The bilingual Google Assistant: breakthrough or cause of inequality?

Due to globalization, families are likely to speak multiple languages within one household. That is why the Google Assistant is now bilingual. Is this a breakthrough in the super-diverse world or just another cause of inequality?

The bilingual Google Assistant

On August 30, 2018, Google announced that their Google Assistant becomes bilingual (Google AI, 2018). The Google Assistant itself was released by Google in 2016 and is a “voice-controlled smart assistant”, which answers all the questions someone asks after saying “OK Google” or “Hey Google”.

Additionally, it is the first smart assistant that adds a bilingual feature, which means that it will respond to two different languages without switching the language settings of the application (Google AI, 2018). It was developed to make the use of it easier for multilingual households. Today, Google Assistant’s bilingual function is available in, and will understand any pair of languages with, English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, and Japanese.

However, more languages are expected to be launched within the coming months (Moore, 2018). Google’s introduction video as seen below, shows the different possibilities of the new bilingual feature.

However, can we say that the bilingual feature of the Google Assistant is applicable in our current super-diverse society? To answer this question, we looked into relevant literature and subsequently asked a frequent user of the Google Assistant about his experiences with the bilingual feature. The respondent has been using the assistant for two years now, which means he has experienced the recent development of the product. He even decided to integrate the features of the Google Assistant in his new house (e.g. automatically switching off the lights and television).

Society in motion

Due to new waves of migration and transnational movement, countries nowadays cannot be characterized as merely diverse; rather they have become super-diverse (Vertovec, 2007; Blommaert, 2010). As a consequence, people living in a specific country should no longer be associated with a single specific group, identity, or language (Spotti & Blommaert, 2017).

On the contrary, multilingualism, the social situation in which two or more languages are used, has become a well-known condition for the majority of the world population (Romaine, 2006). For instance, 16 percent of all the couples in the Netherlands consists of at least one person with a migration background (CBS, 2017), probably resulting in a multilingual household.

Taken together, the first bilingual version of Google Assistant is a useful upgrade of Google's former version of its assistant and is appropriate in the contemporary time of growing multilingualism.

Not everybody's cup of tea - inequalities are coming along

However, it should be acknowledged that the bilingual Google Assistant is not accessible for every multilingual household, since certain skills and products are needed to make use of its benefits. Primarily, households have to be in the possession of at least one mobile phone and they need to have access to the internet. Additionally, they need to know how to use the Google Assistant, meaning they need the right e-literacy to be able to make use of the application.

The right e-literacy is necessary to make use of the products that come along with digitalization.

This connects seamlessly with Pachler, Cook, and Bachmair’s (2010) theory about e-literacy, which states that the need of the right e-literacy is necessary to make use of the products that come along with digitalization. The person we interviewed agreed on this and stated the following:

“The Google Home assistant is not everybody's cup of tea. But for the younger generations it might be taken for granted and they will think it’s weird when somebody does not use the assistant. But when I reflect on my own generation (25 years and older), not everybody is jumping of excitement about this new technology”. (Personal Communication, October 3, 2018).

Moreover, Blommaert (2010) argues that the majority of the world’s population still does not have access to the new technologies that offer “shortcuts to globalization, they live, so to speak, fundamentally un-globalized lives; but the elites in their countries have such access and use it in the pursuit of power and opportunities” (p. 3) and this does have an effect on the ‘un-globalized’ people in a country.

Taking the Google Assistant as an example, this notion becomes important as well since it is exclusively available for globalized and e-literate households, which causes new inequalities between the un-globalized and globalized multilingual households.

The big six

Not only the need of certain skills and products cause inequality. The bilingual version of the Google Assistant is only available in six languages (English, Spanish, German, French, Italian, and Japanese), which impacts the target group as well. How could Google's language choice be explained?

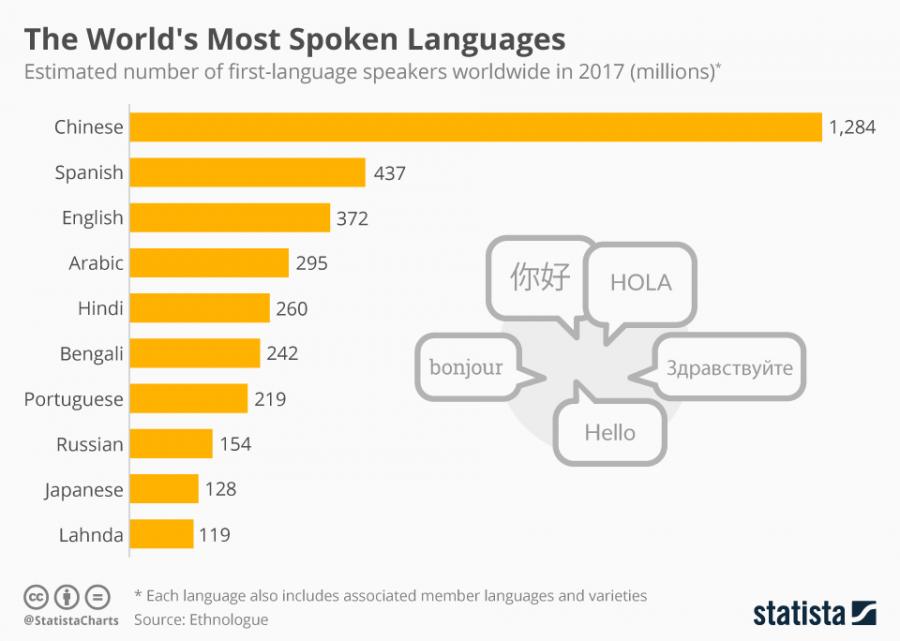

Firstly, Google might have chosen to integrate languages with a lot of speakers around the world. Notable is the absence of languages such as Mandarin Chinese, Russian, Hindi, Bengali, Portuguese, and Arabic, whilst languages with less speakers like Italian, Japanese and German are included.

The World Most Spoken Languages

A second possible explanation for Google’s language choice could relate to the capital that the languages hold. Bourdieu (in Silver, 2005) explains this by using the notion of symbolic capital that shows that the normative standardized language is thought of as the legitimate language, because it is bound up with the state, and that all languages are measured against the practices of those who have power. English, Spanish, German, French, Italian, and Japanese do all carry capital and power (Lyons, 2017a; Lyons, 2017b; Lyons, 2018; Wood, 2017; Devlin, 2018; Vistawide, 2015).

Sociolinguistic point of view or the public opinion?

As described so far, the first bilingual version of Google Assistant is a useful upgrade and it surely takes the changing society in consideration, but it must be acknowledged that it might also create inequalities.

Nevertheless, it should be recognized that these inequalities are mostly related to the sociolinguistic perspective. This does not necessarily mean that the larger public agrees on this as well. Therefore, this section looks at the public discourse activities as they evolve in the comment sections of YouTube and Twitter (by the means of hashtags #GoogleAssistant and #Bilingual) and the opinion of our respondent.

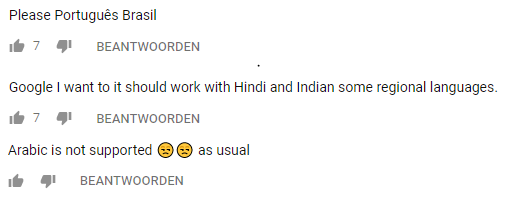

The introduction video on Google’s YouTube account has 1,9K likes (September 20, 2018) in comparison to 143 dislikes (Google, 2018). Within the comment section there is more dissimilarity in views: one party indicates to be positive about the innovation, another party indicates that there are still some improvements to make for Google, i.e. adding new languages and better implementation of the new bilingual feature, and yet another party indicates to be negative towards the new innovation.

However, the first two groups are significantly bigger than the third group, indicating a positive response towards Google’s new innovation.

Comment Section Youtube´s Introduction Video (positive)

Comment Section Youtube´s Introduction Video (new language suggestions)

Studying the hashtags #GoogleAssistant and #Bilingual on Twitter indicates some similar discursive activities. More than half of the tweets that include both the hashtags are relatively neutral, which means they have a journalistic tone of voice and include a link to a news article with more information about Google’s bilingual assistant. The other tweets indicate a positive attitude towards the new innovation.

Positive tweets with #GoogleAssistant and #Bilingual

These results suggest a slightly positive discourse towards Google’s new innovation, although people are critical about the languages available and the actual applicability and workability. This matches the opinion of the interviewee as well:

"It's a new technology, so I'm sure there are still a lot of things to be added and that is why I cannot mention any immediate downsides. The only thing that strikes me is that the Google Assistant needs a little longer time to answer a bilingual question." (Personal Communication, October 3, 2018).

Neutral tweets with #GoogleAssistant and #Bilingual

This rather positive discourse can be explained by the fact that again people who benefit least from the Google Assistant, might not even have access to new technologies. They are not aware of this new innovation and hence it is not likely that they have a negative feeling towards it either. Even if they have an opinion about the new function of the Google Assistant, they cannot take part in the discursive practices online because they do not have the so-called ‘shortcuts to globalization’.

Google's new innovation - The final judgement

The first bilingual version of Google Assistant is a useful upgrade of Google's former version and it definitely responds to the new structures within society. But even though the bilingual Google Assistant is fitting in modern society, we do argue that some of its aspects cause inequality and therefore need improvement.

Firstly, multilingual households need to possess certain products and, more importantly, the right e-literacy before being able to use the assistant. But even then, not every household can use the assistant, since only six languages are available. Notable is the absence of languages spoken by a larger group of people than for instance Japanese, German, and Italian. Adding Mandarin Chinese, Russian, Hindi, Bengali, Portuguese, and Arabic as the next languages could increase the number of users massively.

The discourse on YouTube and Twitter reflect our two main points of critique and are supported by our interviewee as well. In conclusion, the bilingual Google Assistant is a welcome innovation that needs some finetuning in order to be fitting in our super-diverse society.

References

Blommaert, J. (2017). Durkheim and the Internet: On Sociolinguistics and the Sociological Imagination. London, England: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Blommaert, J. (2010). The Sociolinguistics of Globalization (Cambridge Approaches to Language Contact). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511845307

Blommaert, J., & Spotti, M. (2017). Bilingualism, Multilingualism, Globalization, and Superdiversity: Toward Sociolinguistic Repertoires. In O. Garcia, N. Flores, & M. Spotti (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society (pp. 161–179). Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

Devlin, T. M. (2018, May 3). How Many People Speak German, And Where Is It Spoken?

Google. (2018, August 30). Google Assistant: your bilingual Assistant. Retrieved September 20, 2018

Google AI. (2018, August 30). Teaching the Google Assistant to be multilingual.

Lyons, D. (2017a, April 19). How Many People Speak Spanish, And Where Is It Spoken?

Lyons, D. (2017b, July 26). How Many People Speak English, And Where Is It Spoken?

Lyons, D. (2018, January 10). How Many People Speak Italian, And Where Is It Spoken?

Moore, C. (2018). Google Assistant goes bilingual, lets you speak two languages interchangeably.

Pachler, N., Cook, J. and Bachmair, B. (2010) Appropriation of mobile cultural resources for learning. International Journal of Mobile and Blended Learning, 2 (1). pp. 1-21. ISSN 1941-8647

Silver, R. E. (2005). The Discourse Of Linguistic Capital: Language And Economic Policy Planning In Singapore. Language Policy, 4(1), 47-66.

Vistawide. (2005). Top 30 Languages by Number of Native Speakers.

Wood, E. M. (2017, March 13). How Many People Speak French, And Where Is It Spoken?