Black Pete: When commodifying “blackness” is tradition

Every year when the trees shed their leaves, I like to show my opposition to the Dutch folklore of Black Pete. The annual celebration of Saint Nicholas and his black faced servant makes me ashamed of my home country, and I make it known in any way I can. I’m often met with disagreement and heated discussions. I got especially emotional when my own grandmother, after seeing my anti-Black Pete propaganda, protested that Black Pete is “tradition,” and moreover one she looks back on with lots of nostalgia. Thus, he should remain…right?

Admittedly, sympathizers usually make this argument. It seems like a huge threat: their tradition is being taken from them, the Netherlands is changing for the worse! In this article I briefly discuss the unavoidable and ever-changing nature of our traditions, as well as exploring how this tradition is ingrained in a deeper structure of white dominance.

Black Pete, a typical Dutch tradition

Originating with Eric Hobsbawm, the term “invented tradition” refers to “a set of practices, normally governed by overtly or tacitly accepted rules and of a ritual or symbolic nature, which seek to inculcate certain values and norms of behavior by repetition which automatically implies continuity with the past” (Post, 1996, p. 93). Post (1996, p. 87) highlights Hobsbawm's interest in the process of nation formation and urges his readers to keep this context in mind when dealing with the concept of tradition invention. Looking at the Dutch St. Nicholas, and with him Black Pete, the festivity is absolutely such an invented tradition.

For instance, we have certain acknowledged certain “rules” regarding how Black Pete and his boss should look and annual rituals like the arrival of the steamboat, the scattering of candy and giving gifts. These rituals didn’t appear out of nowhere, they were constructed and repeated. In this way the Dutch now have an unspoken “common sense” understanding of their national holiday. In the Black Pete debate, it is generally argued that these traditions are quintessentially Dutch. Our prime minister, Mark Rutte, even said that Black Pete is black because that’s just the way it has always been (Van der Pijl & Goulordava 2014). Is this in fact the case?

Annual St. Nicholas parade (2018, Groningen)

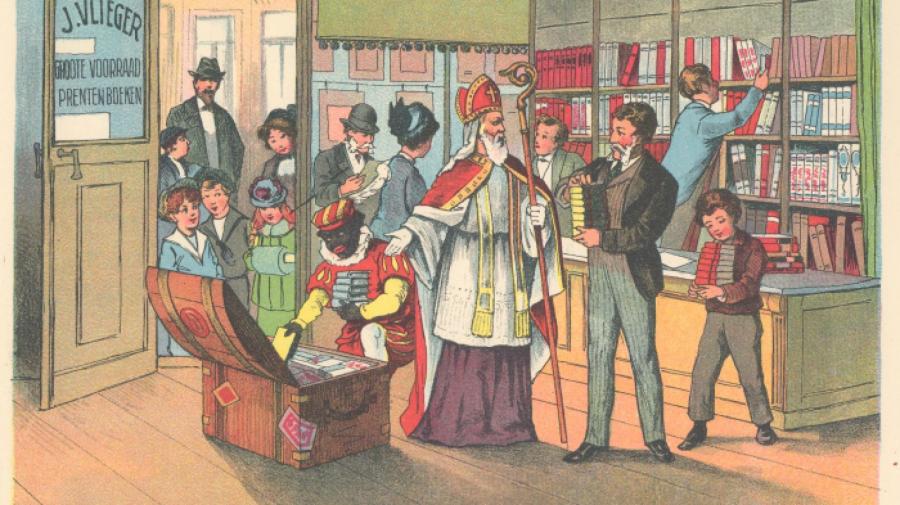

The image of black man as St. Nicholas' helper was especially popularized by booklets published in the 1850s by an educator named Jan Schenkman. Before this, St. Nicholas and Black Pete were actually one blackened bogeyman who resembled a devil and wore chains, a mask, and a broom while rounding up naughty children. Only later were they split up into a bishop-like figure and a (initially white) helper. Black Pete and St Nicholas as we now know them are based on this folklore and subsequently Schenkman's books. All of this is very much in line with Hobsbawm's idea of innovation of material from the past, which leads to the invention of tradition (done massively in the 19th century) by ritualization and repetition (Post, 1996, p. 91).

Schenkman's booklet featuring Black Pete

Tradition transitions

Whereas Hobsbawm's interpretation of tradition is quite fixed, Post (1996) deems it very much subject to change. Change is constantly in conflict with the continuity of tradition (and thus with stability), yet eventually pushes tradition into adaptation and compromise. Post furthermore argues that this adaption process is also "invented tradition.” Although my grandmother might not be aware, “my” Black Pete is already very much different from hers and hers from the generations before her, not so much in appearance but in his role.

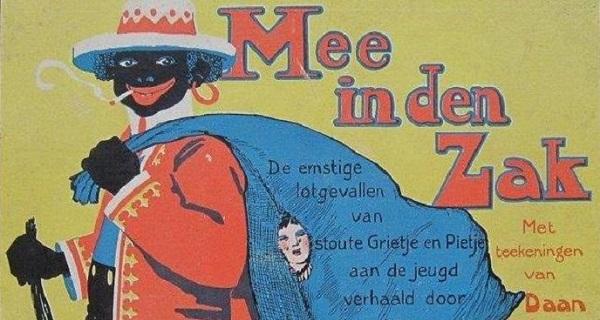

Pete used to be a frightening servant that would spank you and kidnap you to Spain in his burlap sack if you were naughty. In pedagogical circles this was (rightly) deemed traumatic for children, so Black Pete slowly changed to a loveable friend and helper instead. However this wasn’t until nearly the end of the 20th century. Furthermore, while his skin color and duty as a helper were determined in 1850, Black Pete's demeanor didn't change until around 1950. These are just a few of many examples of how tradition adapts.

A 1915s children's book's (Title: "Along in the sack") Black Pete, sporting his burlap sack

Understanding these adjustments is vital. Why, Post wonders, do traditions change? I argue that an important aspect is the support of a current social agenda - for example, the aforementioned pedagogic one. I expect it's not a coincidence that Schenkman published his booklets depicting a black helper in 1850. Social agendas and cultural utterances such as Schenkman's work should be put in their historical contexts. Indeed, Black Pete's emergence in 1850 is smack in the middle of the Netherlands' process of abolishing slavery. The Dutch signed a treaty condeming slavery in 1814 and began officially abolishing it in 1863 (Canon van Nederland, n.d.).

In Schenkman's booklets, the black man is not only depicted as the white man's servant, he is also shown as simple or evil and frightening. Such themes surely arose in European circles around these times. One can thus argue that these booklets and their respective characters reflect this distinct era in the history of slavery. It should further be highlighted that the central function of tradition is the creation of social, religious and political identities (Post, 1996, p. 99). The Netherlands has changed since 1850, we are far more multicultural and home to far more black people, largely due to our colonial past. Hence, our identity as a nation is different now. The current celebration of St. Nicholas doesn’t fit this.

Black as a commodity

When speaking on both slavery and the formation of identity, I can’t help but think of Hills-Collins (1990) skillful phrasing of their comparability. She mentions how, akin to the way bodies were bought and sold on the open market, in our commodity consumer culture identity can likewise be purchased. White people moreover seem to have the desire to rebuild their identity by consuming the “exotic other”, or as Hooks (1992) describes, ethnicity becomes a spice used to “liven up” the white, bland mainstream culture (Watts & Orbe 2002).

Blackness is a source of both enjoyment and oppression, pleasure and anxiety

Black people indeed are and have been seen as the “exotic other”, resulting in a sort of “Blackophilia/Blackophobia” dynamic as Yousman (2003) terms it. In other words, we can observe white societal fascination and simultaneous disgust with Blackness. Blackness is a source of both enjoyment and oppression, pleasure and anxiety.

This polarity is specifically well represented in the colonial era and thus the historical backdrop for Black Pete’s creation. Black people were enslaved and perceived as “inferior savages” while also essentialized from black person to a black body. This essentialization is of course present in the literal trading of black bodies but also in systemic rape of black female bodies, often by white males, and the exhibition of Sara Baartman and many other black enslaved people (Van der Pijl & Goulordava, 2014; Magubane, 2001).

The objectification of the (submissive) black body in the name of amusement is not new and one that is mirrored every year in the Netherlands - Van der Pijl & Goulordava

Yousman (2003, 378) discusses the habit of commodifying cultural differences as a source of titillation and pleasure for white consumers. This is exactly the case here. Black bodies are an object of spectacle, essentialized to a source of entertainment and pleasure. Black people are thus also commodified, or like Njee (2016, p. 115) explains “turned into a marketable good that can be bought and sold.” The objectification of the (submissive) black body in the name of amusement is not new and one that is reproduced every year in the Netherlands (Van der Pijl & Goulordava, 2014).

“Our” Black Pete is in fact a fine example of black commodification: a black person is reduced to a black body and furthermore simplified to “parts” (e.g., skin color, afro hair, big red lips, earrings, etc.) to be an annual spectacle for the non-black Dutch population. He is a caricature of blackness used to sell other goods every November and December. In short, the usage of the black body by whites for consumption, enjoyment, and commerce dates back to slavery (Van der Pijl & Goulordava, 2014). And just like in the trade of black people, Njee (2016, 126) argues that blackness as commodity “can be possessed, owned, controlled and shaped by the consumer.” We can therefore say that our tradition, commodification in the hands of whites, builds upon another Dutch “tradition”: the exploitation of black bodies for consumption by a white supremacist society.

Russell Brand refers to the Dutch tradition as "a colonial hangover" ("Zwart als Roet"/"Black as Soot")

Towards change?

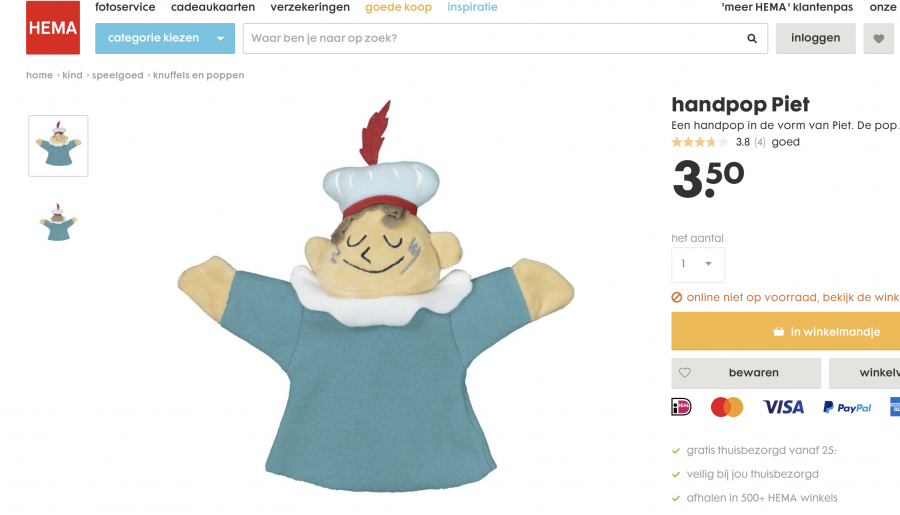

Mainstream discourse about Black Pete has been slowly changing over the years, mostly as a result of the hard work of organizations like Kick out Black Pete. Influential Dutch players have for instance set aside the black caricature in favor of a more inclusive and less racialized version, like the soot-faced Petes that grace the shelves of HEMA and the RTL TV channel. The latter is especially important since it broadcasts the yearly, well-liked show De Club van Sinterklaas (“St. Nicholas’ Club”). In similar fashion, an increasing number of cities are removing Black Pete from their yearly St. Nicholas parades.

An example of HEMA's soot-faced Pete

Even the aforementioned Dutch Prime Minister, Mark Rutte, has seemingly changed his mind about the tradition. In a debate surrounding last year's Black Lives Matter protests, he made clear that his former stand on Pete's blackness has changed out of compassion for the discrimination related to the racial caricature. While he now acknowledges and approves of the need for change in the tradition, he does not think this should be imposed by the government. Instead, he says this should be up to the people, and he feels confident change will eventually come.

This reflects Rutte’s tendency to not be too bold as a leader. Moreover he does not want to admit to the presence of institutional and deeply entrenched racism in The Netherlands. The reason for this? He does not want to antagonize “well-meaning Dutch citizens who would maybe feel that they are called racist." While Post (1996), in contrast to Rutte, not only argues that the imagining and reimagining of tradition is, in fact, a political endeavor, it also seems like our prime minister is deeply committed to upholding the façade of “white innocence” entrenched in Dutch society (Wekker 2016).

Conclusion

All in all, there is a need to acknowledge how deeply drenched our society is in racist ideology inherited from our colonial past. These well-established colonial systems have not only determined the distribution of societal power but also laid the groundwork for traditions such as Black Pete - traditions that, as mentioned, encompass the commodification of blackness. The rigidity of these old systems is now being encountered as more people rally against the caricature of Black Pete and the tradition is slowly pushed to change. I believe the aforementioned tension between continuity and change is felt ever so severely now. I would like to give a tip to people resisting this change: while tradition is powerful, take note from Darwin: the species (or, tradition) that survives is the one that adapts.

References

Hills-Collins, P. (1990). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empowerment. Routledge.

Hooks, B. (1992). Eating the other: Desire and resistance. In Bell Hooks, Black looks: Race and representation (pp. 21-39). South End Press.

Magubane, Z. (2001). Which bodies matter? Feminism, poststructuralism, race and the curious theoretical odyssey of the “Hottentot Venus.” Gender and Society, 15, 816-834.

Njee, N. (2016). Share cropping blackness: White supremacy and the hyper-consumption of black popular culture. McNair Scholars Research Journal, 9(1), 113-133.

Post, P. (1996). Rituals and the functions of the past: Rereading Eric Hobsbawm. Journal of Ritual Studies, 10(2), 91-108.

Van der Pijl, Y. & Goulordava, K. (2014). Black Pete, “Smug Ignorance” and the value of the black body in postcolonial Netherlands. New West Indian Guide/Nieuwe West-Indische Gids, 88(3-4), 262-291.

Watts, E. K. & Orbe, M. (2002). The spectacular consumption of "true" African American culture: "Whassup" with the Budweiser guys? Critical Studies in Media Communcation, 19 (1), 1-20.

Wekker, Gloria (2016). White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race. Duke University Press Books.

Yousman, B. (2003). Blackophilia and blackophobia: White youth, the consumption of rap music, and white supremacy. Communication Theory, 13(4), 366-391