A Brexit in the mind is a Brexit in its consequences

Robin Cohen argues that Brexit has already occurred in the minds and daily lifes.

Brexit and the depressing reality of the Thomas and Thomas theorem

It used to be commonplace – I cannot attest that this remains the case – that sociology students were taught the 1928 Thomas theorem, ‘If men define situations as real, they are real in their consequences’. This statement needs updating and correction, to remove the sexism and to attribute the theorem justly to both authors (Thomas and Thomas, 1928). So the Thomas and Thomas theorem should now read, ‘If people define situations as real, they are real in their consequences’.

What has this got to do with Brexit? I suggest here that journalists, together with their readers and viewers, have become too obsessed with the psychodramas unravelling at Westminster, Brussels and the Supreme Court ruling and need to plug in some sociological antennae. Even if we ignore all the possible outcomes of the EU-UK negotiations (leaving with or without a deal, soft or hard Brexit, long or short extension, revoke, remain or re-join), the corrosive effects predicated by the Thomas and Thomas theorem have already occurred, are continuing, and are likely to persist, whatever the twists and turns of the political dramas unfolding before us.

While the old divisions of class, gender, race and region have far from disappeared, the divisions between Leavers and Remainers have now overlaid them.

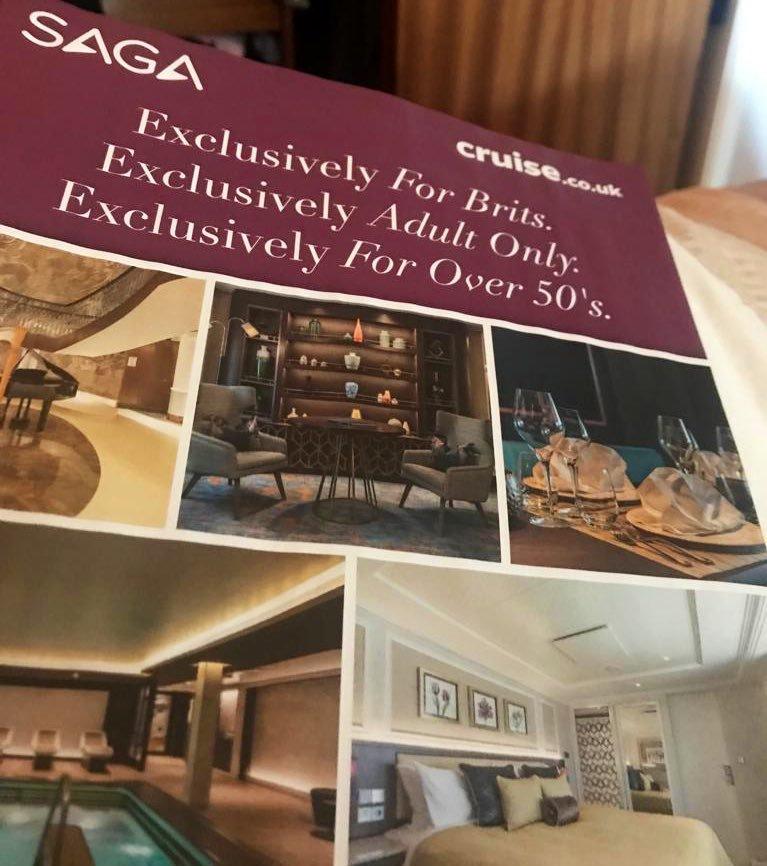

Let me start with two relatively trivial examples that came to my attention as I was drafting this column. The first is news of a brochure issued by cruise.co.uk on behalf of its business partner, Saga, advertising cruises ‘exclusively for Brits’, ‘exclusively adult only’ and ‘exclusively over 50’s’. We can immediately intuit the message – ‘foreigners and young people are not welcome, and you’ll be relieved to learn there will be none on the cruise if you sign up’. Saga disavowed its partner, but the message had already been conveyed, that is, it had become real in its consequences.

The second example is a personal one. My wife returned from her Co-op shop to recount her experience of a very angry woman who had phoned the police with the demand that they remove a beggar ‘who cannot speak English’. On those grounds alone, she asserted, ‘she has no right to be here’. The woman brooked no contradiction.

Brexit as internal border

What both these examples signify is that we should be equally concerned with the internal social borders that are developing in the UK as with the Northern Irish border, the proposed border in the Irish sea or the Dover–Calais crossing. What evidence can be adduced of the salience of ‘internal borders’, or ‘identity frontiers’, beyond a brochure and an anecdote? Take these findings from four reports:

A researcher on hate crimes, Daniel Devine, concluded that his models ‘show that the [Brexit] referendum increased hate crimes by 31 a day, or 638 in a month’, depending on which data were used.

Statistics published by the Nursing and Midwifery Council in May 2019 showed that only 968 European Economic Area nurses and midwives had joined the UK workforce in 2018–19. This was a slight rise from 805 in 2017–18, but it compared with 6,382 in 2016–17 and 9,389 the previous year. Again, 10,000 European nurses had left the NMC register since the 2016 referendum, with more than half saying Brexit was a key reason for their departure.

The corrosive effects predicated by the Thomas and Thomas theorem have already occurred, are continuing, and are likely to persist.

Adriene Yong noted that in the year to June 2017, 5,301 EU citizens were deported from the UK, a 20 per cent rise compared with the previous year, though it is possible the number may be inflated by increased immigration from the EU over that period.

A British Council report published in July 2019, documented the long-term decline in studying European languages and falls since the Brexit referendum. The author of the report also describes a shift in attitude, with some parents saying languages are ‘little use’ as the UK is due to leave the EU. This Brexit effect was particularly notable in secondary schools in poorer areas.

These and similar findings attest to what social psychologists call ‘affective polarization’. Using existing surveys and some original data with a combined total of 18,329 respondents, Hobalt, Leeper and Tilley show that ‘Brexit identities’ (Remainer vs Leaver) are becoming as salient as party (Conservative vs Labour) identities.[vi]Significant percentages of Leavers and Remainers are unhappy at the prospect of their children marrying partners from the ‘other side’ or even talking politics across the Brexit divide. Though the authors hold out the prospect of Brexit identities becoming less important in the future when there is a UK–EU settlement or when another crisis supersedes the Brexit one, they note that to date there has been no weakening of Brexit identities or coming together of the two opposing groups.

Brexit in the digital world

Beyond these studies are other pointers of the salience of the Thomas and Thomas theorem. Activities online, as many observers have suggested, have magnified the echo chamber effect – where participants talk overwhelming to their own side. A study of Facebook posts has confirmed this tendency, though there was a marked difference between Remainers and Leavers. The former conformed to the echo chamber hypothesis, though Leavers were much more inclined to cross-post.

The cross-postings by Brexiters were largely ‘challenger posts’, a polite way of saying they were confrontational.

Is this evidence of more open minds and willingness to engage in a dialogue? Sadly not. The cross-postings by Brexiters were largely ‘challenger posts’, a polite way of saying they were confrontational. At least online, the two camps have effectively separated. For Leavers, Remainers are thought to be arrogant, entitled and unpatriotic while the insults in the opposite direction often describe Leavers as old, angry and ill-educated.

Another intriguing pointer concerns the pub chain J.D. Wetherspoons, the proprietor of which, Tim Martin, appears regularly in the media loudly proclaiming his Leaver credentials and, on the chain’s own web pages, denounces the graduates of Oxford and Cambridge (‘apart from a rebel minority’) for ‘leading the campaign for the surreptitious transfer of power to the unelected oligarchs of Brussels for over 40 years’. Assuming that his potential customer base is separated nearly evenly between Leavers and Remainers, the overt display of his politics (he also donated £200,000 to the Vote Leave campaign) would seem foolhardy. However, Tim Martin’s move is smarter than it may appear. He is setting about defining his customer base quite precisely. By forgoing champagne in favour of New Zealand sparkling wine, providing cheap British beer (served on Brexit beermats) and serving unpretentious food, Martin has created a profitable business with a loyal target market. The Remainer social media campaign to boycott the pub chain is unlikely to have much effect.

Brexit has already happened

While the old divisions of class, gender, race and region have far from disappeared, the divisions between Leavers and Remainers have now overlaid them. Where you live, what you eat and drink, which foreign language you learn (if any), which pub chain you frequent, who you associate with, who you date or marry, where you travel and go on holiday, what public events you attend, what you read online and in print, and a number of other choices of lifestyle and preferences are dividing on Leaver/Remainer lines. In terms of the Thomas and Thomas theorem, Brexit has already happened and has become woven into the warp and woof of our social life

This column was also published on Superdiversity.net

References

William Isaac Thomas and Dorothy Swaine Thomas, The Child in America: Behavior Problems and Programs, New York: Knopf, 1928, pp. 571–72

Sara B. Hobolt, Thomas J. Leeper and James Tilley, ‘Divided by the Vote: Affective Polarization in the Wake of Brexit’.