Vietnamese Water Puppetry as an example of intermediality through the integration of multiple art forms

Using the water surface as a stage, Múa Rối Nước or water puppetry is an exclusive artistic heritage imbued with nuances and culture of Vietnam through the harmonized interplay of sculptural craftsmanship, puppetry, music, storytelling and religious beliefs. In this article, the case study of Thăng Long theater, one of the oldest and biggest water puppet theaters in Vietnam, will be used to demonstrate how Water Puppetry exemplifies intermediality and multimediality concepts.

Water Puppetry

The silhouettes of ancestors

Since the 1000s in Vietnam, the recording of historical events has been conducted by carving on large stone steles and erecting them in the courtyard of the king's palace. Based on different research approaches and sources, historical evidence of water puppetry was discovered on a Sùng Thiện Diên Linh stone stele which was placed at Long Doi pagoda in Ha Nam province of Vietnam. The stone stele states that water puppetry was born in the 1100s under the Ly dynasty (Nhà hát Múa rối Thăng Long, 2021).

Sùng Thiện Diên Linh stone stele has been marked as a national treasure since 2014

Why water?

In an agricultural country with a long-standing wet rice culture, combined with natural conditions of the tropical weather and a rich river system like Vietnam, water has become a symbiotic factor. The belief in the divinity of the water god is passed on from generation to generation in Vietnamese folklore. Initially, farmers played the water puppets at religious festivals and during worship rituals at the village halls. The water puppet show is a prayer to the water gods for protecting the fields from severe flooding and a call for bountiful harvests (Khê & Wehle, 1985).

During the period of the 11th to the 18th century when the wet rice industry was still not mechanized and modernized, water puppetry was a lucky charm of the farmers because of the belief that this religious art would help them to increase production (Nhà hát Múa rối Thăng Long, 2021). Yet from the second half of the 19th century until the beginning of the 20th century, under the yoke of French colonialism, water puppetry was despised and fiercely opposed as it was considered to be “superstition” (Nguyễn, 2019). The artists were arrested and killed, the artifacts were destroyed and the stage was burned so that people no longer dared to perform publicly. In spite of this, water puppetry still had a special place in the heart of Vietnamese society and in the thought of the patriotic Confucianists, who saw the puppets as the silhouettes of ancestors. In 1954 when the North of Vietnam was liberated, Vietnamese professional puppetry theater was officially born under the jurisdiction of President Hồ Chí Minh and received its status as a national form of theater art in 1956 (Phạm, 2023).

Into Thăng Long theater

Thăng Long Water Puppet Theater attracts a great number of international tourists to visit everyday

Thăng Long has played an indispensable role in the growth of Vietnamese water puppetry and in reshaping traditional spiritual customs into a modified form of musical performance that appeals to contemporary tastes and modern social contexts.

In order to explore the relationship between water puppetry and the concepts of intermediality and multimediality, The Thăng Long Water Puppet Theater is a representative and useful case to examine. Established in 1969 in Hanoi, Thăng Long Water Puppet Theater is a momentous cultural symbol of Vietnam and is considered the home of divergent traditional puppetries (Nguyễn, 2019). The outstanding dedication to preserving, developing, promoting and performing water puppet shows has diligently cemented its reputable position and significant influence. Most notably, Thăng Long has played an indispensable role in the growth of Vietnamese water puppetry and in reshaping traditional spiritual customs into a modified form of musical performance that appeals to contemporary tastes and modern social contexts: “many aspects of this performance, from the puppets that spray water toward the viewers to the singing fairies, are found in contemporary presentations” (Foley, 2001). In Thăng Long, each one-hour performance has ticket prices ranging from 100,000 to 200,000 VND (approximately €4 to €8) depending on the seat position. There are five to seven shifts a day to meet the huge demands of local audiences and foreign tourists.

How do water puppets work?

Higgins & Higgins (2001) discover intermediality “in the theater and in the visual arts, the happening, and certain varieties of physical constructions”. Similarly, water puppet shows in Thăng Long transcend formal boundaries, fusing and blending sculptural craftsmanship, puppetry, music and storytelling. A complete water puppet show cannot lack any of these supporting elements.

First there is sculptural craftsmanship. The puppet itself is an elaborate and meticulously sculpted art product that is born from the hands of the artisans. To make a complete puppet, there are different stages to go through: cutting the wood, chiseling and shaping, smoothing, painting, decorating and eventually assembling the body and the base of the puppet. The woody puppets are covered with outer layers of paint and varnish that prevent them from being injured, warped or waterlogged. Nguyễn Văn Phi - a water puppetry artist in the Dong Anh district of Hanoi shared: “the puppets are made manually by human hands so they will be either round or distorted, there is no perfection that aligns to any framework. Each puppet, even though it is the same character, still has a different look and spirit.” (Nguyễn, 2019).

Display of Water Puppetry sculptures

Water puppet artist Nguyễn Văn Phi in his making of the farmer character

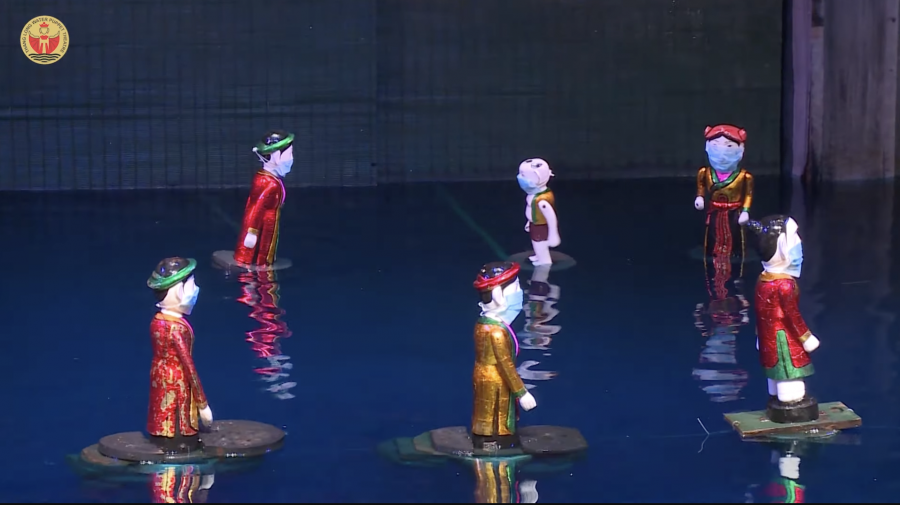

Water puppets always have two inseparable parts, namely the body and the base. The body floats above the water to represent the character. The base sinks under the water to keep the puppet afloat and is the place where the machine is installed to control the puppet's movements. There are three different artist roles in water puppetry: the puppeteers, the instrumentalists and the vocalists. While the puppeteers stay behind the stage's curtain, the instrumentalists and the vocalists are set on the left and right onshore sides of the stage to perform. They provide voiceovers for each puppet's movements and interact with the audience.

Thuỷ Đình stage

The puppeteers, immerse themselves in the simulated lake of the stage, with the water level being about thigh-high to control the puppets. The controlling techniques are trained as esoteric skills depending on which master and school the puppeteer follows (Khê & Wehle, 1985).

Backstage where the puppeteers control the show

There are three general ways to control the puppets. For smaller puppets, the method is to fasten them to the end of bamboo poles and to maneuver them around the water. Bigger puppets require a large circular disc used as a flotation base. More complicated puppets such as a dragon will use a combination of the first two and can include the incorporation of a rudder to make the movements easier. The water is somewhat murky and typically dyed in blue or dark green to conceal the puppet’s actual moving techniques, thereby creating the illusion that the puppets move by themselves: “pole-manipulated figures are more flexible and can pop from under the surface at any spot in front of the stage house, emerging magically from the murky water at the precise site the manipulator selects.” (Foley, 2001)

Drawing of puppet mechanism

The stories

The topics of the stories that are told with water puppets are quite diverse, reflecting different aspects of Vietnamese lifestyle, culture and people. Just like in a cinema, audiences will choose which story they want to buy the ticket for. There are 5 main topics:

1. Reflecting agricultural works through folk poetry

Water puppet characters are built in agricultural symbols such as farmer, buffalo, fish, and duck to show agricultural works such as plowing, herding, hunting, fishing, grinding rice or pounding wheat.

“Let me tell you about the rice fields, the villages, enclosed in emerald green bamboo,

The sound of a flute floating above the back of a buffalo la-a-a

Come back those who miss the homeland.”

A translated poem excerpt from a water puppet show (Foley, 2001)

2. Presenting religious activities

Recreational enterprises and folk games such as boat racing, wrestling, dragon dancing, flagging and prayer activities are reproduced through interactive scenarios.

3. Celebrating historical figures

Milestones in the lives of national heroes are highlighted, especially those in the long Vietnam War.

4. Expressing spiritual beliefs through folk tales

Fairy tales are vividly retold on the water's surface.

5. The breath of the present

Especially in recent years, water puppetry has also touched on more contemporary topics such as COVID-19, corruption, and Vietnam's sovereignty over sea and islands, thereby voicing satirical criticism.

My village during Covid

Water puppetry as an example of intermediality

The harmonized fusion between sculptural craftsmanship, puppetry, music, poetry and storytelling not only shows the artistic value of water puppetry but also illustrates why it can be seen as an example of intermediality.

In addition, by actualizing and illustrating the folk tales and poems, religious beliefs and historical narratives of the past(Nhà hát Múa rối Thăng Long, 2021), water puppetry demonstrates a characteristic of intermediality that “in intermedia, the visual element is fused conceptually with the words” (Higgins & Higgins, 2001). As Pack, Eblin, & Walther (2012) indicate, “the connections between Vietnamese Water Puppetry and important aspects of religion and spirituality in northern Vietnam have manifested over the centuries in various components and dimensions of the water puppetry performance”. Just like Higgins & Higgins (2001) find intermediality in the example of “visual poetry” from Jean-François Bory or in Duane Michaels’ work, we see similar - albeit different - "visual folk tales", “visual historical narratives” and “visual religious beliefs” in water puppetry.

The ancient red tile-roofed of the olden village halls are visualized on the stage

Higgins & Higgins (2001) also suggest that the “medium” in intermediality constitutes a fusion between “art” and “not art”. This notion can also be found in the unique stage of the water puppet shows. Unlike other types of puppetry that can be shown in flexible spaces, the performance environment of water puppetry requires an association with a special stage structure called “Thuỷ Đình”, with “Thuỷ” standing for “Water” and “Đình” standing for “Village Hall”. The stage name is so because it recreates and illustrates the village hall where water puppetry was first born. The esteemed artist Quốc Vũ - Deputy Director at Thăng Long Water Puppet Theater - expressed: “in folklore, for the convenience of worshipping the water god, the village halls were often placed near watery areas. Thus, the shallow pond, lake or canal became the stage of water puppetry" (Nguyễn, 2019). In Thăng Long theater, the ancient red tile-roof of the olden village halls are visualized on the simulated lake and this inseparable combination creates the uniqueness of Thuỷ Đình - the water stage; the ‘art’ and ‘not art’.

“Even as a foreign spectator, the general idea of the story often transcends the language barrier because the interaction between the puppet characters and mood created by the music is easily interpreted.” (Foley, 2001)

The musical accompaniment to water puppet performances acts as a medium for telling the story (Prateepchuang, Leauboonshoo, & Thang, 2016). In the past, water puppets only performed traditional praying dances in the background of musical instruments without singing or adding dialogue. As the vocalist art developed in Vietnam, folk tunes, narrative expression and satirical lines gradually appeared in water puppetry. Since then, at Thang Long theater, music in water puppetry is characterized by the special composition of folk tunes to breathe spirit into every motion of the inanimate puppets. The musical decoration is delivered by “an orchestra consisting of a zither (đàn tranh), a bowed string instrument (đàn nhị), a lute (đàn nguyệt), flutes (sáo), drums (trống), a wooden bell (mỏ), clappers (phách), and a gong (thanh la), all accompanying the singer who takes lyrics from the folk poem” (Foley, 2001). In water puppetry, music speaks its language to close the linguistic gaps among audiences and performers: “even as a foreign spectator, the general idea of the story often transcends the language barrier because the interaction between the puppet characters and mood created by the music is easily interpreted.” (Foley, 2001)

Live orchestras play music on either side of the stage

Multimediality is often related to the domain of theater because various media forms are blended, and visual, auditory, and interactive elements are combined to create a single, coherent production (Klement, Chráska, Dostál, & Marešová, 2015). In order to bring the most authentic and complete experience to the audience, and to give spectators the feeling that they find themselves in a Vietnamese village of a few centuries ago, a special lighting system is invented to reflect into the water, highlighting the shadows, colors and spirit of the puppets. Water puppetry is a feast of the senses in which the audience can watch the puppet movements, hear the special musical composition, see the magical visual reflections and contemplate about the ancient stories.

“Thank you”

Closing reflections

This article has argued for the thesis that water puppetry can be seen as an example of intermediality and multimediality. As a must-see attraction of Vietnamese tourism (Nhà hát Múa rối Thăng Long, 2021), water puppetry is a symbol of national pride and a recommendation for all the foreign visitors who are interested in exploring Vietnamese culture.

Let's take a virtual tour here!

References

Foley, K. (2001). The metonymy of art: Vietnamese water puppetry as a representation of modern Vietnam. TDR/The Drama Review, 45(4), 129-141.

Gaboriault, D. (2009). Vietnamese water puppet theater: A look through the ages. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1209&context=...

Higgins, D., & Higgins, H. (2001). Intermedia. Leonardo, 34(1), 49-54.

Khê, T. V., & Wehle, P. (1985). Vietnamese Water Puppets. Performing Arts Journal, 9(1), 73-82. Retrieved from https://www-jstor-org.tilburguniversity.idm.oclc.org/stable/pdf/3245454....

Klement, M., CHRÁSKA, M., DOSTÁL, J., & MAREŠOVÁ, H. (2015). Multimediality and interactivity: Traditional and contemporary perception. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 11, 414-422.

Nguyễn, C. (2019). Rối Nước đào thục: Chúng tôi tự phong "nghệ nhân" Cho Nhau. Quân Đội Nhân Dân. Retrieved from http://hanoi.qdnd.vn/van-hoa-the-thao/roi-nuoc-dao-thuc-chung-toi-tu-pho...

Nhà hát Múa rối Thăng Long. (2021). Vietnam Water Puppet art - Thang Long Water Puppet Theater [Video]. YouTube. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-bezb1tRCZM

Pack, S., Eblin, M., & Walther, C. (2012). Water puppetry in the red river Delta and beyond: tourism and the commodification of an ancient tradition. ASIANetwork Exchange A Journal for Asian Studies in the Liberal Arts, 19(2).

Phạm, H. N. (2023). "Giữ lửa" Nghệ Thuật Rối Nước. Đại đoàn kết. Retrieved from http://daidoanket.vn/giu-lua-nghe-thuat-roi-nuoc-5713957.html

Prateepchuang, S., Leauboonshoo, S., & Thang, T. N. (2016). The musical heritage of water puppet performance in Hanoi, Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Wacana Seni Journal of Arts Discourse, 15, 95–112. http://dx.doi.org/10.21315/ws2016.15.4

Thang Long Water Puppet Theater. (n.d.). Images Library - Shows Year 2020. Retrieved from https://thanglongwaterpuppet.com/images-library