Soccer: A Society’s Reflection of Gender Equality

In soccer, gender inequality has the status of common sense. Traditionally, disparity in monetary rewards and employment conditions between male and female soccer players is considered to be quite normal. However, recently the Norwegian Football Association (NFA) announced that it has reached a new collective agreement, stating that players of the women’s national soccer team will be paid the same as players of the men’s national soccer team (Reuters, 2017), which is a big step forward in the fight for equal rights.

Soccer, gender equality and the pay deal

Starting in 2018, players of the Norwegian women’s national soccer team will be paid equal to players of the men’s national soccer team (Reuters, 2017). The men will divide a portion of their income from commercial activities to the women; this means that the compensation for national games is equal. Besides, the NFA will double its fixed payments to the women’s national team. Before this new agreement, players of the national team needed to study or work besides soccer and this affects their performance, undoubtedly (Payne, 2017). "Norway is a country where equal standing is very important for us, so it is good for the country and for the sport," says players' union boss Joachim Walltin.

Rules and regulations are no longer set within four walls and this news rapidly traveled to every corner of the globe. As a consequence of globalization it became possible for female soccer players all over the world to consider equal rights. Subsequently, many female soccer players have come to action, including Vivianne Miedema (player of Arsenal and the Dutch women’s national soccer team). “We put in the same effort – we deserve the same pay” she said to The Guardian. Is it reasonable to assume that the Norwegian pay deal affects the financial conditions of the Dutch women’s national soccer team as well?

Gender inequality is embedded in most organizational structures and is therefore institutionalized. However, this probably does not apply in Norway, as diversity is institutionalized, instead of gender inequality.

We observe that there is a different, i.e. unequal position for men and women in the world of soccer. However, the way one assesses and evaluates male and female sports may vary widely among nations (Broch, 2016). The aim of this article is to explore the relationship between women’s soccer and gender equality in a globalized world and examine their possible effects on the transferability of the Norwegian pay deal to the Netherlands.

This article first considers the development of women’s soccer from a global perspective, and examines how it corresponds with theories of gender equality in general. Then it focuses on the local perspective of gender equality and its influence on women’s soccer in both Norway and the Netherlands. Finally it examines the influence of globalization on this specific case.

Gender stereotyping

The term gender inequality refers to the idea and situation that women and men are not equal and thus not have equal rights (Parziale, 2008). Heilman (2012) provides a meaningful contribution with the theoretical approach to gender stereotyping which stresses the fact that there are generalizations about men and women that are applied to individual group members just because they belong to this specific sex.

Additionally, this article elaborates on the theory of gendered organizations from Acker (1990), in which she states that organizational structures are not necessarily gender neutral and that gender inequality is part of the structure of society at a fundamental level. Gender inequality is embedded in most organizational structures and is therefore institutionalized. Acker found that “the gender segregation of work, including division between paid and unpaid work, is partly created through organizational practices” (1990, p. 141).

Due to new technologies, mass mobility increased in speed and volume and thus opinions and knowledge are quickly spread among a large audience, a pattern that also occurred in this specific case. Therefore, this article will as well examine this part of the transferability by using Appardurai’s (1996) culture scapes, in which he describes several fluid dimensions that contribute to the global exchange of ideas and information. These dimensions create new realities that decrease the differences between different groups and cultures.

How women’s soccer is constructed in present times is influenced by historical events. In order to understand the current situation, it is crucial to take the historical context in which this developed into account. Therefore, the next section will give a brief overview of the development of the contemporary situation of women’s soccer.

Soccer, it’s a men’s game

Gender inequality in soccer goes back to the beginning of the 19th century. Due to the industrial revolution, a great number of men left the villages and went working in the big cities. Prange and Oosterbaan (2017) found that people were afraid that, as a consequence of the absence of men, the young boys would grow up too feminine. This led to the popularity of a sport like soccer: masculine, rough, physical, and strengthening brotherhood. Soccer could give the boys the masculinity they needed; at least that was the assumption (Prange and Oosterbaan). Besides, there was a predominant idea that soccer was dangerous and caused damage to a woman's organs. According to Parziale (2008), this biological argument of gender inequality used to be very common.

Soccer game between West Germany and the Netherlands

The logical consequence of these developments was that women were not allowed to play soccer at that time and thus women’s soccer, both within and across countries, has been significantly underdeveloped in comparison to the men’s game (Skogvang, 2007). Subsequently, men’s soccer has become the norm and Heilman (2012, p. 113) describes this as follows:

“Gender stereotypes promote gender bias because of the negative performance expectations that result from the perception that there is a poor fit between what women are like and the attributes believed necessary for successful performance in male gender-typed positions and roles.”

As a result there is a negative expectation of women’s soccer because the expectations are based on the men’s norm whereas women’s soccer cannot always meet this standard. Therefore, it is not self-evident that women’s soccer evolves to an equal position. However, soccer can be seen as a cultural expression of a society (Claringbould and Knoppers in Prange & Oosterbaan, 2017), and therefore it is important to take the country-specific cultural context into account when analyzing soccer on a national level.

The feminist wave and its influence

When in the beginning of the 19th century women’s soccer made its advance in Norway and the Netherlands, the public opinion was not half as positive as it is today: both countries were fed up with setbacks due to the dominant view that soccer was a sport for men (Skogvang, 2007). It was during this time that the first bricks towards gender inequality in soccer were laid, and this did not bring positive developments for women’s soccer. However, towards the end of the 1960s, both women’s movements in Norway as well as in the Netherlands experienced a great amount of progress.

Scientist Joke Kool-Smit (Meijer, 1996) found that a woman's identity is partly derived from that of her husband and these findings caused awareness among Dutch women. They experienced a growing dissatisfaction because of the predominant idea that women got fulfillment from what her husband and children achieved and as a consequence there was a strong need to self-development and the urge among women to participate in the society (Bussemaker, 1992). The women’s movement aimed to increase the participation of women in the labor process in order to enhance economic independence across women and to create equal positions in society (Meijer, 1996).

Around the same time, a similar movement arises in Norway, where women fought for equality for men and women:

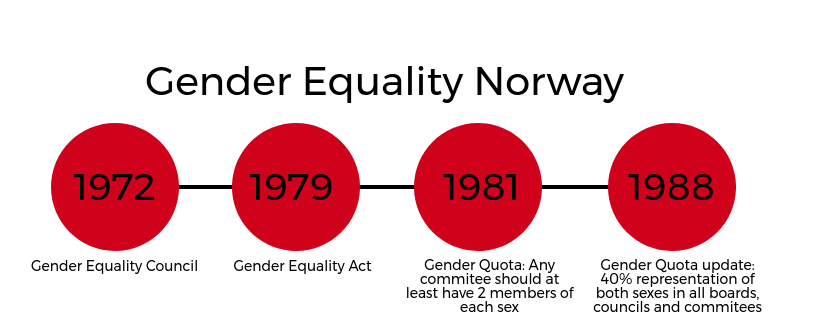

"The Gender Equality Council was established in 1972 and in 1979 the Gender Equality Act came into force to strive to achieve gender equality in Norway. The Nordic philosophy of equality stresses that equal opportunity is not enough and that active efforts are required to promote the status of women.'' (Skogvang, 2007, p. 44)

The figure below shows four key moments in women’s development in Norway.

Key Moments Gender Equality Norway

Professionalization and diversity

In Norway these developments, among other factors, had an impact on the evolution of women’s soccer: in 1984 a women's soccer committee was set up to focus on the professionalization and development of women's soccer. They ensured that coaches, managers and referees were trained and that there would be better cooperation within the union. Consequently, more tournaments for women were organized. In addition, the committee ensured gender diversity within boards of the union and other important soccer corporations (Welten, 2015).

According to Acker (1990), gender inequality is embedded in most organizational structures and is therefore institutionalized. However, this probably does not apply in Norway, as diversity is institutionalized, instead of gender inequality. In addition, in 1991, the NFA made more funding available for the professionalization of the Norwegian women’s teams. This funding supports the Norwegian women’s national soccer team in hiring a professional who focuses on the commercialization of women’s soccer (Welten, 2015). Consequently, the income of the Norwegian women’s soccer has increased with 45% in the period of 2006 to 2009 (Skogvang, 2013). The experienced increase in the wages supplied by the clubs has decreased the women’s dependence on the wages received from the national soccer federation.

It is important to note here that the national soccer associations, such as the Dutch Koninklijke Nederlandse Voetbalbond (KNVB) and NFA, have the exclusive right to grant licenses for tournaments. Besides, there are no regulations whether associations must compensate national-team players or even cover their expenses. This implies that the national teams depend fully on the regulations and agreements supplied by their national soccer associations (Prange & Oosterbaan, 2017).

Leading on the field but not in the helm

The women’s movement in the Netherlands also had its effects on women’s soccer: in 1971 women's soccer was officially recognized by the KNVB and a women's soccer association was established. As of 1979, it became possible for girls to become a member of the KNVB and in 1986 mixed soccer became allowed. As a consequence, women could now join existing soccer clubs (Prange & Oosterbaan, 2017). However, the women’s movement in the Netherlands did not ensure a gender neutral organizational structure. Consequently, the policymakers still are mostly men. According to Acker (1990), this might lead to a gender segregation of work including the division between wages. This corresponds with the conditions of the national women’s team from the Netherlands (Elhage, in Prange & Oosterbaan, 2017):

- A Dutch paid women’s division started in 2007 but the board can repel the women´s divisions in case of disappointing earnings,

- Joining one of the paid associations means the players receive a player contract instead of an employment contract. This means that, instead of paying the minimal wage, the association can provide the players with an expense allowance which is around 600 euros a month,

- This player contract offers minimal legal protection.

Additionally, the widespread idea that the earning of the women’s national soccer team should be based on the offer and demand continues to exist, as can be illustrated by an episode of Studio Voetbal Sunday 19th of November on Dutch television. In this episode Tom Egbers asked his four guests about their opinion, which is unanimous: The Dutch national women's soccer team should earn more than they do now, but their rewards should mainly be based on offer and demand.

There is a limitation to this approach, however. It is likely that the women’s national soccer team would earn more money if they were able to professionalize and commercialize themselves, albeit as they receive no financial support from the KNVB, this is less likely to happen. As a result, the Dutch national soccer team finds itself in a vicious circle: the women need to professionalize and commercialize in order to earn more money, but as wages are not high enough, players need to keep studying and working in order to maintain themselves. This undoubtedly affects their performance and leaves no time left to professionalize.

Taken together, these results suggest that there is a difference between women’s soccer in the Netherlands and Norway and one of the factors that has established this difference is the different reaction to the women’s development and, consequently, the institutionalization of gender equality. In Norway, the organization structures are gender neutral and gender equality is part of the structure of society at a fundamental level, whereas in the Netherlands gender inequality is institutionalized in women’s soccer which might lead to gender segregation in employment and a resulting difference in levels of earning. Therefore, the approach of Acker would lead to the conclusion that the transfer of the pay deal to the Netherlands is unlikely to happen.

However, a drawback of this approach is that it takes both countries to be static in nature rather than hybrid, whereas hybrid dynamics allow ideas, goods and people to rapidly cross traditional borders.

Women’s soccer in a globalized world

Appadurai (1996) found that globalization is a manner of creating several fluid dimensions that contribute to the global exchange of ideas and information, i.e. ethno-scapes (movement of people), media-scapes (movement of media), techno-scapes (technological development creates boundaryless environments) , finance-scapes (movement of money), ideo-scapes (movement of political ideas). These dimensions create new realities that decrease the differences between different groups and cultures.

Media all over the world reporting the Norwegian pay deal

New technologies increase the mass mobility of ideas, as happened with the local Norwegian pay deal since the idea was rapidly transferred to other sides of the globe as can be seen in the image above. It became a global phenomenon as well, and enabled both national women's soccer teams as well as societies to consider the rights of the soccer players. Consequently, many women have come to action, including the Dutch national women’s soccer team.

"We put in the same effort - We deserve the same pay"

However, the idea initially received little support, there was still a predominant idea that women should not earn as much as men as they are assumed to not bring in as much as the men’s national soccer team. Nevertheless, the demand of the women’s national soccer team got more and more media and public attention and again, the big differences between wages of the men’s and women’s national soccer team became a subject of public discussion. The Norwegian pay deal and their beliefs about equal payment gradually made their way into the Dutch society and as a consequence there came a counter movement to existence that actually wants the Dutch women's national soccer team to have more monetary rewards and better conditions. It is reasonable to conclude that globalization affects the possibility to transfer the Norwegian pay deal to the Netherlands in a positive way, but it might be to premature to state that this will happen in the exact same way.

Women’s soccer: the global phenomenon with local features

In this article the aim was to assess the possibilities to transfer the Norwegian pay deal to the Netherlands in which we looked at the intersection of globalization, gender and women’s soccer. Looking from the gender perspective, this study has led to the conclusion that it is not likely that this pay deal will be transfered to the Netherlands because of the institutionalized gender inequality in Dutch women’s soccer: there are no women in the boards, the women do not have legal protection and they do not even have a legal collective labor agreement. However, a limitation of this approach is that it only focuses on one particular perspective i.e. gender (in)equality, and it assumes both countries to be of static nature, consisting of solid boundaries, whereas globalization typically softens or erases those boundaries.

Globalization enabled the national soccer team to spread their demands for equal pay which raised a new public debate about the women’s conditions and rights. The local Norwegian phenomenon got global features and moved to other parts of the globe, but then it was embedded in a new culture and society again i.e. the Netherlands, and the local criteria and norms define the process of change (Blommaert, 2010). This said, we might conclude that on the intersection of gender, globalization and women’s soccer we must assume that the KNVB might overlook the rights and conditions of the women players, albeit it is not likely that the Norwegian pay deal will transfer to the Netherlands in its contemporary state considering the institutionalized gender inequality in Dutch society.

A noteworthy fact to mention is that on the 12th of December, 2017 the KNVB announced that there will be new financial conditions for the Dutch women's national soccer team. This stresses the fact that in a global world the development of internationally-oriented phenomena goes faster than writing this essay. Read the article here.

References

Acker, J. (1990). Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations. Gender and Society, 4(2), 139-158.

Arjun Appadurai (1996), Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. (pp. 1-13)

BBC. (2017, 8 October). Norway will pay their male and female football teams the same

Blommaert, J. (2010). A critical sociolinguistics of globalization. In A Sociolinguistics of globalization (pp. 1-28).

Broch, T. B. (2016). Intersections of Gender and National Identity in Sport: A Cultural Sociological Overview (Sociology Compass).

Bussemaker, J. (1992), “Feminism and the welvare state: on gender and individualism in

the Netherlands”, History of European Ideas, 15 (4-6):655-661. DOI: 10.1016/0191-6599(92)90075-N

Heilman, M. E. (2012). Gender stereotypes and workplace bias. Research in Organizational Behavior, 32, 113-135.

Meijer, I. C. (1996). Het persoonlijke wordt politiek. In I. C. Meijer (Red.), Persoonlijke wordt politiek (pp. 2-17). Amsterdam, Nederland: Het Spinhuis.

Parziale, A. (2008). Gender Inequality and Discrimination. In R. W. Kolb (Red.), Encyclopedia of Business Ethics and Society (pp. 978-981).

Payne, M. (2017, 8 oktober). Norway to pay men’s and women’s soccer teams equally after men agree to slight pay cut. The Washington Post.

Prange, M., & Oosterbaan, M. (2017). Vrouwenvoetbal in Nederland. Utrecht, Nederland: Klement.

Reuters. (2017, 7 oktober). Norway FA agrees deal to pay male and female international footballers equally. The Guardian.

Skogvang, B. O. (2007). The Historical Development of Women's football in Norway: From 'Show Games' to International Successes. In J. Magee, J. Caudwell, K. Liston, & S. E. Scraton (Reds.), The Historical Development of Women's football in Norway: From 'Show Games' to International Successes (pp. 41-53).

The Guardian. (2017, 17 november). Vivianne Miedema: ‘We put the same effort in – we deserve the same pay’.

Welten, M. (2015). Vrouwen al wel aan de bal, nog niet aan het roer.