Protests in Bulgaria: "Mafia" Out

Bulgaria has not been untouched by the coronavirus. Covid-19 has destabilized the economy and the medical system and had serious consequences for people's mobility.

However, the country faces far more serious problems than the pandemic, as protesters have gathered on the streets of Bulgaria for more than four months with only one demand - to overturn the “corrupted” government. They want the resignation of the prime minister Boiko Borisov and the Chief Prosecutor Ivan Geshev. They claim to be tired of being ruled by a government that has no moral values and no interest in serving the nation. The government has been described as a “mafia” by the Bulgarian people.

This article offers a reconstruction of how the protests in Bulgaria became so powerful that they united the nation like never before and crossed the border to receive support from the rest of Europe.

A short history of the Bulgarian protests

Beginning in July 2020, a wave of protests emerged in Bulgaria. They have now broken the record for longest-lasting protest in the country, lasting 120 days as of November 5th, 2020. The protests are demanding an end to corruption and the resignation of prime minister Boiko Borisov and Chief Prosecutor Ivan Geshev. The Bulgarian people are using their constitutional rights, namely the right to free speech and the right to protest, to change the faith of their country. However, the idea of peaceful protesting was not enough to succeed.

Reports of police brutality have circulated in several Bulgarian newspapers and media channels. Many photos and videos have been shared on Instagram, Facebook, and YouTube as evidence of accusations against the police. On the night of July 10th, a protest in front of the Council of Ministers in Sofia escalated. Two men were dragged behind one of the building's pillars, where they were beaten unconscious (Figure 1). One of the men was 22-year old Evgeni Minchev, a law student in the Hague, the Netherlands. However, to the shock of everyone, the policemen were neither sanctioned nor removed from duty.

Figure 1: A scene from the police brutality against Evgeni Minchev.

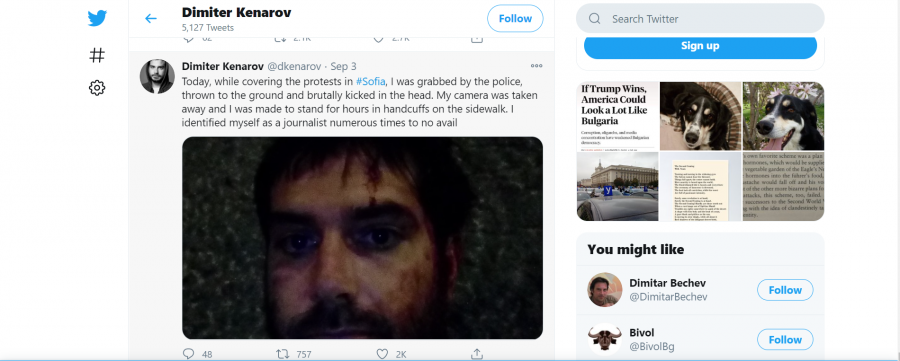

The police decided to use force against the protesters. Police also enacted violence against journalists and reporters, even when they identified themselves.

Dimitar Kenarov, a Bulgarian journalist, went on Twitter a day after the September 2nd protest, where he shared a photo of himself with the caption, “Today, while covering the protests in #Sofia, I was grabbed by the police, thrown to the ground and brutally kicked in the head. My camera was taken away and I was made to stand for hours in handcuffs on the sidewalk. I identified myself as a journalist numerous times to no avail” (Kenarov, 2020)(Figure 2). Thus, “after September 2, it is already clear that the Faculty of Journalism must introduce lectures on self-defense against police violence” ("Полицейско насилие и бой над журналисти на протеста", 2020).

Figure 2: The tweet of Dimiter Kenarov.

“The System Kills Us”

“The System Kills Us” is a Bulgarian political movement formed in 2015 by mothers of children with disabilities which forced the then Vice Prime Minister of Bulgaria, Valeri Simeonov, to resign (Lazarova, 2019). On September 16th, 2020, members of this movement gathered again at the National Assembly in Sofia, again demanding change. Mothers with their children in wheelchairs occupied the building from 10 a.m, stating they would not leave until they received the resignation of the government.

At 6 p.m. the National Guard began dragging the mothers and their children onto the street (Svobodna Evropa, 2020)(Figure 3). Maya Manolova, the former vice-chairperson, witnessed the events and said: “They pulled people out by force - by kicking, pushing, pushing” (Manolova, 2020), and stated that the children were denied visits to the restrooms in the building.

Figure 3: A photo of a mother from “The System Kills Us” who has been dragged by the police on 16th of September.

Bulgaria stands on the edge of a national crisis with waves of violence towards citizens and journalists erupting at every protest. The government is using all possible measures to silence the Bulgarian people, including using violence against children. Therefore, protesters have begun using social media to shift events in their favor.

Choreographing the protest

People used their social media profiles to create Facebook events to gather people for street protests (Figure 4). Gerbaudo describes the use of digital media to coordinate offline protests as the 'choreography of assembly'. Choreography of assembly refers to the "process of symbolic construction of public space, which revolves around an emotional scene-setting' and 'scripting' of participants' physical assembling" (Gerbaudo, 2012). The post seen in Figure 6 contains choreography of assembly as a link to the Facebook event is present (Figure 7).

Figure 4: A Facebook post about a protest in Plovdiv, Bulgaria.

This online social engagement is more than organizational. What we see happening is the construction of a public sphere in which different individuals voice their perspectives and take a position against others. By doing so they create a group identity and a discourse around (re)creating society. These citizens not only directly encourage people to join the cause but also try to trigger a reaction, from liking and sharing to hitting the streets. In addition to existing movements, common people are also now functioning as 'soft leaders' and contributing to the massiveness of the protests. Their calls to action on social media aim to convince people to fight for their cause (Figure 5).

Figure 5: A Facebook post from a Bulgarian civil activist.

As Gerbaudo stresses, affect is also crucial in mobilizing people. Bulgarian civil activists build their credibility by using emotional rhetoric in their messages and immersing themselves in the action, with the aim of gathering people around the topic and eventually the cause.

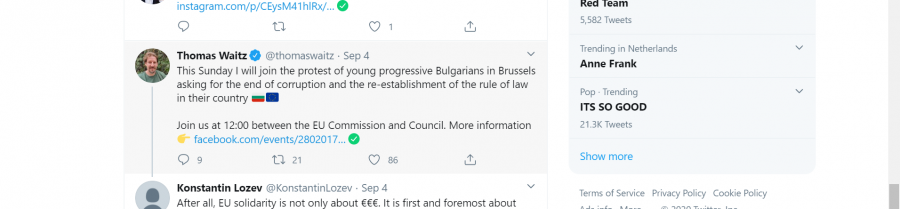

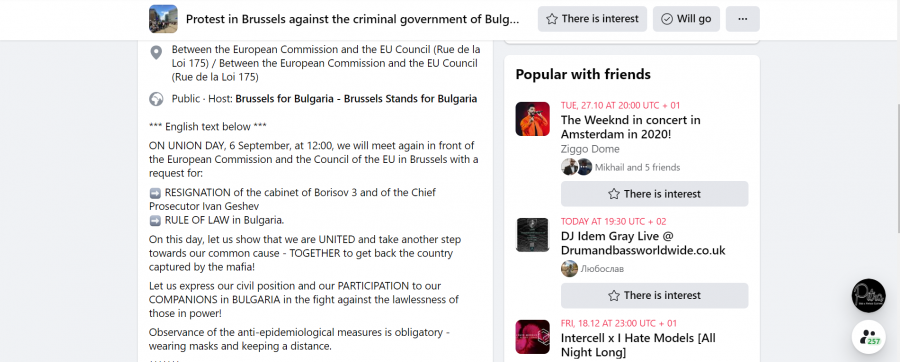

The organizing strategy of the “leaders” combined with the affordances of social media helped the movement gain popularity online and reach the rest of Europe. Small-scale protests in France, the Netherlands, Germany, England, and Brussels were organized in support of the protesters in Bulgaria and their cause. One of these occured on September 6th in Brussels. People who supported the cause went to Twitter to express their opinion and encourage others to join the gathering (Figure 6).

Figure 6: A tweet regarding the protest in Brussel on 6th of September.

It is not a surprise that tweets like this appear online since "modern media have always constituted a channel through which social movements not only communicate but also organize their actions and mobilize their constituencies" (Gerbaudo, 2012). Therefore, the role of social media in contemporary activism is vital because it helps organize actions quickly. As Gerbaudo states: "Social media can be seen as the contemporary equivalent of what the newspaper, the poster, the leaflet or direct mail were for the labour movement" (Gerbaudo, 2012). Thus, social media shapes how people come together and act in choreographed collective action.

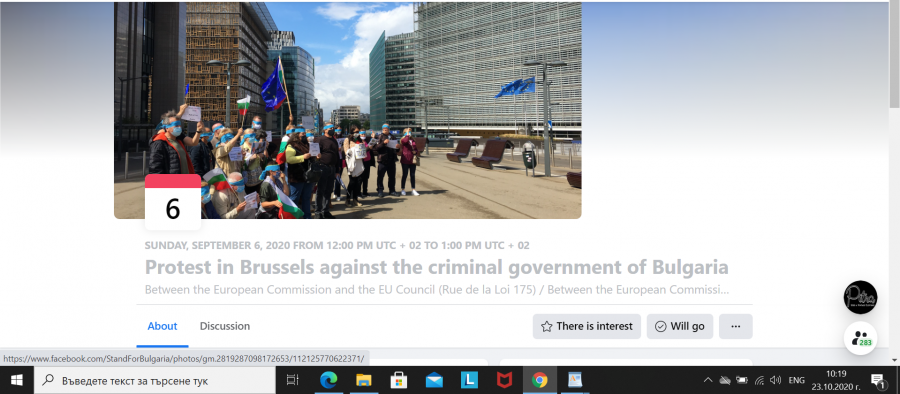

Figure 7: A Facebook event of the protest.

The page above provides information about the date, time, and location for people to gather under the slogan 'Brussels Stands for Bulgaria', displaying that "social media is directing people towards protest events" (Gerbaudo, 2012). However, the page also contains a description of the protest, containing the demands of the protesters and instructions on how to act (Figure 8).

Figure 8: The description of the protest.

Therefore, the protest can be successful not only if the people share the same final goal but also if the protestors behave in a certain manner. They have to be "united" and "together to get back the country captured by the mafia."

People use social media and the digital affordances that it offers not only to form and organize protests but also to create a specific behavioral norm by providing suggestions and instructions to construct “an emotional narration in order to sustain their coming together" in the public space (Gerbaudo, 2012).

Algorithmic activist

A key part of contemporary choreography of assembly is what Maly (2018, 2019) calls ‘algorithmic activism’: “This type of activism contributes to spreading the message of a politician or movement, by interacting with the post in order to trigger the algorithms of the medium, so that it boosts the popularity rankings of this message and its messenger” (Maly, 2019). Activists use their knowledge of the affordances and algorithmic construction of a certain platform to explicitly make their voice more visible and reach a bigger audience (Maly, 2019).

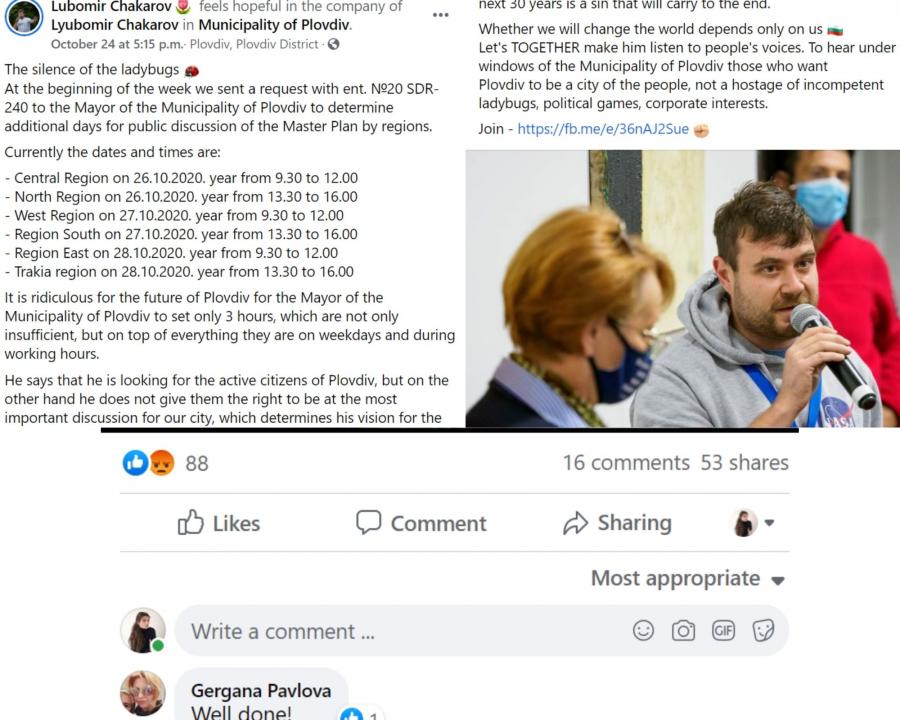

Lyubomir Chakarov is a political activist who has been the main organizer behind protests in Plovdiv, Bulgaria. He began constructing his activism around the slogan “ladybugs out,” 'ladybugs' referring to the government and Municipality of Plovdiv (Figure 9).

Figure 9: A Facebook event from Lyubomir Chakarov about a protest in Plovdiv.

He even created his own logo - a ladybug with the word “вън”, which translates into “out.” One of his first posts in which he uses the term had 53 shares, 16 comments, and 88 reactions, which is double his previous engagement (Figure 10).

Figure 10: One of the first Facebook posts of Chakarov, where he uses the term ladybugs.

After seeing that this slogan boosted his visibility on the platform, he continued using it either as a logo or in text. Therefore, Chakarov used his “intentional” discovery to trigger Facebook's algorithm, popularizing his voice on the platform and helping his “ladybug” activism reach a broader audience.

Bulgaria as member of the European Union

Even though the protests in Bulgaria received a large media scope and support, their desired changes did not materialize. They therefore decided to change their strategy by seeking actions from Germany and Belgium. Protests in front of the German Embassy in Sofia were organized, demanding Berlin and Brussels “open their eyes” to the corruption in Bulgaria (AP News, 2020). The protesters held posters depicting closed eyes and the word “Blind”, as well as golden stars while blindfolded (Figures 11 & 12).

Figure 11: A poster from the protests in front of the German Embassy in Sofia, Bulgaria.

Figure 12: Protesters in front of the German Embassy holding golden stars with closed eyes.

Their message aimed to provoke the European Union to stand behind the values they promote and the laws they apply, as the Bulgarian people do not see these morals and rules being implemented by their government. They argue that Bulgaria has failed to be a worthy member of the union and demand EU intervention.

The European Union took the call from the Bulgarian people and paid attention to the situation in the country. However, they decided to not take action because it is a matter of current affairs in the country, and there will be elections for a new government in March.

Conclusion

Contemporary protests, movements, or activism are never fully offline or online. To achieve their desired outcomes, they operate in both places at the same time. Digital affordances offer organizers enormous accessibility to millions of people around the world that could help push for change.

Just as corrupt political powers used all measures necessary to demolish the movement, the protesters used every tool available to achieve their final goal. The leaders of the Bulgarian protests used the affordances of Web 2.0 to mobilize people, gain visibility, and implement algorithm activism as part of their online strategy. Furthermore, these affordances allowed them to create specific behavior and tell their story in a specific manner, allowing them to put all European eyes on Bulgaria, even at the level of the European Union.

Even though the wave of protests across Bulgaria has led to political instability, it has united the Bulgarian people more than ever. Still, the Bulgarian government continues to refuse to meet the demands of protesters, however, the people will not lose heart.

References:

Bond, B., & Exley, Z. (2016). Rules for revolutionaries (pp. 1-10).

Bulgaria: Protesters seek support from Berlin and Brussels. AP NEWS. (2020).

Gerbaudo, P. (2012). Tweets and the streets. Pluto.

Maly, I. (2019). Algorithmic populism and algorithmic activism. Diggit Magazine.

Lazarova, A. (2019) The battle of 'The System Kills Us' against Valeri Simeonov. Diggit Magazine. (2020).

"Бийте ги, докато им сложат белезници". СЕГА. (2020).

"Позор, Караянчева". НСО изведе със сила от парламента хора от "Системата ни убива". Свободна Европа. (2020).

"Полицейско насилие и бой над журналисти на протеста". Площад Славейков. (2020).

"Протест в Брюксел срещу престъпното управление на България". Facebook.com. (2020).