How can we explain our online identities?

Today, we share our lives on social media more than ever before. The thinking of French philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault, who both offer very different frameworks for understanding our online identities, could possibly explain the behaviour of users of these social platforms.

Different online identities

The way we live our lives, what we consider moral, inappropriate or justifiable is a personal matter. Being a white queer female will most likely mean that you have a different outlook on life than your religious Arabic male neighbour. What we stand for and support says a lot about our identity as a person. Who we are shapes our lives and therefore, the decisions we make.

In this article, we will tackle the issue of the construction of online identities. With many explicitly different identities to be found on the web, it is possible to put most profiles into boxes. However, not one profile is exactly the same as the other. This means that people with these identities all have different factors that determine their identity construction. They all have different sexualities ruling over their lives, and therefore, their profiles look different (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 On social media we can find different identities. What has shaped each of them?

Online identities like the ones shown above will serve as data to answer our questions. We will examine whether their online actions can be explained through Sartre's and Foucault's theories about behaviour and performed sexualities. Many people let their feelings and opinions take over, and they share them on online platforms. Motives behind this can differ. While some act as spokespeople for like-minded individuals, others might do it impulsively, and do not realize that they are constructing an online identity, which often influences others. Can we explain the constructed identities and images of the body from our sample profiles? We will argue that the thinking of Jean-Paul Sartre and Michel Foucault might yield some answers.

Freedom as burden

According to Sartre, people shape themselves with the choices they make, and having a free choice is made possible with our awareness. This means that there is an immense case of freedom to deal with in our lives. We have the responsibility to create our lives by ourselves. Sartre claims that people regard this freedom in a way that turns it into a sort of a prison, which might have negative connotations (Schutijser, 2009).

Once freedom has broken loose in a human spirit, the gods will no longer have a grip (Sartre, 1983).

So are the consequences of freedom negative? This is unclear, as the only thing you can say is that certain ways of thinking and certain ways of life, such as religion, no longer matter. This is because religion forms us before we can form ourselves (Donkers, personal communication 2015). But doesn't the world become chaotic without these preconceived lifestyles, morals and ideas? What is our foothold then? How do we deal with each other? What is good and what is bad? We are not uniform and everyone's opinions differ. This implies that there is no human nature, since there is no God who could have conceived it. Man is in the first instance as he projects himself, not what he wants to be. Therefore, we begin as a blank slate - tabula rasa (Donkers, personal communication 2015).

This brings us to Sartre’s existentialism, the idea that man does not have a predetermined essence. After WWII people began to believe that man was 'thrown' into the world, in which he was a victim of various circumstances. Even though we are victims, we still carry a personal responsibility, because we choose our own destiny; it is not destined by faith. According to Sartre, man must decide for himself what kind of person he wants to be. The central idea is that man shapes himself through his choices (Sartre, 2007).

Only when you have made a choice, can you find out what it is that you want, or what you want to become (Donkers, personal communication 2015). Our existence is thus characterized by an inescapable freedom which comes with responsibility, whether we want it or not. But this responsibility is also applicable to people around us. Every choice they make can also have consequences for others. According to Sartre, everyone will therefore always choose what seems to be right at that moment. By our choices, we show what a person in our situation should do. With that, we determine what is right for everyone else to do.

Sartre does not, however, deny that there are certain things that limit a man. You have not been able to choose where and in what circumstances you were born, for example, i.e. your language and culture have been given to you. Sometimes, things happen in life that you cannot do anything about. Think, for example, of accidents that render people blind or disabled. He calls these limitations factualities. Sartre says that people are completely free in the way in which they choose to deal with these factualities.

He also points out that many people try to escape their freedom by desperately clinging to a certain conception of who they are, an essence. This is called mauvaise foi (bad faith). According to Sartre, everyone has the choice to do this - he only sees it as a mistake. Mauvaise foi is actually living a lie. You cannot escape true judgment. There are no values for humans besides the ones you create yourself. If you choose these values, and at the same time claim that they are working against you, you are in contradiction with yourself (Howells, 1988).

Holding onto a conception of who we are, mauvaise foi, is living a lie.

Another important concept for Sartre is abandonment, which entails that people are not only stuck with the enormous burden of freedom, but they cannot rely on predetermined morals, rules or laws while making choices, e.g. you cannot rely on Christianity when making your choices. This faith implies to be merciful, love your neighbour, devote your life to someone else, choose the most difficult path etc. But what is the most difficult road? Who should we love? Who can make a judgment about this beforehand? No one. No established morality can determine that for you.

The only thing left is our instinct. Feeling is then the only thing that matters. But how do you determine the value of a feeling? You can only say how much something means to you if you actually made a certain decision or performed a certain action. So the feelings are in the actions you perform, you can be led by them and that will often be the only good option (Donkers, personal communication 2016). You cannot look inside yourself for an authentic state that brings you to act, nor with a morality that offers you guidelines that make your actions possible. You always have to make the choice yourself.

Panoptic society

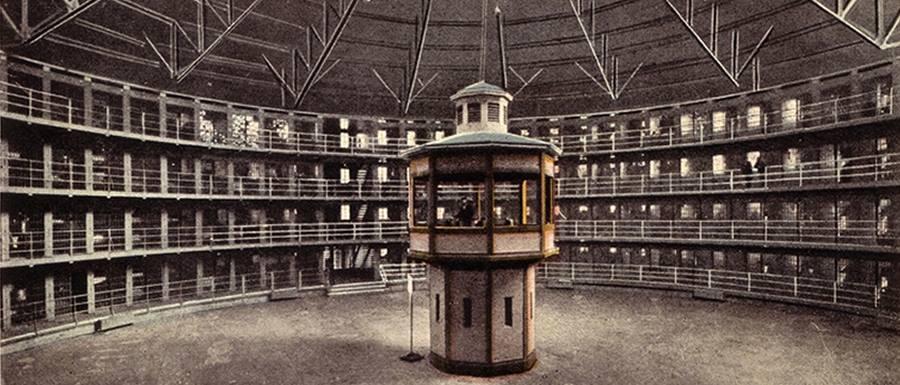

According to Foucault, we are not as free as we think we are. Our whole society is pervaded by power structures. There are norms that tell us how we should behave. Foucault sees society as a panopticon, which is the reason why people also live by these norms. Our society can be seen as a prison in which one is constantly being observed, making him/her behave according to the norms (Fig. 2). This results in disciplining and normalization. We often unconsciously, submit to the rules of power structures present in society, in order to avoid punishment and disapproval.

Moreover, we tend to see the presence of rules and norms as normal. Although Foucault says we are not aware of how power acts upon us, he does not necessarily see it as a bad thing. On the contrary, power is productive. It brings truth and order. Foucault called this pouvoir-savoir. Power is knowledge (Foucault, 2003). The more knowledge one has, the more powerful one becomes.

Fig. 2 The panopticon as a structure of knowledge and control

For Foucault, the discussion about sexuality is not one of freedom at all. We are even manipulated to talk about sexuality. The more we talk about it, the more knowledge we have about this subject, and the more knowledge there is available, the more power can be exerted on us. We do not talk about sexuality because we think we are free, but because it is expected from us (Wubbels, 2005). All this knowledge about sexuality also brought along what was seen as normal and abnormal sexuality.

The way sexuality is discussed is what Foucault calls the 'discours’. This can be defined as a construct of related concepts in which the world can be seen. So it creates a certain image of the world we live in. We connect all kinds of concepts to sexuality and relate this to different societal processes. The ‘discours’ creates power structures in society. Eventually, man will shape himself to fit in these power structures, which will form our sexuality (Schutijser, 2009).

Furthermore, the power structures we are a part of are not universal. Foucault’s concept ‘souci de soi’ describes the self-care of man. This self-care exists because, in principle, there is always a possibility to reach further than the current power structures and morality. This brings along the opportunity to form new identities. This means that we do indeed have the freedom to be different. We have the freedom to look differently at life and develop new identities, and Foucault says that creativity is essential in this respect. This freedom should be valued and used. The self-care of man is the care to cross the boundaries of power structures and universality claims, in order to find oneself (Donkers, personal communication, 2015).

When we look at Foucault’s findings, we can see that freedom has been decreased although we have the opportunity to be different. We adjust to the norms that rule society, because we do not want to be excluded, and think that these norms and power structures are normal. So you could say that we do not have our own identity and personality, as it is something mostly created from the outside.

Case Studies - Online Identities

Donald J. Trump

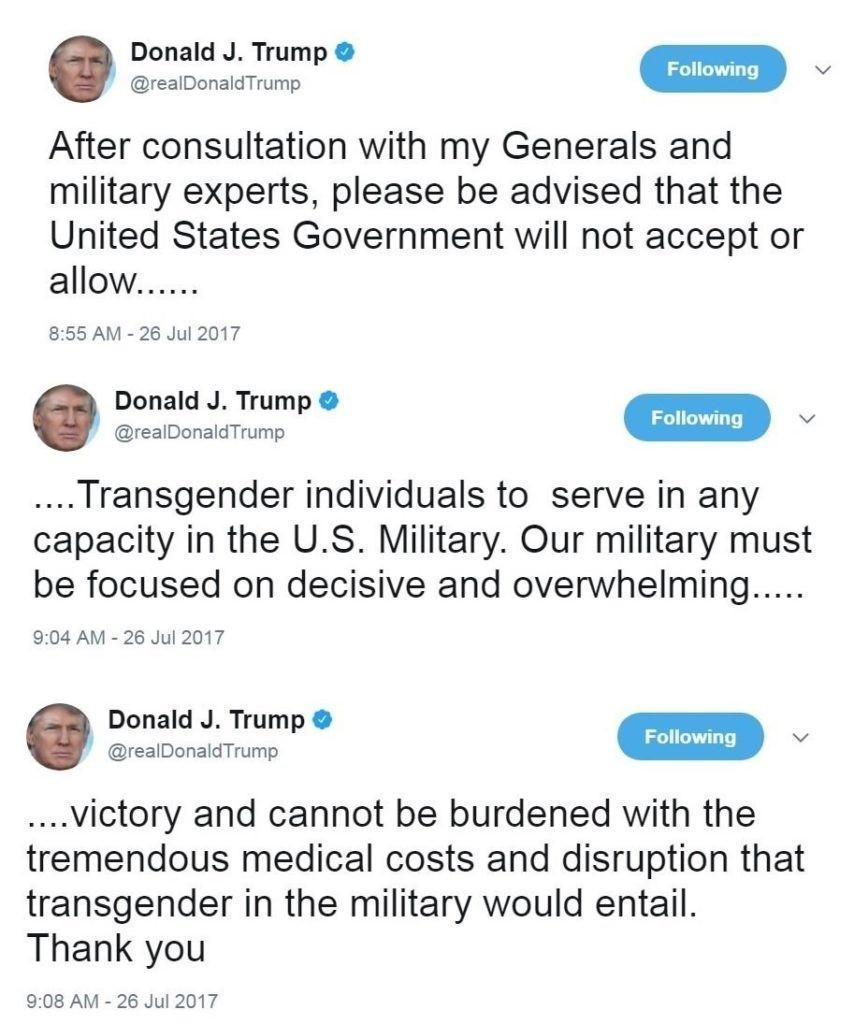

The 45th president of the United States seems to be very occupied with creating an online identity, especially on his Twitter account (Fig. 3). The persona he created doesn't just provide statements and opinions about how he sees life, but was also a vital element in his presidential campaign. He projects a Republican view on life and is often linked with the values of the alt-right. Moreover, his fame as a public figure seems to be influencing his online persona.

Fig. 3 Trump openly shares his thoughts on sensitive topics

If we look at Trump's online behaviour from the perspective of Sartre, we can see that this is someone who knows how to deal with his ‘freedom’ on the web. His decisions about what to share are not stopped by anything or anybody, he just says what he thinks is right. Concerning his power and wealth (something we will come back to later), he barely deals with any faculties. He decided for himself what kind of leader he wants to be.

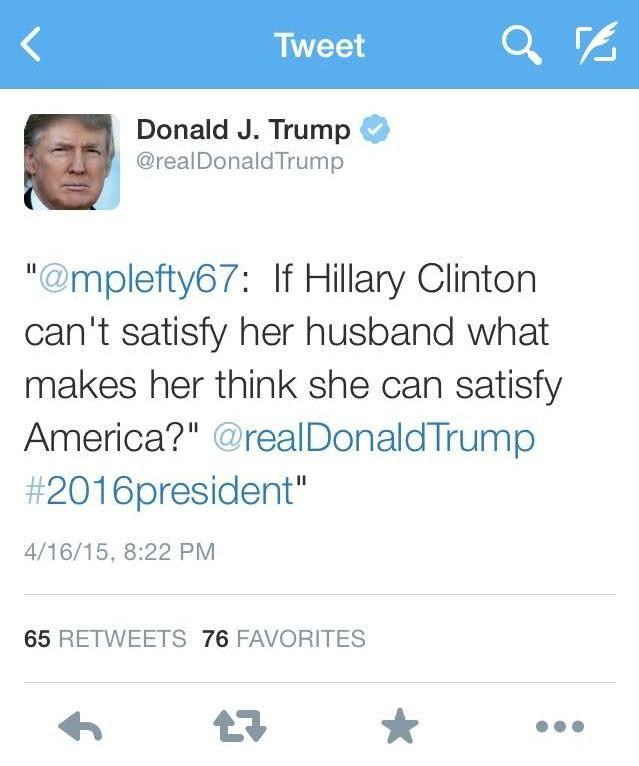

Regardless of being in the public eye, he shamelessly shares his thoughts, especially on Twitter (Fig. 4). He takes control of his own online personality, and that may have been what helped him win the elections (Maly, 2018). Trump filled in his personality with the things he supports and believes in. Although these things may not always benefit others, they are things that he as a president wants to stand for. Changing himself just for the pleasure of others, e.g. to be a more loved figure, would be living a lie anyways - mauvaise foi.

Fig. 4 Insulting others to get what he wants is not an issue for Trump

Does this mean that Trump just impulsively created this image of himself? Possibly. On the other hand, he is very aware that he is watched and that his actions have an influence on the world. As mentioned, his online persona played a crucial role in winning the elections. The way he used language and online media to relate to the crowd can be connected with Foucault’s idea of the panoptic society (Fig. 5). Trump knows he is being watched all the time, but instead of being influenced by the power structures around him, he takes matters into his own hands and uses this to strengthen his position.

He seems to have ’broken out' of prison, and is therefore not affected by movements towards normalization and disciplining, unlike most people. As a celebrity and millionaire, he has experienced neither punishment nor exclusion.

Most of us adjust to the norms that society offers us, because we do not want to be excluded. Unlike Trump, we think that these norms and power structures are normal. But he took control and now is in charge himself. This is an example of what Foucault calls ‘souci de soi’:the self-care of a man. The possibility to reach further than the power structures and morals, gave Trump the ability to form his own new identity, as the US president. However, Foucault connects this with the freedom to be different. In our opinion, Trump went even further than that and has become a power structure himself, as he imposes his morals on a large part of the Western society.

Fig. 5 Knowledge is power - knowing what you stand for can make you a president

Dalia Alfaghal

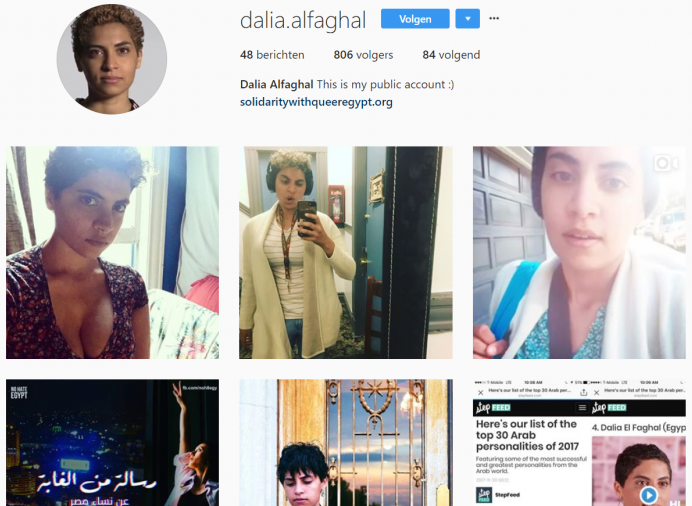

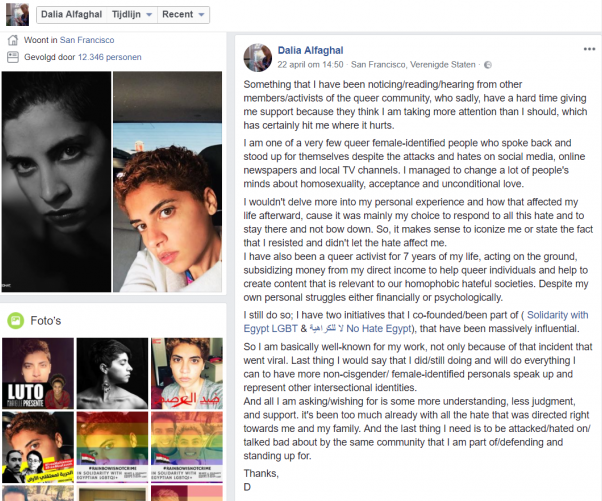

Dalia Alfaghal is an Egyptian female who came out as a lesbian on Facebook. Her post went viral and received a lot of critique from her fellow Middle Easterners. Following the incident, she has called herself 'the most hated lesbian in Egypt.' Since then, she has been very vocal online and has been involved in the LGBTQ+ community. She has also been featured on Buzzfeed LGBT, where her story reached millions of people.

Fig. 6 Dalia Alfarghal's Instagram profile

Dalia’s online presence embodies multiple concepts of Sarte's and Foucault's. Dalia represents Foucault’s ‘souci de soi’ principle, for example. By coming out in such a public and influential way, she has taken matters into her own hands and has formed her own identity, in spite of what norms her environment expected her to conform to. She clearly made use of the freedom to be different and her power to use creativity to deviate from current power structures that Foucault implies are present in society. She found that she needed to make a choice for herself and her own well-being, instead of simply conforming to societal rules..

Moreover, Dalia’s case could relate to Sartre’s concept of abandonment. She had an individual and personal dilemma, and could not rely on her environment, cultural values, religion or any other influences to help her with this decision. She had to trust her instincts, feelings and nothing else. She chose a path for herself, not one that was prescribed to her by any beliefs, morals or institutions.

The process after Dalia’s coming out has some characteristics that fit Foucault’s notion of sexuality. In our modern day society, talking about your sexual orientation as openly as Dalia has, is an increasingly popular phenomenon. Some taboos has been broken surrounding sexuality and sexual orientations other than being straight, and we have more knowledge about the subject. Dalia is a very active advocate for the LGBTQ+ community and enforces this phenomenon by sharing all there is to know about her sexuality on a regular basis.

Fig. 7 Facebook post by Dalia Alfarghal

She is also very determined to help as many people as possible to express themselves in the way that they identify themselves (she describes this goal in a recent post of hers, shown above). By doing so, she helps shape another one of Foucault’s concepts, namely that of normalization. More specifically, the normalization of the discussion around sexuality and the normalization of the sharing of information (and therefore the increase of power).

Our own profiles

We also create online identities. The things we decide to share and like are also often carefully chosen. What is immediately obvious when we look at our own profiles on social media platforms is that we keep information quite ‘private’ in comparison to the cases discussed above. For instance, all of us have a private account on Instagram and Facebook, which means the administrator of the account can decide who is allowed to see their content. In that way, we have at least some power over who gets the see the things we post, and therefore, diminish the feeling of a panoptic society. Despite being watched all the time, we feel like we have fewer obligations to justify our actions and posts on social media, because the people we allow access to our profiles are like-minded people.

When we look at the things we post online we see that there are certain things everyone shares. Graduating or getting your driver's license, for example We can link this to the concept of normalization. It is expected of us to share important achievements in life, because everyone does this; it has become the norm for social media. As soon as you do not share this kind of information, and rebel against the system, people will think you failed your exams. This will then lead to exclusion.

Fig. 8 Graduation and driver license Facebook posts

Moreover, we only tend to show the positive things online. We post pictures of our trips abroad, parties we attended and other fun events. This displays only one side of our personality, that which we like the most and want others to see. This can be related to the concept of 'mauvaise foi'. The sharing of good things and trying to show ourselves in a certain way is holding onto the picture of who we want to be, while this is not always the case offline.

Fig. 9 Ghyli and Julia's Instagram feed

Sartre and Foucault are still reliable

Theories on behaviour formed long before the social media era are still applicable today. In the span of few decades, considering the technological advances, people have not changed a lot. We are still influenced by certain things the society and our own lives, and these factors appear on modern day profiles as well. The components of identity construction described by Sartre and Foucault, such as 'souci de soi,' factualities, the panopticon etc. can be found not only in the examples we discussed but also in any random pool of social media accounts.

References

Donkers, N. (2015-2016). Notes on Philosophy about Free Will. Eindhoven, NL: Pleincollege Eckart.

Foucault, M. (2003). Abnormal, Lectures at the College de France, 1974-1975. London, UK: Verso.

Howells, C. (1988). Sartre: The Necessity of Freedom. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Maly, I. (2018). Nieuw Rechts, Uitgeverij Epo. Translated by us.

Sartre, J. P. (2007) Existentialism is a humanism. New Haven, CO - USA: Yale University Press

Schutijser, D. (2009). Vrijheid bij Sartre en bij Foucault. Published in: Wijsgierig.

Wubbels, E. (2005). Is praten over seks vrijheid? Nemo, Kennislink.