a ‘simple’ politico-strategical mechanism: power functions on different levels and to successfully establish a hegemonic project one should gain ground in all of them. Therefore, when Baudet claims to be a revolutionary, he does not refer to a violent overthrow, but rather a cultural revolt against dominant ideas - a revolution in the minds of the people, not in the streets.

Baudet once said that his movement meant the "return of the political." It seems he's bringing Gramsci with him.

Right-wing intellectuals' have taken Gramsci's emphasis on the superstructure and civil society as explanation for their belief their idea that, over the last 50 years, the left has indoctrinated the masses and eliminated dissent from the public debate. By imitating his opponents’ tactics, Baudets wants to awaken the west from its 'indoctrinated' state. This false consciousness, crystallized in a particular worldview and common sense, currently keeps the population in line. Baudet perceives this worldview as illusory and unnatural, implying that it is being forced on everyone. Once one escapes its influence, one will finally see the truth, specifically his truth. The hegemony of the present order is a construction and, in order to maintain itself, has to be discursively articulated time and time again by the different sectors and institutions that make up the hegemonic apparatus of the ruling elite. Only in this way can it secure the people’s consensus and avoid possible crises.

This train of thought also works in the opposite direction. If one is able to undermine said apparatus, it will lose influence and the hegemony will start to waver. It is this gramscian element that has interested right-wing movements for several decades and is currently being harnessed by Baudet. By walking down this same path, he hopes to seize control over all strata of society - which he, following Gramsci, deems the only possible way to realise a revolution. The Nouvelle Droite’s gramscian metapolitics is combined with the anti-cultural marxists’ long march through the institutions and supplemented by political action. Here Baudet shows himself to be a better Gramsci adept than, for example, de Benoist, who relinquished party politics all together. Despite his clear contempt for the political game, Baudet makes good use of his speaking time in the parliament to spread his message and combat his adversaries. By way of motions and interpellations the FVD can pressure policy makers; something the Nouvelle Droite has never been able to do, even though their ideas have been taken up by different parties throughout the years. Baudet once said that his movement meant the "return of the political." It seems he's bringing Gramsci with him.

References

Bar-On, T. (2014). The French New Right: Neither Right, nor Left? Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 8(1), 1-44.

Bocock, R. (1986). Hegemony. Ellis Horwood.

Casadio, M. (2014). The New Right and Metapolitics in France and Italy. Journal for the Study of Radicalism, 8(1), 45-86.

Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the Prison Notebooks (Q. Hoare & G. Nowell Smith, Trans. & Eds.). International Publishers.

Lukkassen, S. (2018). Gramsci en zijn invloed op het hedendaags marxisme. In P. Cliteur, J. Jansen & P. Pierik (Eds.), Cultuurmarxisme. Er waart een spook door het Westen (pp. 41-73). Uitgeverij Aspekt.

Maly, I. (2018). Nieuw rechts. EPO.

Simon, R. (2015). Gramsci's Political Thought: An Introduction. Lawrence & Wishart.

Scruton, R. (2007). The Palgrave Macmillan Dictionary of Political Thought: Third Edition. Palgrave Macmillan.

Scruton, R. (2015). Fools, Frauds and Firebrands. Bloomsbury Publishing.

Thomas, P. D. (2009). The Gramscian Moment. Philosophy, Hegemony and Marxism. Koninklijke Brill NV.