What is 'Live Facial Recognition' and how dangerous is it?

The world is becoming a more and more globalised. People are able to move freely and do things our ancestors would not have thought possible. Technology is also evolving in a way that makes it possible to support law officers whenever they need it. One of these emerging technologies is live facial recognition. It enables police enforcement agencies to locate or identify crime suspects by scanning millions of faces in cities or crowds.

All new technologies raise concerns about privacy, and live facial recognition is no exception. In this article, I will explain what live facial recognition technology is, how it is affecting our privacy, and the possible dangers for society.

Live Facial Recognition

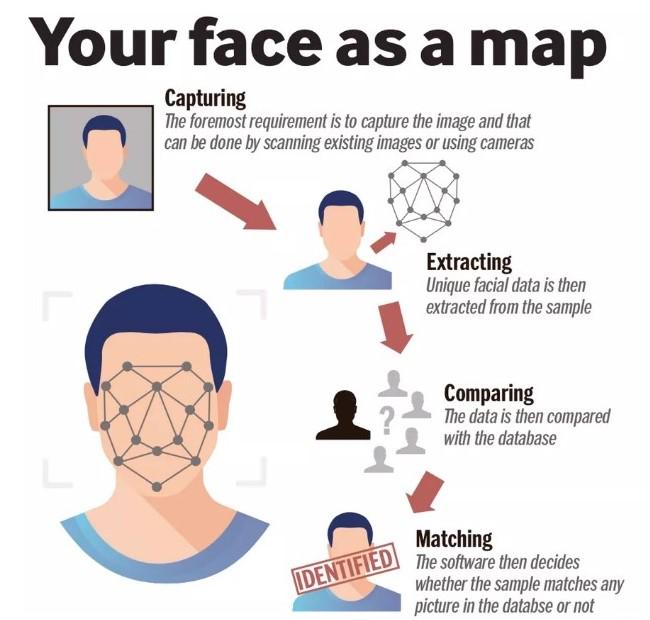

In Automated Facial recognition technology: recent developments and approaches to oversight, Mann and Smith explain that automated or live facial recognition is "an extension of facial ‘profiling’ or ‘mapping’ that has been used in criminal justice systems around the world since the 19th century and continues to be used today” (2017, p. 122). In a traditional sense, forensic facial mapping involves comparing measurements between facial features or similarities and differences in facial features. Facial recognition technology therefore works with “the automated extraction, digitalisation, and comparison of the spatial and geometric distribution of facial features” (p. 122). Using algorithms, faces are detected in images and compared with those stored in databases or watchlists, which can include suspects, missing people, and persons of interest (figure 1). In comparison to other forms of biometrics such as DNA and fingerprints, live facial recognition is less invasive and can be performed from a distance, or even possibly integrated into existing surveillance systems such as CCTV.

Figure 1: Live Facial Recognition Process

Anglim et al. explain that facial recognition technologies “are able to perform several functions, including (1) detecting a face in an image; (2) estimating personal characteristics, such as an individual’s age, race, or gender; (3) verifying identity by accepting or denying the identity claimed by a person; and (4) identifying an individual by matching an image of an unknown person to a gallery of known people" (2016, p. 190). Studies show that the involved algorithms have been improved over time. Therefore error rates continue to decline, and identification of individuals from poor quality images is improving. Facial recognition technology systems can identify two different kinds of errors, namely false positives, which are reporting an incorrect match, or false negatives, which are not reporting a match when one exists (Anglim et al, 2016).

The use of social media websites such as Facebook and Instagram have contributed to a rapid growth of photo and video content.

The question of how law enforcement agencies fill their databases with facial templates and images is easily answered. The use of social media websites such as Facebook and Instagram have contributed to a rapid growth of photo and video content. It is estimated that approximately 6 billion photos are uploaded to Facebook every month (Mann & Smith, 2017). Facebook even has its own facial recognition technology system, which “automatically tags photographs with the identity of the people in them, linking their images to personal details they provide on their own page, including age, gender, location, contacts and political views” (p. 124).

Who is using this technology so far? In China it is used to spot and fine jaywalkers or verify students at school gates, whereas in Israel it is used to covertly track Palestinians (Sample, 2019). In the US and in Russia it is used in major cities along with CCTV. In Europe however, it is mainly being used on a trial basis. For example in Britain, law enforcement agencies have used facial recognition technology software on city streets, music festivals, and football and rugby crowds.

Opportunities and Problems

Facial recognition software is not only present on the streets in the form of CCTV cameras. Apple consumers come across the technology when unlocking their more recent phones. With the blink of an eye, they cannot only unlock their device, but also pay bills, confirm purchases and perform many other transactions. Even video doorbells can recognise visitors when a photo of them has been previously uploaded (Sample, 2019). We already enjoy other opportunities introduced by live facial recognition technology, for example at the airport: with a biometric passport, all one has to do is look into a camera and the barrier opens. This allows passengers to save time instead of waiting in long lines for border security personnel to check their passports individually. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security predicts that it will be used on 97 percent of travellers by 2023 (Marr, 2019). These are perfect examples of where facial recognition technology is already being included - and accepted - in our everyday lives.

If recorded, identified, and analysed at the same time, it is almost impossible to control who has which information about whom.

In the streets, live facial recognition can improve public security significantly. It can automatically find and identify suspects, who can then be stopped and checked by the police or other security agencies. This reduces innocent bystanders being stopped, checked, or searched without motive or proper reasoning. Anglim et al (2016) mention that controlled tests indicated that “facial recognition algorithms surpassed humans in accurately identifying whether pairs of face images, taken under different lighting, were images of the same person or different people” (p. 190). This technology can also help find missing children and seniors in big cities and crowds. Times of India (2018) reported that when the software was trialled in Delhi to help find missing children, almost 3.000 children could be identified in four days.

Although live facial recognition has its benefits, it also has its disadvantages. One prominent problem is the increased risk of decisions and outcomes that are biased and, in some cases, in violation of laws prohibiting discrimination (Smith, 2018). While algorithms are performing better and better, the ACLU Massachusetts (2020) points out that “numerous studies have shown that face surveillance technologies are racially biased, particularly against Black women.” They refer to an MIT study that found that “Black women were 35% more likely than white men to be misclassified,” and the algorithm even failed to identify the faces of Oprah Winfrey, Michelle Obama, and Serena Williams. Most face detection algorithms are trained on datasets that overwhelmingly contain white men and are then used on datasets that often disproportionately contain Black men, which could be one of the main underlying factors in gender and racial bias (ACLU Massachusetts, 2020).

Surveillance with live facial recognition technology gives governments unlimited and unforeseen power to track every movement a person makes.

Furthermore, the use of live facial recognition can lead to new intrusions upon people’s privacy. Without regulations, every public establishment could install cameras connected to live facial recognition technologies. Identifying shoplifters is certainly a step forward, but in doing so everyone else is also identified and registered. People may argue that it is fine to be identified and watched because they have nothing to hide. But as Kade Crockford (2019) points out, “privacy is not secrecy, it is control.” In her TED talk the privacy advocate explains that some information is private, for example medical records, and is therefore not secret, since the information is shared with trusted people. If information is recorded, identified, and analysed at the same time, it is almost impossible to control who has which information about whom.

Figure 2: Face surveillance

Another problem humanity faces with live facial recognition technology is its use for mass surveillance, which can encroach on democratic freedoms and human rights. As Smith (2018) explains, “democracy has always depended on the ability of people to assemble, to meet and talk with each other and even to discuss their views both in private and in public. This in turn relies on the ability of people to move freely and without constant government surveillance." When combined with omnipresent cameras, massive computing power, and storage in the cloud, facial recognition technology could allow governments to enable continuous surveillance (Smith 2018). People can be tracked anywhere, anytime, or even all the time. Going a step further, a governments can then record peoples’ movements, habits, and associations (Crockford, 2019). Figure 2, above, shows what this surveillance could look like.

Privacy

How does the proliferation of facial recognition technology impact our privacy? The issue of privacy is vital to explicating the possibly dangerous nature of live facial recognition technology. Lyon (2015) explains that “privacy is often seen as having a number of dimensions: the choice to be let alone – ‘unhindered’, that is – limiting others’ access to the self, and rights to secrecy, control of personal information, personhood and intimacy” (pp. 93-94). Surveillance with live facial recognition technology gives governments unlimited and unforeseen power to track every movement a person makes (ACLU Massachusetts, 2020). Therefore, citizens do not have the choice to be let alone: every movement can be watched, tracked, and accessed again and again. According to boyd (2010), we have moved into an era of “public by default, private through effort.” This means that information is generally publicly accessible, whereas keeping information private and away from the public eye takes effort. An expression that has been used to describe online contexts would then, with the widespread use of facial recognition, be applicable to everyday life, online and offline.

Being watched at all times does not only affect one's sense of privacy, but also, according to Brincker (2017), our behaviour: “pervasive surveillance and disciplinary structures erode individuality, creativity, innovation and dissent and thus overall impede organic and democratic change" (p. 77). In most surveyed environments people are unsure what to do, but most often react in one of three ways: denial, submission, or paralysis. Brincker (2017) explains that “in many contexts, we ignore the accessibility to unknown others and hope that it will be inconsequential, even when we to some extent know that this is unlikely" (p. 87). Live facial recognition could, therefore, change how we behave and who we are, pressuring citizens into submission or even paralysis to the point of citizens not wanting to leave the house anymore.

A democratic society depends on people being able to move freely and associate, and talk with whomever they want.

As stated by Mann and Smith (2017), the main privacy concerns associated with live facial recognition technology “relate to the circumstances in which biometric information is obtained, retained, stored, shared between agencies, and the overall purposes for which it is used by governments, law enforcement and security agencies” (p. 130). The fact that we are seen and recorded at all times seems to move out of the spotlight. The Intercept (2020) reported that leaked European Union documents show that countries could soon be sharing individual national police facial recognition databases with not only other EU countries but also with the United States. This could create “a massive transatlantic consolidation of biometric data” (Campbell & Jones, 2020), leading to citizens being surveyed anywhere, anytime in participating countries. What may be an improvement for general police work could also become an issue of surveillance for all the wrong reasons.

The advocacy director for Privacy International, Edin Omanovic, “worries about a pan-European face database being used for ‘politically motivated surveillance’” (Campbell & Jones, 2020). The potential for ‘function creep’, where information taken for a particular purpose is used for other purposes without consent (Mann & Smith, 2017), and ‘data creep’, which occurs when information is shared with third parties without authorisation and then aggregated with other data (Anglim et al, 2016), is immense. This saving, sharing, and analysing of data with unauthorised people can put our fundamental freedoms at risk. As mentioned above, a democratic society depends on people being able to move freely and associate and talk with whomever they want. Without this freedom, citizens would not be able to protest, go to AA meetings, or participate in women's or Black Lives Matter marches.

In fact, the recently resurfaced Black Lives Matter movement and protests against police brutality have sparked a new wave of dissent against the use of live facial recognition technology by law enforcement agencies. In order to push the US government to regulate its use, big tech companies like IBM, Amazon, and Microsoft have committed to temporarily not selling the technology to law enforcement agencies (Moné, 2020). Amazon hopes that its one-year moratorium gives the government enough time to implement appropriate rules (Moné, 2020). Although the companies' announcements to pause sales is a step in the right direction, experts warn that the threat to our privacy will not vanish in a year. Law enforcement agencies who already have unreliable or faulty software can continue to use it (Moné, 2020). These announcements confirm the serious harm already done to Black communities and other minority groups through the unregulated use of facial recognition technology by law enforcement agencies.

Harmless or dangerous

Live facial recognition is most certainly the next step in the future. With its ability to detect a face in an image, estimate personal characteristics, verify identities, and identify unknown individuals, the technology opens many doors in the quest to prosecute criminals. It is also very useful in our everyday lives, where it is used at airports for border security and even in our own phones. With the help of this technology, criminals can be caught more easily and missing people can be identified.

Although live facial recognition technology is promising, we have to keep a close eye on the prevalent disadvantages in its use. Algorithms’ gender and race biases support discriminatory ways of handling crime and injustice that our society was working on leaving behind. Additionally, millions of innocent citizens are mass surveyed and movements and associations are recorded, stored, processed, and analysed, which can have a significant impact on our democratic freedoms and human rights. Both of these concerns have resulted in the current sales pause by major tech companies. Finally, we have to pay attention to the trans-institutional flow of data. With the EU planning to share their biometric data sets with the US, new opportunities to misuse the technology emerge.

All in all, live facial recognition may not only be useful to law enforcement agencies but also to our society. We must ensure that the technology works without any kind of bias and does not encroach on our democratic freedoms, human rights, or privacy in any way. With the right amount of regulation, the technology is set to transform our lives in many ways.

References

ACLU Massachusetts. (2020). Press Pause on Face Surveillance.

Anglim, C. et al. (2016). Privacy Rights in the Digital Age. Grey House Publishing. ProQuest Ebook Central.

boyd, d. (2010). "Privacy, Publicity, and Visibility". Microsoft Tech Festival. Redmond.

Brincker, M. (2017). Privacy in public and the contextual conditions of agency. In T. Timan, B.C. Newell, & B. J. Koops (Eds.), Privacy in Public Space: Conceptual and Regulatory Challenges (pp. 64- 90). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Campbell, Z., & Jones, C. (2020). Leaked Reports Show EU Police Are Planning a Pan-European Network of Facial Recognition Databases. The Intercept.

Crockford, K. (2019). What you need to know about face surveillance. TEDxCambridgeSalon.

Delhi: Facial recognition system helps trace 3,000 missing children in 4 days. (2018). Times of India.

Lyon, D. (2015). Surveillance after Snowden. Cambridge: Polity.

Mann, M., & Smith, M. (2017). Automated facial recognition technology: Recent developments and approaches to oversight. University of New South Wales Law Journal, 40(1), 121-145.

Marr, B. (2019). Facial Recognition Technology: Here Are The Important Pros And Cons. Forbes.

Moné, B. (2020). Outrage over police brutality has finally convinced Amazon, Microsoft, and IBM to rule out selling facial recognition tech to law enforcement. Business Insider.

Sample, I. (2019). What is facial recognition - and how sinister is it?. The Guardian.

Smith, B. (2018). Facial recognition: It's time for action.