“Bring back manly men”: discourses on the Harry Styles Vogue cover

On November 13th, 2020, U.S. Vogue announced their new cover star. However, this specific cover received far more attention than usual. Singer-songwriter Harry Styles appeared on the December cover, with some arguing that Vogue had made history by featuring its first-ever male cover star. However, a discussion erupted around what Styles was wearing on the cover: a blue Gucci gown and tuxedo jacket.

Harry Styles and gendered fashion

Vogue’s cover announcement on Twitter (Figure 1) included a quote from Styles and a link to the corresponding cover story. The tweet highlights a particular excerpt in which Styles expresses his joy in playing with clothes and implies that clothes can be a source of joy and creativity. Two pictures from the photoshoot were included as material representations of how Styles likes to play with clothes. There is no explicit indication here of certain types of clothing being assigned to gender. However, the dress he is wearing (on the right) ignited a discussion on Twitter, where different views on gender roles met.

This discussion, one might argue, was sparked by discourses regarding what is considered normatively ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ fashion. Skirts and heels are thought of as feminine in contemporary society (Barry, 2018). Especially in Western societies, skirts and dresses are rarely worn by men. There seems to be a social barrier to wearing skirts or dresess, as it might lead to negative prejudices or responses. When a man does choose to wear a skirt-like garment, there is often a specific (cultural) reason or meaning behind it – take for instance the kilt, which expresses Scottish national pride (Porter, 2002).

A study by Barry (2018) found that men will occasionally wear so-called ‘feminine’ clothing, but only if it doesn’t contradict gender expectations or hegemonic ‘masculine ideals’ in a given context. Even designing men’s skirts for commercial purposes is so remarkable that, as fashion writer Charlie Porter (2002) put it, it could be seen as an attempt “to shift the male into a new social context.”

Even designing men’s skirts for commercial purposes is so remarkable that it could be seen as an attempt “to shift the male into a new social context.”

Figure 1. “There’s so much joy to be had in playing with clothes.”

Candace Owens' response

A significant contribution to the discussion surrounding Styles’ Vogue cover was Candace Owens’ reply to Vogue’s tweet (Figure 2). Candace Owens is an American conservative political activist. She became known after one of her YouTube videos gained the attention of news media. In this video, Owens calls claims the media is attempting to create racial hysteria. Her political voice only grew more when she was later acknowledged by former President Donald Trump.

In her reply to Vogue, Owens mentions the importance of “strong men” for the survival of a society. She refers to processes of male "feminization", and "Marxism being taught" to “our children”, which she considers to be an intentional “attack” on Western society.

Figure 2. “There is no society that can survive without strong men.”

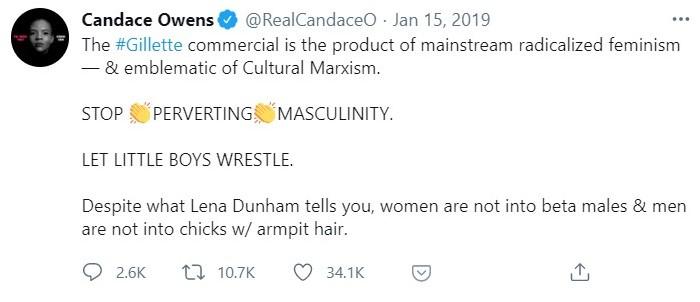

This is not the first time Owens has mentioned Marxism in her tweets. In 2019, she tweeted about an ad campaign by the shaving brand Gillette (Figure 3). The campaign video was launched in response to the #MeToo movement and shows instances of sexism, both in mainstream media and everyday life. Owens criticizes the campaign’s narrative of masculinity. She considers it to be a product of "mainstream radicalized feminism" and typical of Cultural Marxism. What these two of Owens' tweets have in common is that they criticize one of the main tenets of feminism: challenging traditional gender roles.

Figure 3. "The Gillette commercial is the product of mainstream radicalized feminism - & emblematic of Cultural Marxism"

Cultural Marxism

The conservative narrative of (cultural) Marxism as an attack on Western society dates back to at least 1997, when Paul Weyrich, cofounder of the Heritage Foundation, refered to “Cultural Marxism” and the Frankfurt School as “enem[ies] of our traditional culture”. The phrase “Cultural Marxism” is relatively new, but the word "cosmopolitan" was used throughout the 20th century to similar effect. According to German historian Volker Ullrich, "cosmopolitan" was used as an anti-Semitic term by both Nazis and Bolsheviks. In Nazi Germany, it was used to describe Jewish characteristics that were considered to be racial “pollution”.

Jeff Greenfield (2017) notes that this phrase is generally used when labeling individuals or movements that deviate from a nation's traditional beliefs. In short, within Cultural Marxism discourse there generally has been an opposition to any form of diversity, including gender. Although this discourse has been around for decades, digital media has enabled its rapid spread online (Busbridge et al., 2020).

Within Cultural Marxism discourse, there generally has been an opposition to any form of diversity.

Owens’ reply shows how the term “Marxism” is being used in political (neoconservative) discourse. She refers to the idea within the Cultural Marxism conspiracy that Western traditional cultural values are threatened by the promotion of liberal cultural values. Here, Cultural Marxism is seen as the cultural side of “globalism” that harms societal structures. This general idea also considers the concept of “patriotism”, in which one has the monopoly in one’s own country, to be the ideal circumstance. Note that “globalism” must not be confused with the term “globalization”. Globalization is a concrete, objective development, related to the interconnectedness of the world with “hard” (economic and political) and “soft” (cultural and ideological) dimensions (Blommaert, 2019).

"The East" vs "The West"

Owens also explicitly mentions “the East” and “the West” in her tweet. These are broad concepts that do not tell the reader much about which specific regions she is referring to. Still, it seems that through these concepts, she attempts to give examples of places where gender roles conform to (her idea of) traditional gender roles (Maly, personal communication, March 1, 2021). She implies that the East is a more enduring society than the West due to the West lacking “strong men”. By describing a "steady feminization of men", she seems to believe that Western society lags behind when it comes to masculinity.

This relates to the previously mentioned opposition to diversity in Cultural Marxism. However, it is also similar to Balibar’s (1991) concept of “neo-racism” in times of superdiversity, which emphasizes culture rather than race. Neo-racism has brought a discourse of racism in which the ideal situation is one of cultural homogeneity. Within this framework, all changes to tradition - through multiculturalism or the reformulation of gender roles - signal a degeneration of culture. The underlying assumption in Owens' tweet is that Eastern society has a culture that doesn't allow for the feminization of men. Western society, in her view, has been watered down as a result of Cultural Marxism. Her discourse on cultural degeneracy and Cultural Marxism is grounded in an essentialist notion of culture.

Neo-racism has brought a discourse of racism in which the ideal situation is one of cultural homogeneity.

Styles’ choice of clothing does not meet Owens' definition of traditional cultural values. At the end of her tweet she calls on her Twitter followers to “bring back manly men”, further indicating that Styles does not fit her definition of masculinity. Owens identifies Styles as an antagonist, or, elaborating on Howard Becker's (1963) notion, an "outsider."

Constructing Styles as “outsider”

According to Becker (1963), an outsider is anyone who is judged to have broken social rules. Such social rules are enforced by social groups or societies and may apply to everyone in this group; they are created and maintained through labeling certain behavior as “deviant”. Because different social groups enforce different rules, what one considers to be “deviant behavior” varies. In short, deviance is a product of society and a result of responses to another person’s behavior. In this specific case, whether Styles’ clothing can be seen as deviant depends on how others react to it (Becker, 1963).

The data in this article show a conflict between different social groups with different rules: there is disagreement on whether Styles’ "playfulness" with fashion is positive or acceptable. Owens takes a traditionalist position and judges Styles’ clothing as violating social rules (Becker, 1963). Owens seems to attach great importance to Styles following the “rules”. She sees Styles' Vogue cover as an example of male feminization, i.e. an “outright attack” on Western society. In other words: Owens seems to believe that Styles shows deviant behavior and that does not benefit society.

To Owens, the societal need for strong men cannot be questioned: it is presented as 'normal' or even natural. She refers to “the East” as a part of the world that maintains certain fundamental ideals in line with her own concept of a "strong" or "good" society. This is in opposition to a deteriorating Western society, thanks to liberal cultural values (Maly, personal communication, December 7, 2020).

As a political figure with many Twitter followers, Owens appears to be in a powerful position to determine and enforce certain social rules. However, her reach does not necessarily imply the successful enforcement of such rules. On Twitter, the addressees are unknown to the interlocutor, meaning there is always an issue of uptake (Blomaert, 2019). Different contextual universes often meet, resulting in clashes between individuals and social groups (Blommaert, 2005).

Disagreements with Owens

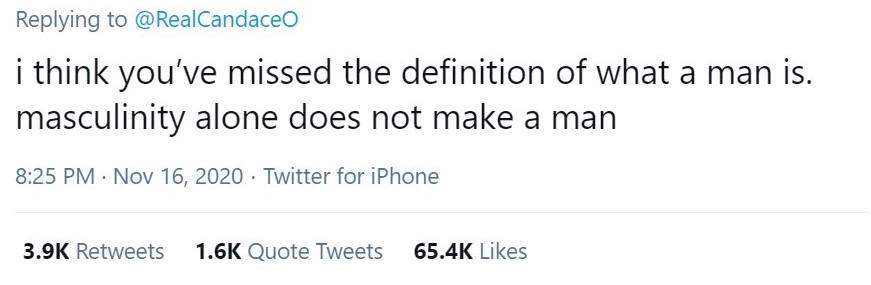

Exactly what Owens meant by “manly men” was questioned by many Twitter users. One user responded that she had “missed the definition” of what it means to be a man (Figure 4). This seems to be a counter-attempt to define normality: it implies that Owens' definition of what a man should be is incorrect. Although this person notes that "masculinity" is not the defining aspect of a man, no concrete definition is given in this response. This person judges Owens as the outsider: there appears to be a definition of “being a man” she is unaware of, and her views are thus labeled as deviant.

Figure 4. “i think you’ve missed the definition of what a man is.”.

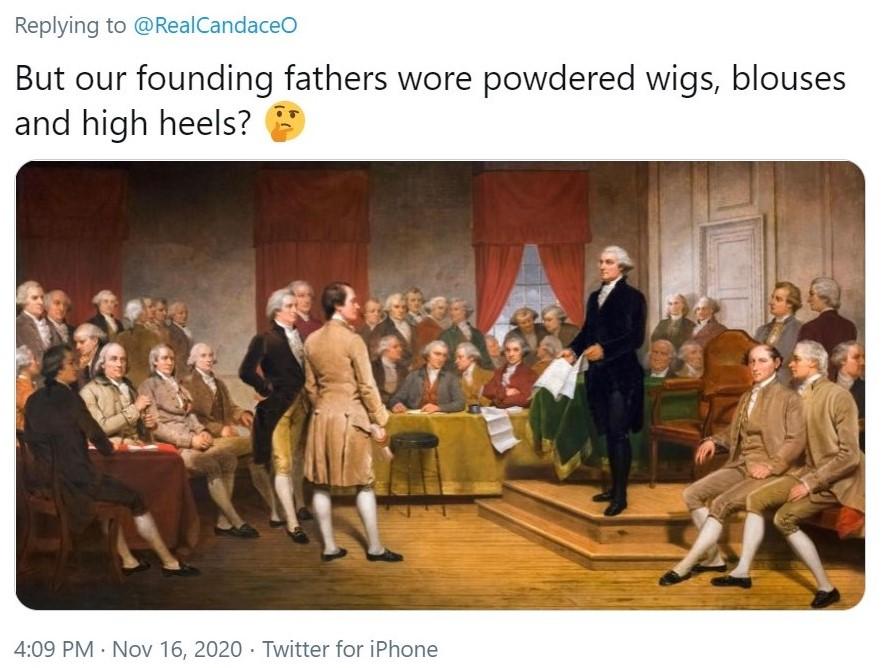

Other Twitter users highlighted several historical male figures. Many provided images to show that men have worn dresses or skirts throughout history (Figure 5 and Figure 6). Figure 5 shows a tweet referencing the painting “Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention”, painted in 1856. This work represents George Washington, first President of the United States, at the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia. The tweet calls Owens’ views on society and her claim to normalcy into question. The attached image refers to men’s fashion the 18th century, certain elements of which, for instance skirted garments, do not or rarely occur in 21st century men's fashion. It demonstrates that gender-specific clothing items are socially constructed in a specific time-space. When looking into history, what constitutes "acceptable" men’s fashion strongly depends on place and time.

What constitutes "acceptable" men’s fashion strongly depends on place and time

Figure 5. “But our founding fathers wore powdered wigs, blouses and high heels?”

Figure 6 shows a similar response. It provides multiple images of historical men's clothing items that were judged to be appropriate at the time. The image on the left is of a character from the TV show “Spartacus”, which is set during the Roman Republic. The bottom-right image shows similar clothing styles from that period, and the top-right image is of medieval entertainers wearing dress-like garments.

Figure 6. “men in history have worn this 👏"

What we would now call skirts were worn by both men and women in various ancient civilizations. These responses further illustrate that concepts “feminine clothing” and “masculine clothing” are not fixed. The division between skirts for women and pants for men was not normalized until the 19th century. This makes it clear that Owens refers a specific time – likely the mid-20th century – to normalize her position. What this means, in short, is that the time period one references in this dispute plays a significant role in what could be labeled as acceptable or deviant.

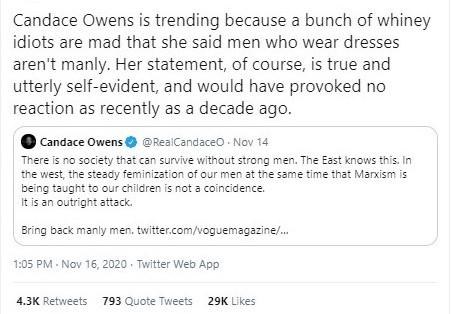

Owens' supporters

Several Twitter users, on the other hand, supported Owens’ views. Figure 7 shows a tweet linking Owens’ tweet's virality to the criticism it received. In an effort to minimize their credibility and invoke judgement, those criticizing Owens are categorized as “whiney idiots”. The addition of “of course” and “self-evident” when describing Owens’ statement implies that there is no questioning her views and that the poster agrees with the social rules Owens is trying to enforce. This person thus, ironically, highlights the modes by which Owens tries to normalize her position. They refer to yet another point in history, resonating with the time period Owens referred to in her own tweet.

Figure 7. “Candace Owens is trending because…”

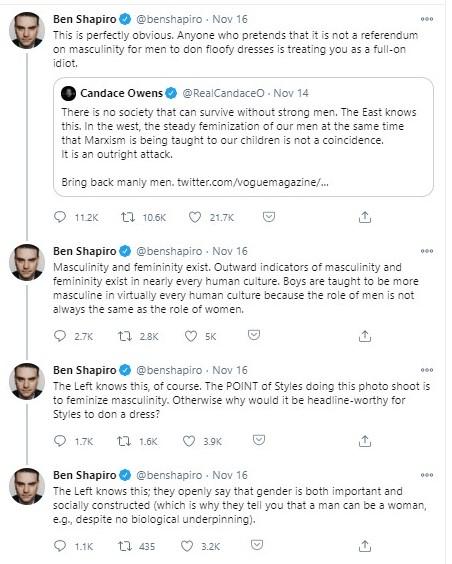

Owens’ views were further supported by Ben Shapiro (Figure 8), an American conservative political commentator and lawyer. He elaborates on Owens’ tweet, stating that men wearing dresses is "a referendum on masculinity". He argues that those who do not agree with this treat Owens like a “full-blown idiot”. This explains, from Shapiro’s point of view, why she has received such strong, negative responses. As for the Vogue U.S. cover, he believes that it is only "headline-worthy" because Styles is, as he calls it, "feminizing masculinity".

Shapiro argues that the concepts of ‘masculinity’ and ‘femininity’ each have "outward indicators". He does not go into further detail about what such indicators consist of, but his disapproval of Styles’ clothing implies that wearing a dress does not conform to his idea of masculinity. Regardless of this ambiguity, Shapiro mentions in his last tweet that Left-wingers see gender as socially constructed, implying that he does not see it as such. This raises a question of power: if these concepts are not socially constructed through discourse, like Shapiro believes, then who gets to define them?

This raises a question of power: if these concepts are not socially constructed through discourse, like Shapiro believes, then who gets to define them?

Figure 8. “This is perfectly obvious.”

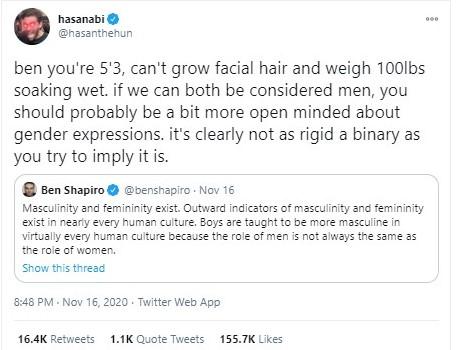

Shapiro was called out on his second tweet by Hasan Piker, a political commentator and Twitch streamer (Figure 9). Piker's response shows that, unlike Shapiro, he approaches the definition of a man as something relative. Piker physically compares himself to Shapiro, imply that, based on their physical characteristics and according to heteronormative discourses, Shapiro might labeled as an “outsider” by society for failing to conform to masculinity.

Figure 9. “ben you’re 5’3, can’t grow facial hair and weigh 100lbs soaking wet.”

Gender roles, normativity and discursive practices

Each of these comments has made judgements on one specific object: Harry Styles wearing a dress on the cover of Vogue. Often they refer to different time periods in which different aspects of male fashion were judged to be “normal”. The tweets shape these events through their own analysis, many of them using Charles Goodwin’s (1994) discursive practices: coding, highlighting and communicating material representations (visuals). These practices help to create socially organized ways of seeing and understanding events, accountable to the interests of a specific social group (Goodwin, 1994).

Coding can mold reality into categories and shape one's perspective (Goodwin, 1994). In her reply to Vogue, Owens uses “the East” and “the West” to describe what she believes are the two main civilizations in the world. In doing so, she uses the East to criticize the West. Her use of “our men” and “our children” implies that her message is directed at those living in Western society. To her, Styles does not look like a “strong man” - his way of dressing implies a “feminization” of men, which she believes is weakening Western society. Her use of the word “attack” communicates her belief that this feminization and the influence of Cultural Marxism are violent and harmful.

While virtually every piece of data considered here mentions “masculinity” and “femininity” in some way, the definitions these concepts vary widely. The meaning individuals mobilize indexes their political position. While some feel threatened by the expression of femininity in a way they are not familiar with or ideologically oppose, others applaud it. By refering to different historical periods, people highlight information that supports their own perspective. What is made salient in this process shapes one’s perception.

While virtually every piece of data mentions “masculinity” and “femininity” in some way, the definitions these concepts vary widely.

In the case of the Harry Styles Vogue cover, Owens judges Styles to be an outsider per the heteronormative standard that women wear dresses, a convention that arose in the 19th century. Some, in disagreeing with her, do so by referring to men wearing skirt- or dress-like clothing centuries ago.

This debate shows the importance of context. Because discourse is language in use, its meaning heavily relies on context. According to Cameron (2001), the message of a text relies on its context, and its interpretation depends on “real-world knowledge” that the text does not cover. What is judged as “normal” about a specific event depends on the community doing the judging. The data in this article show different instances of a construction of reality around one specific topic.

Conclusion

This analysis has demonstrated how the definitions of “masculinity” and “femininity” have been, and still are, constructed through discourse. The interpretation of messages regarding this topic heavily relies on one's context and social rules. One’s behavior cannot be “deviant” if it is not labeled as such by others. Indeed, Owens has a certain amount of power, as someone in politics and media, to define and classify people and phenomena. But in an online-offline nexus, everyone has a say. In digital environments, different normalization attempts are made and offered for uptake, revealing information about who states them.

Men's fashion has changed drastically over time, thus illustrating how the "feminization of men" Owens mentions is a social construct with no fixed meaning or characteristics. Rather, the use of these words indicate Owens’ stance towards any men’s fashion that diverges from her own norms. This shows that perhaps, to paraphrase Blommaert & Verschueren (1998), a large part of the problem lies in perceiving diversity as problematic, rather than diversity itself.

References

American Psychological Association. (n.d.). Radical Feminism.

Balibar, E. (1991). Is there a neo-racism?

Barry, B. (2018). (Re)Fashioning Masculinity: Social Identity and Context in Men’s Hybrid Masculinities through Dress.

Becker, H.S. (1963). Outsiders: studies in the sociology of deviance.

Blommaert, J. (2019). Babylon is burning: Jan Blommaert on globalism, globalization and cultural Marxism.

Blommaert, J. (2019). From groups to actions and back in online-offline sociolinguistics. In J. Blommaert, Online with Garfinkel: Essays on social action in the online-offline nexus (pp. 7-12).

Blommaert, J. (2005). Text and context. In J. Blommaert, Discourse: a critical introduction.

Blommaert, J. (2019). Why has Cultural Marxism become the enemy?

Blommaert, J. & Verschueren, J. (1998). Debating diversity: analyzing the discourse of tolerance.

Bowles, H. (2020, November 13). Playtime with Harry Styles. Vogue Magazine.

Busbridge, R., Moffitt, B. & Thorburn, J. (2020). Cultural Marxism: far-right conspiracy theory in Australia’s culture wars.

Emojipedia. (n.d.). Clapping hands.

Fandom TV. (n.d.). Vettius in Spartacus Wiki.

Greenfield, J. (2017, August 3). The Ugly History of Stephen Miller's 'Cosmopolitan' Epithet.

Lynn, A. (2018). Cultural Marxism

Porter, C. (2002, January 26). The great divide.

Rossman, S. (2018, October 19). Candace Owens’ rapid rise defending two of America’s most complicated men: Trump and Kanye.

Shankar, A. (2017). 'Cosmopolitan' is a dog whistle word once used in Nazi Germany and Communist Russia.

Thorpe, J.R. (2017, May 22). The history of men & skirts.

Topping, A., Lyons, K. & Weaver, M. (2019, January 15). Gillette #MeToo razors ad on 'toxic masculinity' gets praise - and abuse.

Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. (n.d.). Washington as Statesman at the Constitutional Convention (primary title).

Wheeler, A. (2020, November 16). Harry Styles wore a dress on the cover of Vogue – and US rightwingers lost it.