The Coronavirus and online culture: Lessons we're learning

For scholars in online-offline culture and society, the coronavirus crisis that has been shocking the world since early 2020 will later be seen as a turning point. We are rapidly learning a magnificently detailed set of features of the new online-offline nexus in which we live - features now highlighted by the coronavirus crisis. In what follows, I'll just offer a few quick observations.

In an earlier text on this topic, I already pointed out how the coronavirus crisis highlights some key features of contemporary globalization. We can, in the following remarks, add some more substance to this.

Coronavirus and Offline social distancing

Let me start with a seemingly peripheral but important remark on anachronisms. Much of the vocabulary related to anti-coronavirus measures refers to life in an offline society. The best illustration is the crucial phrase "social distancing": the new rule of physical interpersonal distance to be maintained in social contact, so as to reduce the risk of human-to-human transmission.

One major lesson we are now learning is (a) how deeply integrated our online social resources are in the totality of our social conduct, but (b) how poorly integrated this fact remains in our common vocabulary and worldview.

The term "social" in this phrase is general in use. But in reality, of course, it merely refers to what I said: the offline dimension of social behavior. And, as many many millions of people show, this is just one part of what it is to be "social" these days. Because the void of offline social distancing was, and is, immediately and intensely filled by online tools and practices. People live on and through their smartphones and broadband connections.

And so one very major lesson we are now learning is (a) how deeply integrated our online social resources are in the totality of our social conduct, but (b) how poorly integrated this fact remains in our common vocabulary and worldview: we don't have a word for the hypersociality that kicked in place as soon as offline "social distancing" was imposed.

Online hypersociality

As I said, the reduction of offline social contact led to an ultra-quick and ultra-proficient development of online modes of social interaction. The streets are empty, but our screens are full. Let's start with a straightforward example: 83-year old granny is no longer allowed visitors in her nursing home, but now has access to a tablet through which she can skype with her grandchildren. Millions of people who had never come near online communication tools have become users almost overnight, out of sheer necessity.

Institutions too. Teleworking has become the general practice for all white-collar jobs under conditions of lockdown, and companies have offered crash training courses for staff in how to use Zoom and other teleconferencing tools on a nonstop basis. And yes, even the most traditional institutions have joined in, according to the Times Higher Education:

online university work

Parties or pub-crawls are out of the question now, but collective gaming sessions, collective-but-separate Netflix binging and skype parties are abundantly documented on social media. Social media and other stars are also generously showing us their ways of coping with the lockdown - their methods for staying fit, their new hobbies, the programs they watch, the food they cook, their attempts at hobbywork or art and so forth: all of these are splashed onto Instagram. Vloggers are having a field day, performing artists attract large audiences with living-room concerts on YouTube, compensating for cancelled concerts. Boredom has been turned into intensely shared lifestyle work.

Social media and other stars are also generously showing us their ways of coping with the lockdown.

Network TV appears to have found a new lease of life too, broadcasting some of their greatest hits series from the 1980s and 1990s, and peppering their evening programs with classic blockbuster movies. The lockdown has led to a kind of recycling industry, one can see. But surely, streaming operators such as Netflix must do exceedingly well in these times of obligatory indoors nuclear family entertainment evenings.

Cultural alternatives

It may not look like much, but all of what was just mentioned represents, in actual fact, a reshuffling of the repertoires of cultural genres of mass entertainment. People get re-educated in classic movies (and for the fans, old soccer games turned into highlights and documentaries by lack of actual new games) and they learn the potential for flexibility hidden in what looks like ironclad media formats. One example is the "late night talk show" on US TV. Live recordings of such wildly popular shows are out of the question now. But hosts such as Trevor Noah just provide a surrogate recorded from his kitchen, living room, balcony or bedroom. And god, it's funny.

All of what was just mentioned represents, in actual fact, a reshuffling of the repertoires of cultural genres of mass entertainment.

Live guests in news talkshows are evidently replaced now by long-distance online ones, creating an eerie and Ersatz ambiance to such tightly formatted shows - certainly when skype breaks down. But the thing is: those who wish to remain informed about, for instance, the coronavirus crisis, need to watch these surrogates. And, speaking for myself, the quality is in the content, not in the live studio performace of the guests. It can still be good TV.

Global but local

Lockdown means, in actual practice, that people are under house arrest and thus confined to the strictest possible locality. You are here, and here you stay. But we've already seen that many of us are very much "out there" because of online connections. And that isn't all.

In spite of (or due to) this extreme locality, a number of new global events have taken place. Italian people, locked down in their neighborhood, started joint singing sessions to boost morale, and this format quickly went viral. In several places around the world, similar flashmob-style actions were held to express support for health workers, and these too were widely circulated on the web. On 20 March 2020, over 180 radio stations across Europe simultaneously played "You'll Never Walk Alone" to their audiences. This is - note! - a global radio event, an event using an old media infrastructure addressing the small, intimate circles of home.

The coronavirus crisis has shown us definitively that the big systems of organizing and experiencing everyday social life have changed, and that the online-offline nexus is an inescapable reality.

Needless to say, all of this was accompanied by livestreams, hashtags, TikTok clips, YouTube videos and Instagram testimonials. And a lot of this rapidly spread to other places, as a new format of global social action performed, ironically, from within the strictest local confinement. It spread so widely and so effectively, in fact, that - as Ico Maly recently showed - coronavirus-related things could be algorithmically exploited by political groups to extend and optimize their reach.

Of course, all of this can only happen thanks to the generation of technological tools currently available; fifteen years ago, much of it would have been unthinkable. It's also good to underscore that none of these online tools replaces offline ones, they complement them and provide specific alternatives for otherwise offline social practices (teleworking is an excellent example here). The precise balance between online and offline resources can be understood by trying to imagine a coronavirus crisis with its lockdown, quarantine and spatial isolation effects, in which we would not have access to online resources. And conversely, by trying to imagine a social life entirely led online. Both, undoubtedly, would be judged to be deeply unsatisfactory. They only thrive when they coexist.

So here is the big point. The coronavirus crisis has shown us definitively that the big systems of organizing and experiencing everyday social life have changed, and that the online-offline nexus is an inescapable reality. Much can be done with it, and much is being done with it. But we need to let that reality now saturate our social imagination as well, and adjust our major frames for thinking about contemporary societies accordingly.

It's globalization, folks...

One final remark. It should be self-evident but always merits repeating. The wholesale shift from offline to online social life is a global phenomenon and consequently carries all the features of it - including its structural inequalities. Online infrastructures and tools are not equally distributed across the globe, and not even across a single society.

The more improvement and innovation we see in well-resourced areas, the bigger the inequalities will become between the haves and the have-nots in the field of new technologies.

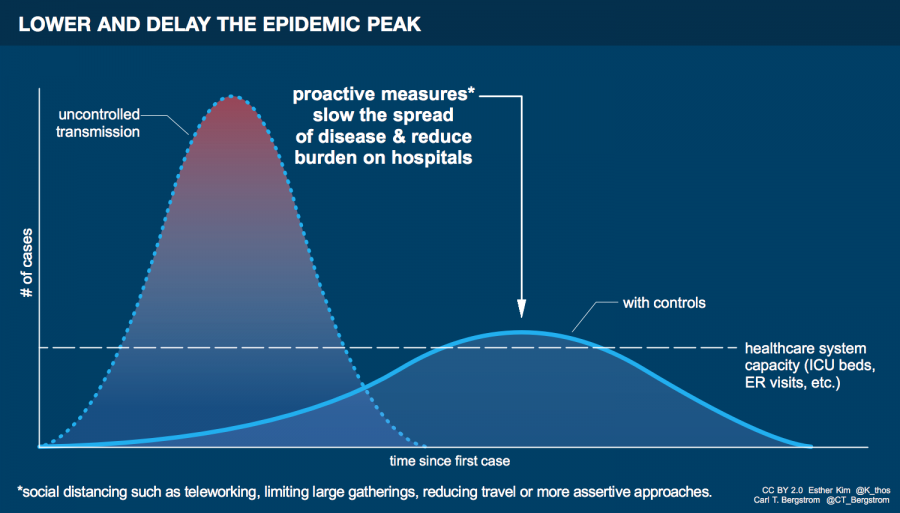

Every aspect of the "hard" coronavirus crisis - its medical and economic dimensions - relies on advanced digital tools. Epidemiology is a science in which big data are crucial, for it is not about the single patient but about very large populations. And interestingly, it is a big data artefact that has become one of the emblematic images of the coronavirus crisis and is turned into a widely used hashtag #flattenthecurve. Here it is.

Slow the curve

The present crisis will undoubtedly yield new and very advanced data-mining and analytical instruments. Evidently, in doing so, the crisis mobilizes the entire spectre of available surveillance and population control technologies, and will contribute to their further development. Even as we speak, authorities and experts are musing over apps capable of tracking one's precise location in the presence of others. The dystopian image of totalized behavioral control monitored and enforced by data-driven online technologies is never really absent from the coronavirus crisis.

And there is more dystopian stuff. In very large regions of the world, such technologies are not available, and the lack of access to them will have severe consequences for people living in such infrastructure-poor regions. The more improvement and innovation we see in well-resourced areas, the bigger the inequalities will become between the haves and the have-nots in the field of new technologies. This, too, risks to be part of the legacy of the cornavirus crisis, and we must be aware of it.